When we spoke with Copenhagen-based artist Esben Weile Kjær, the coronavirus pandemic — despite not reaching Europe yet — had already left him in a bit of a bind. With 2.5 tonnes of aluminium stage rigging intended for his upcoming solo show stranded in China, he’d quickly have to source an alternative producer in Denmark at short notice. Indeed, the COVID-19 crisis has hit the art world hard, with gallery and museum closures par for the course across the globe. Yet, though the field may currently be under siege, it doesn’t mean that there aren’t things to look forward to once it’s over.

Esben’s two-part exhibition, a collaboration between two of the Danish capital’s most esteemed contemporary art exhibition venues, is certainly among them. Known for his immersive performances like BURN! — in which he thrashed about stage-effect fire cannons in Copenhagen’s National Gallery in firefighter gear — his shows this summer mark the most ambitious expansion of his practice yet. Touching on themes of nightlife, power, youth, freedom and the production strategies of pop culture, the young artist interrogates and levels the hierarchies that separate sub and mainstream culture, authority and subject, the watcher and the watched.

The aforementioned metal rigging is the central focus of Power Play, due to open at Gammel Strand on May 2nd. Installed as rollercoaster-like forms in the venue’s main hall, they’re activated by sound, moving headlights and wind machines in what Esben describes as a “light ballet or a performance by technology”. Once a week, they’ll also be joined by a troupe of performers, among them Esben himself, clad in fragments of military and public authority gear, playing out subcultural dress tactics. “I come from a punk background myself, and I’ve always been excited by how different youth cultures have taken symbols and used them against their initial intent,” he explains. “For example, a police jacket on a person with green hair will create a visual message of subversion, rather than one of support for such institutions of power.”

These visual metaphors are further explored in Hardcore Freedom, a blockbuster installation at Copenhagen Contemporary due to open on August 14th. In a space that blurs the boundaries between nightclub, art institution, and church — think a stained glass window, pole dancers and a giant red-eyed Tinkerbell floating above the room — Esben explores the relationship between rebellion, partying and the manufactured sense of freedom that both entail.

We chatted with the Danish artist about how pop music informs his practice, how Ibiza’s nightclubs can be considered museums, and whether subcultures still exist today.

Where did you begin your research for the two shows? It seems like quite a multifaceted body of work…

It’s difficult to state exactly. I started with Hardcore Freedom, the show at Copenhagen Contemporary opening in August. I’d had ongoing conversations with Ida Maj Ludvigsen, the show’s curator, and Marie Nipper, the institution’s director, so we decided to work on the idea together. While working on that, Power Play, the show at Gammel Strand curated by Anna Kielgast, came into the picture. And I was also working with another artist, Freja Sofie Kirk. We went to Ibiza last summer to work on a video piece at Privilege, the world’s biggest nightclub, called ‘Industries of Freedom’, which will premiere in Power Play.

What does it entail?

It follows this troupe of performers called the Ultra Angels, who work at Privilege throughout the summer season. We were DMing on Instagram and asked if we could follow them for the ten days we were there.

What’s so interesting about them is how their faces are used by the club. If you look at how Ibiza was back in the 80s, it was known for its free-spiritedness, and it was nowhere near as industrialised as it is now, with superclubs that host up to 10,000 people every night. The main draw for the clubs that did exist was the music, the DJs. Now, though, the main attractions are groups like Ultra Angels. They basically serve as the club’s PR strategy and are really famous within the Ibiza ecosystem.

The film itself is really about trying to understand the architecture of the world’s biggest nightclub, and how the performers interact with it. They’re suspended from the ceiling on wires as if they’re flying, and somehow, they seem to become part of the building. They’re wearing these really futuristic, sexed-up outfits that verge on fetish gear, but they blend in with the light show so well that their bodies almost melt into the architecture of the club, to the extent that you almost forget they’re there. Their bodies become architectural material at the same level as, say, the lighting, or decorative sculpture. Ultimately, we were really looking to understand and cast light on the complexity of experience economies like nightclubs, but from the perspective of those that work within them.

