Nothing keeps London from creating: not the pandemic, a catastrophic mini-budget, nor a cost of living crisis that has seen energy and rent prices soar. But it’s definitely become increasingly difficult to do so both for artists and for the people championing their work. Recently, young gallerists have taken it upon themselves to shake up the city’s art scene, and keep the capital buzzing, as major players flee a city that’s become increasingly hostile to do business in post-Brexit.

This new generation of contemporary spaces are redefining what it means to be a gallery in 2023: keeping overheads low by taking vacant office buildings off the hands of developers, sharing gallery space, and occupying obscure dwellings; they’re challenging the whiteness, privilege and hubris that has long defined the industry; and amplifying the voices of their local communities. More concerned with diversifying the local scene and giving everyone the chance to participate than profits, there’s the consensus that it is possible to run an equitable, sustainable business in the art world.

At GUTS Gallery, 26-year-old Ellie Pennick fights for more representation for people, like her, who come from working class backgrounds. She advocates for a complete rehaul of the art world so it does more than just pay lip service to diversity. While Grove’s Jacob Barnes and Morgane Wagner strive for longevity, supporting early-career artists, many of whom come from the neighbouring RCA, by guaranteeing a full-time income while they make their work.

Nearly two decades after the Young British Artists started their careers in Deptford, a new wave of curators, including Louis Chapple, are putting the area back on the London art map. His gallery, studio/chapple, celebrates sonic cultures while amplifying the local community in a space he shares with danuser & ramírez on a month on, month off basis. Zina Vieille and Nnamdi Obiekwe at V.O Curations collaborate with property developers to breathe new life into buildings that can sit empty for years, offering affordable studio space to emerging artists and helping them to put on some of their first shows. Meanwhile Oyinkansola Dada, owner of the roving Dada Gallery, celebrates Black artists in London without a permanent home.

