The wall of Eric Doeringer’s Brooklyn studio is covered with Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans and silkscreened Flowers, Jasper Johns’ spirited American Flag, and and Ellsworth Kelley’s abstract Green Blue Red shapes. Or at least it seems so until a closer examination reveals the charming imperfections in the artworks. This is because they’re not the originals, which go for millions of dollars at auction, but Doeringer’s own copies, or “bootlegs” of highly-recognizable pieces.

Doeringer started the series in the early 2000s, after moving to New York and being inspired by the vendors on Canal Street, who famously sell knockoff Louis Vuitton and Chanel handbags. Much like a designer bag, a painting from one of the art world’s biggest names can come with a hefty price tag. So, Doeringer set out to make unauthorized copies of some of the most desired artworks out there, which he’s sold for less on the streets of Chelsea, outside galleries featuring the very artists he’s bootlegged, and at shows and fairs worldwide.

“With the bootlegs, I had this idea that I was going to make these things that are cheap, like a knockoff of these luxury goods,” Doeringer says. “But I think over the years I became more interested in these questions of ownership, authenticity, and originality.”

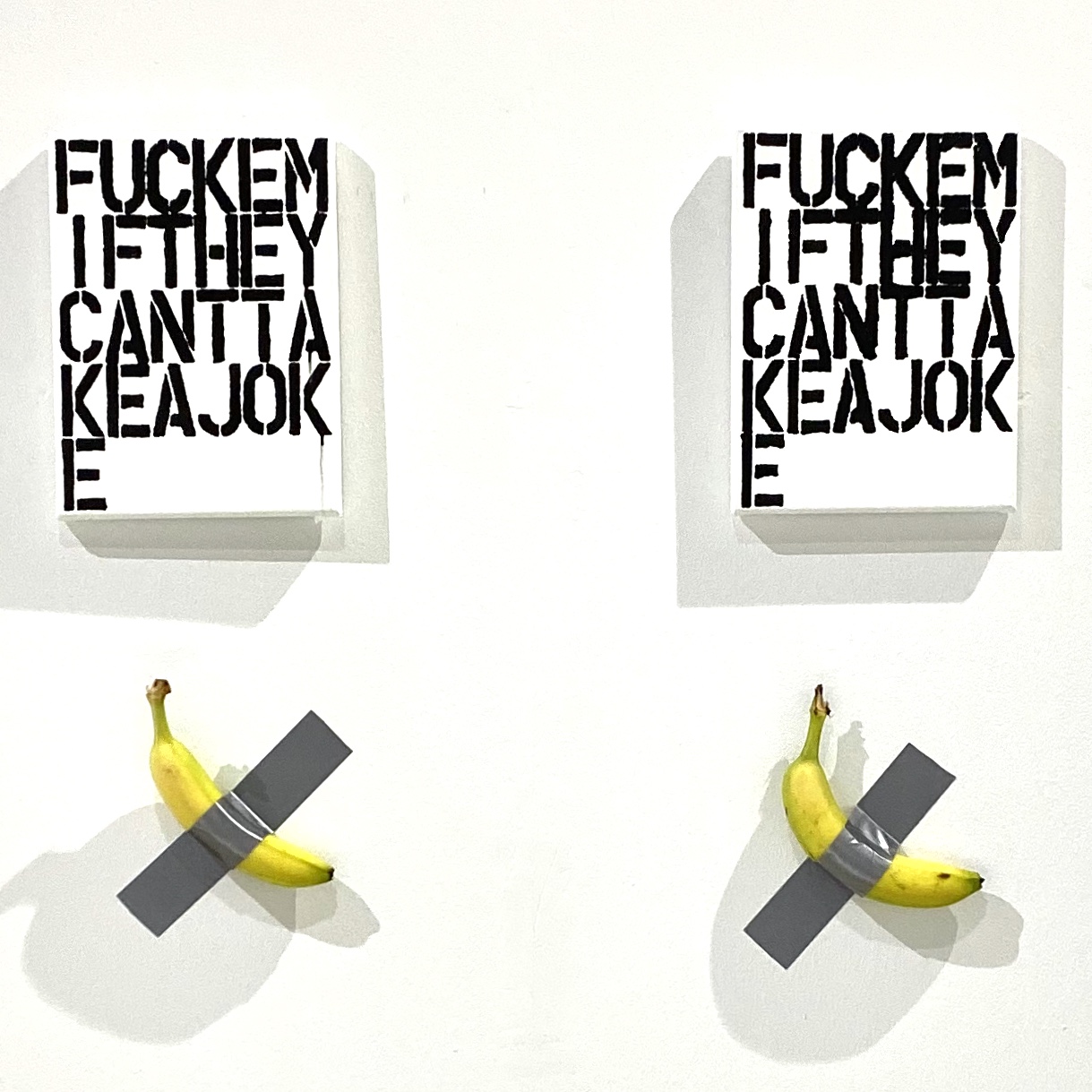

Doeringer went on to bootleg an entire Christy’s auction, which featured a spray-painted, inflatable Rabbit after Jeff Koons’s steel sculpture of the same name. The original sold for a record-breaking $90.2 million, while his was priced at $1000. For Doeringer’s latest exhibition, “Fuck Em if They Can’t Take a Joke,” the artist made over 200 miniature Christopher Wool paintings to be displayed alongside his other bootlegs. The show at Anna Erickson’s Miami Design District gallery stood out amongst its impressive slate of programming during Miami Art Week. And not just because Doeringer added a last minute bootleg of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, the duct-taped banana that took Art Basel by storm. We asked Doeringer all about it.

