In 1956, Allen Ginsberg published “Howl”, an epic poem that had a seismic impact on the American literary scene. Evoking the anxieties of the atomic age, the poem referenced taboo subjects: homosexuality, psychedelic drugs and anti-capitalism. In 1957, it triggered a widely-publicised obscenity trial that changed attitudes towards censorship in the US.

Ginsberg’s poem launched a counterculture and captured the freewheeling spirit of the Beat Generation (a name taken from jazz music of the 40s). In the late 50s, the young bohemian and his closest friends – among them Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs – flocked to New York’s Greenwich Village. Non-conformist and uninhibited in their lifestyles and literary approaches, they embraced unfettered personal, political and sexual expression. Keeping in the spirit of “Howl”, their modus operandi was: “Follow your inner moonlight, don’t hide the madness.”

Today, most people remember Ginsberg as a poet-activist-provocateur who had a penchant for exhibitionism (he was known to occasionally strip naked on stage). But he was also an avid photographer. An exhibition dedicated to his photography Muses & Self: Photographs by Allen Ginsberg (open until 23 September 2023 at Los Angeles’ Fahey/Klein Gallery) reveals his tender, if intermittent, observation of his inner literary circle between the early 50s and 1997 — the year of his death. “Sharing the intimacy of his friendships in photographs could be seen as a parallel to the intimacy of his poetry,” Peter Hale of the Ginsberg Estate says. “The photographs reflect his approach to writing… stopping to see things more clearly, or freezing a moment in time.”

