Over the course of his seven-decade career, photographer Bruce Davidson has chronicled some of the most important stories of the 20th century — from the Civil Rights Movement to the rise of teen culture — documenting the lives of those on the fringes of society uniting to fight the systems of oppression designed to keep them down. On the cusp of his 90th birthday this September, the legendary Magnum Photos member talks us through The Way Back, a new exhibition and book showcasing unpublished work created between 1957–1977.

The Way Back sees Bruce weave together the intricate threads from his singular career to craft a majestic tapestry of rebels, outsiders and activists who redefined the image of mid-century America. “I’m just a humanist and photograph the human condition as I find it. It can be serious or it can be ironic or humorous,” he tells i-D. “If I’m looking for a story at all, it’s in my relationship to the subject – the story that tells me, rather than the one I tell.”

Photography has guided Bruce since he was a boy, coming of age in the Oak Park suburb of Chicago during the 1940s. By the end of the decade, he had a job at a local camera store and began his earliest experiments in colour. During the 1950s, Bruce studied with artist Josef Albers, graphic designer Herbert Matter and art director Alexey Brodovitch at Yale University, publishing his thesis, “Tension in the Dressing Room” – a look behind the scenes at Yale football games – in Life magazine.

It was a prescient start for Bruce, who refused to get derailed after being drafted into the Army. Stationed at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers in Europe outside Paris, Bruce honed his talents with assignments in the field before returning to New York in 1957. After working briefly as a freelance photographer, Bruce became a member of the renowned international photographic cooperative, Magnum Photos. The Way Back begins here.

Cast in the fading glow of nostalgia, 1950s America has become synonymous with the nation at its peak, a postwar oasis of privilege reflected in the shiny new television screens in every living room. But the image was largely an illusion and distraction from the matters at hand: homegrown fascism. With a backdrop of systemic government persecution against communism and LGBTQ people waged by Republican Senator Joseph P. McCarthy, the rising Civil Rights Movement garnered support across racial lines following the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till.