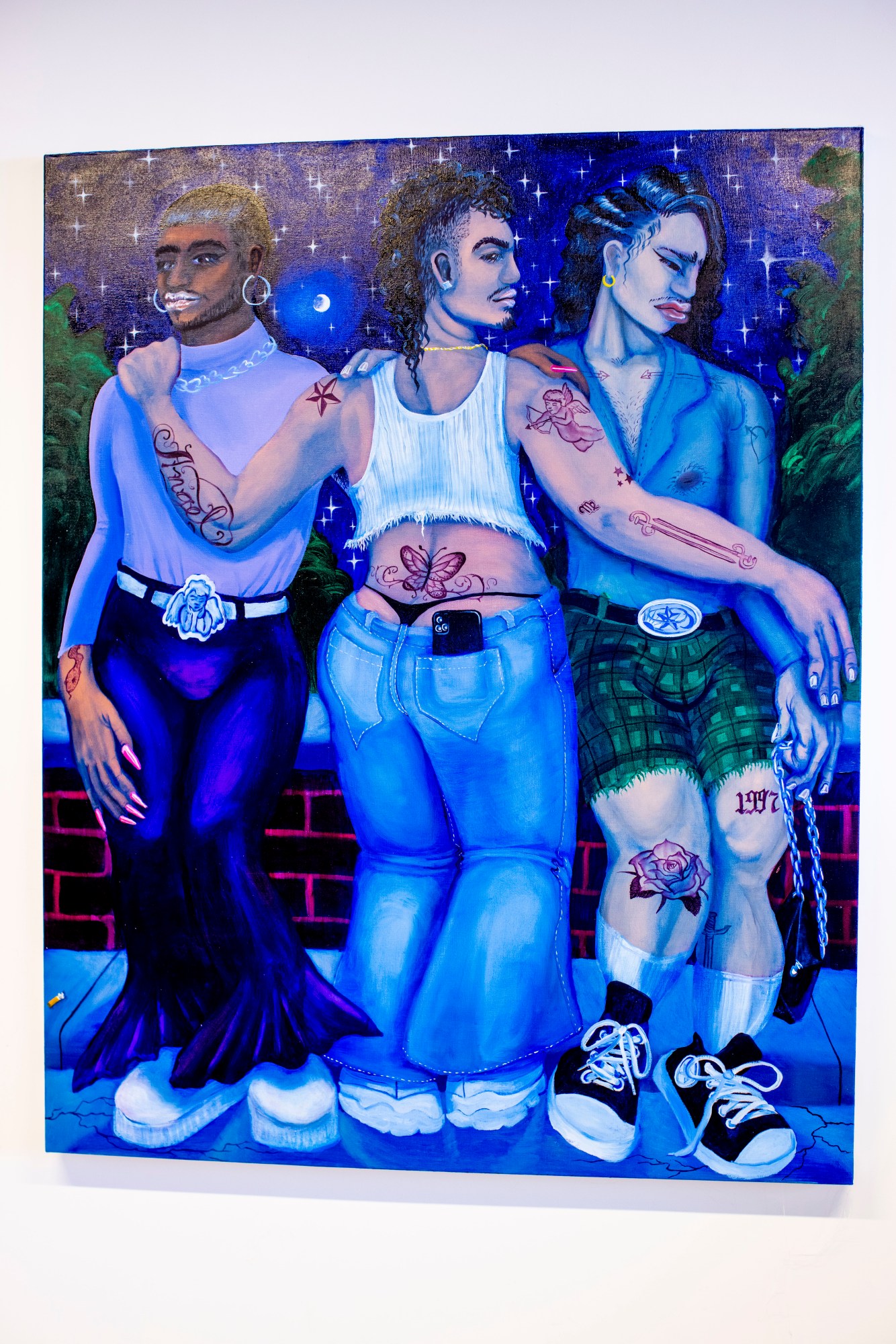

Others operate more traditionally, but take over unusual spaces. To minimise costs, Freddie Powell runs his pocket-sized gallery, Ginny on Frederick, in a former sandwich shop that has no toilet or running water. He praises his initial collector base for their brevity: “buying from this cowboy kid”, but it’s really down to his programming, which includes art that spans themes of sexuality, identity and politics. And it’s all very DIY down at Rose Easton’s eponymous gallery in Bethnal Green, where she champions work with either a subtle femme bias or a sculptural element in an industrial space, once owned by Wolfgang Tillmans, that she transforms time and time again. It’s all about the hustle — creating something beautiful in places that often shouldn’t work.

Here we speak to seven emerging gallerists, operating a successful business in the notoriously cutthroat London art market, while championing diversity, supporting emerging artists, rethinking space and celebrating community.

Ellie Pennick, Guts Gallery

Why is your gallery called Guts?

I wrote the name of what I wanted to call the gallery on the back of a betting slip at The Marquis of Granby. Guts, it’s like a gut feeling. Then there’s having the guts do something because when I was growing up I was always taught you had nothing to lose. But also it’s an acronym for Grafting Under Tory State.

How did Guts start?

I studied at Chelsea College of Art and then I got into the Royal College of Art to study sculpture. I was promised a bursary, but couldn’t get one. I took that to heart. I didn’t have a place to stay – it was a really stressful part of my life. One day, I walked into a pub called The Amersham Arms in New Cross, proper sticky floor, and I saw a sign that read: bartenders needed. I was like, ‘I need a job and have you got a room above the pub?’ He said they had a room and also an empty function room. I asked if I could use that to put on shows of my mates’ works. He said, ‘go on then.’

You started as a roving gallery before settling down in Clapton, how did you find this space?

This space I found on a website and the landlord liked what I was about so he gave me a really good deal. I think it was because of my accent. He asked what my parents did and I told him my dad was a milkman. He’s proper cockney, he’s lovely, proper sweet.

What is it like being in this industry as someone that has come from a working class background?

Really shit, they don’t make it easy. I calculated that 0.02% of working class gallerists are operating in the UK, that’s just mad. How can anything change if we don’t have people from a diverse range of backgrounds?

What needs to change?

The power dynamics for a start. I think how gallerists treat artists can be quite disgusting at times. I think diversity percentages need to change and treating staff fairly. There’s a lot of racism as well. Accessibility in general, people don’t always question whether somewhere is wheelchair accessible. People are ticking boxes and pretending to do things differently, but it’s all internal and there needs to be complete reform. We’re really behind compared to other industries.

In what ways do you support artists?

