For online procrastinators (which let’s face it, in lockdown, is all of us) TikTok is the ideal virtual playground. The For You Page (FYP) enables mindless scrolling without the effort of finding good accounts to follow. And the platform’s uber quick style of sixty-second videos mean in under five minutes, you can unveil rabbit holes of everything from farming TikTok (young farmers playing with their favourite sheep) to private school TikTok (cringingly addictive recounts of boarding school dramas from the junior one per cent).

But underneath all of those fantastical aesthetics and super niche subcultures, the app has a darker side too. One that threatens the comedic oasis that has captured the attention of over 800 million monthly users. TikTok is increasingly filled with weight loss content; ab workouts and ‘what I eat in a day’ videos make up a hefty section of the FYP, although of course the algorithm also means that the more you watch, the more you will be recommended. While at first irritating, the initial run of videos a user might say vary from a pushy diet culture PSA to accessible and easy at home workout videos; but scroll a few seconds further and it isn’t hard to find a worrying chasm of pro-anorexia content.

While the content itself is disturbing, this issue, it should be noted, isn’t unique to TikTok. Triggering content has existed on the social media platform du jour for many years, whether it’s Tumblr or Instagram. What makes TikTok stand out, however, is that (unlike Instagram’s explore page) the FYP functions as a landing page. From the moment a user opens the app, they’re presented with a deluge of stranger created content based on algorithms, before that of their actively followed accounts. It seems only necessary to linger on a video and the next three to four suggestions on the FYP (or when you next open up the app) will follow a similar theme, making it easy to get trapped in cycles of triggering content.

TikTok’s community guidelines state that there is, at least in theory, a blanket ban “content that supports pro-ana or other dangerous behaviour to lose weight” with the exception of content that “provides support, resources, or coping mechanisms.” #Eatingdisorder has 23.7 million views, but the hashtag is equally weighted with recovery and awareness videos, content which TikTok is eager not to discourage in fear of creating barriers around discussion of mental health. This inevitably causes a bit of a content minefield. What is helpful to some may be triggering to others, while other videos outwardly promote or condone the behaviours that users may be scrolling the tag to deal with and address in the first place.

Not only are eating disorder and anorexia hashtags frequently used, but there is also a plethora of misspelt variations of the words. Though typos are an easy mistake to make, #Anorexie, in particular, has 17.2 million views and the content using the hashtag tends to be more triggering than that of #anorexia, suggesting an intentional attempt to disguise the content from TikTok’s moderation. And with UK eating disorder charity BEAT reporting a 30% increase in demand for their eating disorder support services during lockdown, the prospect of the TikTok algorithms actively presenting vulnerable young people endless triggering content is increasingly alarming.

18-year-old Grace has struggled with an eating disorder for six years and is currently in recovery. The Washington-based teenager began engaging with eating-disorder related TikTok’s to support those in similar situations. “I’ll sometimes comment on eating disorder related posts trying to be encouraging,” she says, but the interaction meant her FYP quickly filled with pro-anorexia content. “I make an effort never to like anything related to them,” says Grace, “seeing stuff like that on a platform I go on to watch funny stuff can be annoying or just flat out triggering and upsetting.”

Along with triggering pro-ana content TikTok is increasingly also home to a serious thread of misinformation around health and diet, with teenagers encouraging the use of laxatives, abuse of ADHD medicine and replacing meals with iced coffee to achieve the perfect ‘skinny’. One ‘eating disorder check’ sound effect has over 1,500 videos using it and despite its primarily ironic use the ‘so you think I’m skinny’ sound effect has over 85,000 uses, not all of them as tongue-in-cheek as you might expect.

It was these kind of videos which led 19-year-old Joely Pendleton to delete the app altogether. A self-confessed TikTok addict, Liverpool-based Joely originally downloaded TikTok, like many of us, for funny content, but soon dark humour turned to explicit content about self-harm and eating disorders. “It started to show me the pro-eating disorder content, it was the ‘eating disorder check’ sound effect showing people wrapping their hands around their thighs. I consistently ignored it, but it kept showing up and then they started advertising apps for intermittent fasting and that’s when I deleted it,” she says.

