“I like the idea of subverting something that’s regarded as submissive and docile and saying something quite strong with it,” says Bristol-based embroidery artist Sophie King. “It appeals to my sense of humour to subvert assumptions.”

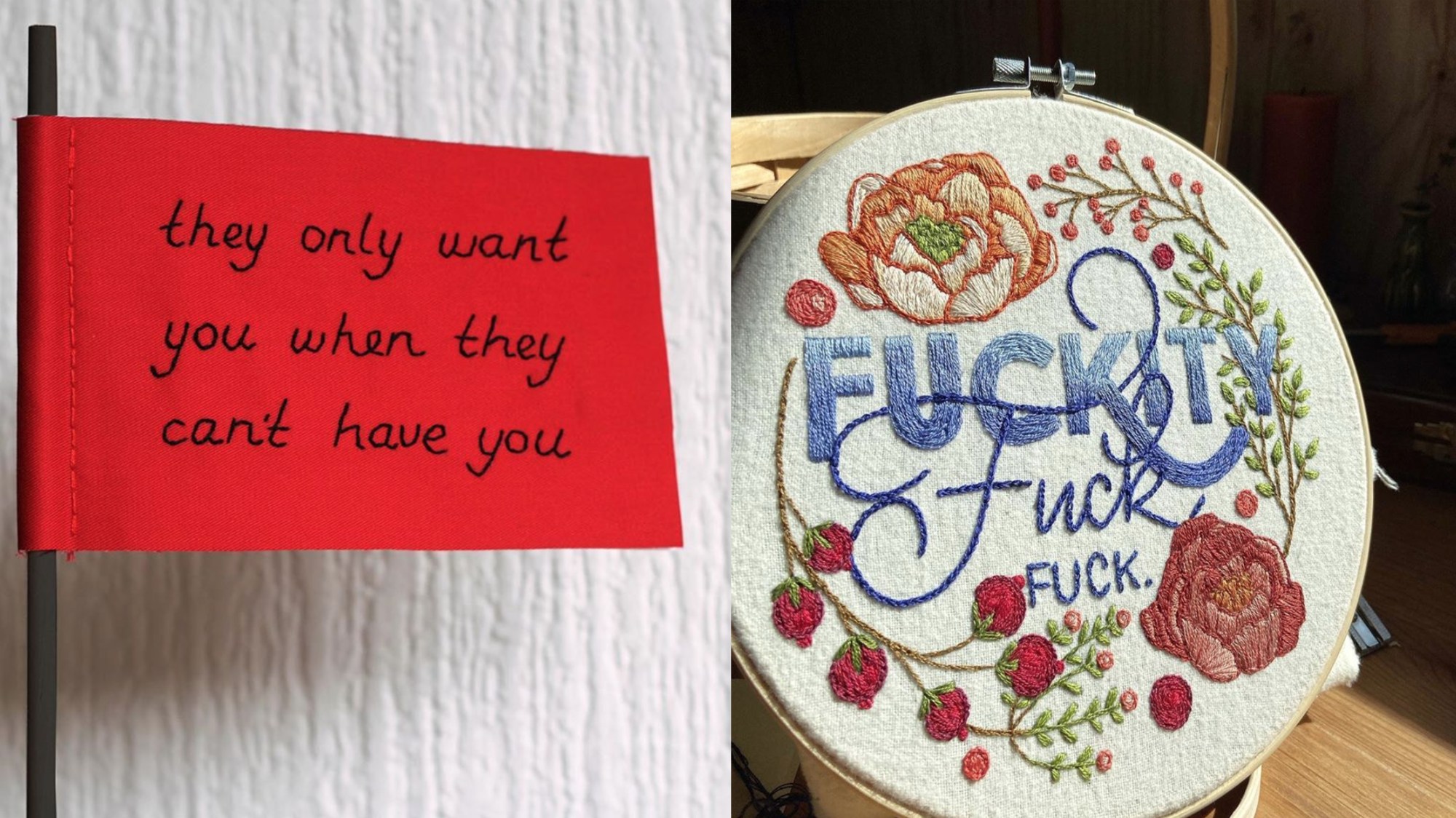

The 29-year-old started sharing her embroidery on Instagram in 2013 and since then she has been using the medium to spotlight feminist issues. The phrases she stitches have since gone viral and been shared countless times. She focuses on deconstructing gender roles and holding men accountable in heterosexual relationships. For her Red Flag series, Sophie stitches relationship dealbreakers onto literal red flags.

To some, embroidery might seem like a ritual from the past — Victorian women stitching together by the fireplace. However, in the past few years, social media has become a vehicle for a craftwork revolution. Instagram feeds like Sophie’s are shareable and eye-catching, but more than that, they provide opportunities for contemporary embroiderers to get their work out there. And while traditionally embroidery may have been associated with floral, pastoral or Biblical art, this new wave of young, primarily female artists are reclaiming the craft as a platform for social change. Their work, rather than focusing on Bible verses or beautiful flowers, is inspired by issues as diverse as gun violence and gaslighting.

“Folks associate embroidery in particular with ‘Home Sweet Home’ and cats and bunnies and Bible quotes so when strong messages come through that medium, it stops them in their tracks,” explains Shannon Downey, the artist/activist behind @badasscrossstitch. In 2017 her “Boys Will Be Boys” piece became a social media rallying cry in response to Harvey Weinstein and #MeToo, and was seen around the world after being shared by celebrities including Emily Ratajkowski, Willow Smith and Zoë Kravitz.

Activism and embroidery have always gone hand in hand for Shannon, though initially it might seem like a striking juxtaposition. “My activism is my life so it just made sense that I would be stitching around these topics,” the Chicago native explains. Embroidery not only gives Shannon a tool with which to start conversations online. She finds that the act of embroidering itself allows time for reflection. “I use it as a way to give myself time to think about different issues and topics,” she says. “It is a bit of a meditation for me. Anything I’m stitching is something that I want to spend time thinking about, whether it’s feminism or politics or gun violence. It creates space for me to be quiet.”

In our anxious times, many of us are on the lookout for new healthy coping mechanisms and ways to support our mental health. When artist Sarah Beth Timmons, who’s based in Salt Lake City, Utah, was suffering from postpartum depression, embroidery was invaluable. “It was good for me to have something to do with my hands,” she says. “I could watch a TV show and completely forget about my worries. I think it’s really beneficial to get your fingers moving while your brain does something else.”

Sarah started by stitching swear words, which feature on her most popular pieces, after getting into trouble for swearing at work. “I was in meeting and I said ‘Fuck’ because I was really frustrated. I didn’t direct it at anybody, but they almost fired me for it,” Sarah explains. “I went home that day and started to embroider ‘Fuck.’ I thought it was so funny because my grandmother taught me how to do this and my grandmother’s house has the sweetest embroideries and now, I’m making these. The whole thing makes me laugh. People really respond to swear words in embroidery. It’s a funny juxtaposition that people love.”

But more than the messages these artists choose to champion, it is the art form itself that is perhaps most political and lends itself most to activism. Anyone, after all, can take up embroidery. The materials are affordable, and the ability to be self-taught, for instance via YouTube tutorials, makes it a remarkably accessible technique. With its close ties to sustainability, craftwork is increasingly popular, too, as a way of pushing back against mass-market consumerism, particularly among millennials and Gen Z.

Shannon’s practice, in particular, is dedicated to passing on the collaborative, female-led aspect of teaching embroidery to a new generation. The artist wants to introduce as many people as possible to the craft, hosting regular “stitch-ups” in and around Chicago. She will soon be setting off on tour, driving a van across the US, teaching classes in every city she stops in, a project that she hopes will continue into 2021. “It’s such an easy medium to learn so I can teach somebody in 10 minutes how to do it,” Shannon says. “It’s a low entry point in terms of cost and materials. You don’t have to commit to buying a big instrument to learn this hobby. It’s ten bucks and you’re good to go.”

Historically, it’s embroidery’s accessibility which has been used as an excuse to not take the art form seriously. With women historically being shut out of art schools and academies, embroidery was one of the only crafts they could easily engage in from the home. It’s been in Sarah’s family for generations, but her mum still couldn’t believe that people were willing to give her money for the embroidery art she was creating. “It was women’s work,” Sarah says. “Embroidery was really the only art form we ever had. It’s taken a big leap in the past 10 years from being strictly what you do with women in a circle, dating back to King Arthur probably. Now, we’re doing it still, but it’s kind of a higher art form.”

However, there’s still a struggle to get people to recognise embroidery as a medium that’s as worthy of appreciation as more mainstream forms of artistic expression, like painting and drawing. “People say small things about embroidery that are patronising,” says Sophie King. “I’ve done traditional art and I can tell the difference in reception from people. I embroider because I love the medium but it’s hard trying to fight people’s assumptions at the same time.”

The perception of embroidery is “highly gendered,” adds Shannon. “It’s crafty women’s work. That’s the general perception, although I believe that it’s totally shifting.” This shift is definitely in part due to the subject matter embroidery artists are tackling today. “I want to take embroidery from being perceived as a sweet lady grandma craft to people thinking ‘Holy shit, they’re taking over the world.’”