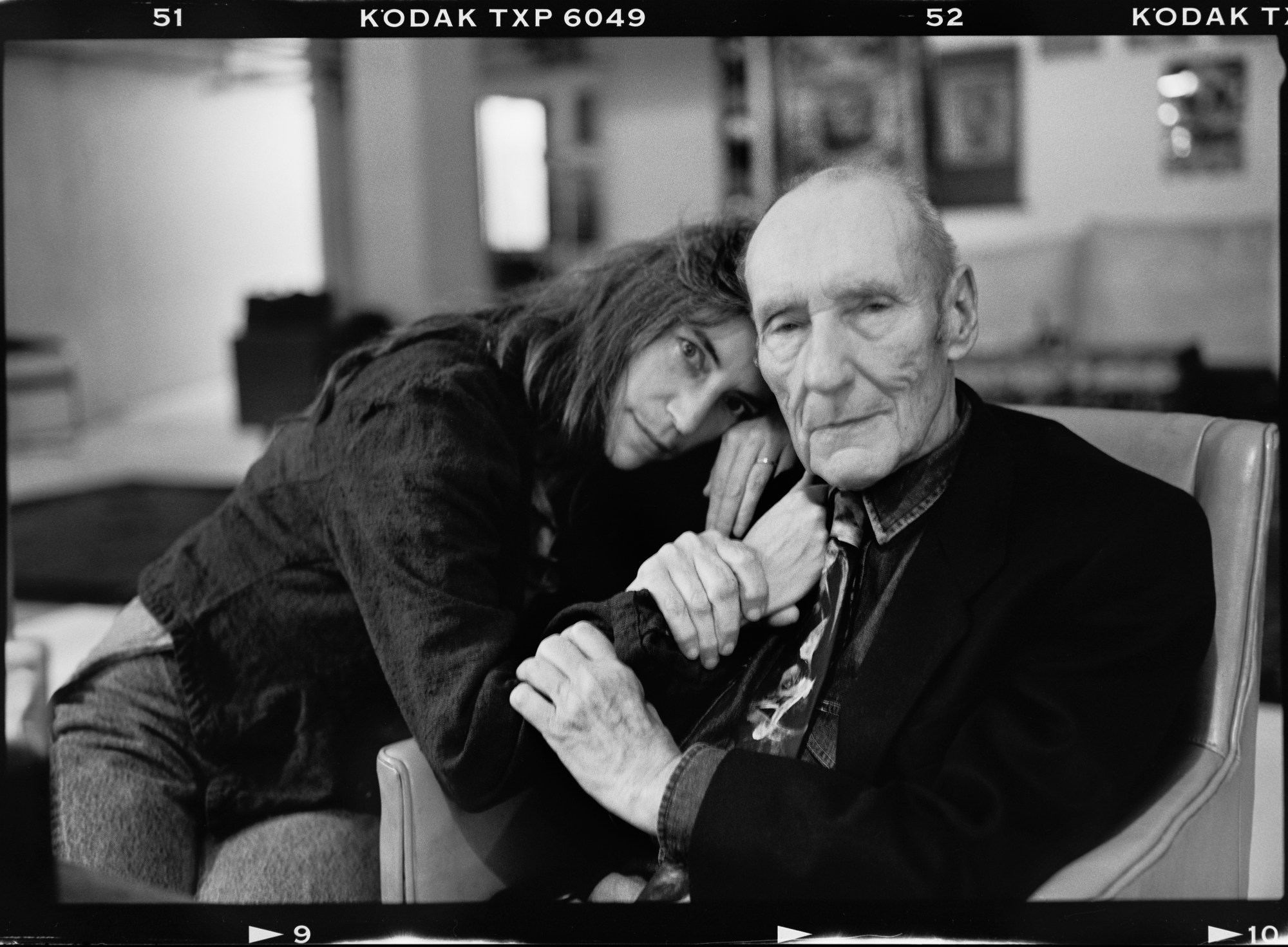

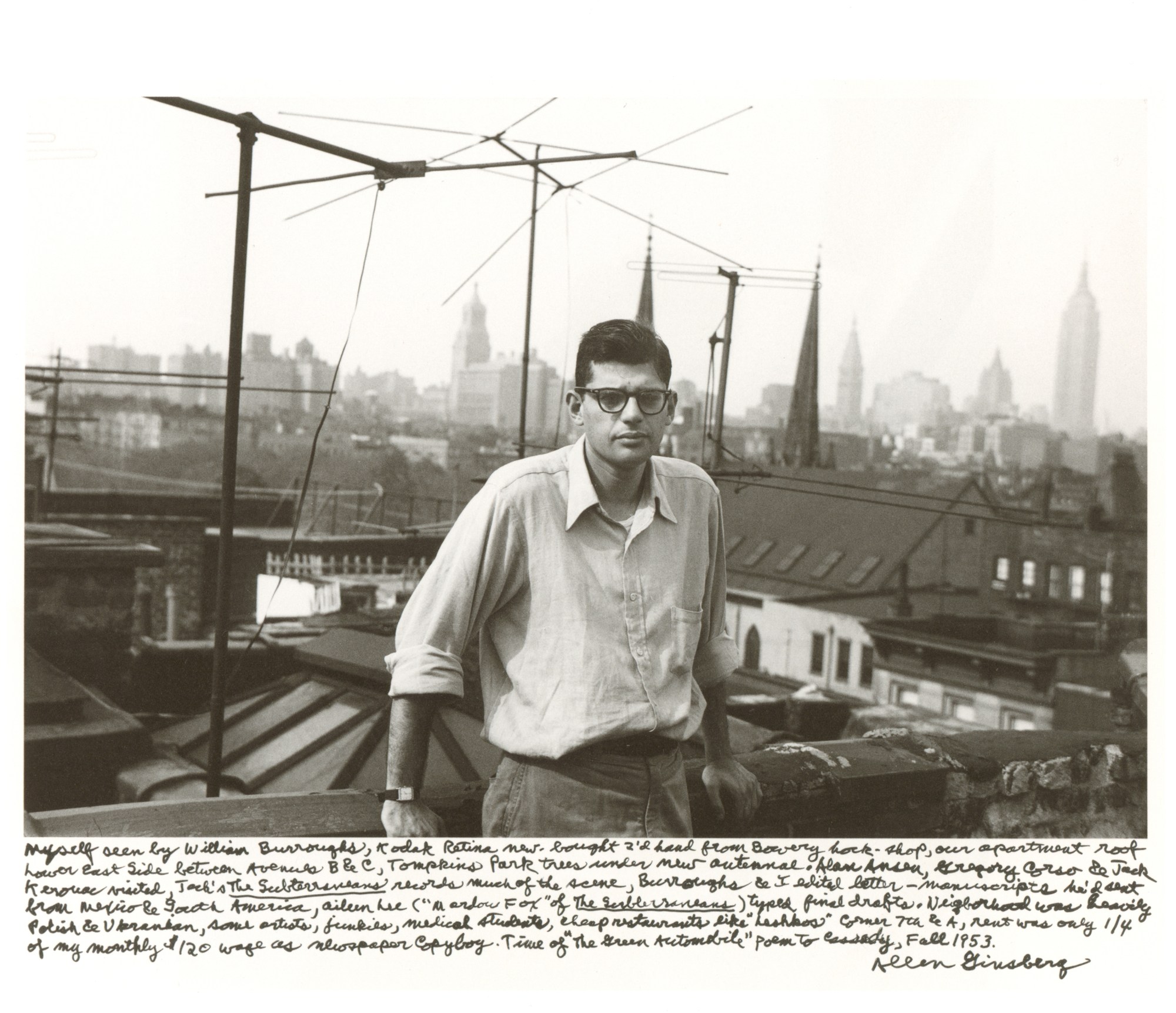

Capturing Kerouac, as well as Arthur Miller, David Hockney, Francesco Clemente, Giorgio Armani and Patti Smith amongst other legendary creatives, the exhibition reveals Ginsberg’s key position in an avant-garde movement. It chronicles the evolution of his photographs across decades, beginning with his earliest forays into photography shortly before penning “Howl” – a moment that catapulted him into celebrity. “He took some very early photos of Kerouac and Burroughs in 1944,” Peter says. “But the real start to his photography came in 1953. He bought a Kodak Retina at a used camera shop and took several rolls at his East 7th Street apartment in the Lower East Side.”

By 1953, Ginsberg was 27 and had graduated from Columbia University where he formed close bonds with Burroughs and Kerouac (both of whom became his lovers). At Columbia, he earned a reputation for wild and disreputable behaviour. At one point, he allegedly faced prosecution for using his college dorm room to harbour the stolen items of an acquaintance. He subsequently spent several months in a psychiatric ward as part of a plea bargain (some have argued it was an unsuccessful attempt to stamp out his homosexuality). The themes of consciousness, hallucinations and madness would repeatedly show up in Ginsberg’s writing, referencing his recreational use of psychedelics and possibly the fact that his own mother was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Metaphorically, the theme of madness in his work also spoke to the repression of post-war society. “Howl” famously begins: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked…”

His intense observation – be it through his camera or conveyed in text – highlight Ginsberg’s heightened sensitivity. His shrewd ability to observe the world, and to articulate what lay beneath the messaging of Red Scare-era politics and rising materialism, permeated his vision. Ginsberg was made to feel like a deviant as a queer man in a puritanical culture; his work, inversely, pointed to the irrational nature of that framing.