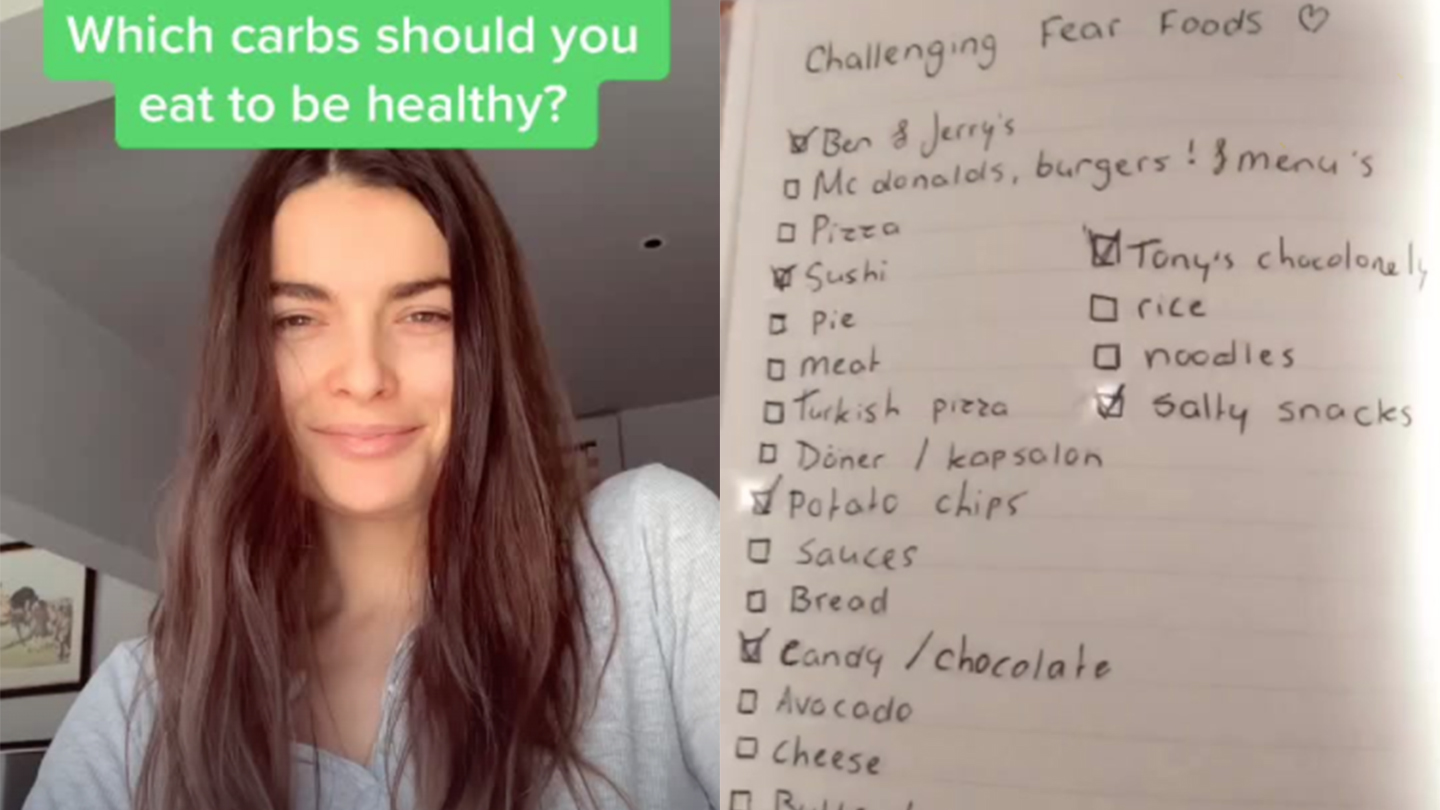

But just as the triggering content is increasing, so too are a growing army of users trying to combat it. TikTok users like Jennifer Medhurst, known online by her handle @theimperfectnutritionist, is using her platform to encourage healthy relationships with food. A BANT certified nutritionist who took to TikTok in rebuke of Instagram’s ultra-curated, equally triggering aesthetic, Jennifer discovered the former platform had more space for conversation and dialogue. Now, her healthy meal ideas and myth-busting videos have amassed 14,600 followers in just over two months. “Eating disorder content is not unique to TikTok. I just think it’s more exposed,” says Jennifer, “They need to make the algorithm not work so well for certain bits of content.” The nutritionist is optimistic though. “My account is growing incredibly quickly and I think that’s because there is a lack of information out there,” she says, “and there’s clearly a desire for that information.” As the app becomes more popular with older age-groups Jennifer hopes the information around diet will filter itself, and gradually become less insidious.

And of course, living alongside the potentially triggering content there is also a thriving eating disorder recovery community on TikTok. Users create specific recovery accounts, which they use to hold themselves accountable to their progress and encourage one another whenever they might be struggling. One video with over 31.5k likes shows a girl eating a satsuma. The caption reads: “I ate today because of you guys. FOR you guys. I owe you all so much. Thank you.”

Nutritional Therapist Jenny Tomei uses the eating disorder hashtags (and their various misspellings) on her own videos, hoping to break up potentially triggering content with advice and non-glamourised truths about the serious effects of eating disorders. Jenny, a recovered anorexic herself, has become integrated into the recovery community on the app. “I’ve got this little community going,” she says. “I’ve really connected with them and given them a lot of my time.” With lockdown restricting access to therapists and support services, Jenny’s advice is taking on added importance to these users. “They’re all relapsing and putting their heads into TikTok and seeing ‘ab checks’ and ‘1,200 calorie what I eat in a day’ videos,” she says. “I try my best to drown out the masses but no I don’t think it’s enough as there’s too much of it [pro-anorexia content] out there.”

TikTok, for their part, claim to constantly be reviewing and removing videos, taking into consideration the account, hashtags and videos themselves to draw the line between triggering content and that which may assist user’s recovery. The app employs both human and computer moderation systems; you can also hold down a video to select ‘not interested’ and remove similar content from your feed, a surprisingly undiscovered feature of the app.

“Keeping our community safe is a top priority for TikTok, and we care deeply about the wellbeing of our users,” a spokesperson for TikTok said. “For some, TikTok provides an opportunity to share their experience of living with or recovering from an eating disorder and expression of this nature is permitted within the boundaries of our Community Guidelines. Any content or account that seeks to promote or glorify eating disorders is a violation of our Community Guidelines and will be removed.”

TikTok’s algorithms are the subject of much mystery and admiration across the internet but their effectiveness becomes counterintuitive when applied to triggering content. The social media platform may well be conscious of the precarious balance of self-expression and safeguarding it has to enforce, particularly with a user base predominantly made up of under 25s, but regardless, it needs to find a way for users like Joely to safely and happily browse the FYP. Data suggests TikTok has recently claimed the crown as the most downloaded app in the world, but with success comes responsibility. The company now has a rare opportunity to lead the way in building apps to safeguard mental health for young people. Let’s hope they take it.