About four years ago members of the young drag community of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, would discreetly come together in an undisclosed bar to attend drag competitions. The events would follow the universal formula of a drag ball: participants would parade a runway and showcase their latest and finest creations, as much to each other as to members of a jury. At the end, a winner would be picked, and would take home the grand prize. A true display of opulence, craft, confidence and creativity, the competitions ran for about two years, before the community unfortunately decided to disband due to adversities they faced.

While the competitions have been off since then, the desire to create and self-express never lessened. Take Kesse Ane Assande Elvis Presley, or ‘Britney Spears’ to friends, and Mohamed, aka ‘Baba’, as examples — two fierce Abidjan queens with great ambitions. Britney, who once described her aesthetic as “Christ in the underworld” aspires to be a model, actress, and international drag star — but, most importantly, she just wants to have the freedom to do what she wants, and be proud of the life she leads. Baba would like to own a fashion company, start a family and work in the entertainment industry. These are aspirations common to many young creatives around the world, but in a country (and continent, for that matter) that has been oppressive towards its LGBTQ+ communities post colonisation, they aren’t so self-evident.

Sierra Leonean visual artist Ngadi Smart had been documenting subcultures on the African continent and beyond for some time — capturing the eclectic attendees of the Abissa festival in Grand-Bassam, or young creatives in their homes in Toronto — when a fellow queer friend who had been to one of the drag events in Abidjan showed her a photo of a queen in an amazing outfit. That person was Baba. She got in contact with the people who organised the events, went to their bar and met with them. They, in turn, placed her in contact with the queens, who she spoke with and, ultimately, got to know.

