The last week has seen yet another chapter in the exhausting and seemingly endless narrative of modern-day transphobia. This time, it was the widely publicised launch of ‘LGB Alliance’, a new group which aims to provide a platform for gay men, lesbians and bisexuals who are concerned about ‘gender extremism’. Although such people certainly exist, it’s telling that a significant proportion of the replies to the group’s announcement took the form of “I’m straight — but I think this is bloody brilliant!”

The LGB Alliance itself is not really worth discussing. Its ideas are so obviously bigoted that there’s no benefit in debating them and, besides, it’s not really that big a deal. “I’m not particularly fussed about it,” says Christine Burns MBE, trans activist and author of Trans Britain: Our Journey From the Shadows, the first comprehensive trans history book to focus on the UK. “It’s just the latest in a long stream of pop-up organisations. They keep churning them out. These groups appear as though they’re well supported when essentially it’s just the same set of people, again and again.” But, in its attempt to sow division, the group does raise some interesting questions about the nature of the relationship between the trans and the cisgender queer community, what it has been in the past and what it needs to be now.

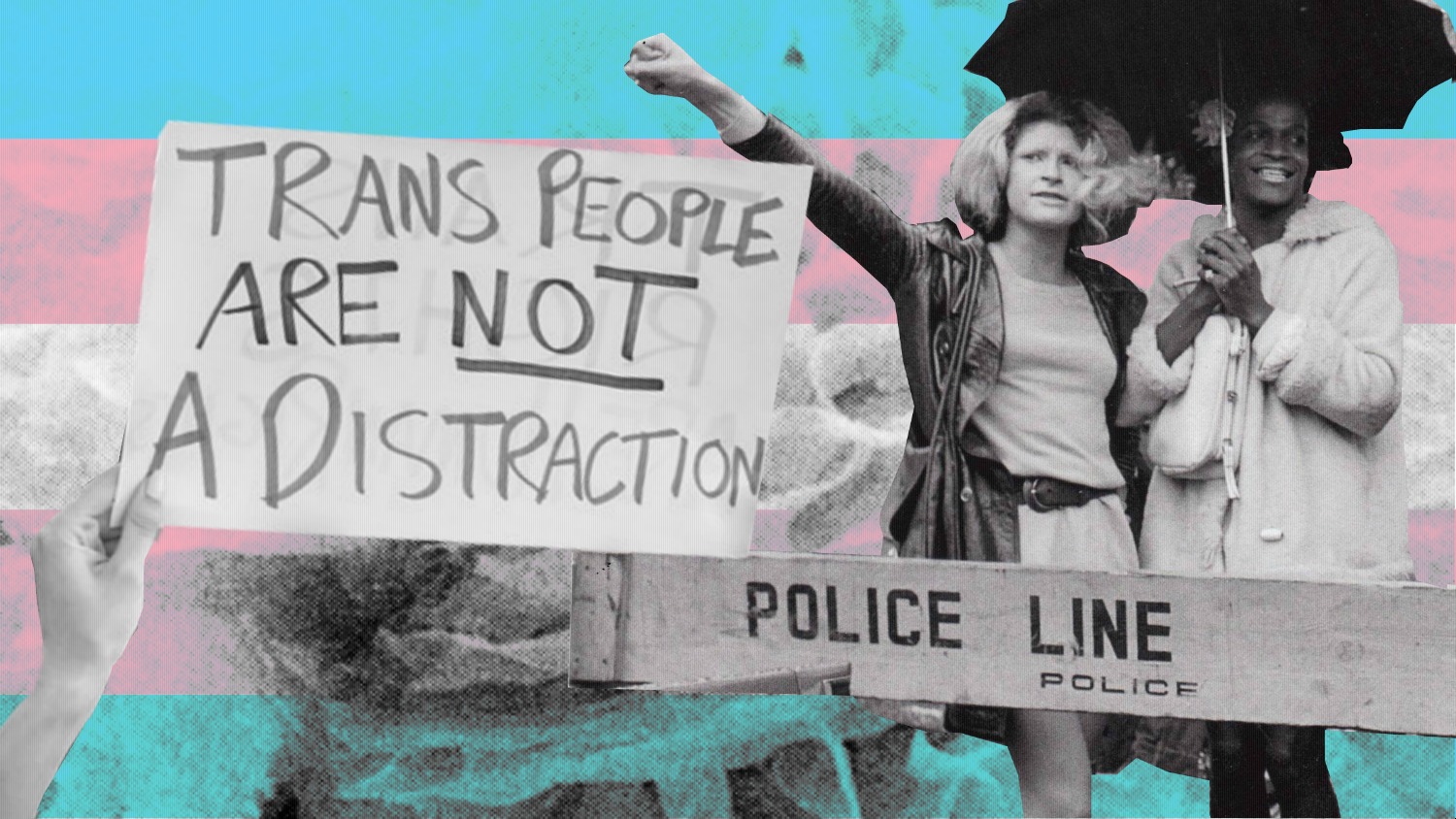

It goes without saying that trans people have played an integral part in the modern queer liberation movement from the very beginning. Stonewall, still considered the most significant event in the history of gay liberation, would not have happened without transgender and gender non-conforming people. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson (both of whom were recently commemorated in an excellent Netflix documentary, The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson) arose as notable figures, and were instrumental in organising the movement which followed. One of the saddest facts of queer history, however, is how quickly trans women were sidelined in the post-Stonewall movement.

In 1973, just three years after the riots, Rivera took to the stage at New York Gay Pride and was met with boos and jeers from the largely cis, white and middle-class audience. The result is one of the most incendiary speeches of the 20th century, as she calls out the audience for their apathy, their inaction, their betrayal of their trans siblings. “I have been beaten, I have had my nose broken, I have lost my