A few years ago, when Isa Mazzei was working as a camgirl, she decided that she had finally had enough of hearing every shitty stereotype of sex workers under the sun.

“Even people who loved and cared about me! They would say: ‘Oh, but you’re so normal’ or ‘Oh, but you went to college.’ Isa rolls her eyes under a heavy fringe. “It was eating away at me. I realised that the representation of sex workers in the media was more than just an annoyance. It was affecting my life and the lives of other sex workers in dangerous and violent ways.”

Isa realised that the only way for these stereotypes to change was for someone within the sex work industry to represent what it’s actually like to work. The frustration and realisation led her to put pen to paper and write the screenplay for last year’s CAM, a critically-acclaimed B-movie horror about a camgirl whose identity is stolen online.

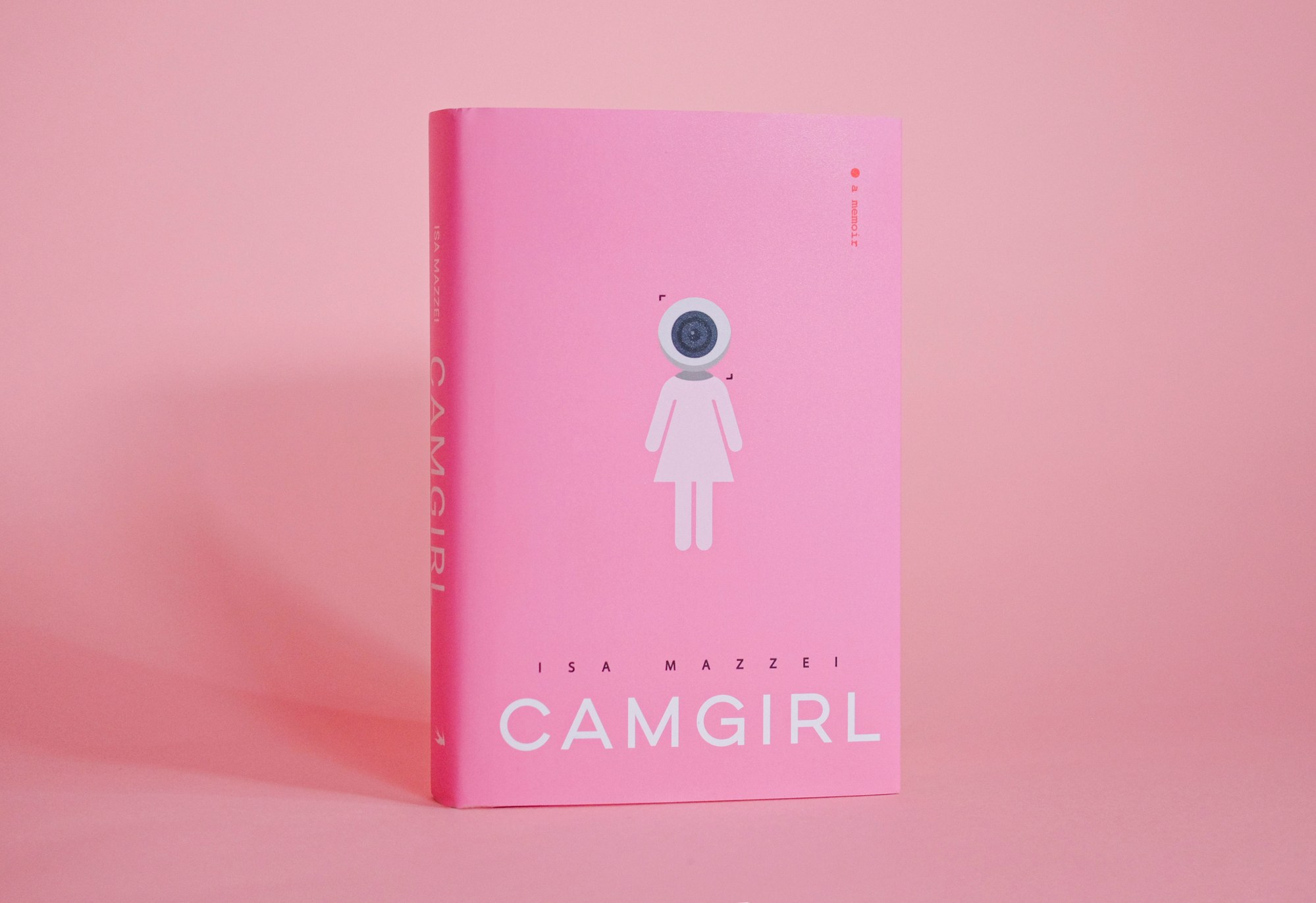

While Isa used her own experiences to create the character of Lola, she felt like she had more to say without the protective guise of writing fiction. The result is her new memoir, Camgirl, which takes us through Isa’s journey from newbie camgirl to a star of the format. It’s an often funny, sometimes heart wrenching, behind-the-scenes look at what sex work is really like.

Over webcam (of course), we speak to Isa about how she became a camgirl, how sex work let her reclaim her body and how writing allowed her to process her trauma.

