“It’s a fact of human nature that everything is composed of two sides,” says Cassi Namoda, “I always say, for example, that we can’t have joy without suffering.” As bitter as the painter’s words may sound, she sees it as a humble, necessary acceptance of the fact that, for every peak in life, there’s a corresponding trough. “I think it’s a notion that we’ve really lost grasp of in the West — everything is focussed on instant gratification and constantly pursuing happiness,” she continues. “In African life, from what I’ve observed, there’s an acceptance that there’s no blessing without sacrifice. It’s that fundamental balance that I want to convey in my work.”

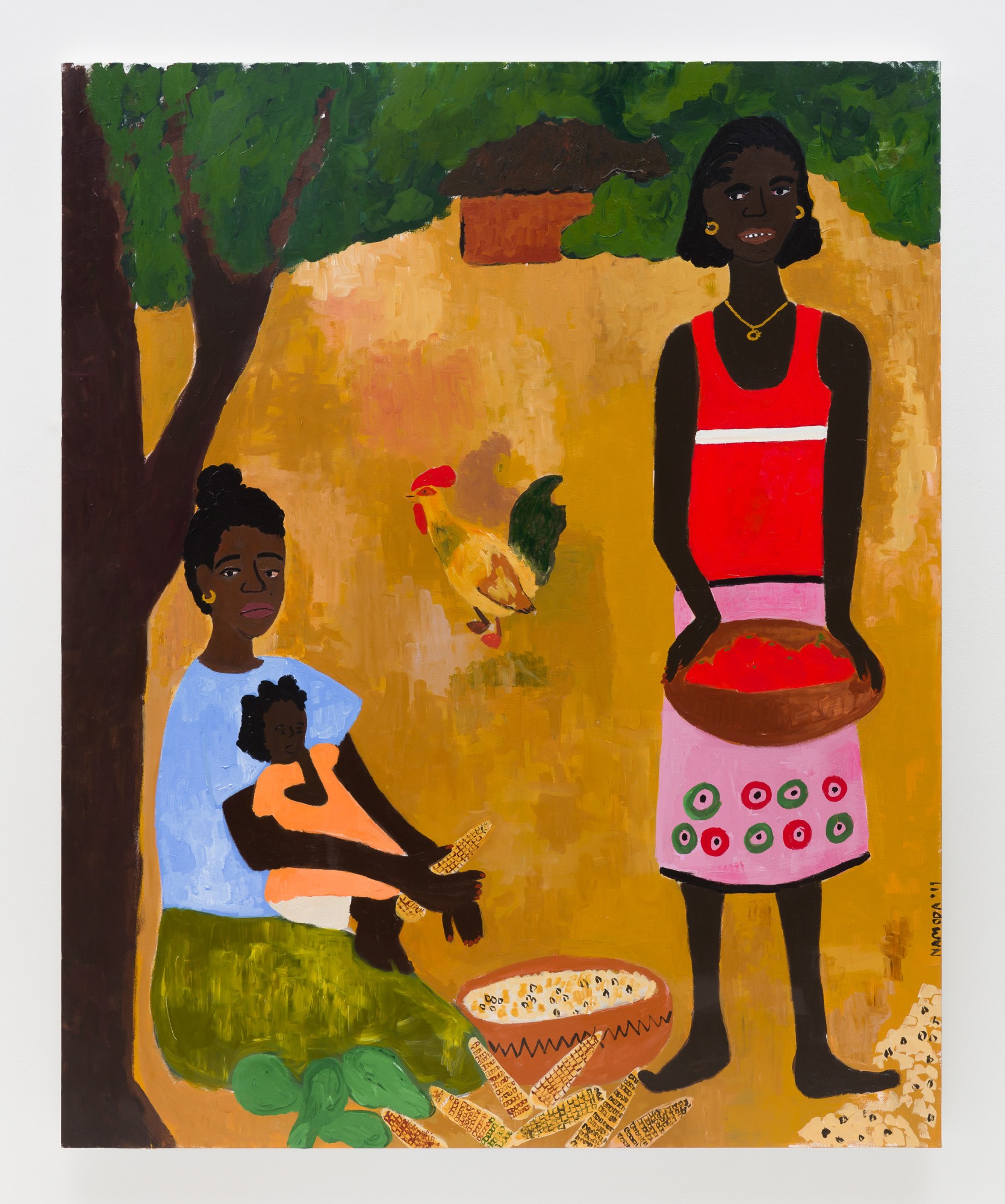