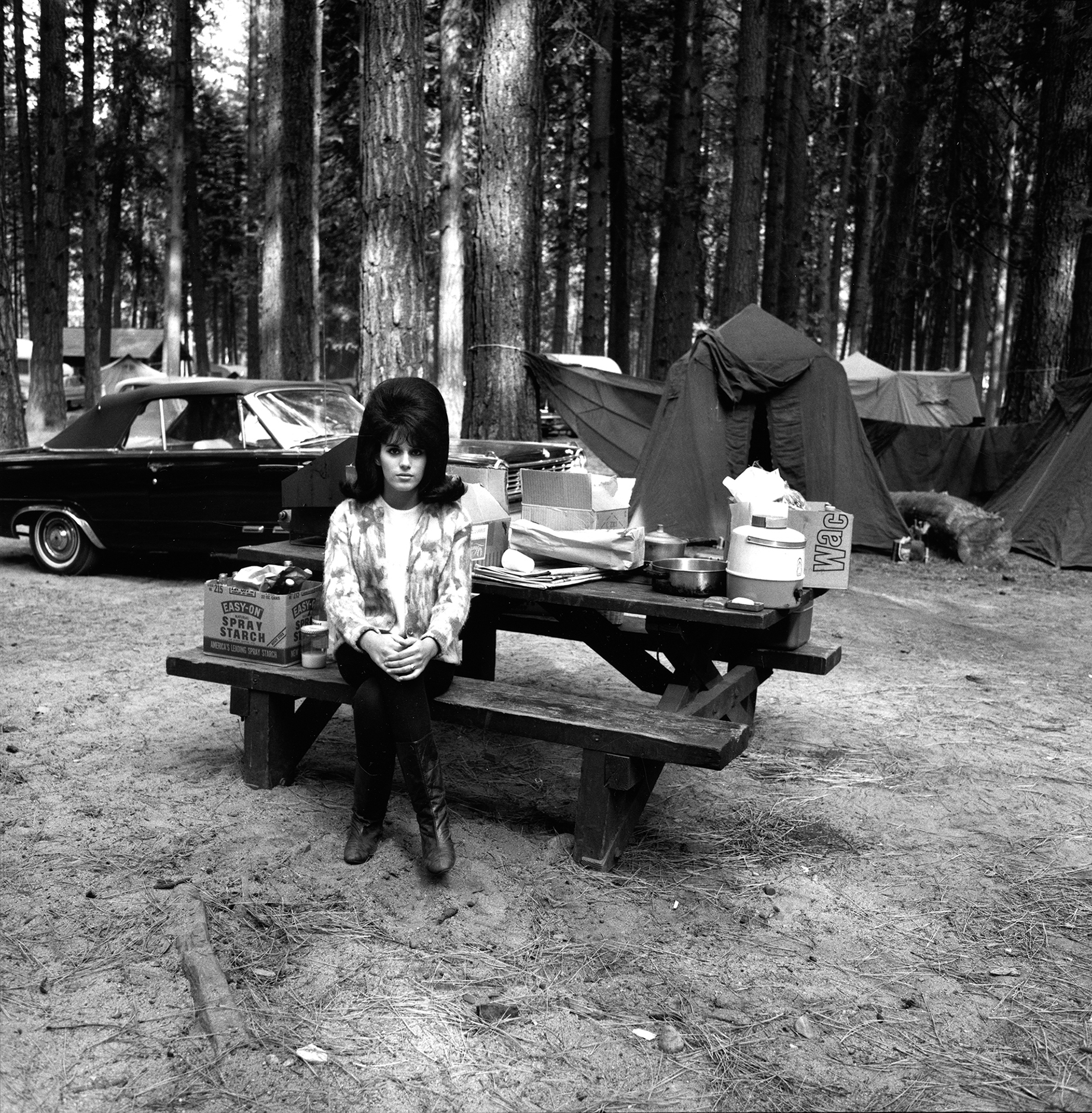

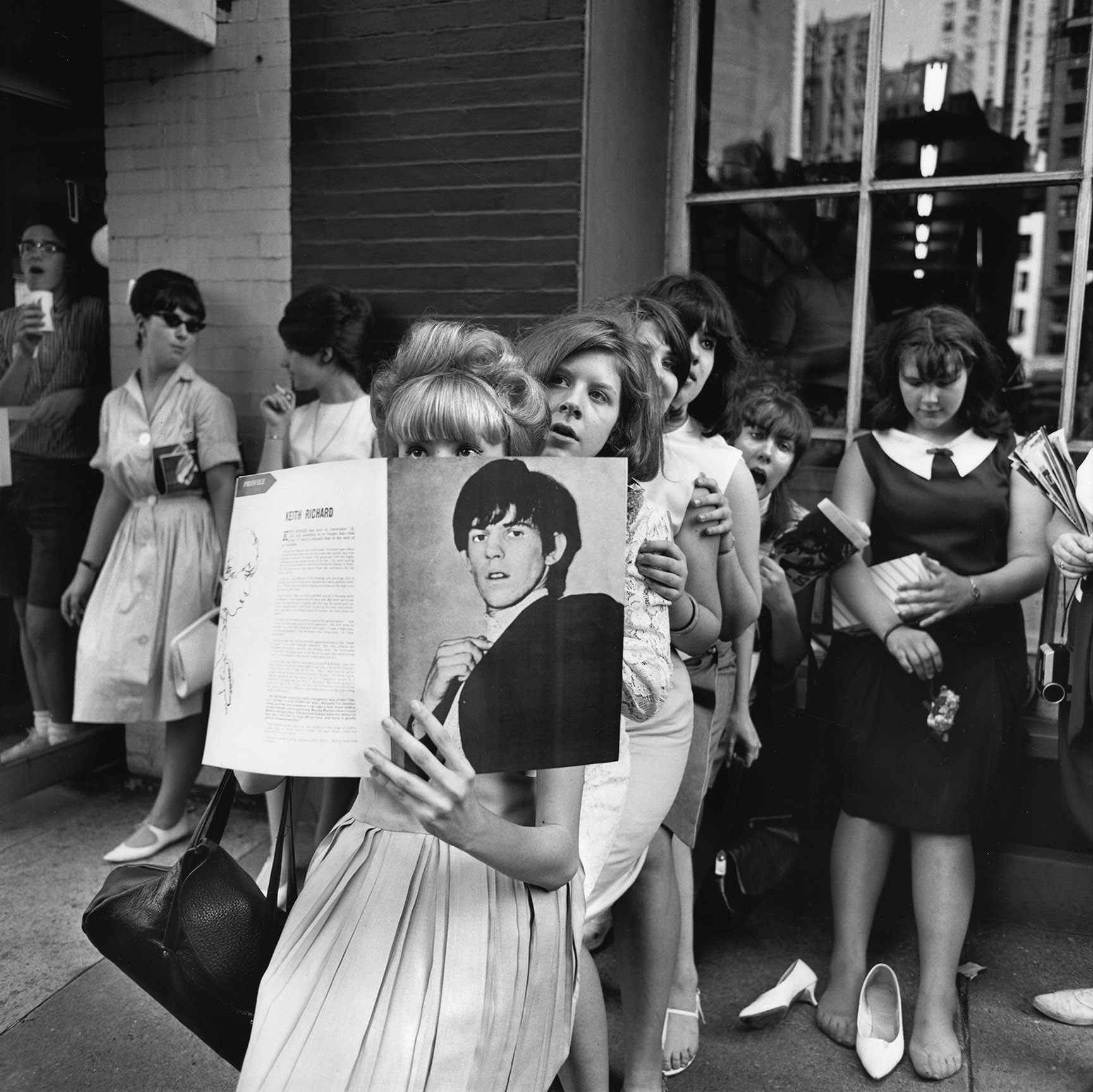

The veneer was starting to crack as the seeds of rebellion began to sprout. With the rise of teen culture, a new anti-hero took centre stage in Hollywood: the rebel without a cause. For a generation of working-class youth, reality was grim and they banded together in gangs to provide one another the feeling of family and a sense of belonging they didn’t have at home. Naturally, the media of the time had a field day, casting the youth movement as villains in a perilous crime wave destroying the fabric of the nation from the inside out. After reading a newspaper story about a local rumble on the streets, Bruce decided to see it for himself. He received an introduction to the Jokers, a group of high school teens and dropouts from Park Slope, back when the now-bougie Brooklyn neighbourhood was predominantly made up of working-class Irish-Americans.

Over the next 11 months, Bruce immersed himself in their lives to create the groundbreaking 1959 series Brooklyn Gang, which went on to inspire photographers including Larry Clark, Nan Goldin and Rineke Djkstra. Infusing the images with tenderness, empathy and romance, Bruce saw the vulnerability of these teens; restoring to them a humanity they were rarely granted. In these quiet moments of shared intimacy, he recognised the camera as the key that unlocked otherwise hermetic realms. “Brooklyn Gang is not really about gangs,” Bruce says. “It’s about emotionality and tension, abuse and abandonment. Those teenagers were poor and felt invisible. I spent almost a year with them and, in return, they gave me entrance into their dysfunctional world.”

With this insider access, Bruce garnered a level of mutual understanding and respect that formed the foundations of seeing and being seen. In the photographs selected for The Way Back, Bruce’s presence can be felt in these shared moments of trust. “My way of working is to enter an unknown world, explore it over a period of time and learn from it,” he says. “I work quietly and quickly, but also stand back to observe what’s in front of me. The main thing is to be open and honest and not intrude or make false judgments.” Esquire published the work to international acclaim.