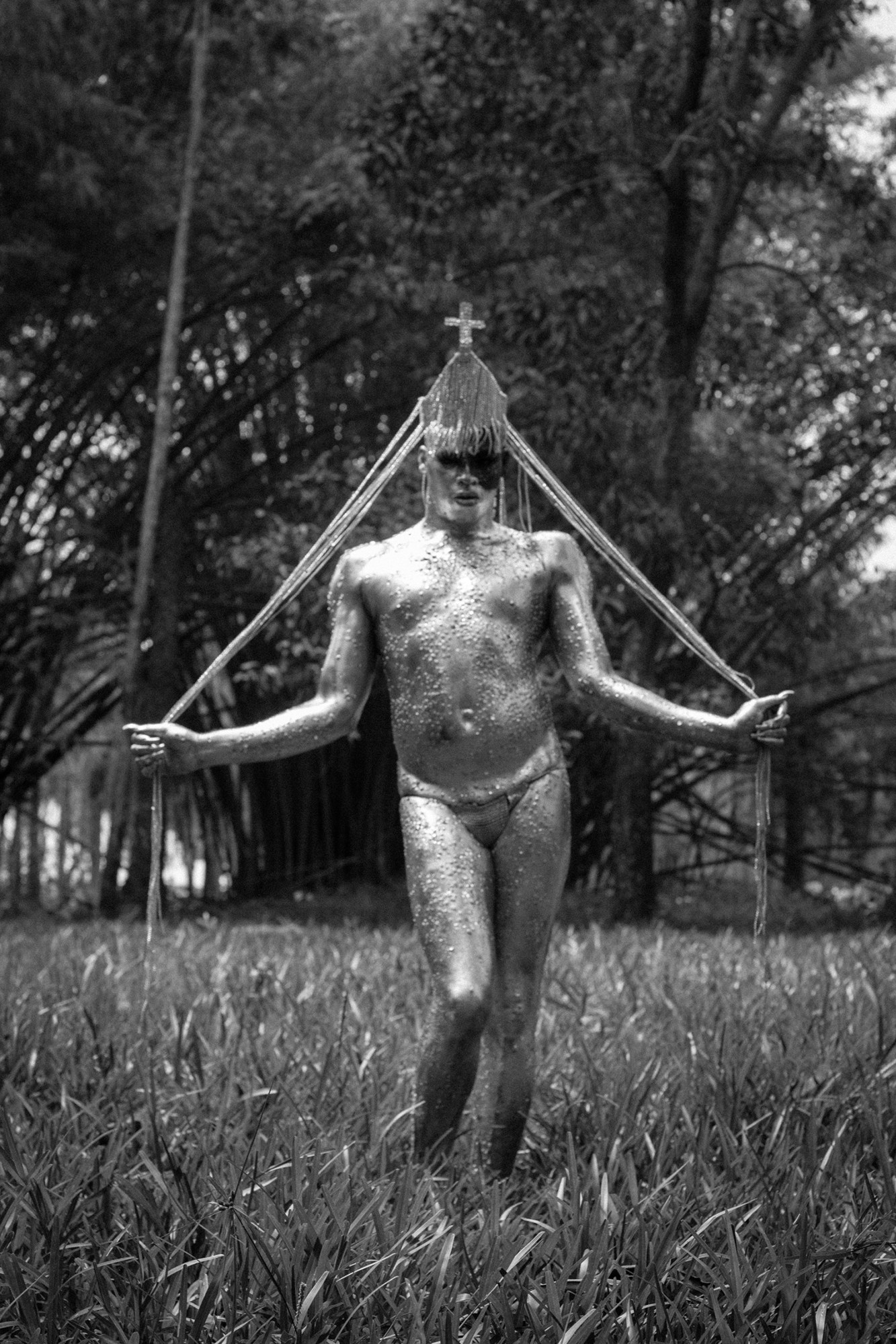

In her latest series, Queens of Babi, she’s captured Britney and Baba in all their radiant, rhinestoned beauty against a wooded backdrop. “There was something in their aura that attracted me to them,” Ngadi explains. “They were flamboyant, yes, and confident, but while discussing their ideas for the shoot I was blown away not only by their confidence, but also by a certain je ne sais quoi.”

Practising your art as a drag queen in Côte d’Ivoire, however, comes with its obstacles, Ngadi says. “Plenty of recent surveys show that the overwhelming majority of people who live in Africa strongly disapprove of homosexuality. There is hardly any reporting on LGBTQ+ communities in Francophone African societies, and mobilising them on a community level is a relatively new phenomenon.” Take Abidjan for example, where there are no real LGBTQ+ organisations. Members she’s photographed told her how they were often unable to go into certain neighbourhoods out of fear of being assaulted, or even losing their lives. “Through my photography, I want to change Africans’ perception of the community by sharing their stories, as they reflect true human rights issues,” she adds. “I want to support these drag queens in their endeavours to improve their lives, including things such as setting up an LGBTQ+ association for them.”

Apart from supporting the drag community, however, she’s also on another mission with her work. According to Ngadi, it’s time that the world be introduced to works documenting Black sensuality and culture through an African lens. “I believe that this theme isn’t sufficiently represented from a Black point of view, and I strongly feel that the world needs more of it.” For too long, Black bodies have been the subject of exoticism and dehumanisation within the art world, Ngadi continues. “It’s time that the spectrum of Black sexual identities and genders are seen as normal, as opposed to being othered.”

On account of her work, Ngadi has quickly been dubbed ‘an African photographer-to-watch’ by international media outlets. But, while it’s nice to be considered part of this ‘new Black vanguard’, the photographer says it’s even more amazing to see a generation of young creatives emerging on the continent. “What excites me the most is that as African creatives we now have the tools to tell our own story, do it in our own way and reach a large audience. We are the ones experiencing the various aspects of what it means to be African in the present age,” Ngadi says. “It is great that we get to define for ourselves what African art is and what African art represents in modern times.

“Simply through visual storytelling, whatever theme or medium we choose, as well as through the quality of our work, we can challenge perceptions of the African continent, and showcase a genuine representation of modern African visual art,” she continues.

It is uncertain what the future for this small, emerging community in Cote d’Ivoire holds, but Ngadi hopes that it at least entails more freedom than they are experiencing now. “I’d like to quote Baba who said that it is her hope to see the drag community flourish, that people start understanding that drag is art and they need to start giving us the respect and credit we deserve.”

Credits

Photography Ngadi Smart