At the core of AdeY’s work is a desire to normalise rather than fetishise nudity and human connection. A standpoint that was solidified, he says, after standing in the duty free section in an airport, and looking at perfume adverts for more than the usual half a second. There, he saw women draped over big perfume bottles in stories that made absolutely no sense — the overt sexualisation of commercial photography that uses the womanly body to sell products hit him as particularly disturbing, and something he wanted to counter. “It was the weirdest world,” he says. “I was sure you could do photography with nude bodies that weren’t sexualised in any way. So that was kind of my mission, setting out to do that.”

As a contemporary dancer first, AdeY worked for small companies in London, putting on direct movement-based, modern contemporary dance duets and quartets around England. Later, in Sweden, he joined a company of 16 dancers that saw him perform at the Opera House, as well as more conceptual shows — an awareness and celebration of the body comes naturally to AdeY. But the dancing, on its own, couldn’t satisfy him completely. When you’re a dancer, “you’re the paint for someone to brush, you’re somebody else’s vision all the time,” he explains. “You’re trying to physicalise someone’s idea, but if you have your own aspirations and desire to be a maker, it’s very hard… You feel like your voice is screaming, and that’s what I felt all the time.”

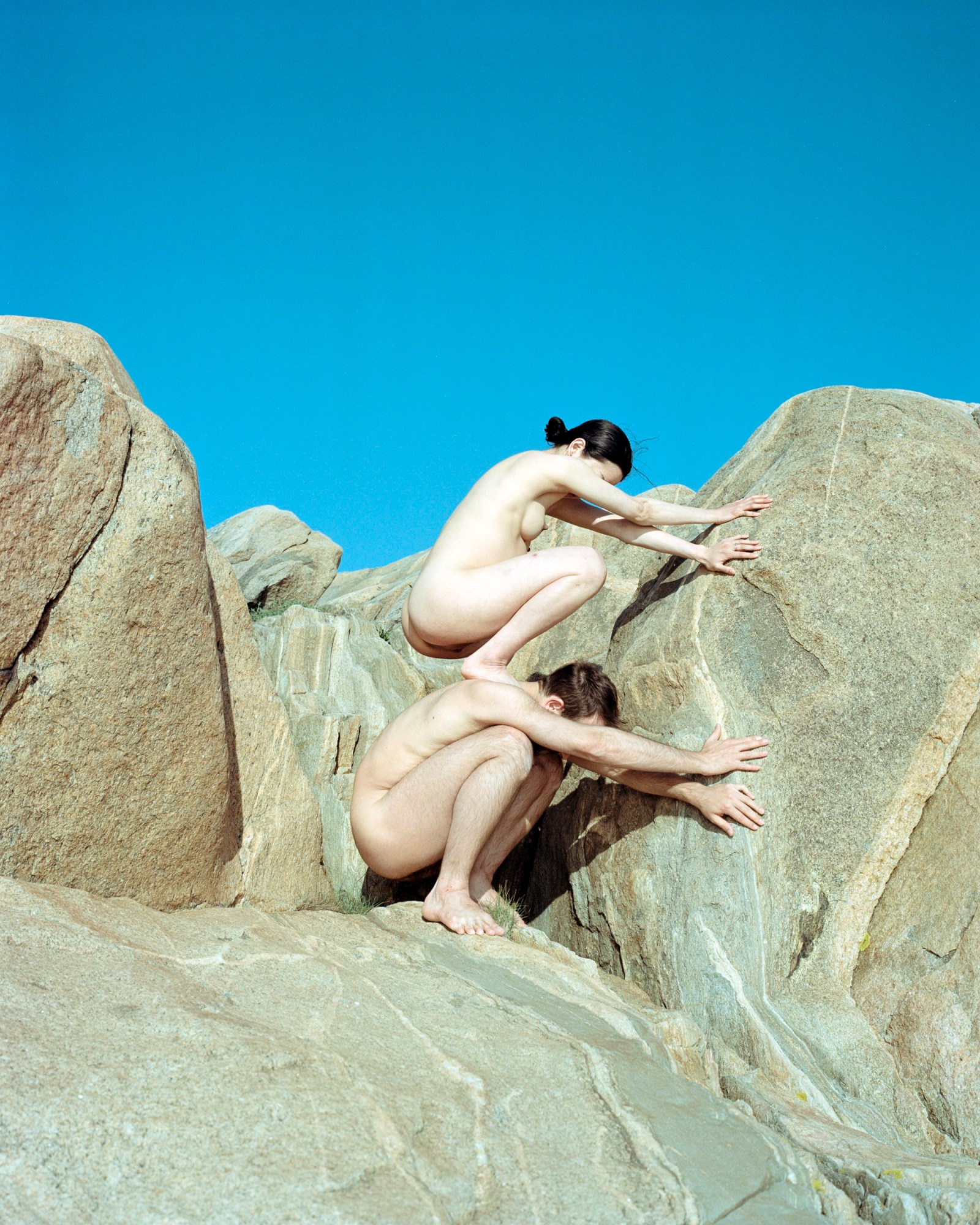

By 2014, AdeY had started experimenting with his own ideas, choreographing performance artworks and throwing himself into his photography, which had been a hobby up until this point. He reached out to his collective of performance artist and dancer friends, and asked to photograph them in the nude. Ultimately, creating the very physical compositions he’s known for today, that test the limits of the human body’s balance and strength: women holding men, a dozen dancers leaning against each other like dominos, two men kissing while one is upside down, or women spilling out of a traditional Korean hanok. Complimenting the naked bodies are beautifully bleak environments: grand empty houses, grassy fields, stairways in the sea and disregarded factory buildings, that add to a sense of isolation that is at the heart of much of his work.

“I think loneliness was something very strong in some of my early works,” AdeY explains. “That feeling of being in an urban space, and feeling alone even though you’re surrounded by so many people. You can be so close to somebody in physical distance, yet feel so alone and deserted.” By adding nudity into the equation, he exacerbates this — the vulnerability, isolation, anxiety and depression that appear to play a central role in the human condition — producing images where nakedness and touch do not always translate to intimacy, sexuality or affection, but can instead highlight the separateness of two people’s emotions and ideas.

But on the flip side of his work, there’s also a strong sense of fun and freedom. Based on a concept that everybody in the images are children, in the sense that they are innocent and society hasn’t corrupted their pure view of the world, men and women literally dance around, free. In a way, the images are AdeY’s “dream for a future that could maybe happen, where we could run around and just have fun”. They are a utopian world, where there’s equality of sexuality, gender and race.