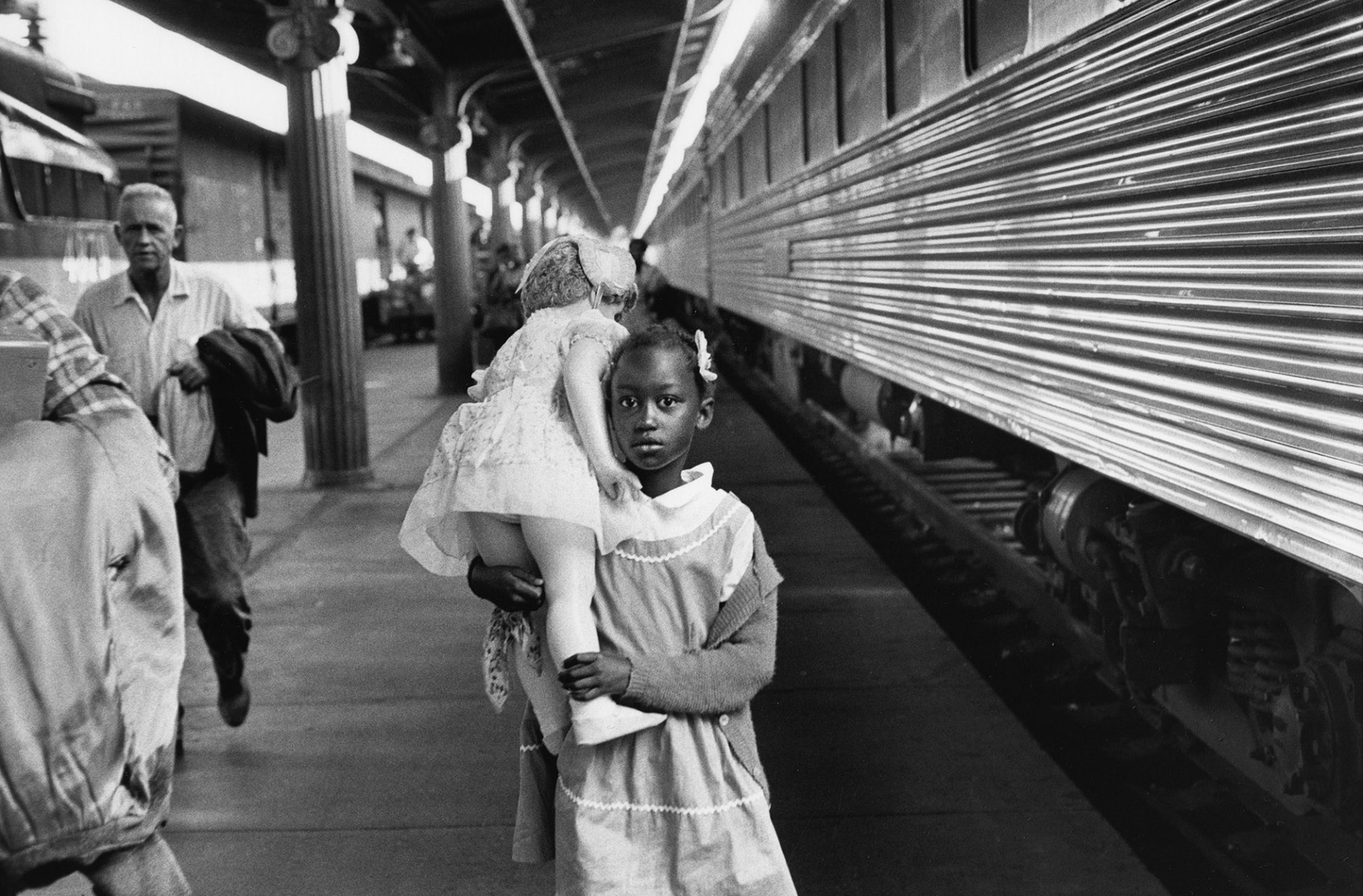

When Bruce won a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph the Civil Rights Movement, he embarked on a project that would later become the series, Time of Change. In 1961, he joined the Freedom Riders, a group of 13 Black and white men and women including a then 21-year-old Congressman John Lewis, who challenged segregation by riding public buses across the South. Local officials stood down and allowed the Ku Klux Klan to attack passengers with baseball bats and bicycle chains. John Lewis was beaten unconscious and left in a pool of his own blood, only to later be arrested and jailed for his non-violent efforts to end segregation.

“There’s an image in the new book of civil rights leaders John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and James Farmer holding a news conference to announce that the Freedom Rides would continue. This was in 1961, after the first bus had been attacked in Alabama and later burned on its way out of town,” says Bruce. “I boarded the second bus along with the National Guard as it carried the Freedom Riders to Jackson, Mississippi. I’d never been afraid of anything, but I knew it was dangerous for me to be on that bus. That experience sensitised me to something that needed to be recorded and something that I had to bear witness to.”