So their bodies are commodified by the club?

Yes, in the sense that every day they’d walk along the beachfront, where everyone lies about when hungover, and everyone would approach them to have their picture taken. It really makes you realise how they’re viewed as commodities. But there’s real artistic value in what they do. I don’t believe that performance as an artistic medium began in the 60s, as canonical art history would have us believe. It goes back much further, to Dada and burlesque — both of which are rooted in cabaret and the club. It was then taken from there into the exhibition space, which is why I think we should look at performers like the Ultra Angels seriously, rather than as something inferior. It can be read as ‘the new burlesque’, in a way.

Why do you think that is particularly well attested in Ibiza today, compared to other clubbing capitals?

Last year, I was reading this article about London and how many of the big commercial clubs are closing because people are partying less. I was like, ‘What? Really?’ Apparently, people are spending more time working on their fitness and dating through apps rather than going to clubs to meet people, and there’s also been a flourishing of a more DIY, illegal scene, too. I started becoming interested in this idea of the club as a relic, or museum, and I think that if you want to look at it from that perspective, then Ibiza is such an important place. It’s been a mecca since the birth of commercial electronic music and has always treated music as pop culture. And I’ve always been more interested in mass culture than underground, more into EDM than techno, for example. I’ve always approached my practice through pop music, and places like big festivals — or entire islands, in Ibiza’s case — have always interested me. They’re not just spaces within cities, they’re entire areas given up to a specific way of consuming culture.

Also, the world’s biggest nightclub is there. It’s called Privilege! And it’s in an old shopping mall! It just felt like a gift. There’s just so much to observe and understand there. There’s nothing to add in terms of image production or performativity. So it was more a case of approaching that material from my aesthetic and sociopolitical perspective as a visual artist.

Hardcore Freedom is said to treat the Western idea of youth and freedom. What is that idea exactly? And how do you challenge it?

I think our understanding of freedom in the West is very connected to the idea of youth. But at the same, that freedom’s still very produced. Mark Fisher outlines it well in his discussion of nightclubs in the 90s. They were places where you could experience this feeling of freedom, but it was still manufactured and commodified. You still have to go to work Monday to Friday to earn money that you can then spend in these institutions to obtain that feeling. It’s still so tied to the idea of consumption. I don’t have an answer to that dilemma, but I just really wanted to explore and understand the prevalent visual narratives of our time, as well as how pop culture produces itself.

Also, the concept of ‘youth’ as we understand is still quite recent. It only came to be in the 50s, really — before then you were a child and then an adult. Since that awakening, the borders of youth have only continued to expand — we now talk about how your thirties are your new twenties, and it feels like youth is now more of a perspective you adopt towards life, rather than a definite period of time within it. You choose how long you want to be ‘young’. ‘Youth’ and ‘freedom’ have therefore become synonymous as ways to hide from specific societal norms that want us to ‘grow up’ and to take responsibility

The codes of subcultural identities form a large part of the show. What are your thoughts on the current status of subcultures?

I don’t believe that subcultures exist any more. To me, they died with social media. Also, visual languages develop and change so fast today, so the idea of subcultures are a bit outdated. But the reason I think it’s still interesting to look at is that they offer a way to understand our current visual languages with regard to what they once were. If the anarchist symbol is just a print on a T-shirt sold at WEEKDAY, does it even mean anything? What even makes for a ‘progressive’ identity anymore? That’s probably why I’m so drawn to EDM, as it’s the opposite of any supposed ‘subculture’. I often think that pop culture may have become the new counterculture in certain respects. Like, when I listen to Calvin Harris or Avicii, I can listen to it as super progressive, while also acknowledging how commercial it is. And perhaps being able to straddle that duality is the most progressive or subversive state you can occupy today.

