As people of colour and minorities, we always carry a double burden: the burden of building our careers and the burden of navigating systemic racism, the powers of oppression that are directed at us. When I hear complaints from those who benefit from white privilege about how complicated diversity is, I think to myself: If we can carry the burden of racism past and present, you too can carry the burden of diversity.

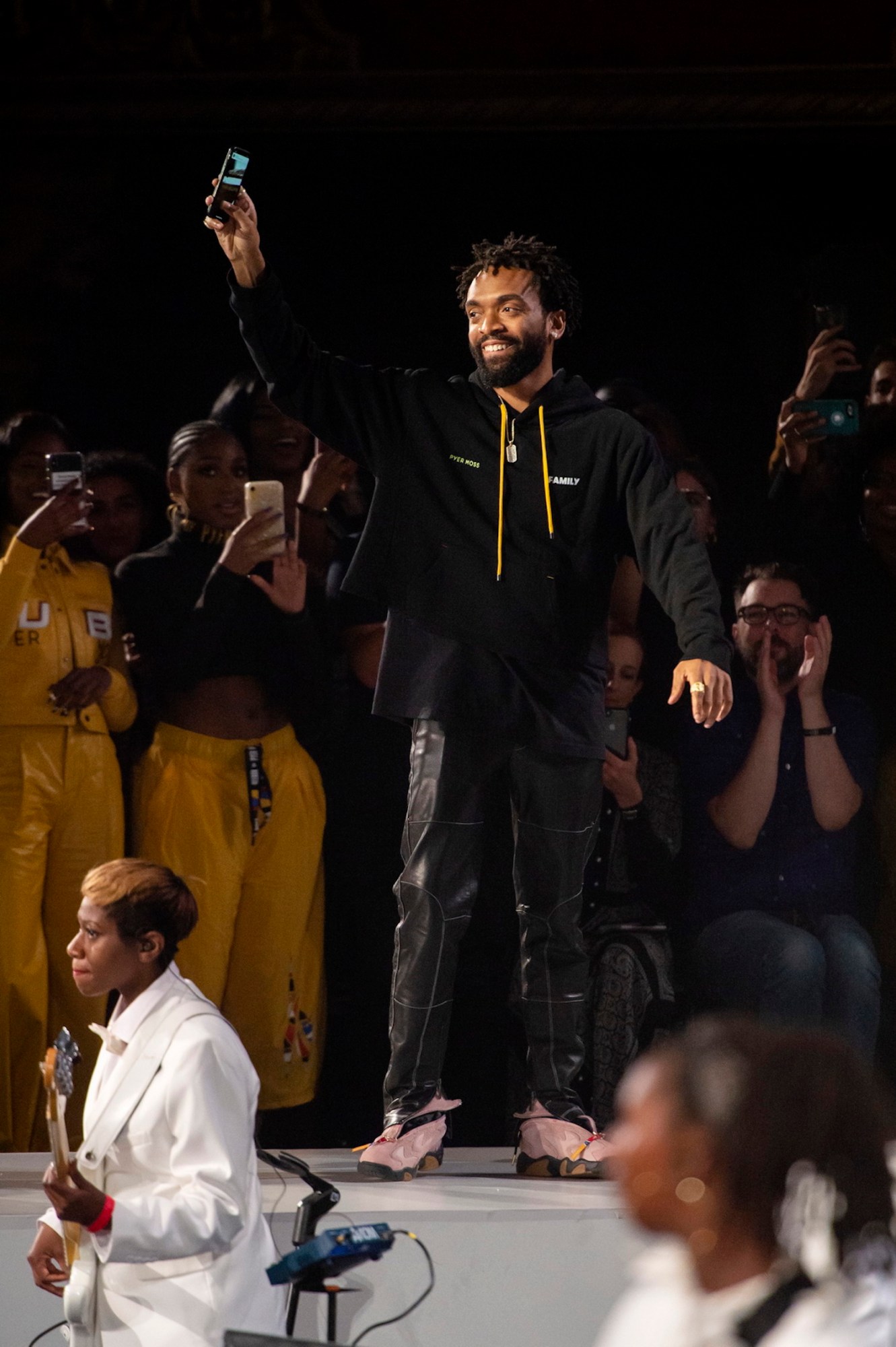

Last week, African American designer Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss voiced his disappointment on how Business Of Fashion handled his role in the creation of their current print issue on diversity. It all started when the designer was invited to BoF’s yearly event, Voices. They’d asked him to participate as a guest speaker in a one-on-one conversation with long time model, agent and diversity advocate, Bethann Hardison. While Kerby was on his flight to the UK though, his segment was turned into a group panel. He participated in the event, but felt that the other panellists had their own unique narratives and histories which warranted their own separate stages and conversations, the same solo stages that all the other white designers have received for years.