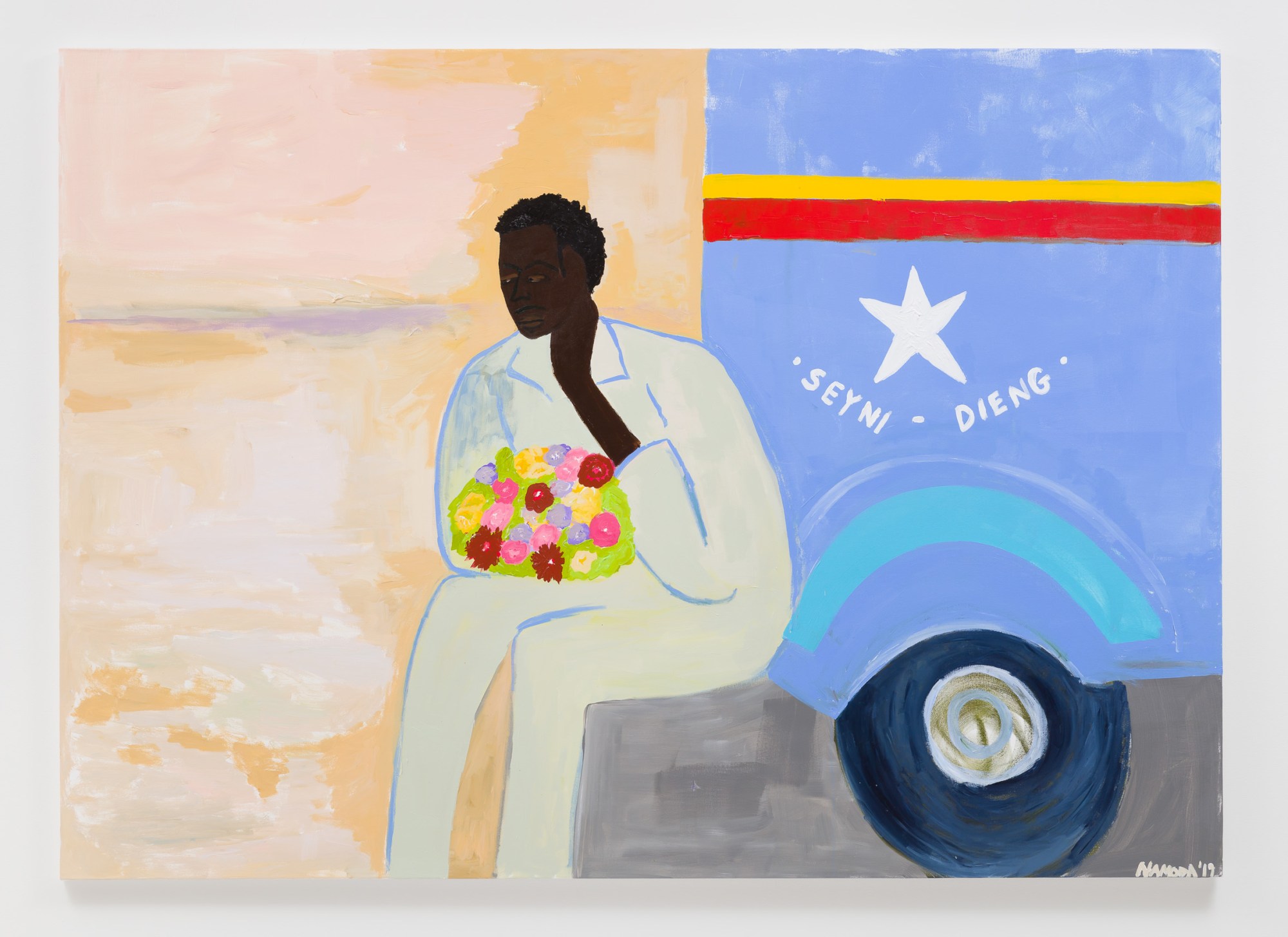

And on viewing the paintings in Little Is Enough For Those In Love, Cassi’s recently opened solo exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in Mayfair, this curious marriage of bliss and pain is unavoidable. In each vignette of life in Mozambique, the artist’s country of birth, the polar emotions cohabit with such familiarity that they seem to seep into the abstracted landscapes in her characters. Dappled terracotta soil painted with loose brushstrokes, for example, hints at layers of colour beneath, like memories we strain to conceal. The same can be said of the human subjects in the works, where a fatigued gaze belies emotions far deeper than what a smile on the lips implies.