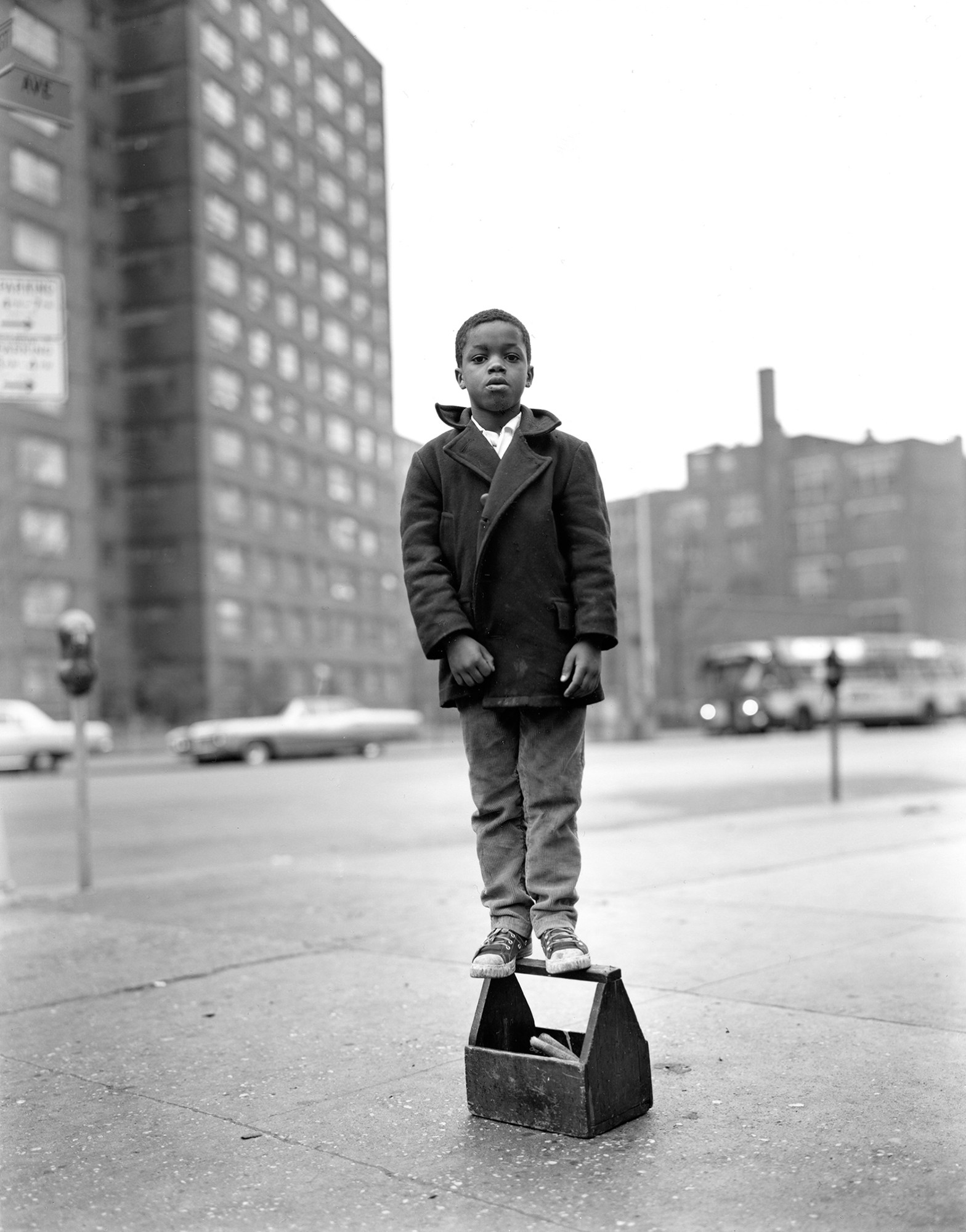

After completing Time of Change, Bruce turned his eye to his adopted hometown of New York City, a place where de facto segregation has openly flourished since the state abolished slavery on 4 July 1827. For the 1966-68 series East 100th Street, Bruce travelled to Harlem to chronicle the harrowing impact of environmental racism on the community. “The idea was to get these pictures in front of the mayor and city officials to improve the conditions of that community,” Bruce explains. “I felt that by documenting them, it was giving the community a human face and voice. I thought I could impart some positive knowledge through my work to make a change.”