They call me ‘mama gallery dyke’, but I do go an extra mile. I’m best mates with them all, we take a lower percentage, we pay for absolutely everything as much as possible. We champion artists that deserve that space that have historically been denied it. We also don’t represent artists, we don’t sign contracts. Most artists are locked into contracts for three years and that’s just not a thing that we do, it’s on their terms. It doesn’t mean that they’re first but we recognise that they’re the centre because without artwork there are no galleries or auction houses. The reason we use champion was because ‘represent’ means speaking on behalf of somebody, but how can I speak on behalf of an artist with a different lived experience?

Louis Chapple, studio/chapple

Why open your gallery Deptford?

It is absolutely my favourite part of London, and has been before I had this space. I went to Goldsmiths, so I knew the area very well. Thinking about Deptford as a highly diverse and highly cultural hub in London, I feel like there’s a need for the shows that I put on to respond to the area that we’re in. For example, the sound piece that’s playing out of Bill Daggs’ sculpture is called “Outside Charms”. Charms was a club in Deptford — I think it was a Caribbean club, they had a lot of dancehall nights — but when Marvin Gaye was living in London for a bit, he was a regular there as well. That was in the 80s. It’s evolved with the sonic cultures that have existed in south east London. I’m always trying to have some element in the show that brings Deptford in or goes out into Deptford.

That’s important when a lot of art galleries can be the first to gentrify neighbourhoods.

I think you have to be hyper-aware of your position coming into the space and a lot of the time, galleries become this island among this ecosystem that’s been existing for some long and they shut themselves out to the direct local community that they have there. At 3 o’ clock everyday when school finishes, this street is just full of kids going home, it’s absolutely packed and we leave the door open; it’s slowly changing because they get to know me and my space, but initially it wasn’t somewhere they felt they were allowed to be in. If you’re aware of it, and actively try to do events for the community, then you can’t stop it from happening but you can allow it to have some kind of positive impact.

There’s a lot of talk of gatekeeping in the art industry, what are ways of combating that?

I come from a music background before I switched to study art, so I’ve always been very much a person that believes in integration of creative fields, and beyond creative fields as well. We put on club nights — we have a gig in the space tomorrow — it’s about making connections to spaces where people do feel comfortable, and then having them connect to the gallery in a way that does not only support other practitioners, beyond just artists, but it’s also an acknowledgment that a DJ is of the same creative intellectual level as a painter. It’s funny because people say ‘you don’t want to do too many club nights because then people won’t respect the gallery program.’ But that is the gallery program. I think it takes people a while because with nightlife, and this show does touch on that, it’s criminalised to a point and people just dismiss these places as sites of revelry and illegal things, people having a good time. I think there’s something very political about having a good time, especially in this day and age.

How often are the shows?

It’s slightly rigid because I share the space with another gallery, Danuser and Ramirez, where we basically have two completely different programs. So the shows are a month-long and then we switch. What people don’t realise, especially with young, new spaces, we do often all have jobs as well. Especially when you’re starting out, it’s not really financially viable to chuck your whole life into a space. If you walk down Deptford High Street you’ll see that most of the shops there have two or three businesses in turn. There will be a guy selling phone cases and then a guy at the back doing money transfers and then fruit and veg at the front. I think we might start to see it a bit more as a format for galleries because London rent is not getting any cheaper.

Freddie Powell, Ginny on Frederick

Is there any meaning behind the name: Ginny on Frederick?

Ginny is my mother’s name. I stole her credit card when I was 21 to do a show in a hotel room with Alexandra Metcalf, an artist based in New York, and you needed a credit card to put on the hotel room. Frederick is my name but it also relates to when I first false-started the gallery in Haggerston and it was on Frederick Terrace.

You started your career at the White Cube, why did you see potential for your own gallery in a sandwich shop?

I was the front desk girl and then I took over the bookshop there. At the same time, I was doing some curatorial projects elsewhere and the pandemic shifted things. I opened this space in an archway in Hackney in January 2020. We did one show and it quickly closed down. In summer 2021, when Covid dipped a bit, I found this space walking around Smithfield Market. It was really affordable, so it made sense. I love the tiles, they draw a lot of people in as they’re quite nuts.

What makes your programming unique?

