Last week Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography opened, a new show at the Barbican which explores masculinity in its many guises. The exhibition is great; an “all killer no filler” collection of photographs that is equal parts playful, poignant, tragic and erotic. It’s diverse in every way you could hope for, featuring a mixture of artists from around the world, sections which focus on race, transmasculine subjects and bodies affected by disability, age and addiction.

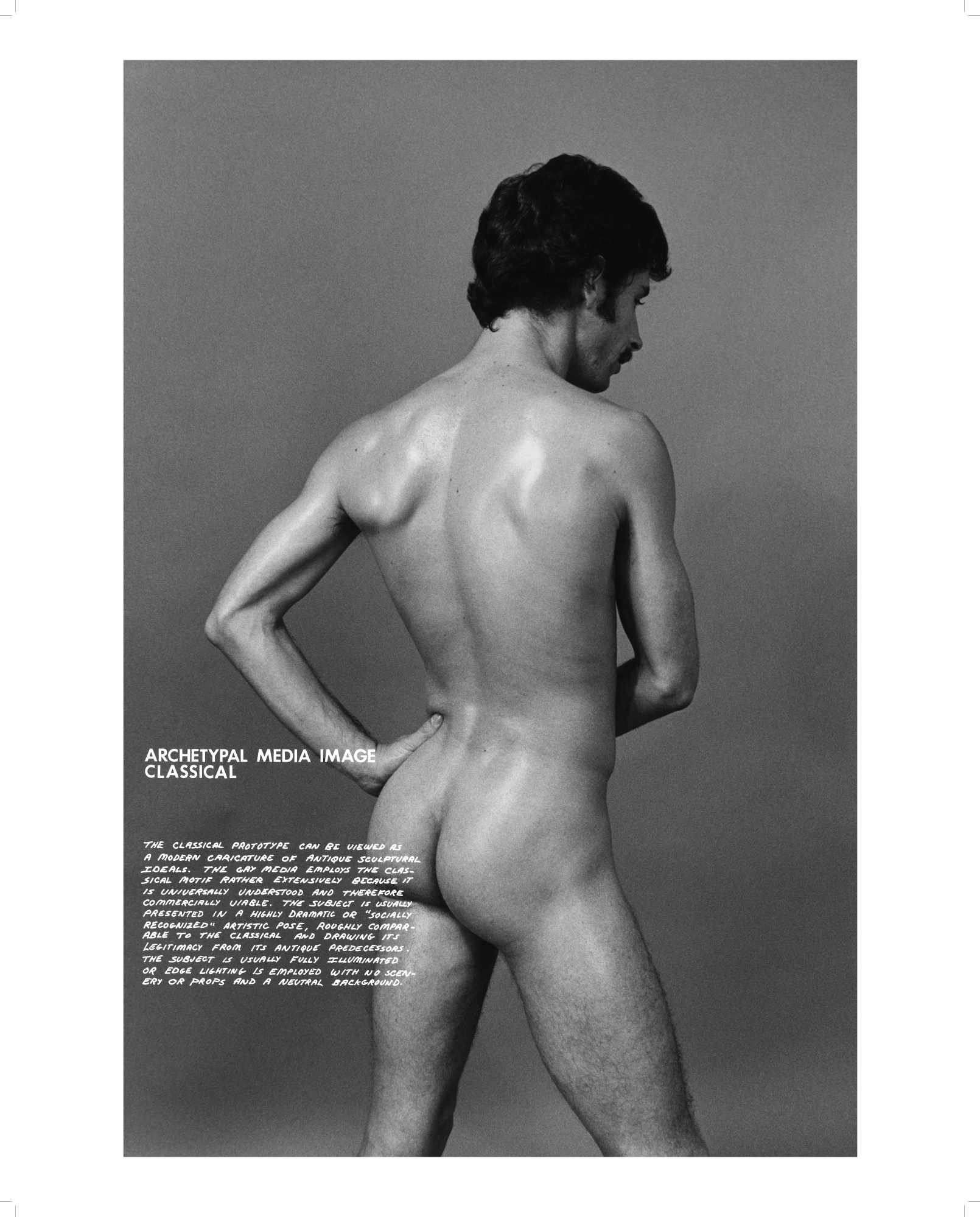

It would be inaccurate to suggest that the exhibition is merely a parade of beefcakes — there’s a lot more to it than that — but muscularity does play an important role in how masculinity is constructed, which raises some interesting questions about the extent to which the two concepts are intrinsically linked. In an age of increasing male body anxiety, what does it mean that the ideal masculine body is still so flawlessly ripped, so perfectly sculpted, so difficult to obtain?

