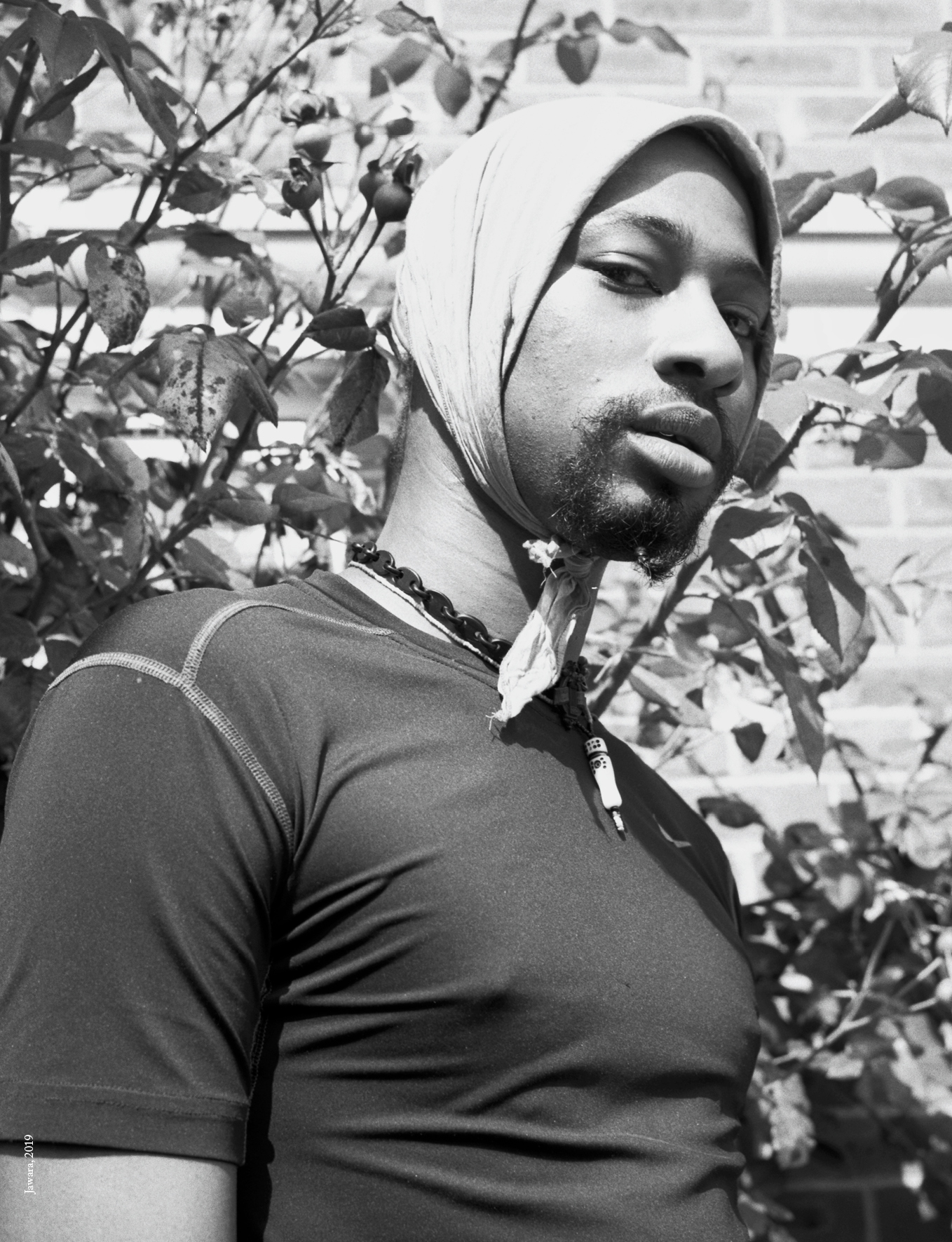

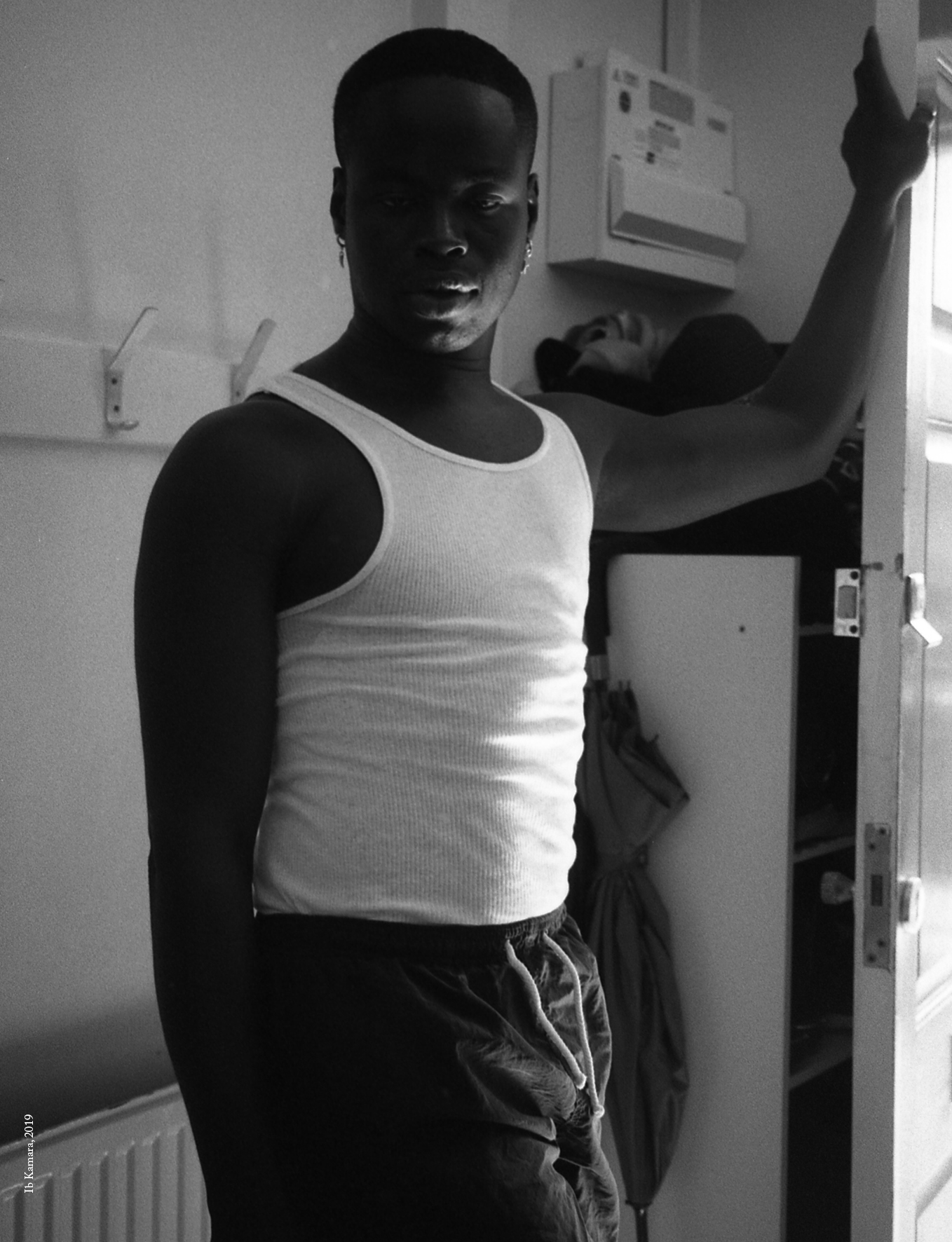

Boy.Brother.Friend first appeared on our radars back in 2017 as a limited edition zine by London-based stylist KK Obi, produced in collaboration with concept store LN-CC and Nataal magazine. A visual paean to the creative community KK’s long been part of, its pages were filled with dreamy, intimate portraits of figures including Kareem Reid, i-D’s Ibrahim Kamara, and Femi Adeyemi — the young black men at the scene’s heart.

Now, Boy.Brother.Friend returns with a broadened scope, this time as a fully-fledged biannual publication and digital platform. “An invitation to cross-examine intersectionality, male identities and transnational cultures in the world today,” it steps beyond individual focus to explore meanings and understandings of black identity through fashion, photography, essays, theory and much more.

With ‘Discipline’ as its banner theme, it’s subdivided into five chapters: ‘Control’, ‘Community’, ‘Environment’, ‘Family’ and ‘Post-Visibility’. Across each, you’ll find imagery from, to name but a few, Algerian-born artist Mohamed Bourouissa, Rafael Pavarotti and Liz Johnson Artur, whose photographs of friends gearing up for Notting Hill Carnival you can see here. You’ll find Shakeena Johnson’s biting monologue on the Don Juanism of a man she’s loved; pictures from Alfredo Jaar’s sobering Rwanda Rwanda series; Campbell Addy’s portraits of the young creatives of colour that give London it’s global reputation.

It’s about reclaiming the means by which these identities are documented. “There really aren’t many publications that do,” says KK. “It’s really about us having something in a physical form that you’re able to archive and which lasts, hopefully forever.” With most of the researchers that write on Africa or the diaspora of black nations tending to be white, explains Emmanuel Balogun, Boy.Brother.Friend’s editorial director, “there’s always a need to own one’s own narrative,” he says, “so it was important for us to be the writers, narrators and conceptualisers of our own culture and our friends’ cultures.”

To hear more about Boy.Brother.Friend’s latest chapter, we caught up with KK and Emmanuel.

What’s Boy.Brother.Friend’s mission statement?

