The coronavirus pandemic might have disproportionately impacted some of the most marginalised communities the world over. But migrant domestic workers in Lebanon, Jordan and the Gulf countries have often been side-lined from this global discourse. 23 million domestic workers, most of whom are women from African and Asian countries, are currently trapped under the Kafala system. The employment system lures migrant workers with false promises of a better life or higher salaries, so they can provide for their families at home, but most find poor working conditions for little pay (and are legally bound to their employers). Covid-19 has further marginalised these workers, with hundreds abandoned outside embassies, left homeless or confined in their employers’ homes without pay.

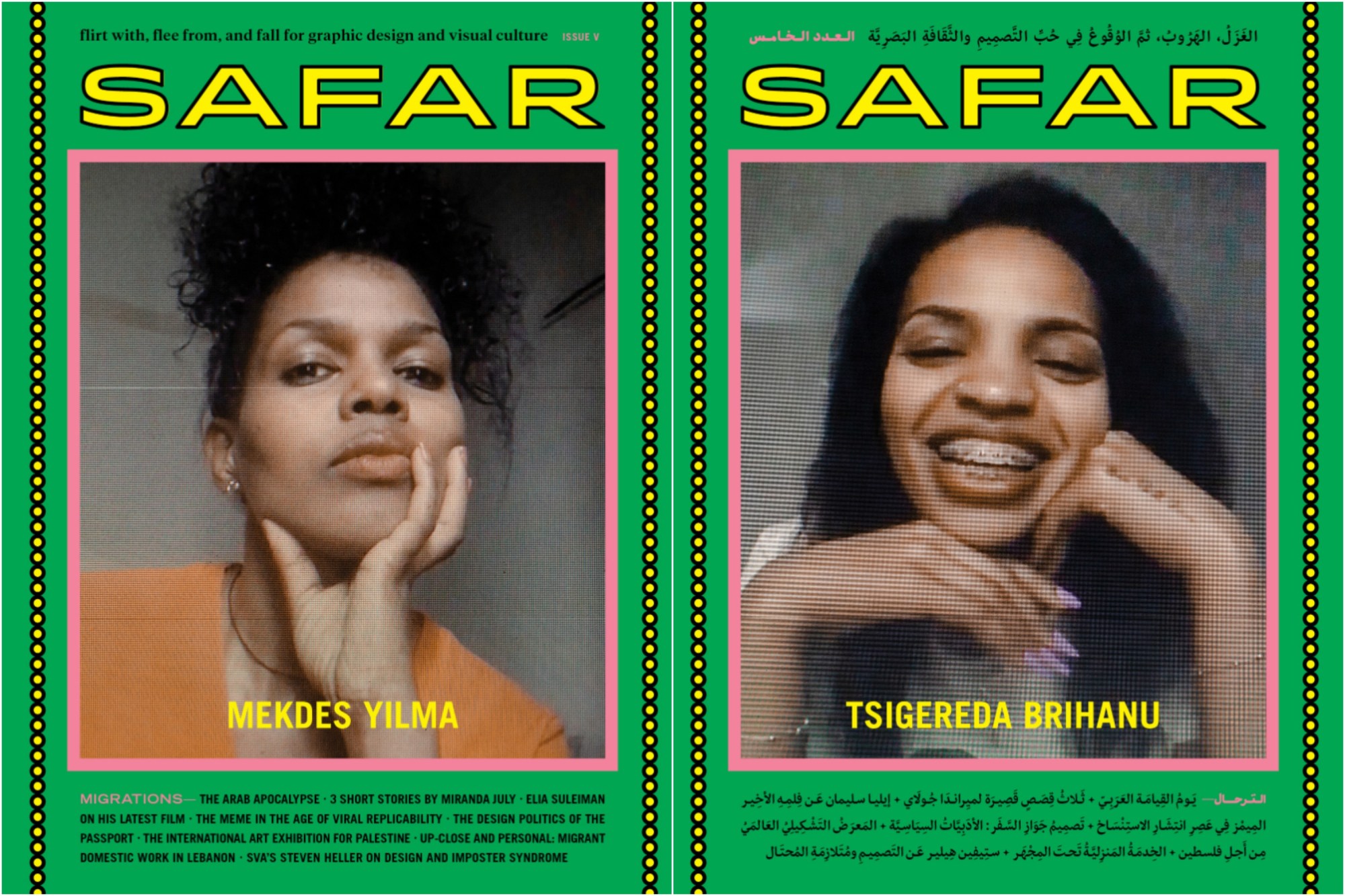

But in reducing domestic workers to statistics, rarely do we celebrate them in their own right or pay tribute to the often thankless contributions they make to their respective countries. It’s this that propelled Maya Moumne and Hatem Imam, co-founders of Beirut-based bilingual, biannual magazine Journal Safar, to dedicate their latest and fifth issue “Migrations” to humanising the women who work under Kafala, while also shedding light on the challenges and dangers domestic workers face in Lebanon. Its covers of two domestic workers are testament to this: one stares assertively at the camera while the other smiles, evoking a sense of agency and playfulness so often denied to them. The issue couldn’t be timelier. Incentivised by protests against racial inequality across the world, including in the Middle East, Lebanese activists have since renewed their calls to abolish Kafala.