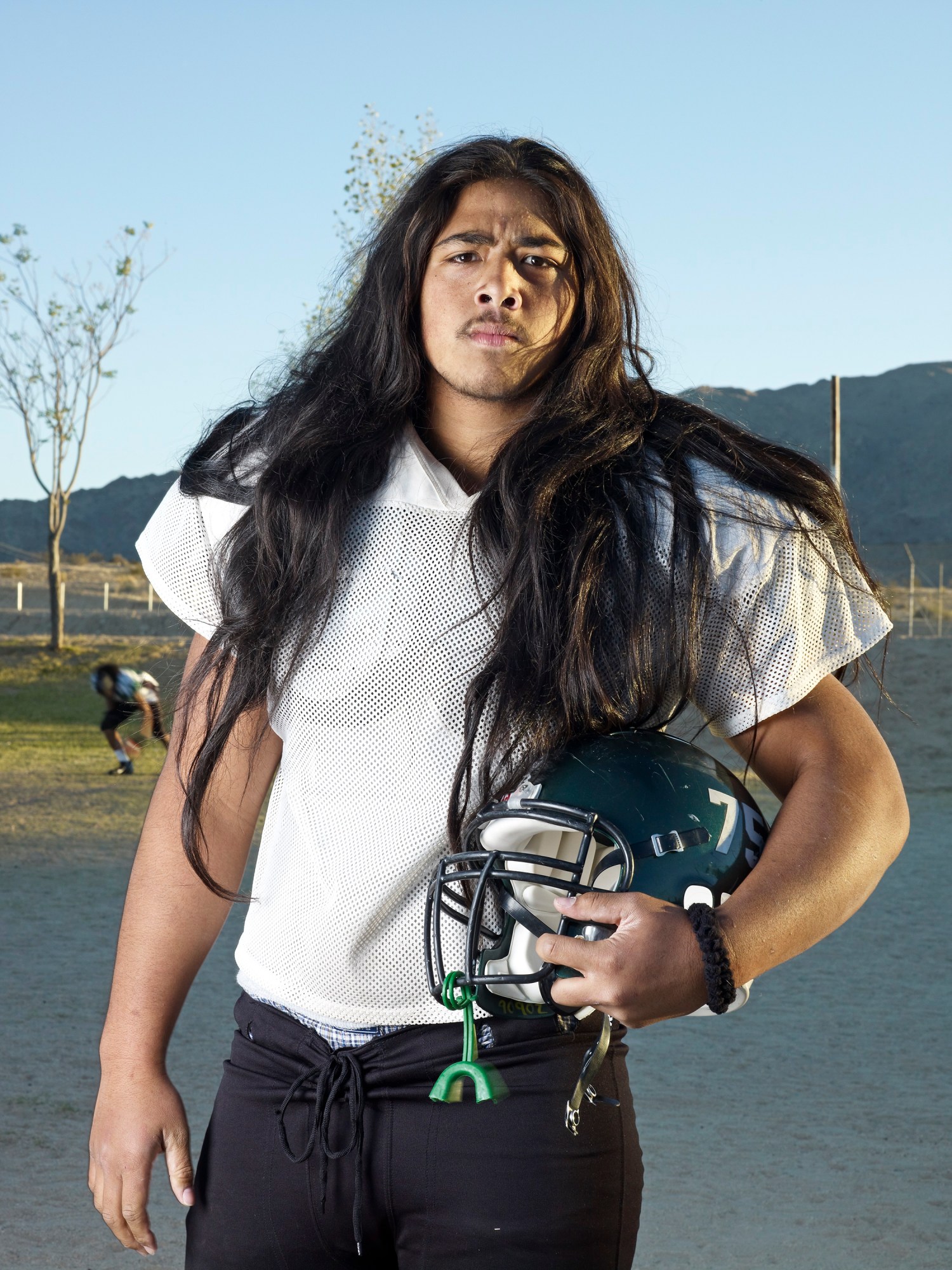

“We wanted to examine and scrutinise the performance of manhood through the body,” says Alona Pardo, the exhibition’s curator. “It’s not the only thing but the virile male body is critical.” The muscular male body is featured in a number of works. Sam Contis’ Deep Springs series depicts rugged cowboys and labourers in barren landscapes which feel like a Lana del Rey song brought to life. Catherine Opie’s High School Football series meanwhile, concerns another American archetype — the jock. In both works, typical masculine strength becomes a form of timeless American tradition.

A section of the exhibition dedicated to queer masculinity places Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of Arnold Schwarzenegger and female body-building champion Lisa Lyon side by side. By showcasing a strong woman, who is depicted as more intimidatingly powerful than the image of Schwarzenegger beside her, this pairing succeeds in divorcing masculinity from gender and sex. But it still shows how muscularity is often still a big part of female or trans masculinity, a relationship which is also suggested by the work of transmasculine performance artist and bodybuilder Cassils. Time Lapse, their series of self-portraits, shows their body in a state of flux, as something which changes but consistently embodies certain normative standards of muscularity.

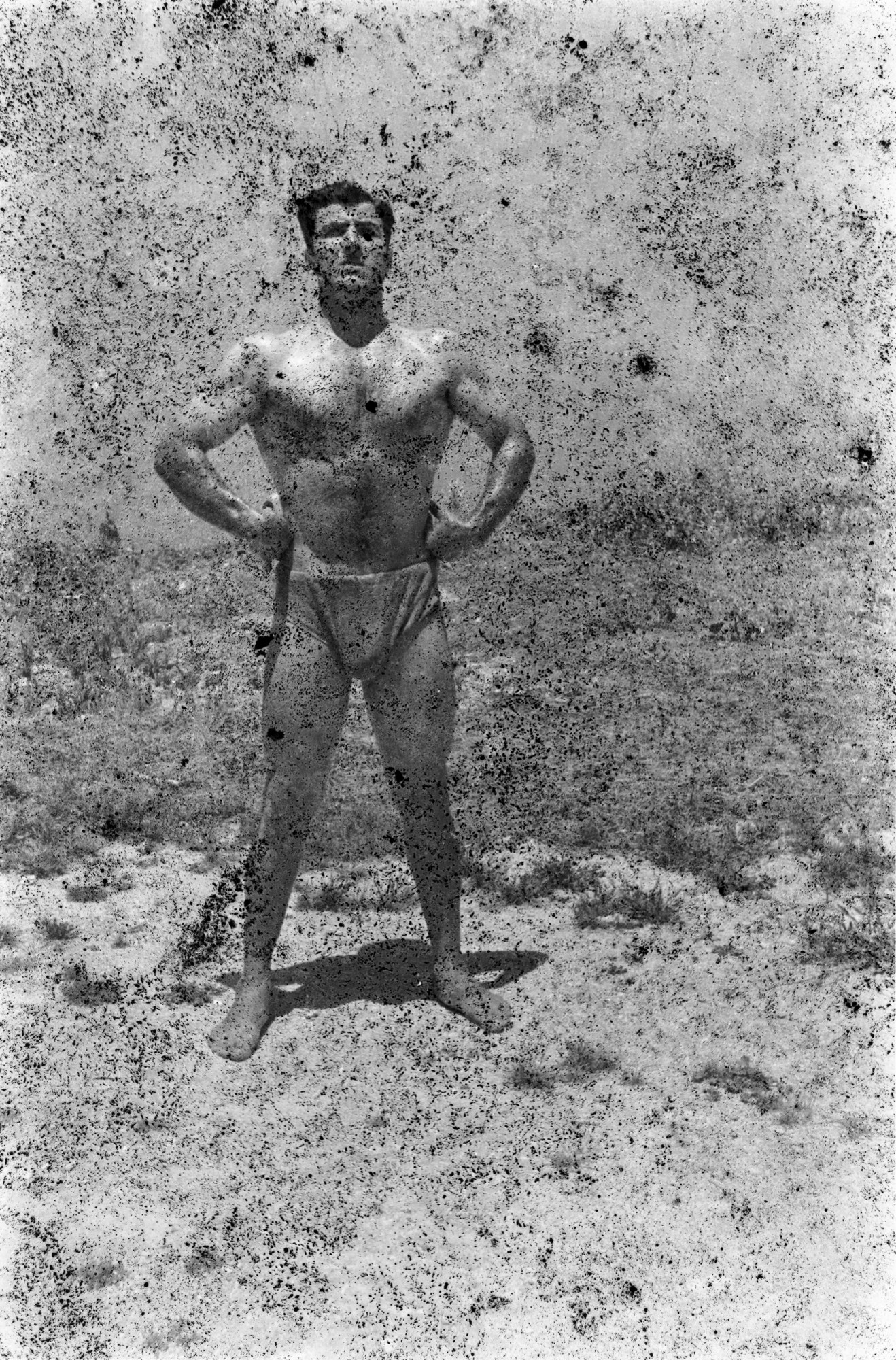

Bodybuilders recur as subjects throughout the exhibition, such as in Akram Zaatari’s series of photographs of Lebanese bodybuilders. These were produced from damaged negatives which were found in an archive and as such are extremely disfigured and covered in blotches — something that gives a deeper sadness to the melancholy inherent in so many old photographs. “The surface of the photos have a fragility which seems to enhance the fragility of the bodybuilder and the precarity of the body,” says Alona.

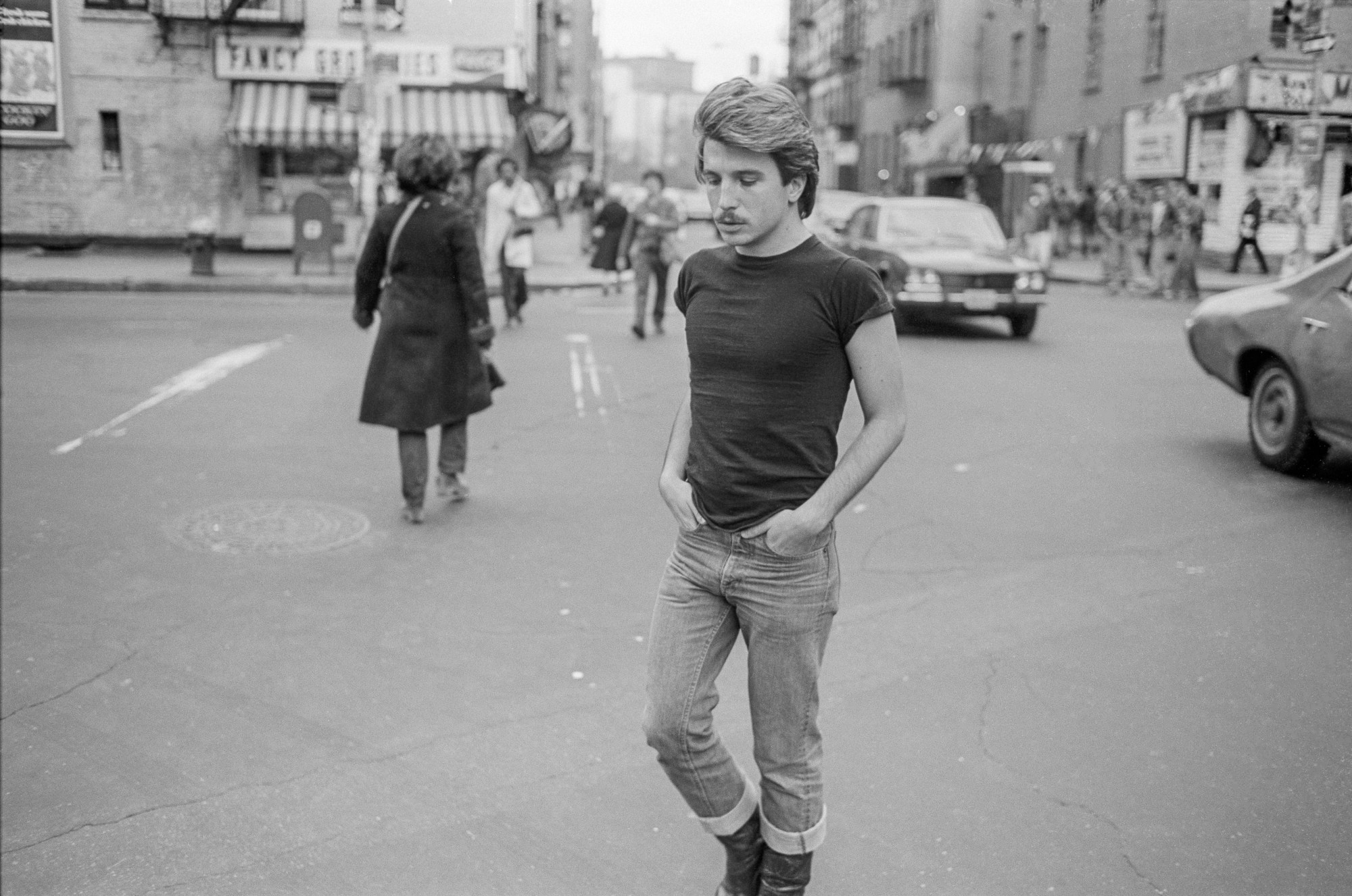

Elsewhere, Sunil Gupta’s street photography capturing Christopher Street in the 1970s — which was then the epicentre of gay life in New York — observes the “clone” look, a hyper-masculine aesthetic comprised of muscles, boots, moustaches, blue jeans and leather jackets. Rotimi Fani-Kayode, meanwhile, explores black manhood through stark black-and-white portraits of physically powerful men. We see that, across different contexts, muscularity frequently appears in depictions of masculinity.

But that’s not to say that the exhibition doesn’t problematise this; not least via the enormous four panels which greet you as you enter. “We start with the male body in John Coplans’ work, which shows the complete opposite to the muscular body. We wanted to start off by completely overturning that sense of muscular figure, and show a representation of something soft and imperfect, saggy and old,” says Alona.

One particular highlight is Richard Billingham’s hugely affecting Ray’s a Laugh, an autobiographical photo series concerning Billingham’s alcoholic father. In these images, one of which features the titular Ray in a state of undress, the absence of muscles conveys a sense of vulnerability, frailty and the ravages of addiction (perhaps unfairly, given most topless men in their sixties would probably look similar). In a completely different way, George Dureau’s photographs of amputees and people with disabilities also challenge conventional visions of masculine beauty; unashamedly erotic and viewed through a gaze with is neither pitying or prurient.

If there’s one area of masculinity where beauty is perhaps absent, or at least completely irrelevant, it’s political power — another key theme of the exhibition. Masculinity is bound up in governmental and economic power as much as athleticism, which is evident in the portion of the show titled Male Order. The men depicted here are not muscular, lithe, or conventionally attractive, because they don’t need to be. Being rich means that you can exercise power without being virile, beautiful or physically strong, as every wealthy middle-aged man dating a beautiful 21-year-old can tell you. Richard Avedon’s The Family (a series of photographs of key American politicians, military men and captains of industry in the 1970s) is cheekily situated next to Piotr Uklański’s The Nazis — a series of tightly cropped portraits of actors playing German villains in Hollywood films. Power, in both sets of images, is not derived from the body, but from institutional power, wealth and authority.

All in all, there’s certainly enough in the exhibition to muddy the connection between muscularity and masculinity. But how has this relationship played out throughout history? Has the idealised male body always been muscular?

Yes and no. In antiquity and again during the Renaissance, the standards for what constituted a conventionally attractive man are more or less the same as they are now. But there’s a flip side to this: while muscles have always suggested a certain virility, they have also been associated with physical labour and therefore, much like tanned skin, viewed by the upper classes as vulgar. Many artistic depictions of upper-class men, particularly between the 17th and 19th centuries, portrayed them as slender and pasty, both of which signified power. Looking like this indicated that you were never forced into doing anything as déclassé as tilling a field or lifting anything heavier than a silk-spotted handkerchief. Skinniness has been associated with masculinity and male beauty at several points in more recent history, too: think glam rock in the 1970s and 1980s, heroin chic in the 1990s and indie, Hedi Slimane-esque skinny jeans in the 2000s.

Perhaps a valid question raised by the exhibition is whether having these idealised images of perfect bodies can be harmful. If the increasing prevalence of muscular bodies in our lives via social media has contributed to the rise of disordered eating and exercise addiction among men, can we separate idealised portrayals from normative standards? Being properly ripped requires a level of monk-like dedication so one could wonder whether it’s a particularly healthy thing to aspire towards. But, as much of the work in the exhibition suggests, these implausible bodies can still be beautiful to behold.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is on show at London’s Barbican until 17 May 2020.