John Dove and Molly White made pop art when the world was in the midst of a cultural revolution. “We were saturated by pop culture and the prevailing wind of change,” the English duo say. This was a time when London sparked with a rare artistic energy that people flocked from all over the world to experience. After they left art school in 1964, punk and pop art took hold: the first record they recognised as punk arrived (“7 and 7 is” by Love) and the pair became “enthralled” with the work of Colin Self, filmmaker Kenneth Anger, and the fashion sensibilities of the Hot Rod kids from California.

These inspirations amalgamated into something wholly original: a multidisciplinary art career that’s still ongoing. “With our very first pieces we were struggling with the meaning of art in a world we were unfamiliar with,” John says. “We produced Dada-esque pieces that questioned what we ourselves were doing. I made The Flying Duck sculptures that were inspired by a Folk Art kitsch classic, but I made it like a 10ft car with a high-tech finish. It was a kind of art anomaly.” Meanwhile, Molly was creating beautiful screen prints that were being stocked at Liberty. “We converged on some screen prints for fabric using photomontage,” he adds. “Suddenly a collection of drawings we had made for tattoos became screen prints on translucent underwear, flesh-coloured T-shirts and stockings. We soon had most of the international fashion business and fashion media knocking at the door.”

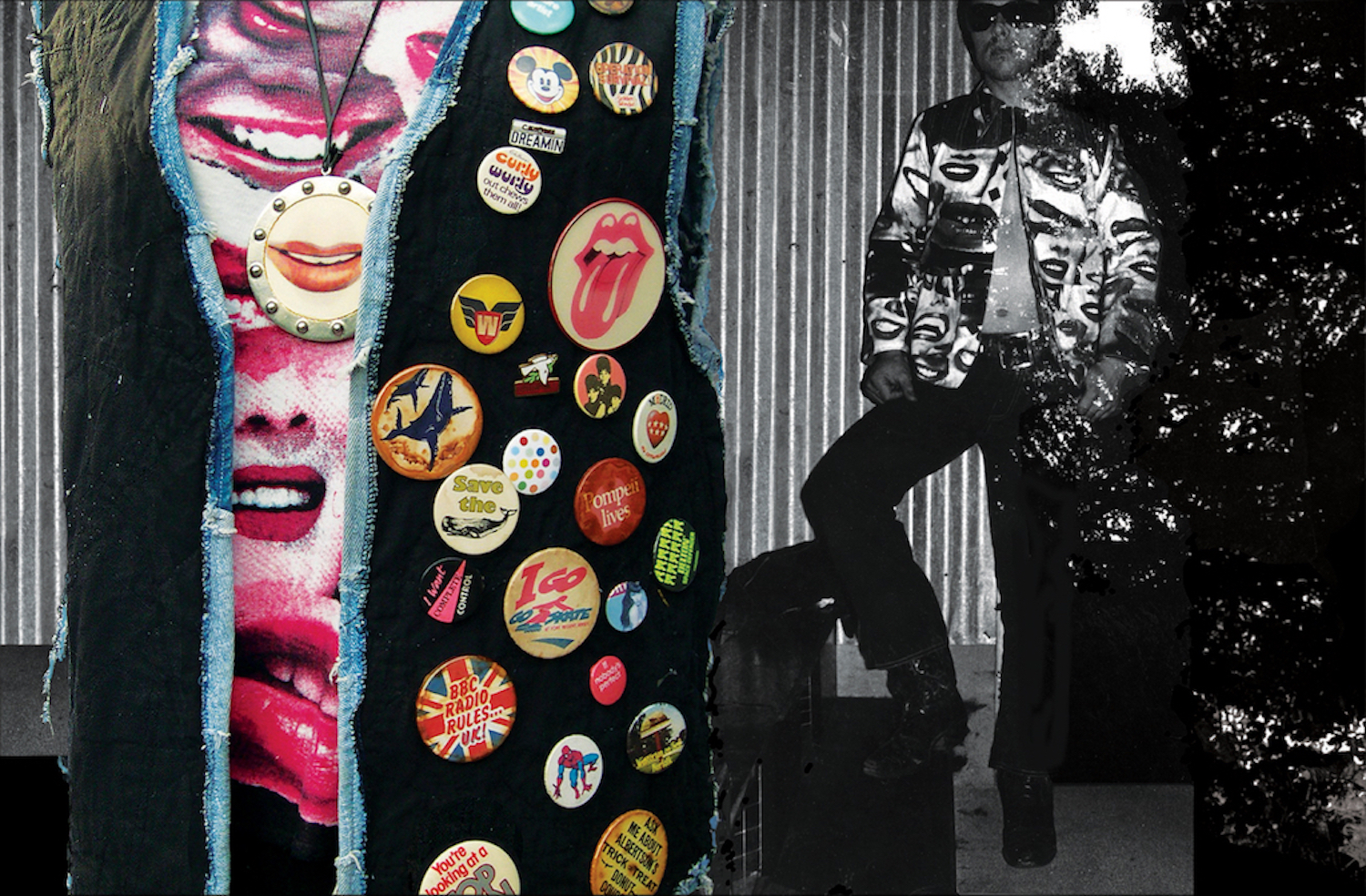

This reputation as creators of elevated pieces of punk fashion made them mainstays in the rock world’s wardrobe — their pieces were regularly seen on Iggy Pop, Debbie Harry and T. Rex’s Marc Bolan. Today, that love for pop art and print still manifests in their sculpture, screenprint and installation work. “Looking back,” they say, “we guess we were engaged in some kind of avant-garde practice creating anomalies of image and style.”

