The story of making it as a creative in London is one you’ve probably heard, often starting in the hallowed halls of one of the city’s esteemed art schools. To this day, the success stories of working-class creatives like Alexander McQueen or John Galliano are still touted as emulatable, with London framed as a place that welcomes budding creatives taking their first steps toward stardom. The truth of the matter, however, is that this famed reputation is increasingly out of sync with the reality of pursuing a creative education in Britain today.

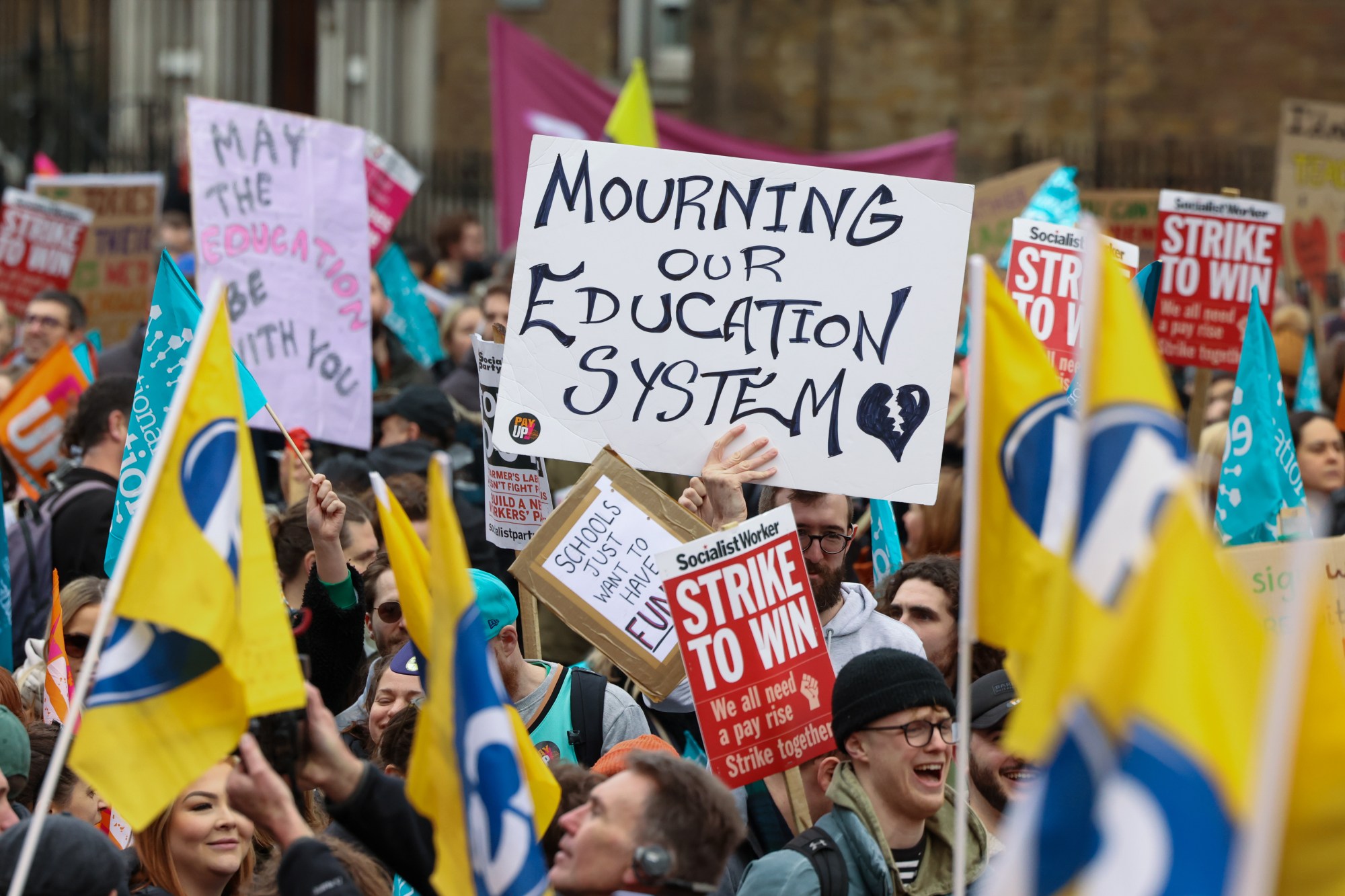

British arts education is in crisis, with the climate of opportunity it was known for in, say, the 90s having long since dissipated. In its place, we now see a hostile environment stoked by a conservative government that essentially perceives the pursuit of a creative education as a “low-value” pathway. With undergraduate degrees increasingly feeling like an endless debt subscription, masters barely financeable and the fierce competition for PhD funding increasingly limiting doctoral study to self-funded candidates, the grave situation at the UK’s arts education institutions is only worsening — all to the detriment of the country’s creative industries.