A few months after the Voices event, BoF’s editor and founder Imran Amed contacted the designer to inform him that he would be one of the three covers for their upcoming diversity issue. After extensive communication, the two met in Paris where the designer let the editor pick his brain on a list of diverse people to include in feature. Kerby opened up about current and future projects, but shortly after the meeting he was dropped from the cover. “I knew I was being played for info,” Kerby claimed afterwards.

Despite this, the designer accepted an invitation to attend the BoF 500 Gala, as he had been added to the magazine’s list of the 500 most influential people in fashion. The use of a black choir to greet the guests raised questions around appropriation; Kerby walked out and, later via Instagram, asked for his name to be removed from the list. Imran Amed later issued an apology and promised to sit down and have a conversation with the designer.

“Homage without empathy and representation is appropriation,” Kerby said in the statement shared via Medium. “Instead, explore your own culture, religion and origins. By replicating ours and excluding us — you prove to us that you see us as a trend. Like, we gonna die black, are you?”

Diversity is a process as much as an end point. It isn’t just one thing. Diversity has climbed and flatlined and waned over the years.

The fashion industry has had many different kinds of diversity drives in the past, some of which have been based around simply ticking boxes, and some have been more honest, that have come from designers’ and editors’ effort to reflect their creative visions. Advocates like Bethann Ardisson and Naomi Campbell have long acted as pillars of diversity on the catwalks. But diversity is a process as much as an end point. It isn’t just one thing. Diversity has climbed and flatlined and waned over the years.

Some — mostly white — magazine editors have even told me they view the current move towards diversity as a trend-based business move. What worries them is that brands, galleries and institutions are approaching it in a superficial manner, while the others who simply show reluctance by keeping their catwalks or campaigns as white as possible are hoping it all just goes away at some point. Putting people’s race and culture on the same level as hemlines and floral prints highlights how far some people still have to go, and their vested interest in maintaining systemic racism and the power it confers them. Privilege is socially constructed to benefit members of the dominant group; it allows one to judge what is appropriate and acceptable. Deciding that dreadlocks are not suited for a work environment is arbitrary and ludicrous. Racism is not just about African or Asian features, but the symbolic and negative connotations one dominant group can attach to them.

I sometimes like to replace the word diversity with simply the idea of living with difference. How willing or equipped are you to live, work and create with someone who is different from you? Because so far, ‘the other’ has been dealt with either with exclusion or fetishisation.

But the industry is forming its allies; like Gucci, who after their blackface scandal announced an investment of £9 million into a new Changemakers scheme. Prada too, after another controversy, has established its own diversity council, co-chaired by Oscar-nominated director Ava DuVernay. They have shown commitment to change things not just on the catwalks but also internally in their company. It’s not enough to make cosmetic changes on the catwalk and in the campaigns if the boardroom and the design teams are predominantly white, which is what lead to their poor judgment in the first place.

A London-based African designer I spoke to, who wished to remain anonymous, told me they would rather focus her energy on something positive, on their work and building their brand and doing it for future young black creatives. “Their world of systemic racism is dying,” they said.

We cannot be held back or attempt to fix those who revel in hypocrisy or cynicism. As the late Toni Morrison said: “Racism is a big distraction” — something that takes the focus away from what a person of colour might achieve or want to achieve. New media offers opportunities for self representation and people of colour and marginalised communities must harness that, create their own platforms and events or self-publish. It’s not enough just to call out, be content to be included on someone else’s list, it’s time to take some power back.

Rihanna is a great example of this energy. This season, she created an alternative to Victoria’s Secret with her Savage x Fenty show during New York Fashion Week, which included all races, genders and disabled women. She is not only the first designer in three decades (the last one was Christian Lacroix) to receive a full LVMH backing in creating her own fashion house with stores, fragrances and beauty, but a young black business owner whose vision of inclusivity has become highly lucrative.

The younger generation of creatives benefiting from white privilege will have to play a role in bringing about a new fashion system where difference is valued and celebrated — not exploited or excluded. Kerby Jean-Raymond showed great integrity and professionalism when faced with adversity — even while carrying that heavy and hindering double burden.