Fifty years on, their work still exudes that same boisterous, sexy, fun and punkish energy that it did when it debuted. It’s no surprise, then, that London skatewear brand Palace have adopted one of their most iconic prints for their new autumn collection.

Using the LIPS print as a key reference point, Palace’s latest lineup of hats, hoodies, fleeces and T-shirts are peppered with the provocative, throwback imagery of John and Molly’s designs. Here, they unpack their wild, illustrious career, the changing face of punk and what it was like to collaborate with Palace.

Your work has been a constant interpretation and championing of subcultures. Does your work exist to channel the same energy of those subcultures?

Philosophy comes later when you’ve made the piece, and you see how it stands up in the world. You say our work has been an interpretation of subcultures through art. I guess we’ve celebrated many rhythms of subcultural movements in the UK and the USA. We often say we were too early for punk, and too late for pop!

We never started anything in the studio through a philosophical concept idea or statement. Your question assumes that creativity is based on something that already exists — this is how the media, the art and design business today resolves things. It’s called synthesis. The internet has made it easier to assess what’s in the universal pot — the variances of theory and ideas. So, synthesis comes up with what can be [considered] the perfect answer. Trouble is, with the input being levelled out by internet search processes and browser systems, eventually the synthesis returns the same answers and the creative flow is in a dry gulch. The energies once created by cultural movements have needed to become subcultural as establishment concepts and precepts prevail.

The energies created by the ongoing subcultural movements in London were running hot and were in the air, so we were integral to it in terms of energy, but not exactly driven by it. We were independent, working at a tangent under our own steam.

LIPS became an important piece for us and formed a key part of the T-shirt collection produced over the following 20 years for Kitsch-22 and later with BOY Blackmail. David LaChapelle photographed Drew Barrymore in the LIPS Jeans as a pull-out poster for Max magazine and a cover for Preview. In 1994 the print was shown at the STREET STYLE exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Paul Stolper loves collaborations with art and design groups on the borderline of the gallery scene. He often writes about the convergence culture and how the visual language crosses the lines of ‘Pop Art’ and ‘Popular Art’.

What modus operandi or practices have you stuck to throughout your careers?

We’ve never consciously had a modus operandi but we’ve probably travelled on roads that were laid down at an early stage of our working life. Our screen printing table has been the centre of attraction for us and has been our work comfort zone. It always occupies the largest prime space we have. When we make sculptures and paintings, they usually end up on the print table, too, even though there’s nothing to print. We’ve become so familiar with it and all the stuff associated with its operation, it’s like a magical third arm that comes up with all the answers. Talking about style and content, they are parameters waiting to be broken. One impulse leads to one idea that leads to another. Hopefully, the final destination will be a new image.

The LIPS print features quite heavily in the Palace collection. Did you choose that print?

We didn’t choose it. We had a call from the gallery [saying that] Palace would like to collaborate with us on a new collection. This was before Covid-19 so immediately it was an exciting prospect — especially as the artwork of interest was [that] print. LIPS is one of our instant coffee ideas that was spun out in a couple minutes in 1973 — made from lips torn from film star’s faces in the pages of magazines that were always lying around our studio — then pasted onto a blackboard. This deconstructed approach in making images became the direction we would explore for the next decade or so. It was completely Dada-esque that we wore identical LIPS Jackets for the Sex Pistols gig at London’s 100 Club in 1976.

What was it about the DNA of Palace that you felt resonated with what you have always created? And how did the collaboration begin?

Palace is seen to be a unique concept store with more positive directions in street art, skateboarding and fashion since its inauguration than most other fashion companies. How could we not be interested? Paul met the Palace team at the Museum Street Gallery and the contract was signed. We met up with Palace at the next gallery private viewing to discuss the way they would convert our print images to these “Mauf” designs on hoodies, T-shirts and denim.

In the 21st century, popular art sometimes may achieve the significance and appeal of works belonging to the world of fine art. There is a strong tidal wave of creativity moving in that direction through interactions between all levels of fine art, design, fashion, dance, video, et cetera. It’s not a tsunami, but there is a tumultuous force which is set to be tapped into throughout the next century. We felt the DNA of Palace was close to our heart.

Who do you consider to be a modern pioneer?

In music, we love Christine and The Queens and Billie Eilish. In art, Damien Hirst, Gavin Turk and Jeff Koons. We watch the movies of David Lynch over and over. In fashion, it’s almost all retro and regenerated classics — nothing much is new. The modern pioneers are about to [step forward]. They are behind the scenes.

Does punk still exist?

Punk music originated in the 60s, and I could write a thousand words about the great punk songs that opened up the doors to so-called punk fashion and culture. Molly and I feel we’ve been within this punk culture all our lives and forever will be. We don’t really see it as ‘punk’ because it’s within our own manner of expression. We are the artists we are because of the works we make not because we are part of any particular genre or cultural movement, but we guess punk came after our early so-called ‘punk’ works, the LIPS print being one of them.

As we’ve already stated, “We were too early for punk and too late for pop.” Both still exist and are doing well somewhere in the world. ‘Punk’ is not a very promising term for such a creative genre that has crossed the lines of all levels of art and culture, promising a natural curve of anarchy and experimentation. It is a diverse concept, and will always exist in some corner of the globe by the characterisation of its visual language, its pure opportunism and its raw edge.

Palace’s Autumn 2020 collection is available in stores this month

Credits

All imagery courtesy of Palace and shot by Angelo Pennetta