Unravelling the cinematic narratives of her paintings is an emotionally testing experience — you’ll quickly find yourself caught in a web of amusement, empathy and sadness all at once. But that’s almost the point; rather than abide by an understanding of emotions as discrete, neat experiences, Cassi confronts us with a world where emotions are simultaneously felt, and all the more authentically for it.

The atmosphere of lived trauma that tinges the paintings is, of course, the product of a particular historical context. After its liberation from four centuries of brutal colonial rule at the hands of the Portuguese by the communist FRELIMO [Mozambique Liberation Front] in 1975, a protracted civil war soon followed. It waged from 1976 until 1992 and cost over a million lives. While the war may not be the direct setting of her work, her paintings implicitly recognise the legacy of residual pain that the population of a post-colonial, post-communist Mozambique have inherited, and the memories of lost ones they carry day-to-day. Yet, far from numbing the capacity to experience joy, this bitterness brings life’s sweetness into relief.

Following the opening of her solo London show, we caught up with Cassi to hear more about how she marries painting and photography, life in Maputo and her experience painting the cover of Vogue Italia.

Little Is Enough For Those In Love is a pretty powerful title. What’s the meaning behind it?

I first saw it when I was in Zanzibar as a proverb printed on a piece of cloth. I don’t really speak Swahili, but I know some words, like ‘love’ or ‘God’. After hearing the translation, its core meaning really struck me, that if you’re surrounded by love and community, you can make do with very little.

It’s something you notice across sub-Saharan Africa. Being in Mozambique at Christmas, for example, it’s isn’t about lavish holiday dinners or an abundance of gifts, but rather community gathering around a table, singing songs, catching up on what everyone else in the family has been up to. There’s real importance placed on just being together. That’s what I’m painting in my work, this idea of really living among one another — whether it’s fishermen interacting, or women picking corn together.

The exhibition is described as an exploration of life and love in Maputo. How would you introduce Maputo to someone who’s never been?

Maputo’s identity is deeply bound with relaxation. There’s a long promenade along the bay where people go to walk, to enjoy the coolness of the day as the sun starts to set, and there’s usually music, too. It makes you ask why we aren’t all living this way…

The architecture also has a huge impact on how people interact; it’s a mixture of baroque, brutalist, art deco: styles that the Portuguese brought with them during colonialism. Prior to FRELIMO and Samora Machel, there was a very Eurocentric understanding of what Mozambique was, after all. But still, this idea of ‘What does it mean to live together?’ is still so central to the urban planning. You really see in the socialist-era blocks, often placed right next to these lavish colonial-era buildings that have since crumbled quite extensively — they’re pretty ghostly.

There’s something about Maputo where no walk of life feels isolated. On the shorefront, the buildings are aligned in such a way that everyone benefits from the breeze of the bay, rather than just allowing that to those that own prime real estate. Go to almost anyone’s place and you’ll see that social privilege has no bearing on your access to fresh air, or to a view of the bay.

It sounds like a very community-minded city. It’s interesting, then, that so many of your paintings focus on individuals.

I studied cinema briefly, and I’m very interested in creating characters. When I’m painting, I think a lot about the nuances of their gazes, and what they can communicate. One of the lifeblood characters in my work is Maria: in this exhibition, she shows up in a downtown setting, the Baixa, which is sort of the red light district. She’s a complex character, and I’m always rediscovering her gaze. I think of her as an expanded metaphor for life in post-colonial Mozambique.

There are also those depicted in ‘The Family Portrait in Gurué’, which I think of in terms of the writings of John Mbiti about the duties that being a member of society entails.

Do you think that there’s a greater sense of having to comply with duty in African social contexts?

Totally. And I think that social duty is always bound with family values. There’s an unspoken consensus that you’re here on this earth to produce a family and carry a lineage forward. And that your children may take on the names on your father or grandfather, so there’s an idea of carrying the legacies of the dead into the present — you can think of it as an iteration of the ‘living dead’.

And the living dead show up in my work, too — that particular portrait is meant to be of my grandfather and grandmother. That’s why I wanted to perform a tea libation at the opening, as a means of activating that lineage in the space. They’re present in my work, but for me to ignore them or not invoke them would be a disservice to their memories.

