“I think when you come from a Jehovah’s Witness family; you’re a young, black man; a young, working-class black man, in fact, and you’re queer and you’ve been a sex worker, there’s already so much that people will just not be familiar with at all.”

Rainbow Milk — the debut novel of Paul Mendez — isn’t a story told a hundred times over. Opening in the 1950s from the perspective of a Jamaican ex-boxer named Norman, we peek behind the twitching net curtains of post-war Britain’s hidebound cul-de-sacs to find little more than hostility and violence. Leaving Jamaica for the Black Country and its promise of employment, the racism Norman faces submerges his world into darkness. The plumes of thick toxic smoke that billow from the region’s many factory chimneys become literal and metaphorical foils to his pursuit of happiness, beckoning the steep decline in his physical and mental health. “Like Bedasse did sing,” Norman thinks to himself, his son rested upon his chest, “depression gwine guh kill me dead.”

Then, we’re in Brixton. It’s 2002, and Jesse, the story’s protagonist, is on his way to have sex with a client he’s met on Gaydar. Since leaving the West Midlands and his Jehovah’s Witness family, the gay desire that bubbled beneath the surface throughout his teens has boiled over into train station toilets, gay bars and the bedrooms of older men. Finding sex work as a way of keeping his head above water, Jesse — starved of familial and romantic affection — also looks to find moments of tenderness amongst these fraught sexual transactions. Instead, he mostly finds huge chasms that separate him from the wealthy white men he visits. The racism of Norman’s generation may have mutated in the 50 years that have passed, but it still remains constant and insidious.

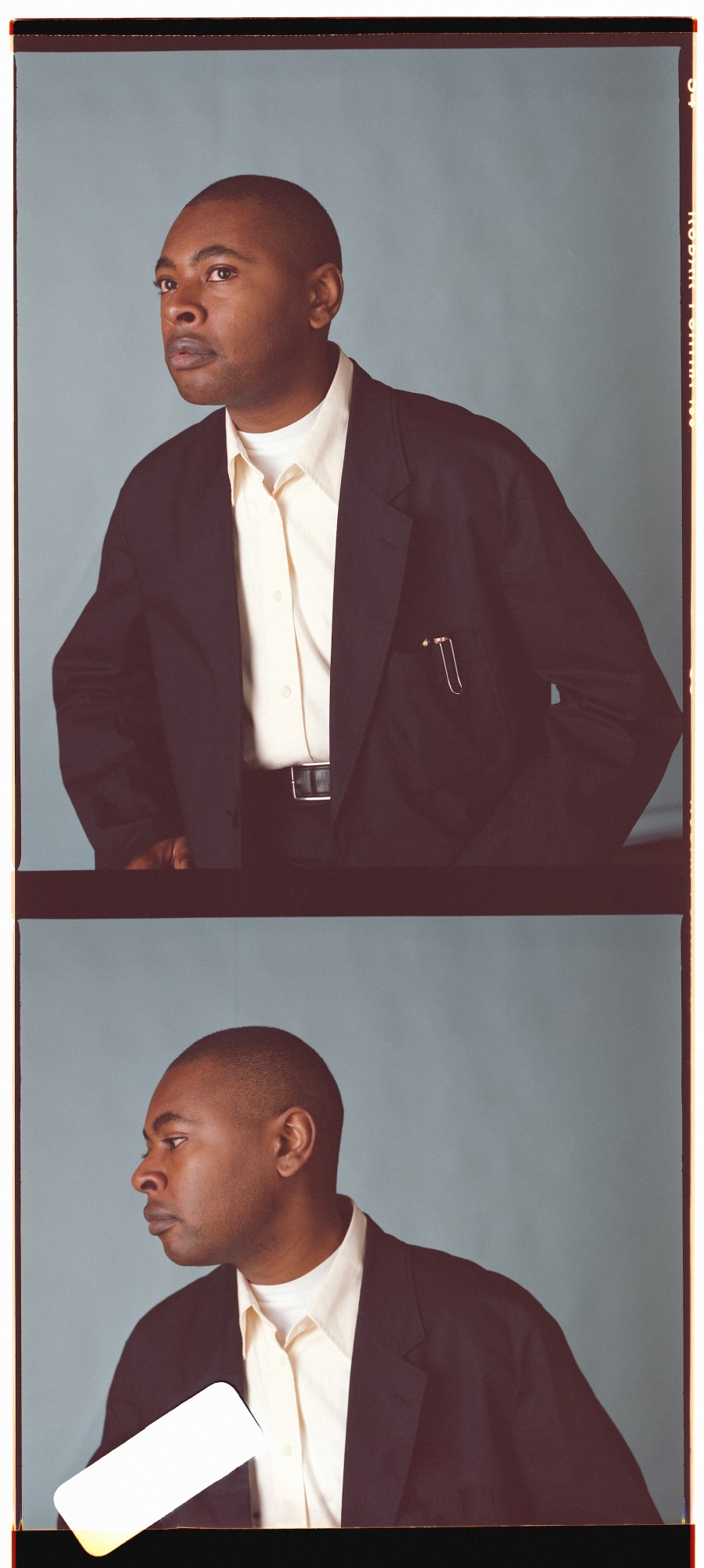

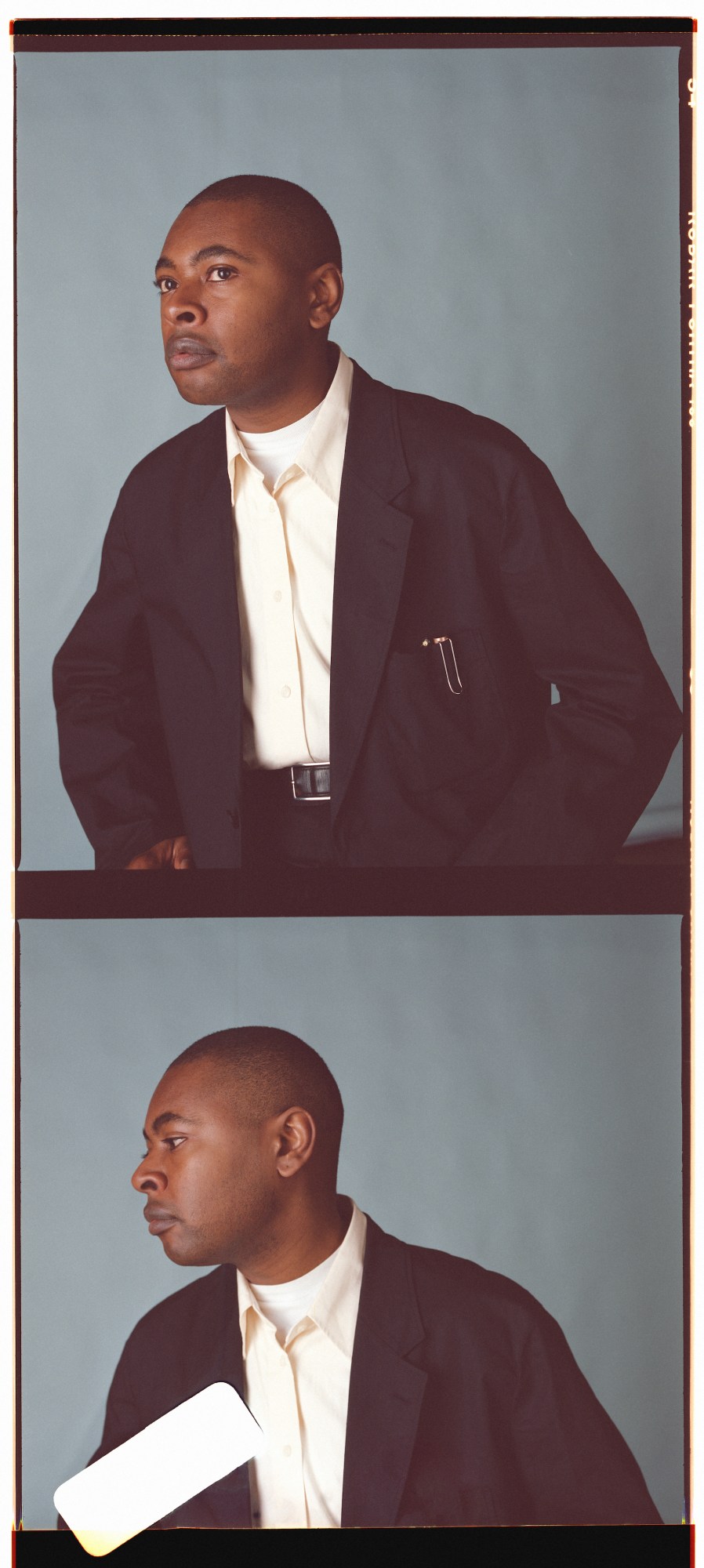

For Paul, who left his family of Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Black Country behind at 22, writing this book meant reaching into 15 years worth of sporadic journaling and piecing it together into a story that resembled something of his remarkable life. Working a number of different jobs including acting, writing and restaurant gigs in the past few years, it was only recently, when a friend he met at a party joined a new publishing house, that he decided to submit a manuscript that would eventually become Rainbow Milk, out next week. On a rainy, pre-lockdown Wednesday afternoon in a small cafe off Baker Street, Paul discussed with us the making of this triumphant debut novel.

This is your first novel. Tell us a bit about your background, when you began writing and where your story fits into the narrative of Rainbow Milk.

I’m from the West Midlands, the Black Country. I was born in 1982 to a very working class, second-generation Jamaican immigrant family. We lived on a majority white, working class estate and I was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness. I don’t know if you know much about them but they believe the end of the world is imminent and that we should eschew any plans for our lives in this world in favour of preaching the good news, as they call it, on a full-time basis, trying to draw everyone into the religion before Armageddon happens and wipes everything else away — all the evil.

That was my life until I was 17. I showed a lot of promise at school but didn’t ever really take any academic ambitions seriously. I was kicked out of my accommodation when I was 17 for no reason really. I had lied about being drunk and they took it really seriously and excluded me. I wasn’t allowed to associate with anyone I had grown up with. I moved to London when I was 22 to start acting, and became a sex worker, so that I could pay my fees, basically, and have a life. Very soon everything unravelled — I quit my course but stayed in London and started writing. For the past 15 years or so, I’ve been working in restaurants, doing bits of journalism wherever I could and writing, mostly autobiographical stuff which became sort of a memoir.

It was never calculated as a book, but when I heard my friend Sharmaine Lovegrove was becoming a publisher at Little, Brown, I put together a 300-page manuscript based on small fragments that I’ve been collecting over a period of 15 years. I cut it together in a style that could be judged as a narrative and was given the opportunity to write a novel.

So in the process of turning this into a novel, how did you know when to veer into a fictionalised version of what happened, and when to be authentic to what actually happened?

There’s so much that people will not be familiar with about this story. When was the last time you read a novel set in the Black Country, for example? For me personally, I’ve always written for catharsis as much as anything else. You can tell when I’m just sort of bleeding and trying to heal through writing. Experienced readers will be able to feel the rawness in the words. I’ve always written in first person, so one of the ways in which I was able to distance myself from it was writing in third person. My manuscript was five months late. I handed it in in January last year and then two days later emailed my publisher and said ‘Stop now, I want to re-write it in third person’ and I did, in two months, from scratch.

The other way I was able to change things was to make the father figure character an adoptive father. I created the character of Graham [Jesse’s father] and that was really the first, from scratch, character I had ever created. Installing him as an adoptive father, he didn’t even need to be that different from my own father, but because he is white, that completely changed everything and it gave the book a completely different perspective in terms of fatherhood, in terms of Jessie’s tastes, his sexuality and the people that he went for.

Actually, the first character I created was Norman. He is roughly based on my grandfather who I never knew and who my dad never knew either. I only knew a few sketchy things about him, and I had done a bit of acting so I thought ‘how am I going to get this voice?’ and I improvised him. He went blind so I blindfolded myself in my bedroom and then walked around my house and just recorded myself speaking in Jamaican patois, talking about what life might have been like for him and then transcribed that into something that I could use.

It’s interesting that Norman was the first character you conceived, because you read that first section of the book and assume it’s going to intersect at some point in the story, and practically never does. It was essentially a prologue to Jesse’s story. Was that structuring a conscious decision?

No, it happened by accident, just having these two narratives, Jessie’s and Norman’s, and I realised that I could tie the two together. That decision, I’ll be honest, happened quite late on in the process. I was thinking of slave narratives and neo-slave narratives, like the history of Mary Prince, for example, a slave in Antigua and Bermuda who was viciously abused by her slave owners. But she was taught to read by their daughter and when they decided they were going to come to England she begged them to take her.

By then it was the early 1830s and a law had been passed that slaves weren’t slaves anymore on English soil. She managed to find a new benefactor who she told her story to and he published it as a book, The History of Mary Prince. It had an introduction by him saying, ‘This is why we need to abolish slavery, look! She’s really articulate, she’s got a heart of gold, she’s very clever, she’s got great potential.’ But he was this upper-middle class gentleman, the inference being that nobody would pay attention to her story if it wasn’t for him legitimising it.

We’re in this sort of post-Windrush where voices are being forgotten, and my generation is forgetting what Norman’s generation lived through, and I wanted him to legitimise Jesse’s story. I wanted him to be able to give his account of what life was like for Jamaican immigrants in the 1950s and I wanted Jesse, who would never know him, who would never meet him, to get the benefit — or for the reader to get the benefit — of those stories.

How much did you want these characters to resemble your family and friends?

I’ve written a lot, for myself, about my relationship with my mother. But she is still young, she’s still alive and married to my father. She’s still my mother. I tried to look at other writers, like James Baldwin, for clues as to how I could treat living people in a sort of semi-autobiographical, fictional space. I realised I couldn’t have much of her in the book, but I could present a character, very similar to her perhaps, that treated Jesse in a very similar way to how I was treated. The book needs to be about Jesse and about him growing up and realising who he is and who he can trust. I didn’t want it to be about my family. My parents aren’t material people, I don’t know if they would read the book or not. I’d like to think that they would think that I’ve looked at the things that happened to Black people generally and to Black British people of the second generation rather than just picking them out as individuals. The last thing I want to do is open my parents up to the glare of my rendition.

There’s a line towards the very end where Jesse is recalling his mother holding a knife and saying something like ‘I wish I could just stick this in you’. To the very last page, Jesse withholds certain information that is so traumatic. For you, how therapeutic was it to exorcise these memories? Do you feel a sense of relief?

I mean, I’ve been through a hell of a lot more than what’s in Rainbow Milk. I don’t know if it does really… it helps to write things down and to realise what’s happened, why, how you’ve dealt with it and how you’re continuing to be affected by it. And I think all of us, everyday, experience memories and sensations from the past based on being triggered. I’ve not put anything in Rainbow Milk that I need to keep for myself or that is unresolved.

Having gone through the experience of writing, what does it make you want to pursue in your next book? Do you want to veer away from more traumatic, tragic fiction and write something a bit softer or not?

I’m reading a lot of Toni Morrison at the moment and she is such a sadist when it comes to her characters. She makes the worst things happen to her characters all the way through her books and that’s how people’s lives are. Maybe not necessarily in London, but where I’m from, and especially the period I’m interested in writing in, people’s lives were fucking hard. Whether it’s the council threatening to repossess their house, domestic abuse in a marriage or sexual assault happening in terms of parent and child relationships, pollution, lack of food, poverty.

I’m interested in writing for working-class British people, like Toni Morrison has for Black working-class African-Americans. I love what she does in terms of taking an extraordinary community in a small town in the middle of nowhere and making that a universe. She can write a 300 or 400 page book just on that and yet it’s just as rich as anything else I’ve ever read. What I’ve done with Rainbow Milk merely opens me up, as an introduction, to the things that I want to focus on as a writer. I want to write about the Black Country, I want to write about poverty, for people who don’t know that they have great potential, for whom London might as well be on the moon. I also want to write about sexuality and love within that very harsh environment.

Paul Mendez’s Rainbow Milk is on sale 23 April 2020.

Credits

Photography Amber Pinkerton