One photograph that AdeY shared recently on his Instagram, in light of the Black Lives Matter protests that have successfully proliferated across the world, depicts two white women lifting up a Black man. It’s taken in an unappealing apartment in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, and came about rather organically — two of the dancers suggesting that they lift him up. At the time, as someone on the outside taking the composition in, he knew the picture would become a positive beacon — a symbol of our collective strength, raising this person up.

From the beginning, AdeY was certain that he didn’t want his images to center any particular individual. Countering commercial photography that’s about how sexy the body is and how beautiful the face is, he instead chooses to keep the identity of his subjects hidden or obscured in some way. As time has gone on, more faces have been revealed, he claims, but it’s more important to look at what the body is saying in relationship with the space and in synchronisation with other people than focus on a person’s physical features.

To give the photographs their signature de-saturated hue and graininess, a Scandanavian-approved look of grey-toned minimalism — everything is captured on a film camera. Yet the medium format Hasselblad, and more recently his Fuji GH670 or Mamiya 7 cameras are more than simply an aesthetic choice. They allow AdeY to be spontaneous and sporadic in how he takes his photographs, using film allows him to maintain a rhythm with his subjects, to talk to and keep them relaxed, which is particularly important when everyone is naked.

Although he mostly works with friends — “people who are working with their body, and don’t have the same fear that other people do” when it comes to nudity — he also travels abroad and photographs new subjects. “Something I’ve noticed is when people take off their clothes, their body language changes slightly… the body gets a bit more shy, subconsciously,” AdeY says. “But it’s amazing how quickly that changes, people just adapt and the body is like, ok, this is the new reality.”

It’s a normality that AdeY would love to exist in the world outside his pictures too, but sadly the censorship of art on social media reinforces negative connotations surrounding nakedness. When you share your work on social media platforms, especially Facebook and Instagram, blurring an exposed nipple or obscuring male genitalia, you’re essentially sexualising your own work by covering people up. “I’ve kind of highlighted that part should be hidden,” AdeY explains, “and then [social media] is kind of sexualising it.”

AdeY’s account has been deleted nine times in the course of about a year and a half, and while he’s always had his reinstated, there are so many other artists that have had their work removed even though it’s not of a sexual nature. It’s something AdeY thinks is particularly damaging when celebrities such as Kim Kardashian (“I’m sure she’s a lovely person”), is promoting a body ideal that’s unachievable for the majority of people. But artists “who do much less dangerous or risky work are silenced by social media.”

“I don’t airbrush anything,” AdeY continues. “I don’t edit anything, so when you have to censor something within it, it feels so disappointing and sad and it makes no sense to me.”

Through his work, AdeY attempts to create a non-sexualised and open-minded representation of human beings, based on the dream of acceptance. His photographs of entwined bodies are more than portraits of people, they are politically motivated images that make a comment about the society in which we live, and explore the surroundings that define who we are and how we are seen. Although the images are able to transcend time and space in many ways, they are also firmly rooted in the present moment.

A few of AdeY’s images can be found in BOYS! BOYS! BOYS! edited by Ghislain Pascal, available online. All the profits from the book will go to the Elton John AIDS Foundation.