The majority of the people I work with are around my own age so they are really my peers. I really like working with artists on their first or second show, and there are themes that go through the programme of sexuality, power and gender, but I also sometimes work with an artist because I think they’re interesting and I just want to go to their studio and see someone who is really obsessed with what they are doing. I think obsessive practise is really interesting. How then, can I, as a gallery, facilitate that? Jack O’ Brien, who was the first show at Ginny on Frederick, he was sharing a space with Eva Gold, and then that led to her show. Jack is friends with Sam Cottington, who was in a group show here; Alex Margo Arden and Rachael Crowther both go to the RA. I’ve become this space where all these pre-existing relationships are reconnecting again.

What are the benefits and challenges of such a tiny gallery?

I purposefully kept my overheads really low and that was some good advice I got at the beginning. My collector base was really brave because they were buying from this cowboy kid in a sandwich shop but the legitimacy of the gallery allowed me to reach a wider net. The ‘by appointment’ thing was because the space can only exist in that way because there’s no toilet or running water. It’s really a traditional art gallery, just in a mad space.

Zina Vieille and Nnamdi Obiekwe, V.O Curations

You occupy buildings that sit empty while property developers decide what to do with them — what made you think these would make interesting creative spaces?

As developers are key actors in the evolving landscape of our city, we have always advocated for the responsibility they have in supporting the creation of cultural value where possible. We’ve always been excited to present visual art within incongruous spaces, and embrace the unconventional framework that an office block provides. We launched VO Mayfair in January 2021, and have secured it through to 2026. We will be expanding our footprint to provide further studio space within the facility from later this summer.

How does the space impact what art you choose to show?

We’ve found that occupying office buildings and the unconventional nature of these spaces was much more unique, departing from the traditional ‘white cube’ or common expectations. We believe that showcasing great bodies of work doesn’t require a particular setting and that this was even secondary – our focus remains on curating exceptional and engaged programmes.

What were your reasons for creating a new art space in London?

The launch of V.O was driven by our desire to bring emerging and underrepresented artists to central London, providing them with easier access to opportunities, resources, networks, institutions and galleries. Highlights have included Rhea Dillon, Sandra Poulson, Dala Nasser, R.I.P. Germain, Ebun Sodipo, Mohammed Sami, who have touched on issues relating to diasporic identity, and disseminating post-colonial frameworks and ideologies.

We aimed for a dynamic model: studio provision for hundreds of London-based artists, commissioning emerging artists to present their first major exhibitions in the UK, and development of a highly-respected residencies programme to offer opportunities for artists to research and develop new work. For over 700 makers we have supported since our inception in 2019, we have aimed to provide not only physical space but also a community of relatable peers with access to networks and professional support, all whilst alleviating the pressures that arise from traditional gallery settings.

Rose Easton, Rose Easton

When did you open your gallery, and why?

We (myself and Tom Shickle) opened as a project space in October 2021. At the time I was working for another gallery called Soft Opening, just down the road. We got the space in September and, within a month, managed to pull together a two person show with Jack Jubb and Lotte Andersen. My husband built out the space and the whole thing was pretty DIY: we called the gallery Moarain House, which was the name of the building, and chose a font from Word. I remember being in the gallery at 3am the night before wearing goggles, spray-painting the ceiling. We didn’t set up as a company or open a bank account; we thought it was going to be a side hustle on the weekends, but the first Saturday, some collectors came in and bought a work and we realised it could be a thing. We fell in love with having a space, programming shows and working with artists.