Spanning art, photography and writing from contributors as far afield as Berlin and Jeddah, spreads touch on anti-Blackness in the Arab world, the design politics of passports past and present, and gendered experiences of migration. Ultimately, Journal Safar contributes to a broader narrative of migration beyond a Western lens.

To celebrate the release of “Migrations,” i-D caught up with Maya and Hatem to find out more about how the issue came to be, why it’s time to honour migrant domestic workers in their own right and what they hope to achieve.

How did “Migrations” come to be?

Migration has, of course, been an especially urgent subject in recent years. The European migrant crisis or refugee crisis, which reached its peak in 2015 to 2016, has often been at the center of that discussion and with that, the notion of migration has often been linked immediately to exclusion, violence and xenophobia. The same images of refugee families, for example, arriving to Lesbos, Greece, have circulated almost incessantly. But here in Beirut, and in neighbouring cities, different tales of migration and displacement have long been a part of our everyday, and often don’t get international air time. Journal Safar wanted to engage with and share different voices of migration than those shared by traditional media, to challenge the singular pre-existing discourse on migration – and also to assert a more humanising one.

How did the idea for illuminating the Kafala system in Lebanon first come about?

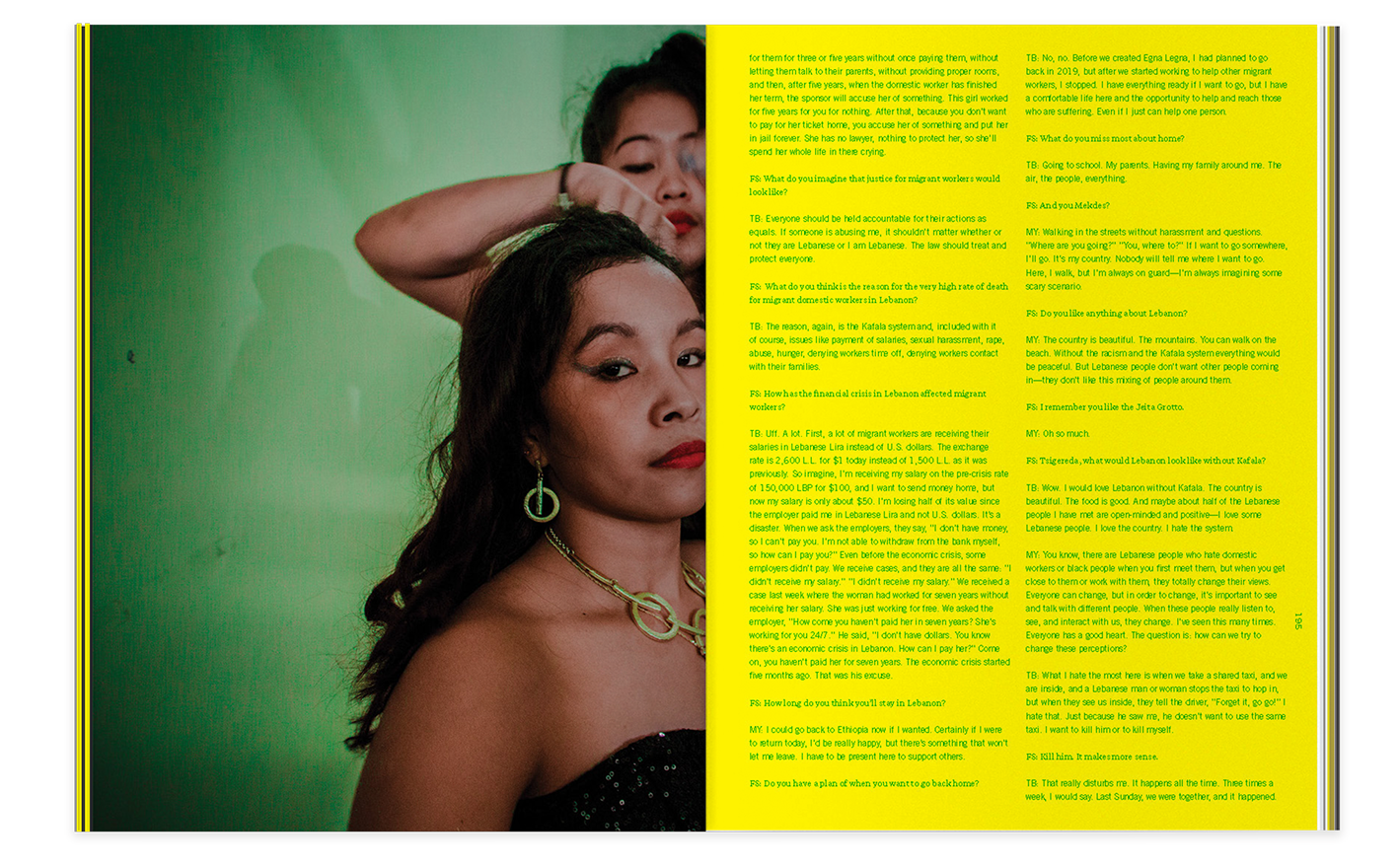

In 2015, photographer Myriam Boulos started her piece, “Sunday,” where she photographed migrant domestic workers in Lebanon on the one day of the week that’s technically supposed to be their day off. We knew that we wanted to publish Boulos’ piece in this issue because it offered an intimate account of the women who are living under Kafala, a word that translates to ‘sponsorship’. The images alone weren’t enough. We then contacted Farah Salka, the co-founder and director of the Migrant Community Center in Lebanon, who introduced us to Mekdes Yilma and Tsigereda Brihanu, two powerful Ethiopian women who came to Lebanon as domestic workers and now run Egna Legna, a collective that defends the rights of their fellow workers. This resulted in the heartfelt interview and the photoshoot via Zoom that Myriam took featuring their portraits on the magazine’s two covers.

Why do you think now is the right time to shed light on the challenges and dangers migrant domestic workers in Lebanon face, and the work they’re doing to abolish this?

The time to raise awareness of this is long overdue. Unfortunately, many issues in Lebanese society have been left untouched for decades but particularly since the start of the protests in October 2019, people are beginning to speak out more about the injustices they see and experience. Kafala is easily one of the biggest and most obvious of those injustices.

Domestic workers are rarely offered a platform on their own terms but here they’re celebrated, honoured and – crucially – humanised in their own right. How much of this was intentional?