Morning, Isa! Can we start with how you became a camgirl? What was going on with you at that time?

I was a sugar baby before I was a camgirl. At that time, before I’d even met my sugar daddy, I wanted to get into sex work in some way. I was thinking of stripping but I decided to try getting a sugar daddy first. At the end of our time together, I felt like I wanted to do something different. My sugar daddy suggested camming. He showed me the first camgirl I ever watched and I was immediately entranced by it. I loved that it was online and I loved the creative freedom that it allowed. Every cam model was in control of their own space and show and costumes.

How did you go from your first camming experience to becoming a star of the industry?

You know, I was really aggressive from the beginning. I’ve always been very ambitious and I decided that if I was going to be a camgirl, I was going to give it everything. I did a lot of research before I started: I thought of a brand, I trademarked my name, I got a logo designed and a website. I was very deliberate. I figured out which hours would be the most lucrative to work during and which nights were the best to take off.

When I started I was so nervous. I didn’t know the terrain yet, so even though I was prepared on paper, I was still figuring out what it takes. But I found it was really fun and I knew I wanted to do this. It really pushed me to constantly have to be better with my craft.

It seems like your journey as a sex worker parallels your journey as an artist.

For me, art is about exploring myself and how I relate to the world around me. I put a lot of that into my art as a writer, and when I was camming it was the same thing. I did a lot of arts and crafts on my show. Just getting to have a creative outlet was really exciting and validating because I felt like my artistic expression was appreciated by so many people in so many different ways. It really became a process of self-exploration, which is what a lot of art is about.

Do you think people are starting to see sex work as art?

I think so. The response to CAM gave me hope. People are starting to take sex work more seriously and understand the work, artistry and legitimacy of sex work. That’s part of why it’s so important to me to have my story out there. I’m just one voice of many and adding to the point that we’re all trying to make: that sex work is valid, sex work is legitimate and sex work is work. It’s important that we respect sex workers like we respect workers of any profession.

In the memoir, you write about how being a camgirl changed your ideas of control and power. Can you talk about that process?

Growing up, I never really felt like I had much agency over my own body. As a childhood sexual abuse survivor, I had that control taken away at a really young age. Just existing as a woman growing up in this culture, it was a constant barrage of catcalls and getting hit on inappropriately by old men and feeling pressured into sex. I felt like I didn’t get a say over my own body. I had the media telling me my body was gross and my trauma telling me my body was gross. It imbedded this deep cycle of shame and feeling out of control.

Sex work was the first place where I felt like I regained that. A lot of it had to do with dictating the rules — like, if you want to look at me, this is going to cost you and if you want to touch me, this is going to cost you. I was able to set those boundaries and enforce them myself. It was a really healing place for me to feel in control of my own body and what could and couldn’t be done to my body. That was really transformative.

Did you find revisiting that mindset cathartic?

Writing my book was a process of learning to forgive myself. Emotionally, it was really difficult to take myself back to those places and to be honest about some of my own behaviours. I think for most of my life I’ve been carrying a lot of shame from my childhood. A lot of feeling like everyone was judging me and hated me and lots of self-hatred for the choices that I made. I think that writing the book was such a clear lens for me to process this trauma. I was able to recognise so many of my own choices as self-protective responses to trauma, so that was a really important way for me to forgive myself and let go of all the things I was still holding on to.

Even though your experience is very much your own, it sounds very relatable.

Yeah, I think that a lot of the ways we talk about sexual behaviour is gendered and unfairly so. I remember being in high school when someone first pointed out: why is a girl a slut, while a guy is a player? I thought about that a lot because I was someone who was called a slut in high school and I was someone who tried to reclaim that but found it difficult to do. I felt really caught in this cycle where women are constantly sexualised but also told not to be sexual. I think it all goes back to the idea of bodily agency. I think one of the reasons we find women who have control over their sexuality threatening is because we live in a society that doesn’t let us decide ourselves if we’re going to be sexualised.

What was so empowering about camming was deciding when I was going to sexualise my body and when I wasn’t. I was making those choices for myself in front of an audience every day. I think that was also really healing: learning that I didn’t have to be a sexual object just because someone outside of me was trying to sexualise me.

I really enjoyed the parts of the book that were insights into the behind-the-scenes of camming. Why was that important for you to include?

Because I still get people — primarily women — who are like, “I wish I could just take off my shirt and make millions of dollars”. It’s so funny to me because camming was the hardest job I’ve ever had and it challenged every single part of me. You have to run a social media brand; you have to run a website and a business; you have to do marketing and be a performer and do make-up and costumes and know lighting and camera work. You’re constantly managing so much at the same time and I think those skills go neglected and are overlooked. It’s such a shame.

What’s something you learned as a camgirl that you still use now?

I learned a lot about existing online and the idea of an online persona. There’s a boundary there and it’s important to have that boundary. That’s kind of the paranoia I wrote about in CAM: losing control of this person you’ve put online that is you but isn’t you somehow, and getting lost in online validation. The most important lesson was to derive my validation from who I am in the real world and not online. I think a lot of non-camgirls do that too. Your life isn’t your Instagram likes.

‘Camgirl’ will be published on 28 November in the UK.