According to experts in clubbing, the UK is on course to experience a “summer of rave” not unlike that of 30 years ago. Months of lockdown boredom and a lack of nightclubs, house parties and festivals has given way to a sharp rise in popularity of makeshift parties in warehouses, car parks and fields.

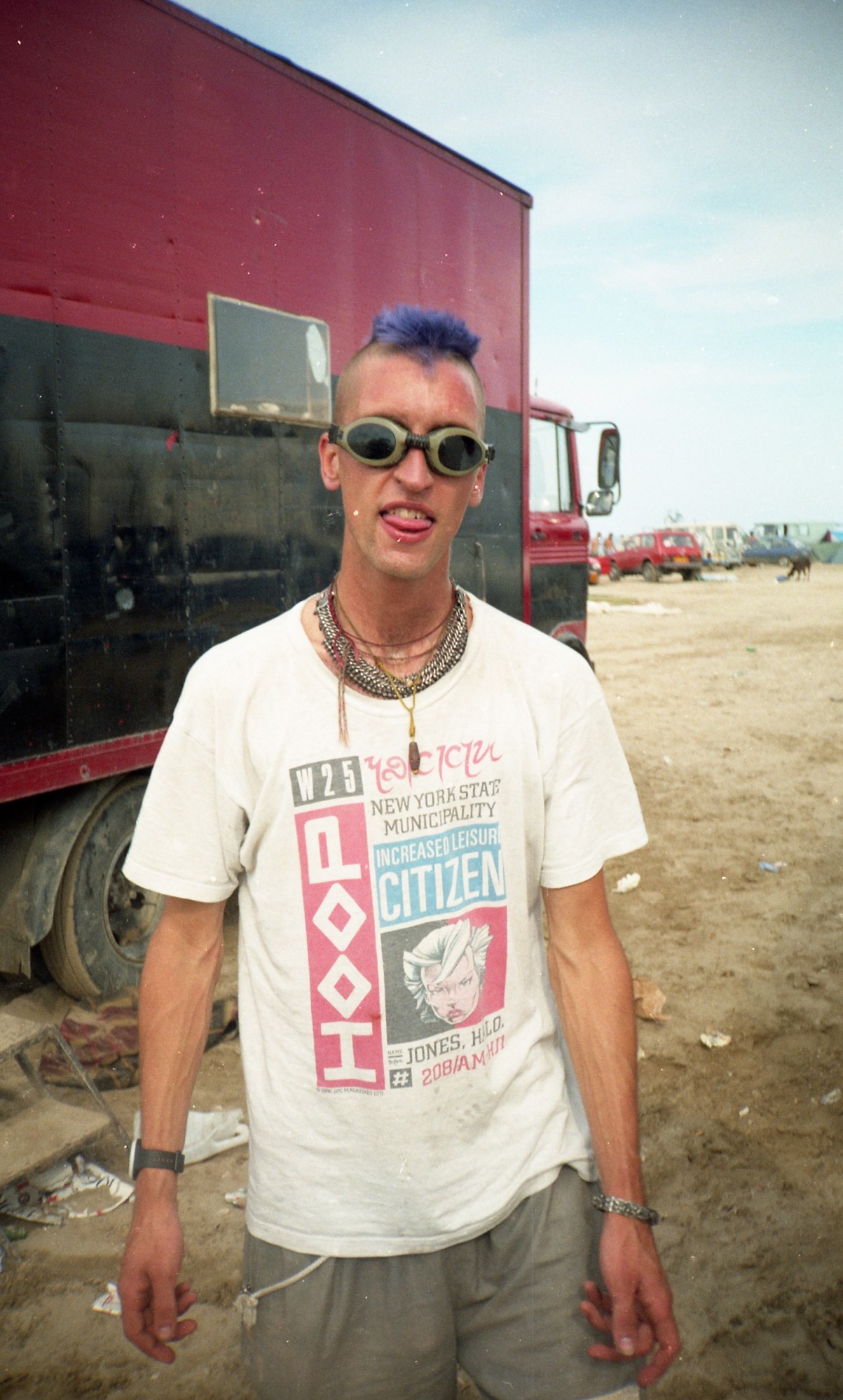

Artist Seana Gavin knows a thing or two about such parties. Back in the 90s, she travelled with sound systems including the Spiral Tribe, a fabled collective of nomadic party animals that hosted illegal raves with their mobile sound system, first in London, then, as the government began to legislate against their existence, across the continent. Her new book, Spiralled, published by IDEA, lays bare the life of a ‘Spiral Baby’ through her meticulous photographing and diarising of the period.

Beginning around 1993, a little while after the “Second Summer of Love”, we first find Seana and her friends at the sharp end of well over a decade of Conservative politics. Protests against the police and the government are surging through London’s parks and streets, and the atmosphere of Britain for young people, it seems, was not all too dissimilar to now. In fact, Seana’s first diary entry in the book, describing a protest that escalated into police violence, feels like it could have taken place yesterday. “The riot police on horses chased us through central London,” Seana writes. “Most people were just trying to get home but all the tube stations were shut – so everyone was wandering around lost on foot trying to figure out their journey.”

Back in April at the beginning of lockdown, we spoke to Seana about the creation of Spiralled, and its prescience in 2020. Little did we know this would become all the more true by summer.

There’s some real parallels between the beginning of Spiralled and now. There’s a lot of unrest and a lot of alienation felt towards the government and the police. I wondered what that era felt like at the beginning, around the time of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, and how that compared to now.