For a recent example, look no further than the Royal College of Art, a flagship among London’s creative educational institutions whose famous alumni include artists such as David Hockney and Frank Bowling, inventors like James Dyson and fashion designers like Zandra Rhodes, Erdem Moralıoğlu and Bianca Saunders. Under the leadership of Zowie Broach — a fashion practitioner and designer — the school’s fashion programme has established a reputation as one of the world’s most respected; a place where fashion designers and thinkers are encouraged to adopt an expansive, interdisciplinary and self-determined approach to discovering their own creative languages. Contrary to this ethos, last month, the RCA’s School of Design — the wider department that houses its fashion, textiles and product design programmes — announced their decision not to renew 21 associate lecturers on fixed-term contracts.

In the aftermath of the decision, the RCA branch of the University and College Union issued an open letter to the public, which stated that it “deeply damages the crucial role of the practitioner-lecturer at the RCA, which is also a core principle of art and design education.” Indeed, learning from artists and designers who actively participate in their respective industries, and pass on their learnings through their teaching practices, is a key draw for prospective students, offering a necessary bridge between academia and the industry.

“Anyone who has gone through creative education knows how vital the role of the practitioner-lecturer is,” Natassa Stamouli, Digital Editor of 1 Granary, says. “It connects theory with practice, and is more necessary than ever for art and fashion students who are truly struggling to gain employment, and to bridge the mental and practical gap between education and real life.”

Looking at the bigger picture, there are concerns that RCA’s decision could spark a trend elsewhere, particularly given the size and influence of the school. Speaking under condition of anonymity, a current RCA lecturer opines that “if successful in the School of Design, there are already attempts to roll this model of eliminating associate lecturers on smaller contracts out in every school of the RCA.” It’s a concern that draws attention to a damning fact — that, in the UK, arts education establishments are run from a business perspective, with their students, staff and other members seen as numbers on a profit maximisation spreadsheet. It’s a mentality that ultimately reduces tutors to disposable entities, failing to see that they are what motivates many students to enrol in the first place.

Granted, these decisions are only exacerbated by the UK government’s punishing approach to arts education. Just last week, Rishi Sunak announced intentions to cap the number of enrolments on what the government deems “lower value” undergraduate degree courses — i.e. courses where a proportionally lower number of degree holders go on to “professional employment”, a category that numerous arts and humanities degrees fall into, and stem available funding. While this decision wouldn’t affect those with the monetary privilege to independently finance their educations — most notably the international students who, in certain cases, pay fees reaching £20k per year — it would directly impact students from lower-income households, a group in which students of working class and BAME backgrounds are disproportionately highly represented. Funding cuts would essentially compel prospective students to be able to cover their fees and living costs independently, further widening the gulf between those who are and aren’t able to access a creative education in the UK.

These recently announced plans are but the tip of a far-reaching iceberg, and the deeper you dive, the more glaring the truth becomes: creative education has transformed into a commodity, with profit maximisation rather than, well, education as its end goal. It’s a fact that makes itself felt in the shortening of degree course lengths to increase the flow of students through schools’ halls; the higher classroom headcounts; the zero-hours contracts that are now standard practice for lecturers teaching on BA and MA degrees; the ever-steeper fees that fail to be met by an increase in the quality or scope of the education on offer.

Essentially, Britain’s creative educational institutions have branded their degrees as investment products, but have failed to make good on the promised returns. After all, students investing in a creative education often do so to learn directly from practising designers and artists. “Arts and fashion education are closely interlinked with the industry, and in today’s context, students can’t afford an education that won’t provide them with the tools that will help them to get employed and survive,” Natassa notes. “Disrespecting the educators is disrespecting the students, as it is directly affecting their future.”

“It’s clear that the school is at a breaking point, and isn’t functioning as it should be,” an anonymous current RCA student states. “Oftentimes, it has been a fight to get it to work for us,” with the students ultimately paying for these structural changes with their educational experiences, whether at RCA or at other UK schools. At a time when the country’s isolationist politics are making it a less and less appealing place for home and international students alike, the situation is one that risks culminating in the crumbling of the once-proud reputations of the UK’s creative education establishment, and in the country losing out on the creative talent that has shaped its past.

Addendum: Subsequent to the publication of this piece, a spokesperson from the Royal College of Art provided i-D with a statement regarding the situation at the College on 28 July 2023:

“The School of Design is ending 21 Fixed-term part-time contracts on their expected end date, as set out in the original letters of engagement. These roles are equivalent to 2.9 full-time staff, with some contracts being as small as under one day a month.

“Some of the staff with a contract expiring in the School of Design hold contracts in other areas of the RCA, and we are also encouraging those on Fixed Term contracts to apply for the new Permanent roles currently being advertised. We remain committed to decasualising our workforce by offering Permanent posts wherever possible, and no longer have any academic staff on zero-hours contracts.

“The changes relate only to the School of Design, and the School’s teaching and research needs going forwards. Practitioner-lecturers will always be an important part of the RCA academic offer, alongside research-active academics with postgraduate teaching qualifications, and industry-leading Guest Lecturers.”