Speaking about his experimentations with photography in 1953, when he was having an affair with Burroughs (whom he affectionately called ‘Bill’), Ginsberg recalled: “I think he was pleased that I would want to take his picture nude from the waist up (he had his underwear on). I was taking advantage of the intimacy as an excuse to invade his privacy, take him more naked than he would normally show himself. We took it for granted that the world was a little crazy if it saw our friendship and sense of sacramental respect for each other to be neurotica, sick, weird, or strange.”

Photographing his male lovers in moments of intimacy was a form of personal indulgence, but also, subconsciously, an act of political resistance. “The mutual respect between us was contrary to what was taken for emotional and psychological reality in those days,” Ginsberg wrote. “[The 50s] was the beginning of the ‘American Century’, hyper-militarisation, the Atomic Era and the Age of Advertising, of Orwellian double-think public language. The candour of tenderness which Bill and I expressed to each other seemed different from the ‘square’ mentality of public discourse.”

Ginsberg accompanied many of his photographs with hand-written text, a custom he borrowed from the photographer Elsa Dorfman. He would “initially write the name, date, and place” of each photograph, Peter says, while allowing his writing to “expand upon what his subjects were writing at that time.” Each shot was a vignette of an intimate social or creative moment set against the broader literary or economic landscape. For example, the caption on Ginsberg’s self portrait reads: “Myself seen by William Burroughs, Kodak Retina new-bought 2’d hand from Bowery hock-shop, our apartment roof Lower East Side between Avenues B & C, Tompkins Park trees under new antennae…Neighborhood was heavily Polish & Ukranian [sic], some artists, junkies, medical students, cheap restaurants like ‘Leshkos’ corner 7th & A, rent was only ¼ of my monthly $120 wage as newspaper copyboy. Time of ‘The Green Automobile’ poem to Cassady, Fall 1953.”