job, I have lost my apartment for gay liberation — and you all treat me with this way?” she demands. “What the fuck is wrong with you all?” Sadly, this is still a pertinent question. Sylvia and Marsha are rightly revered today but it’s important to remember that the history of cis gay men and women fucking over trans people is just long as the history of solidarity. Perhaps cisgender queers owe more to trans people than vice versa.

When I speak to Dr. Justin Bengry, Lecturer in Queer History at Goldsmiths, I am hoping to find historical evidence to justify the need for cis queer solidarity in the present. He doesn’t quite give it, however, and instead argues that history is not where we should be looking for answers — a bold stance for a historian. “If we want to find a rich and extensive history of organised collaboration between cis gay and trans activism in our past, I fear we will be largely disappointed,” he says. “We need to look upon the past and challenge ourselves to do more and do better. The collaborative and intersectional work we need to do is in the present. We should reject transphobia not because someone in the past might have done so, but because it has no place today among decent people.”

Thanks in no small part to the iconic status of Sylvia and Marsha, the discussion of the role of trans people in queer liberation has often been American in focus. According to Christine, who has been a key figure in trans politics for several decades, the parallel history in Britain is just as complex. “TERFism only really started in the 1980s,” she says, “with American writers like Janice Raymond and her book The Transexual Empire, which was really vicious. If you go back to the 1970s, most feminists were pretty cool with trans people. We existed in those spaces, and we existed in gay and lesbian spaces too because we all needed to. We were such a small group of people that we had to get on together and not be freaked out by each other.”

During the 1970s and 1980s, there wasn’t much organised collaboration between transgender and cisgender queer people in Britain, Christine says. “Not formally anyway — trans people weren’t really organising in that sense. We were pretty crushed and on the bottom of the pile, even as far as the gay and lesbian community were concerned. There was tacit support — for the most part we were mutually respectful — but it wasn’t very overt. But then, during the 1990s, we had so many legal successes that we didn’t really need cis allyship.”

In light of the rise of the TERF movement, this is no longer the case. Cisgender queer people today should support trans rights because it’s self-evidently the right thing to do, much like opposing racism or misogny or any other form of bigotry — it really is that clear-cut. But, on a more self-interested note, it’s also worth considering that the line between transphobia and homophobia is very thin. “Gender non-conforming cisgender woman are right on the frontline of this,” says Christine, “it’s them who get dragged out of toilets and attacked by men, wanting any opportunity to follow a woman into a toilet to say ‘I don’t think you’re a woman’.” The last few years have seen a number of cases of butch women being subject to transphobic harassment in bathrooms, despite not being trans. Who would have thought that a movement based around the rigid policing of gender expression might end up having negative consequences for gay people?

For further evidence that transphobes are not allies to the ‘LGB’ community, many high-profile TERFs have also recently made biphobic comments. Take writer Julie Burchill, for instance, who claimed “bisexuals aren’t oppressed because they can SWITCH. Bisexual just means GREEDY/TWICE THE FUN. I have as much sympathy for them as I do bulimics in a word of starvation.” Aside from the lazy and ignorant biphobia, it’s almost cartoonishly evil to brag about not feeling any sympathy towards people struggling with bulimia — a disorder which is, incidentally, disproportionately prevalent amongst LGBT people. It’s not altogether shocking to discover that the sort of person whose entire raison d’être is the obsessive bullying of a marginalised group might prove to be cruel in other areas, too. These people aren’t our friends.

The transphobic hatred of queer culture is also apparent in the attitude of TERFs towards drag — an art form which has historically been, and continues to be, practised mostly by trans women and cis gay men. The popularity of Drag Race also makes it about as close to a universal queer cultural touchstone as we’ve ever had — ‘the gay football’, as many people have described it. And yet TERFs, by and large, despise drag. Last week, a transphobic conference featured a segment dedicated to the Orwellian horror of “Drag Queen Story Time” — a series of events in which drag queens visit local libraries and read storybooks to children. One attendee, journalist Sonia Poulton, huffed: “they think they are woke; I think they are sexualising children with gross caricatures of women.”

Noted TERF Kathleen Stock, meanwhile, recently wrote an article for right-wing magazine Standpoint, in which she compared drag to blackface. You have to give credit where it’s due for someone managing to be offensively stupid on so many different levels. The point of all this is, transphobes are concerned about the erasure of queer cis people right up until the moment we contradict them, at which point they won’t hesitate to attack us. There are gay and lesbians transphobes, sure, but these people are letting the side down; their bigotry isn’t any more valid just because it’s informed by their identity. We shouldn’t afford these deeply pathetic people any respect.

In her essay collection Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino writes about how solidarity has come to be defined by identity. “The internet can make it seem that supporting someone means literally sharing in their experience — that solidarity is a matter of identity rather than politics or morality… under these terms, instead of expressing morally obvious solidarity with the struggle of black Americans under the police state or the plight of fat women who must roam the earth to purchase stylish and thoughtful clothing, the internet would encourage me to express solidarity through inserting my own identity.” This would be comparable to a cis queer person saying, “I support trans people because I understand what it’s like to be oppressed” or, perhaps, “because I know what it’s like to be gender non-conforming.” But we don’t actually need to do that. To use Tolentino’s words, rejecting transphobia is “morally obvious” in itself.

But on the other hand, as a cis queer person, I believe that I am part of the same community (in the broader LGBT sense) as those who are under attack. Opposing transphobia is about solidarity, sure, but it’s also about recognising that trans people aren’t an entirely distinct entity. It’s impossible to untangle trans and cis queer history; we’ve faced many of the same historic struggles (the AIDS crisis disproportionately affected trans women and cis gay men, for instance), we share many of the same cultural touchstones, and we still inhabit many of the same spaces. For all that sex and gender are separate things, the ‘LGBT+’ category has value. The attempt to tear it apart is a divide-and-conquer tactic (which Christine argues is directly inspired by the right-wing evangelical movement in the US) and we should resist it. With transphobic hate crimes on the rise, there’s a moral imperative for cisgender queer people to use the greater privilege we have, to speak up and show solidarity. We need to start viewing an attack on one part of our community as an attack on the whole.