This was entirely intentional. So often the Kafala system is measured in gruesome statistics and only talked about when a woman takes her own life, literally unable to continue living under this oppressive system. Lebanese ‘employers’ of migrant domestic workers – even in the best of circumstances – very often fail to recognise and treat the women who come to work here as full and human equals. The Kafala system is thus predicated on dehumanization and so recognising their humanity is crucial to dismantling it.

Is this issue for Lebanese readers or for a global readership to learn more about the challenges migrant workers can face in Lebanon?

We try to select a diverse set of articles and topics around the issue’s theme that will inevitably expose every reader to something new. Even if Lebanese readers are well aware of the Kafala system, for example, they likely haven’t thought about how it manifests itself architecturally in the building laws of Lebanon. Our piece, “The Maid’s Room”, offers them insight about how legislation and design come together to create such a control system.

A lot of the spreads focus on migrant women’s experiences – why did you choose to focus on the gendered experiences of migrant domestic workers?

Most of the migrant domestic workers who come to Lebanon via the Kafala system are women. Although not only women migrate to Lebanon to work, non-women domestic workers are very uncommon. That being said, the domain of the house – of someone else’s house – is particularly dangerous for women coming to work. Sexual violence and harassment are rampant under the Kafala system: women in this system have no way to leave or to get away from their attackers because they work, live and sleep under the same roof, and their sponsor family usually even holds their travel documents.

Have you faced hostility from readers since the publication of “Migrations?”

We’re overwhelmed by the reception this issue is getting. We’ve had a constant stream of messages. There’s a huge amount of denial in Arab communities regarding the Kafala system. The level of bigotry was unbearable to witness in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, where we heard many voices of solidarity that failed to acknowledge our own form of systemic violence and subjugation at home.

Do you hope that this issue might create a shift when it comes to calling for the justice and dignity of domestic workers in Lebanon?

We hope readers will think a little bit different about what migration looks like after reading this issue. Of course we hope that it can spread awareness, especially at an international level, but Journal Safar certainly isn’t the most important organisation fighting for the dignity and rights of domestic workers in Lebanon. Tsigereda and Mekdes along with two other women, Banchi and Genet, run Egna Legna that does really important work to support migrant workers here in Lebanon.

Lebanon is collapsing economically which has put an especially huge strain on migrant domestic workers, many of whom have been unable to return to their home countries because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Egna Legna has stepped in, raising money to make sure that women in this situation have access to food, clothing and shelter. The Migrant Community Center, too, is also an incredibly important space for migrant domestic workers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Order Journal Safar Issue 5 here.