So, how did this exhibit fall into place?

Anna Erickson, who curated the show and got it all together, is someone I’ve known for a long time. She used to be in New York and I did a show with her in Berlin probably ten years ago. She contacted me and said that she wanted to do something at Art Basel. We talked a bit about what that might be, and I got really excited about doing something on Christopher Wool. I thought that that would be a really good focus.

What is it about his work that made him the perfect centerpiece for the show?

His work is made with stencils, rubber stamps, and silk screens, and he’ll make the same painting multiple times with very minor variations. His work is all about reproduction and repetition. He’ll take a photograph of a painting and then turn that into a silkscreen and then make another painting out of that. They all build off of each other. It just sort of seemed like a really good subject for me to work with and they’re instantly recognizable. Obviously for me, copyright comes up and in his work also — not that there’s no copyright there, but it’s very thin. They’re made to look like they’re mass-produced with a stencil you buy at the hardware store. I think both in his case and in mind we made the stencils ourselves, but they have the look of being something that was made by your landlord or something.

It’s called ‘Fuck Em if They Can’t Take a Joke’ and that was taken from one of Wool’s most famous paintings. It’s a call to that, but also hoping that the artists that I’m copying could take it as a joke. I’ve been lucky not to have a lot of legal problems, but a few artists sent me cease and desist letters. You know, it’s kind of like, c’mon guys…

I saw that you replicated Cattelan’s banana as well.

Yeah! I saw that at the opening and was like, ‘We’ve got to put that in the show.’ It was such a great piece because it’s obviously something that anyone could make, but it’s a Cattelan and it’s this piece that everyone was talking about. What makes his banana worth $120,000 and mine worth $1,000? I would posit that my banana would have more value than yours would if you made one. And yet it’s the same thing. If we each put a banana up on a wall in a museum, no one would know whose was whose. I think what was funny about seeing the media reaction to that piece was there were all of these headlines about the $120,000 banana, but you’re not actually getting the banana. You’re just getting a certificate that’s got instructions and says you can put it on the wall and change it out. You’re buying an idea, and it’s not something you can copyright. Apparently one of the people that bought one came to the show. And I was like, ‘You couldn’t sell him one? That’s less than his sales tax actually.’

Going back a bit, can you tell the origin story of the bootlegs?

I first started selling them on the street in New York in 2001. I was pretty new to the city at that time. One of the things that I was excited about was Canal Street. There were all of these guys or often women selling fake designer handbags. I was really interested in the way that these things were sold and also that there were different levels of quality. For a couple hundred dollars you could get one that was made in the same factory in China, for $100 you could get one that looked pretty good but wasn’t high quality, and then for $50, you could get one where instead of the letters LV it had the letter P on it.

Obviously, it was making these luxury things available to people who couldn’t afford them. I just thought that art is this luxury thing and status symbol. There are people who’d love to own an Andy Warhol, but don’t have a million dollars. I could do this and sell some fake art on the street. I first envisioned it as a one day project and I spent the summer making works by 30 different artists. I was out in Chelsea, so a lot of people came by, but I still had a lot of paintings left. Might as well do it again next week. I saw it as not exactly a critique, but about the art market. If you look back in about 50 years, it will be this snapshot of who people are into as artists. I liked the performance aspect of it and I liked that I didn’t have to go through a gallery. It was very liberating in a lot of ways and I just kept doing it for the next few years.

A year ago, Adam Cohen who had collected my work and who is an art dealer, contacted me and he was like have you ever thought of bootlegging an auction? That was my return to making these small paintings, multiples, and it seemed like a good time to do that. We did the show at the same time as the auction. You could go to the show and see the originals or you could see the copies and choose where you’d like to spend your money. Adam and I are going to do a show in LA in February, which is what I’m working on now and that’s going to be the Broad collection.

What was the first bootleg you’ve ever made?

I don’t actually remember what the first one was because I always envisioned it as being a group. When I first went out it was people like Damien Hirst, Elizabeth Peyton, John Currin, Barbara Kruger, and Christopher Wool, those were some of the first ones.

You mentioned that you’re making a statement to the art world, but what is it specifically that you hope your work will say, or do, or make people feel?

Well partly it’s a democratic impulse. These things are unique, super expensive objects, and why not make something that everyone can have? I am also interested in the relationship between the original and the copy, especially in the art world. What are we buying? What do we value? What do we think is sacrosanct? What do we think are we able to interpret? When I first started making the bootlegs it was when Napster was going through legal issues. I see my work as tying into the rise of the internet and digital culture, and the fact that we can share images, music, and movies so freely. Ownership as a concept is dead in a way and it has become this kind of free for all. I’m interested in reflecting that back in a fine art way. But also this idea that no two copies are the same. Even if you download a song, copy it, and send it to your friend, there’s going to be little errors in there or something that’s imperceivable, but still different.

What’s nice about this show in Miami was we had pieces from three different years, so there were little variations in the colors or the inks. Each one is different and they are handmade by a person. I like that play between the mass-produced copy and this handmade object. I had this idea that I was going to make these things that are cheap, like a knockoff of these luxury goods. But over the years, I became more interested in these questions of ownership, authenticity, and originality. I continue to find it to be very fertile territory. And not that I wouldn’t eventually do something else, but I continue to find new and interesting ideas. Not just like, let me make a soup can instead of an electric chair.