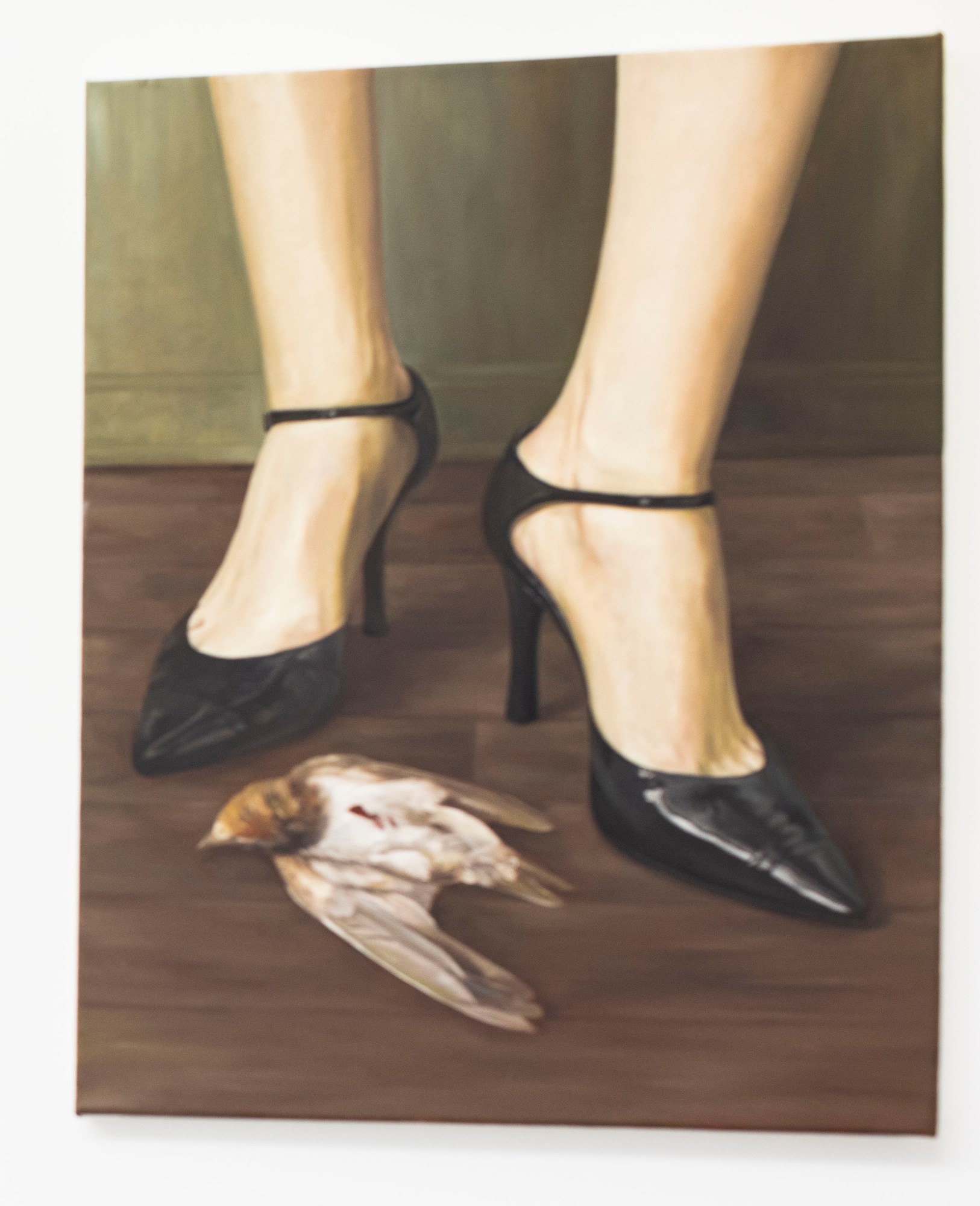

Tell me what kind of art you gravitate towards.

I’m definitely more drawn to work that has a sculptural underpinning – everything we show has that language embedded in it, but in very broad terms; I think of both video and audio sculpturally. It’s also about an understanding of, and attention to, space; artists that have an interest in engaging with the gallery environment as a whole and making use of the quirks of the building. For Solomon Garçon’s show, we turned the gallery into a warped version of his council flat. We boarded up the windows and plastered over them so it became a sealed room, then we built in columns, pipes, skirting boards and fake plug sockets, and spray painted the entire gallery from floor to ceiling in one colour, light fixtures and all, with a sound work that filled and altered the architecture of the space. The artists that I programmed at the beginning are some of the artists that I’m still working with now: Amanda Moström was in the third show we ever did and this is number 11.

Tell me about the area you’re in.

There are lots of galleries around Bethnal Green. I’m on a street with four other galleries. They are all much more established. I’m the baby and they have really welcomed me in. Maureen Paley is the original and has been here for many years, Herald Street is in this same building, while Mother’s Tankstation and Project Native Informant are just a few doors down.

Why is this space special?

This used to be Wolfgang Tillmans’ studio and then a gallery called Campoli Presti, so it has a rich history and good juju. It’s one of the last older buildings and that has its drawbacks: it’s terrible in extreme weather and nothing works that well, but it is also gorgeous.

Oyinkansola Dada, Dada Gallery

When and why did you set up Dada Gallery?

It started as a blog back in 2017, where I would write about literature, art and politics. Then it became Dada Gallery in 2021 when I started doing exhibitions. I briefly worked for an art fair and developed relationships with different artists. I started selling affordable art prints on the website and that’s where I became properly invested in an artist’s career and having the full scope of representing them. I wanted to have this space and a platform that highlighted the work of Black artists from Africa and across the diaspora: a gallery that reflected important issues for young Africans and young Black people, surrounding identity, queerness, migration.

There really aren’t that many Black-owned galleries in London, so that’s quite exciting to be pioneering in that space. Why do you think that is? And why is it so important for those spaces to exist?

Honestly, I think there’s a range of issues. There needs to be more education and ownership in terms of Black people feeling part of the art world. In Nigeria, most of the galleries are Black owned with the exception of a few. For me, coming from Nigeria and seeing many examples of galleries owned by Black Nigerians, it wasn’t a wild concept to do that. But I was also very aware, especially when I moved here, that a lot of the galleries that were showing Black art were white, and I think that a lot of it is an issue of access, especially in the West. I don’t think it’s easy for people from different backgrounds to get into the art world because there are just such high barriers to entry. Most people that go into the art world or start galleries are from privileged backgrounds. That’s why I decided to start small without a physical space, because physical space is really the biggest barrier.

You don’t rent a gallery space but do put on exhibitions, how does it work?

We’re members of Cromwell Place, which is in South Kensington. Galleries can become members of the space, and use it whenever they want. What happens is we only pay for what we use, and I think that that’s very helpful, because the rent prices in London are extremely high. It means that I’m able to do around three or four exhibitions a year and also do art fairs in London, Nigeria, Paris; we just did one in New York. But the next phase is getting a permanent space in Lagos, as well.

Jacob Barnes and Morgane Wagner, Grove

Why did you launch the gallery when you did?

Jacob: The reason we launched in January 2021 was, in part, because we felt as if we were part of this brave new world, and this moment where the lid had been blown off what was possible. We realised it was going to be now or never to help shape what this new world is going to be.

What did you want that to look like?

Jacob: We wanted to run a gallery that was reflective of what it meant to be a professional, young, creative, and help service those needs instead of being, I think, exploited is a really strong word, but being extractive – trying to just take from others and build ourselves up, while kind of leaving others to not really make those same jumps. We wanted to set up an organisation that felt like if we grew, and our friends and peers grew, then we would all grow together.

Morgane: I think with that, talking about a sense of community, is also an openness to talk, to share, to discuss. The art world can be quite secretive. We want to make sure that everybody feels as welcome as possible into our space.

What makes your business model different to other galleries?

Jacob: First, we guarantee an income for the artists we represent – they’re all on full-time wages. When we take representation, we figure out the number of works that we’re expecting to consign over that year, find a median value and take half of those works, and then come up with that number that says we’ll guarantee this, so either we sell your works and you make X amount, and if we don’t, then you still get that amount, and we pay out every quarter.

Morgane: Jacob does a lot of the artist liaison, making sure the artists feel looked after, well-heard, while also giving advice. I think it’s hard sometimes, especially as an artist when you leave art school, to find a community other than your friends when you’re looking at the business side of things, who you can listen to.

Jacob: The way we work with artists is very much oriented towards a longer term. You only stick around for a long time if you stick to your values. There’s going to be periods where there’s not a ton of money, there’s going to be periods where the popularity of shows wanes – that’s going to happen over the course of your career. But you stick around because the people in your community will stick by you. And they’ll help you out when you need them.

How would you like the art world to change?

Jacob: I don’t just want to say just that the art world needs to be more representative, museum collections need greater percentages of LGBTQIA and BAME, and all these communities need to be better represented in the art world. But I feel like if I said that I’d been neglecting the very foundational elements of like, it needs to get over itself. It’s just not that cool.

Morgane: Let’s have fun.

Jacob: You can run equitable, sustainable businesses in the art world. It’s tough. And it’s not going to be easy on a day to day basis, but it’s possible.

Credits

Photography Scarlett Casciello