Back then I was still at school at that point but everyone I knew, all my friends were living in squats and into alternative living. Everyone was quite politically engaged. With the Criminal Justice Act, it really was going to affect us because they wanted to put in all these rules to make any unlicensed event illegal. Even the right to physically protest was also being questioned. At the Criminal Justice Bill march I wrote about in the book, where I unfortunately got attacked by the police, there were thousands and thousands of people there and it was a real mix of people that attended. There was every generation, it wasn’t just anarchists or whatever. It was something that a lot of people felt strongly about.

If we talk about life before the pandemic, it did feel like there was a lot of parallels with all the Extinction Rebellion stuff that was going on and actually, for me, it felt like the first time since the 90s where young people were becoming so politically engaged. I guess, it’s a natural cycle that happens. In the 60s you had the free love era, and then the punks in the 80s. But after the 90s, it felt like it had kind of gone a bit on hold for a while. It felt like a lot of youth seemed to be more focused on fame and there was a lot of reality TV that came in.

You mention it a little in the prologue to the book that prior to this you had quite a liberal upbringing that allowed you to explore these scenes and parties more readily than some. Do you think looking back at it, you were completely ready and prepared for this?

I had creative and quite political parents. I lived in upstate New York and Woodstock which, as well as the history of the festival in 69, was also a real magnet for alternative living. I think that left its mark on me. I moved around a lot as a kid — back and forth between America and England. I guess when I came back to London I felt I probably never really fitted into an obvious box. My mum was very pro-education so I got into a good secondary school, I had a scholarship, but I never felt I related to those people and so when I started attending the raves and those parties, it felt like I found where I fitted in. It felt more natural, with most people also looking for an alternative outlook on life and rejecting convention. My upbringing set the tone for that.

So, you became a Spiral Baby.

Yes, I was 15, 16. Underage. I did have other friends around that age, but really a lot of the people were quite a bit older, so I guess I was always thought of as a bit of a baby. It was given to people like me who really got into the scene and took on the whole ethos: shaving all the hair off, wearing all black… The other phrase was, when someone really got into it, they would say “Oh, they’ve been spiralled.” Because I was going to these parties every single weekend, religiously, my life started to revolve around it.

I came into the scene in 1993, the year after the Castlemorton party which resulted in a court case and harassment from the authorities and which led to Spiral Tribe leaving the country. But when they were still in London I got to know all of them and when they went to Europe and a lot of the sound systems joined them I would spend long periods of time travelling in my friends’ mobile homes with the sound systems. It would maybe be for the whole summer or I would go out for New Years because I was still at school. Then I ended up at art school, so I was still trying to finish off my degree in between having this split life.

There are parts of the diary entries that read like a teenager’s fantasy summer. One quote that said something like “I was in Berlin for three weeks. I just got into the Berlin lifestyle, I had a laugh.” It sounds idyllic but presumably, there are more difficult aspects to this life and this scene that is maybe not as easy to document in this book?

I don’t see it all through rose tinted glasses. There are diary entries that I wouldn’t have wanted to include in the book. It was a very hardcore scene. The people were very hardcore. But there was also a real sense of community and family and that’s one of the things I took from it and what was so special about it. For those periods of time, even though I was close with my family back in London — I tried to make sure I called them once every couple of weeks to tell them I was still alive — the people I was with were like my temporary family. I would survive entire summers with like a couple hundred quid. You would stretch it out but we would all chip in, everyone would share everything and we would all look out for each other. Eventually I came out of that scene after 10 years because of a loss of a friend. When I dug out these photos for my show in Paris, that was the first time I had really looked through all this material properly in many years and it was the first time I shared those photos to the public.

I guess you could never have known at that time that these would become such valuable documents of a very specific time and a place.

No, exactly, I didn’t really value it. At the time it was just my normal life, those were my friends and that was what I was used to. It was only really as the years have gone on that I’ve realised it was so hidden and underground.

People who retrospectively become these key documenters of scenes and subcultures say that the camera just never had the same resonance back then as it does now. That people were so much less aware of it and so much less conscious of behaving in front of it. Do you find that, looking back at these pictures, that the camera was much less dramatic in a way?

Definitely, back then it was before the days of smartphones. So it was definitely less people that were taking a camera out on a night out. But when I did take people’s photos, there was never really any posy-ness, it was very natural. For me, as soon as selfie culture became a big thing, that’s actually when I stopped taking a camera on a night out.

I interviewed Linda Sterling last year and she said “revolt and rebellion have to happen, in some part in secret, but today there seems to be this collective urge to share everything within seconds.” I imagine you agree with that sentiment and that’s partly why you stopped.

Yeah, it’s true, I think there is a very different mindset to things now that, especially with Instagram. I mean I would be a hypocrite to say I don’t use Instagram because I have become a little bit addicted to it myself. But I think it’s actually stopping you from being present and enjoying that moment. Putting together a post for Instagram actually takes a bit of thought! I think that’s what is so great about Berghain, it’s the only place I’ve been to in recent years where they confiscate your phone when you go in, so it means you’re completely experiencing it.

I believe the last entry from your diary in the book says, “we returned to London with the feeling that it was going to be an amazing year. I felt so energised and excited for what the future had in store.” I was just wondering what that next period was like in your life? After the book closes.

It’s a bit sad actually. I remember that was such an amazing New Year’s Eve party near Barcelona and we were all on such a high and unfortunately when I came back to London, a couple of months later my friend died, the one the book is dedicated to. So for me that was kind of the end. It’s funny, in a way it kind of feels the same as this New Year’s Eve, 2020, which was such a massive thing. We were like, “Oh wow, it’s 2020, it’s a round number, it sounds really futuristic” and I had a great time thinking it was going to be such an amazing year. Then, two months later and it turns into this crazy world-wide pandemic. Yeah so, sadly that year wasn’t what I had hoped for when I had written that diary entry.

Seana Gavin’s ‘Spiralled’ is published by IDEA.

Credits

All images courtesy Seana Gavin and IDEA