You’ve also lived in Haiti and the US. How has movement through these different environments affected your work?

My father met my mother in Maputo, and he’s a white man from the US. Growing up, it was quite funny; he would come home from work and complain about guys taking two-hour lunch breaks, to which I would just shrug my shoulders. I needed my father to point out things that perhaps seemed odd from a Western perspective — I don’t know anywhere in London or New York where you could take a two-hour lunch break, for one thing. But in Mozambique, it’s very normal. Time isn’t measured against what you produce in it, so it’s not seen to be wasting time, but rather as creating it.

With regard to Haiti; I was very young when I lived there, but I remember feeling a very strong presence of magic, which really disturbed my mother to the extent that we left to live in the US. Later in life, when I was around 15, I went to boarding school in Benin, which, historically, is a close sister of Haiti’s. There was a very heavy presence of mysticism: it was almost like I’d been taken back to living in Haiti, remembering all of the uncomfortable things about the presence of the unknown.

But there was also a real savage beauty in Benin, and it was also around that time that I started going to the French Cultural Centre in Cotonou to look at photography and watch films. There were also local artists, based between there, Togo and Paris, that would give talks. I think that sparked something in me, and made me want to also transcribe this closeness to the unknown that I’d felt throughout my childhood.

You can sense that in your characters, there’s often something that you can’t quite access behind their eyes.

And that’s very African. I don’t really see it in black communities outside of Africa. I think it often comes down to the fact that so many of the images we see of African people are from the perspective of a foreigner. They may be present in a photograph, but there’s a kind of rupture in their engagement with this white person taking a picture of them.

It also reads like a real stoicism. It reminds me of looking at photos of my late grandmother in Rwanda, and seeing this look of fatigue — this sense that someone’s worked so hard for their whole life, but they have no plans of stopping any time soon, even if they want to.

Absolutely! Though none of the characters in the works in this show have red eyes, I usually paint these tired reddish eyes, and people always ask why. It’s a fatigue from living — but they’ll still walk those eight to ten miles to get to where they need to get to. There’s the story of Josina Machel, who fought in the Mozambican War of Independence and died of exhaustion, after walking for days on end. I always think about her — she was so dedicated to fighting to liberate the country that her last step and breath came at the same time. And I feel like there are so many stories like that.

In many sub-Saharan African contexts, particularly rural ones, living is often a very physical act. But the flip side of that coin is the magnitude of joy and how fully it’s experienced. There’s a relishing of life and a desire to pass it on.

You also look at photography, fusing it with your own memory and imagination. What’s your process of translating photographic images to canvas?

I’ve actually always been more drawn to cinematography than photography, as I find that photographs, while beautiful in their composition, can feel a little one-dimensional. It’s always been more about looking at a photograph as if it were alive, and capturing a frame of that lived moment by fusing it with my own memory or imagination to create a beautiful or interesting moment.

I also look at photography from many different angles, one for them being family pictures. Other times, I’ve used a regional map on Instagram clicked on random villages to see what people are doing there — often they’ll just be taking photos of each other with a new phone. There’s almost no boundary there, it feels like you’ve been transported straight into that environment. And sometimes I’ll look at old tourist books, which is when you’ll get that separated gaze I mentioned — as there’s a white guy with a camera shooting you for a tourism book!

Speaking of how you approach photography in your work, you created one of the covers for Vogue Italia’s photoshoot-less sustainability issue. What was the experience of translating your approach to a fashion image context like?

It was a challenge! It was a pretty tight deadline, and a pretty vague brief — which I guess is pretty typical in fashion. Also, it needed to be a model and she had to be in Gucci… it was a bit of a failure the first time around, as there’s a big difference between modelling for the camera and knowing how to sit for a portrait.

Also, I only paint people that I’ve really gotten to know, so that there’s something deeper behind the face of the character in the painting. I decided to make it more personal, and make the character I was painting Maria. To tie it to the sustainability theme, I included a mosquito, which has previously figured in my work as a mark of something ominous. We don’t think about an increase in parasites as an effect of climate change, but it is a very real threat — we’re currently seeing the worst locust swarms on record across East Africa, for example. They didn’t accept it at first — I think it was a little intense for them — and asked me to produce something a little lighter. They eventually came round, though; I think they realised that an artist’s hand can’t be forced.

Little Is Enough For Those In Love at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery until March 7, 6 Heddon St, W1B 4BT

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery.