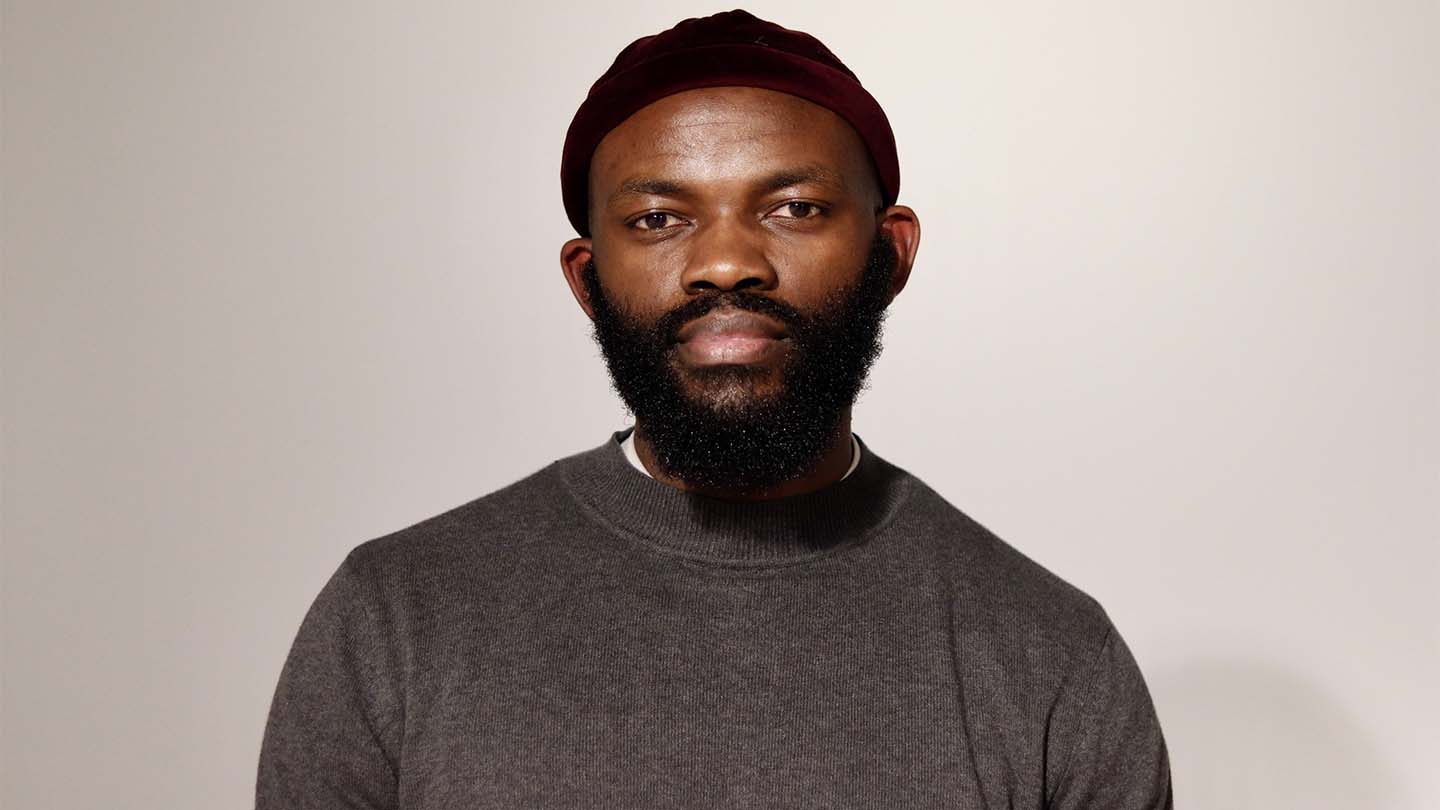

What is masculinity? Dominating the world around us, from Trump’s twitter outbursts to deadly gun violence, from male suicide rates to incels on Reddit and 4chan, masculinity is perceived to be ‘toxic’, ‘fragile’ and ‘in crisis’. In a new book, writer JJ Bola exposes masculinity as a performance that men are socially conditioned into. Using examples of non-Western cultural traditions, music and sport, Mask Off shines light on historical narratives around manhood, debunking popular myths along the way. He explores how LGBTQ men, men of colour, and male refugees experience masculinity in diverse ways, revealing its fluidity, how it’s strengthened and weakened by different political contexts, such as the patriarchy or the far-right, and perceived differently by those around them. At the heart of love and sex, the political stage, competitive sports, gang culture, and mental health issues, lies masculinity: Mask Off is an urgent call to unravel masculinity and redefine it.

Read an extract here:

In the modern era, fierce debates are taking place around masculinity, femininity, and the gender binary itself. Some argue that masculinity is toxic, fragile and in crisis, while others argue that increasing debate on it proves that masculinity is to be protected at all costs by those attempting to destroy it. Masculinity and femininity, as traditionally understood, are traits or characteristics that we exhibit on the basis of our sex, but it remains distinct from the definition of the male and female biological sex.

Judith Butler argues that ‘gender is an identity tenuously constructed in time . . . through a stylised repetition of acts’, highlighting its performative nature. While gender is not the same thing as masculinity and femininity, gender roles largely tend to fit into masculine and feminine roles. Many have argued that this idea of gender as performative can be extended to masculinity and femininity: that we perform specific ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ roles and acts which continuously validate our sense of our gender: for example, being strong makes us more of a man, and being weak makes us more of a woman.

The many things that we are told about manhood and masculinity are actually dangerous to us, as boys and men, and to those who are close to us, including women. What are the examples, then, of how masculinity is different depending on location and culture in the world? In places like Nigeria, Uganda, India, and Congo, that men hold hands as a sign of brotherhood, friendship and affection. Throughout history there are various other examples, such as societies that are largely matriarchal and matrilineal – meaning societies where women held positions of power, and were not considered to be inferior, or weaker than men, and lineage and inheritance was passed on through the woman. That’s not to say those societies manifested in the same way that a male-dominated or patriarchal society does in terms of oppressive structures: rather it means that their women were in positions of power and not rendered a marginalised group.

Feminist writer and researcher Heide Goettner-Abendroth argues that matriarchal societies should not be seen as mirror images of patriarchal ones; they do not have patriarchy’s hierarchical definition. Matriarchal societies are socially egalitarian, economically balanced, and politically based on census decisions (democratic). They were created by women and founded on maternal values.2

There are still matrilineal societies around the world. For example, the Minangkabau ethnic group – the world’s largest surviving matrilineal society – in West Sumatra, Indonesia, where land and property is inherited through the daughters, the children take their mother’s name, and a man is considered a guest in his wife’s home. It is a complex and distinct societal and political structure where women’s agency is strengthened and empowered, rather than suppressed as in many places elsewhere in the world.3

Today, we are still caught up in the idea that the colour pink is for girls and blue is for boys (consider how popular internet gender reveal videos are), so it can be hard to imagine that make-up or high heels – ‘feminine’ things – were in some instances originally designed for men, or were things that men enjoyed. During the early seventeenth century, high heels were brought to Europe from Persia, and men typically wore high heels as a display of their upper-class status. The shoes were expensive, and so to wear them was to show that one had material wealth and financial status. Heels also made men look taller and more athletic. There is a famous portrait of King Louis XIV, of France, standing boldly in full-length tights, white shoes with a thick brown heel of approximately three inches.

Ultimately, masculinity is a performance; that is to say, it is acted out in a way that reinforces the widely held view of what is normal for those born as male. That’s not to say that masculinity is in and of itself destructive – but there is of course, the issue of toxic or hegemonic masculinity, which is explored throughout the book. R. W. Connell argues that hegemonic masculinity is dangerous, because it ‘legitimises powerful men’s dominant position in society and justifies the subordination of the common male population and women, and other marginalised ways of being a man’.4 When we consider that it is an ideal that has historically operated in a different way that is fluid and transformative across various cultures, we begin to see how it is not a stable force.

Masculinity is not patriarchy. And while patriarchy is an oppressive structure that imposes the dominance of one gender over another, we must imagine and manifest a masculinity that is not reliant on patriarchy to exist; a masculinity that sees the necessity of the equality of genders for it to not only survive, but to thrive.