Emmanuel: Community is really the focus. We want to provide a space to celebrate our friends, to define ourselves on our own terms. It also tries to connect experiences, looking at transnational cultures. If you go to places like Nigeria, for example, you can see how it’s so receptive of the cultures of America, the UK, or any kind of colonial, capitalist power. We wanted to connect and define these cultures that are constantly shifting.

KK: It’s also about being able to have conversations that people forget to have, are afraid to have, or simply don’t have access to contexts in which they can have them — that’s also a key part of it.

Emmanuel: I used to work as a stylist years ago, and KK and I would always have this conversation about why there wasn’t a truly fab black magazine. And there still isn’t one, really. Not that it’s what we set out to do, but I feel that this could be it in terms of representing black cultures in a way that’s truly diverse — artistically driven, conceptual, creative, sexy, all without feeling fetishistic or tokenistic. The goal is to really change the way people view these cultures.

Yes, one of the most interesting things is the diversity of approaches. It’s not just a glossy fashion magazine; it’s not just an academic journal. There are also personal essays, data research, contemporary art content.

Emmanuel: When KK started it as a zine, it was focused on portraits and their accompanying confessionals. But, given our different backgrounds — KK’s a stylist and creative director, and I’m a researcher and writer, and have worked in spaces from international development to contemporary art — this was a way to blur all these different worlds together. We felt that the person that cares about Africa is curious — they want to read affirmation, they want to hear about the history of scholars they’ve never heard of.

KK: From my experience of living in Africa, I know that creative industries have always thrived. Music is huge, and contemporary art, especially now, is a market that’s growing exponentially. Taking all of this into consideration, it would have been silly not to broaden the conversation beyond a particular genre or creative medium, especially if we’re talking about the diaspora.

Emmanuel: And I don’t think the world needs another glossy magazine that doesn’t really critique or, you know, inform. People on the continent read a lot: they’re very critical, they’re constantly faced with political conundrums in their daily lives, dealing with issues like sustainable development goals, and constantly being force-fed a rhetoric of debt-for-development. It would be insensitive to not look at our culture and all the driving forces within it. As it would be not to look at what we need to prioritise, things like history, intersectionality, and the psychosocial structures that we deal with every day, which have profound implications on how people act and present themselves.

How is that illustrated across the publication’s pages?

Emmanuel: I’d say Jazz Grant‘s piece is a good example, it’s directly about the environment. West Africa has extremely high rising sea levels, and it’s a place that receives all of the byproducts of the environmental neglect happening beyond the continent. There’s also Dan Adeyemi‘s piece about deep sea internet cables and the cultural flows they illustrate. Even with foreign direct investment, cities like Lagos, Accra, Kinshasa and Cape Town are all still defined by their connections to other places around the world. And then peppered throughout are theoretical affirmations and quotes from bell hooks, Cornel West and Stuart Hall. Then there are interviews with Damson Idris and Kenneth Ize, which are more personal: Damson’s, for example, looks at his relationship with gender and masculinity. There’s also ‘Cartographies of the black male psyche’, a deep-dive on mental health and health institutions.

The issue’s title theme is ‘discipline’. How did you settle on that?

Emmanuel: I was born and raised here, and KK was born in Nigeria, but most of his life has been in the UK. For both of us, there are different ways that we’ve had to act, or things we’ve had to adhere to — definitions of what being an African man is, or being a good child. Conditioning and self-conditioning play such formative roles in shaping masculinity, so we really wanted to look at discipline in that respect, thinking about how we control ourselves, and the systems that are in place to punish us. Sometimes that can be family. Other times, the environment, or the rules of certain spaces that we exist in. That’s what inspired the title of one of the issue’s chapters, ‘post-visibility’. Rather than looking at visibility as something that we’re trying to earn or gain in a particular space, it envisages the creation of our own area of visibility where we can see ourselves.

KK: For me, it was also about looking at all the amazing people within our community that do incredible things. Through my work, I always want to contextualise what’s going on right now, while also looking at themes that are specific to diaspora communities — family, for example. It’s such a poignant subject, and it’s something that we’ll probably have to revisit again and again, because it’s such an undiscussed aspect of life in the diaspora. And then we also wanted to look at elements of control that pertain to all the things that are going on right now, looking at how certain people feel marginalised in certain ways, or our relationship with the environment.

What do you hope people will take from the publication?

Emmanuel: That the audience can see themselves in the pages. It was important to me to include Oluwasegun Romeo Oriogun’s poem “Burnt Men”, which is basically about the issue of men who have tyres thrown over their heads to burn if they’re found out to be homosexual in Nigeria. It was important to have words that people can read and feel like it’s telling their story. They’re living in a part of the world where they’re alone, where they have no like-minded people they can talk to. Whatever sexuality or gender they identify as, we just want them to feel that we stand with them, and that this publication is a testament to their lives.

Boy.Brother.Friend is available to purchase here.

Credits

Photography unless otherwise credited Liz Johnson Artur

Courtesy of Boy.Brother.Friend