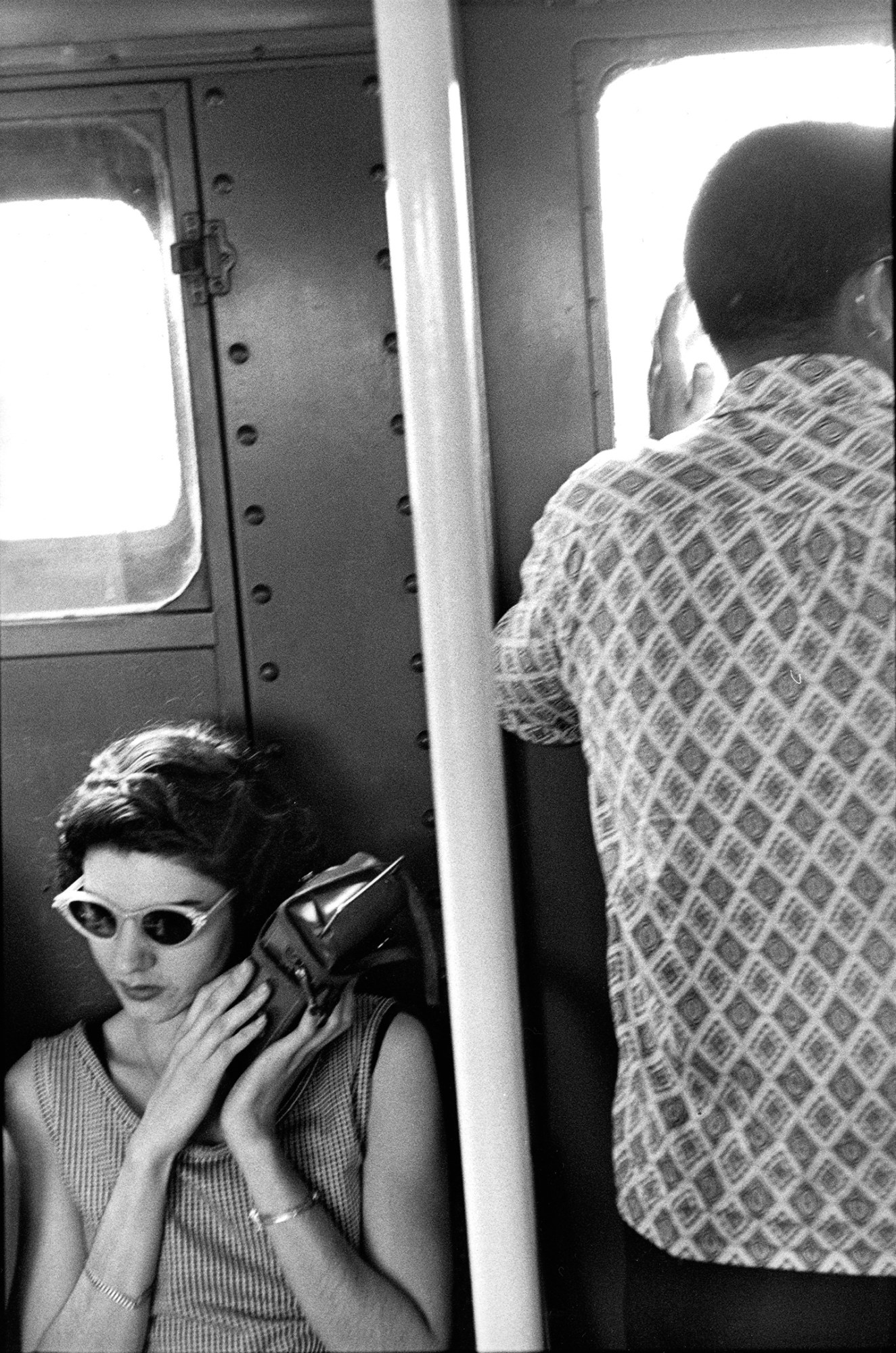

The Way Back concludes with works from Bruce’s 1977 series Subway, a hypnotic collection of chaotic images made in New York’s legendary public transit system when the city was in utter shambles yet devastatingly chic. Filled with a glorious blend of tension and release, these photographs beautifully convey the outlaw spirit of New York in the 1970s. “There was a good deal of time spent going back through my contact sheets, starting from the late fifties through the present day,” says Bruce. “What’s interesting is that through the process of looking back, all the emotion returns. The rhythm of what you were photographing comes back, almost like a musical score. I can see where I may have quit too soon or stayed too long. All kinds of things are working when you’re looking at a contact sheet. The end result is a collection of images that stayed silent then, but speak to me now.”

Bruce Davidson: The Way Back is on view now through September 16, 2023, at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York. The book will be published by Steidl on December 15, 2023.

Credits

All images courtesy of Bruce Davidson and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York