Power Play at GL Strand, May 2 – June 7 2020. Hardcore Freedom at Copenhagen Contemporary, August 14 – October 18 2020

Credits

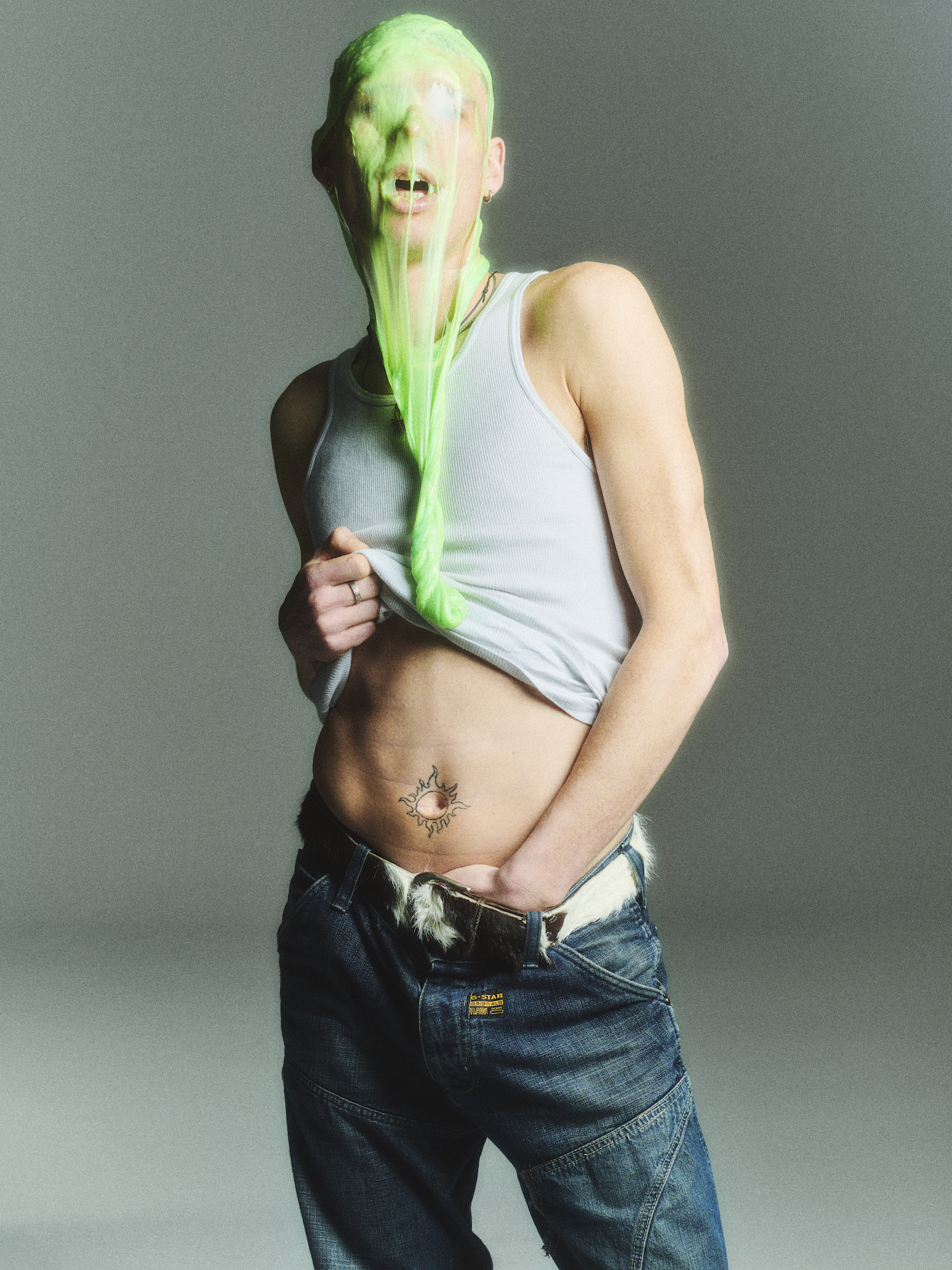

Photography Philip Messman