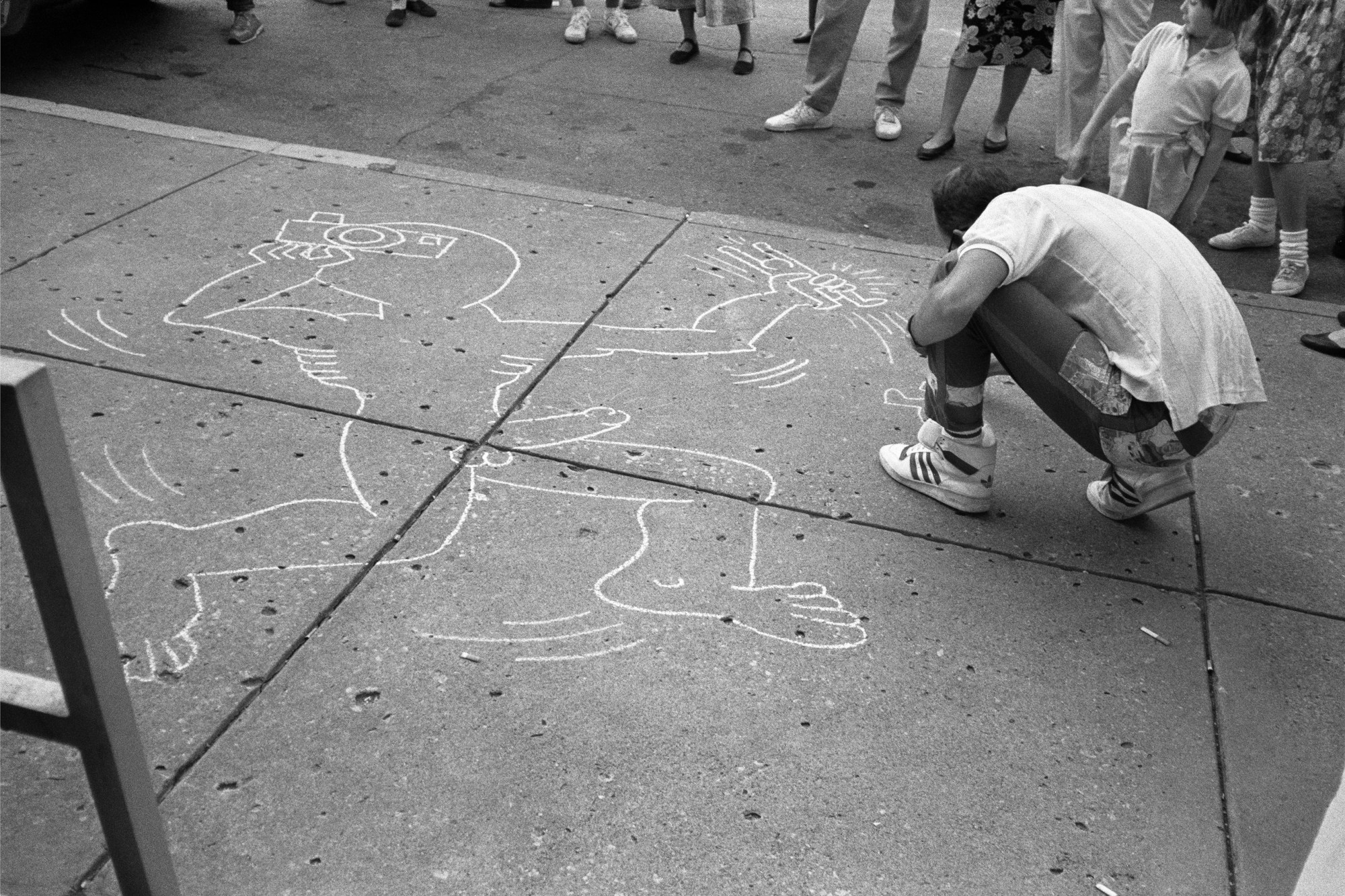

After losing his beloved Kodak camera in 1963, Ginsberg abandoned photography in the 70s. By the 80s, his interest returned, particularly after becoming friends with the legendary photographers Robert Frank and Berenice Abbott. They introduced him to better equipment and he embarked on what he would call ‘continuous reportage’. According to Peter, “This period through the late 80s is his richest, with almost every contact sheet producing something significant.” His love for photography began to eclipse his pursuits in writing: “As a matter of habit, I carry a camera where I used to carry a notebook,” Ginsberg wrote. “I’m finding that I write less and less in my notebooks now – I do my sketching and observing with the camera instead.”

For Ginsberg, the camera was a tool for intimacy and preservation of memory – a means to promote the legacy of the intellectual counterculture to which he belonged. Through his “sacramental” approach to photography, he immortalised his friends and lovers over decades – and with that, the riotous and radical spirit of the Beats.

Credits

All images © Allen Ginsberg, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles