On hearing the word ‘bootleg’, thoughts typically turn to fashion. Of course, the industry’s relationship is both tumultuous and well-documented. There are numerous tales of precious house legal teams hounding after mom-and-pop operations in an attempt to protect their profits — and, more recently, tales of houses realising the profits to be turned by co-opting the slap-dash pastiche aesthetic that hawkers in both IRL and virtual marketplaces have pioneered.

But the history of bootleg is, of course, far more complex and dense than first meets the eye. More than a simple act of borrowing a brand’s logo to affect consumer desire, independent bootleggers have continuously proven the power of their craft to question just how that desire is generated, undermining capitalist understandings of power, privilege and exclusivity along the way.

“Bootleg disrupts hierarchy — you’re taking something exclusive that belongs to the few, and making it yours,” explains Anastasiia Fedorova, the London-based curator behind The Real Thing, an exhibition opening February 7 on the contemporary history of bootleg and brand obsession. “It’s an inherently political process,” she continues, “you can really change the meaning of something and adapt it to your community.”

The show comprises examples of such acts of reclamation, featuring the work of young artists like Roxman Gatt, who queers the autocratically masculine symbolism of car logos, or Akinola Davies Jr, who casts figures in fake Chanel hijabs in the same light you’d expect of a generously budgeted campaign.

But the exhibition is more than just the recent history of bootleg. It invites us to ponder the fluctuating relationship between brand and identity: how branding deeply influences our understanding of ourselves and the world around us; and how, when cleverly approached, branding’s capitalist logic can be subverted to powerful effect.

We spoke with the exhibition’s curator to hear more about how her interest in bootleg developed, her approach to selecting artists, and the importance of a pair of ‘Versace’ trousers.

What were your first encounters with bootleg?

My mum’s ‘Versace’ trousers! They had this gold embroidered lettering, which loosely looked like Versace. Looking at them later, though, it was clear that they didn’t even try that hard to make an exact copy. Growing in post-Soviet Russia, I remember seeing branding everywhere, but it wasn’t really used to imitate a luxury good; it was almost as a form of ornamentation. Brand identities would translate to totally unrelated things, like bed sheets or towels, or garments which have both Nike and Adidas on it, simply because the person making it perceived the logo to be beautiful.

I started revisiting those childhood memories when I was working in fashion. Seeing how ideas of authenticity, exclusivity and luxury are treated in the industry made me realise how weird those first interactions with fashion were, as well as how culturally constructed the distinction between real and fake is.

How did your initial fascination with bootleg become an interest in its symbolic value?

It was when I started looking more at original artistic work which addresses branding. I’ve always been fascinated by counterfeit culture — how branding travels and how its value transfers — and around 2015, artistic bootleg language started to pop up in fashion, like when Vetements did the DHL T-Shirt. But I was always more interested in how independent artists perceive bootleg: stuff that was tied to personal perspectives, or that had a strong social agenda. I came across Hypepeace quite early on, who did the Palestine pastiche of the Palace logo, as well as a few other designs to raise money for Syrian refugees, among other causes. They use the power branding has as something instantly recognisable, and inject it with new subversive meaning.

How did you go about selecting which artists to feature in the exhibition?

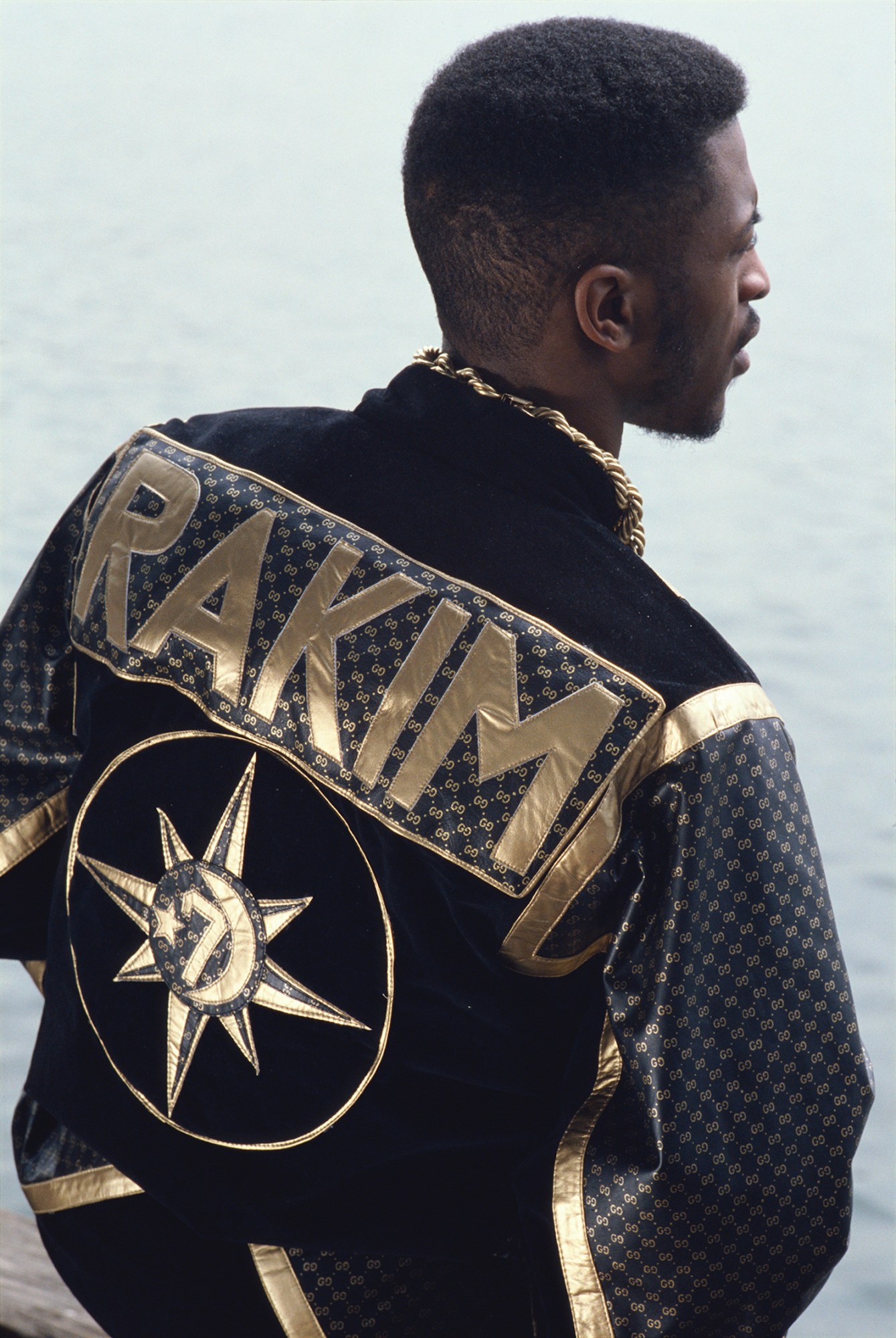

It was really important to feature the work of people who were part of the cultural history of the bootleg as an artistic practice, like Dapper Dan. I’ve been obsessed with his work for a while, and it’s recently had a big resurgence through his collaboration with Gucci. I’ve included this photography series by Drew Carolan, an album shoot for Eric B & Raki’s Follow The Leader, where they’re both wearing Dapper Dan’s custom Gucci outfits — I honestly think it’s one of the best hip-hop style moments out there.

Then there’s Dr Noki, aka JJ Hudson, whose work dates back to Shoreditch in the late 90s, and is connected to a cultural history of East London which has since completely disappeared — the original rave scene and the DIY fashion scene, for example. His work was also pioneering in terms of talking about sustainability and overconsumption, seeing branding as being a root cause of overconsumption and the ecological issues we now face.

Otherwise, I was thinking about why people engage in branding and what kind of issues they’re looking to address. There are two collectives doing work about immigration and refugee rights, and I was really interested in having a queer take on the subject, so I have the aforementioned Roxman Gatt, and two collectives, Nite Dykez and Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S), who are looking more at music and sound, and have a particular focus on issues faced by queer people of colour.

There’s also a video that Akinola Davies Jr did, which is partly inspired by Kingsland Shopping Centre [in Dalston, East London]. It employs the visual language of a glamorous fashion shoot, while portraying subjects which wouldn’t typically be used by fashion labels to portray their garments — women in fake Chanel hijabs.

Bootleg evidently has a lengthy history of relevance, but what can it teach us about the times we live in?

The fact that our reality is so branded — branding is literally everywhere! I think that for our generation, it’s even part of our memories, our dreams. As I mentioned earlier, it’s literally part of my personal childhood memories, for example. It’s good to be aware of that and not just take things as they are. We need to ask why our experiences are so branded, and who’s profiting from them. Bootleg is a means for us to ask those questions.

The Real Thing at Fashion Space Gallery from February 7 until May 2, 20 John Prince’s St, W1G 0BJ