Patric McCoy initially resisted labeling himself a photographer — at least in the traditional sense. Coming from a creative family, the Chicago native inherited an artistic sensibility from his father, a painter, a designer, and a photographer, as well as from his grandmother, who documented her travels throughout the 20s. Still, he didn’t want to be the type of person who paid excessive attention to the craft’s technical aspects. Photography’s potential for facilitating new connections fascinated him the most, not so much the possibility of mastering the medium.

“Throughout the 60s and 70s, I carried a little point-and-shoot camera. It wasn’t until the 80s that a friend of mine suggested I get a 35mm camera, because, according to him, I was taking too many good photographs to only be using a point-and-shoot,” Patric tells me. “I didn’t want to learn from my father or from a school, so I made a commitment to myself to carry my camera everywhere I went and take pictures every day.”

Outfitted with his Minolta SLR, he biked daily to his office in the South Loop, where he worked as an environmental scientist at the US Environmental Protection Agency. It was the peak of the 80s, and Chicago was experiencing a kind of structural upheaval that still afflicts residents today. Multiple years of white flight, alongside urban disinvestment and the suburbanization of the surrounding area, left communities of color to deal with decaying infrastructure and increased gang violence. As crack and heroin flooded working-class and impoverished neighborhoods, the Reagan Administration’s ‘war on drugs’ prompted mass incarceration nationwide, further contributing to Chicago’s racial divide.

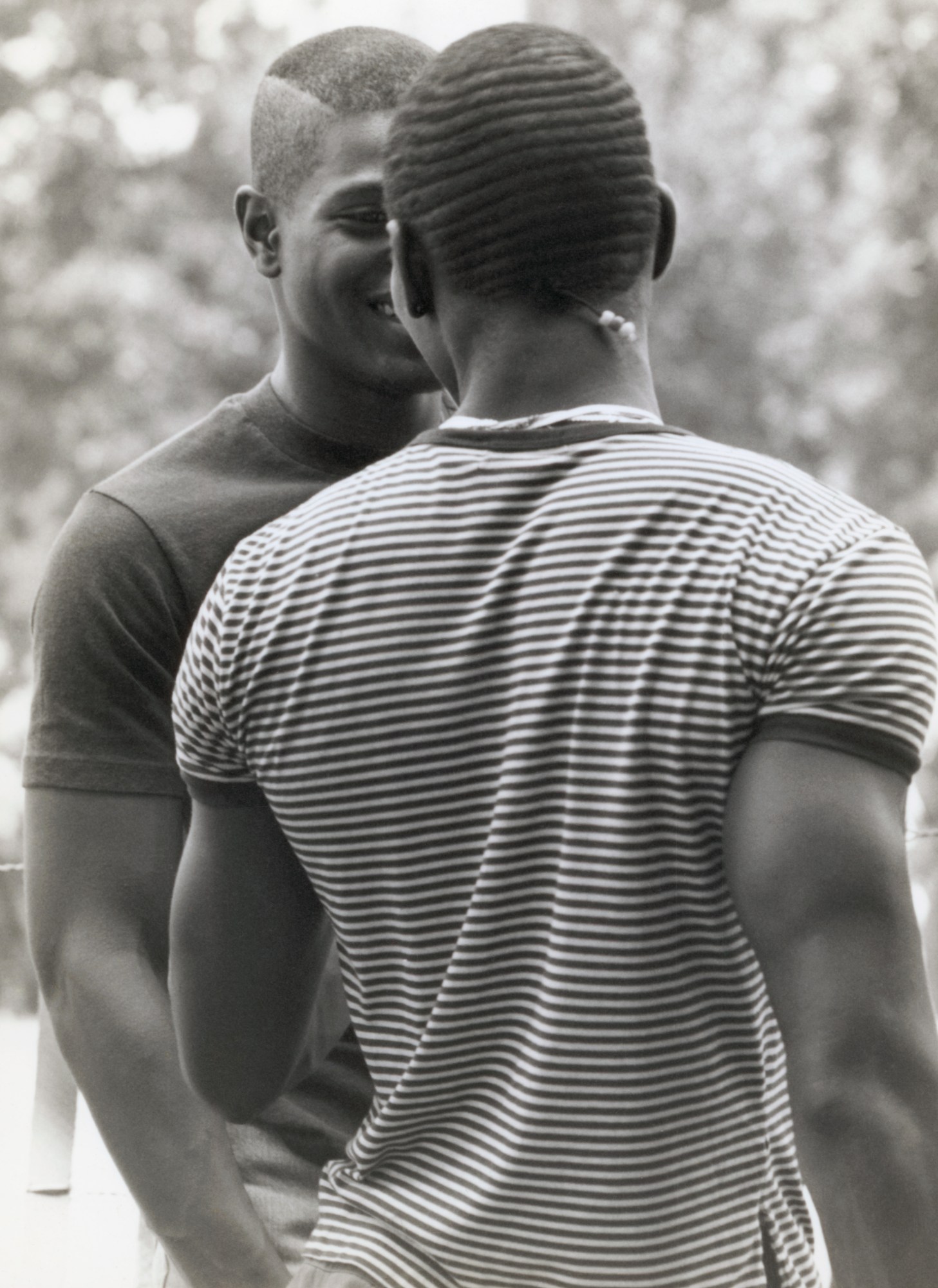

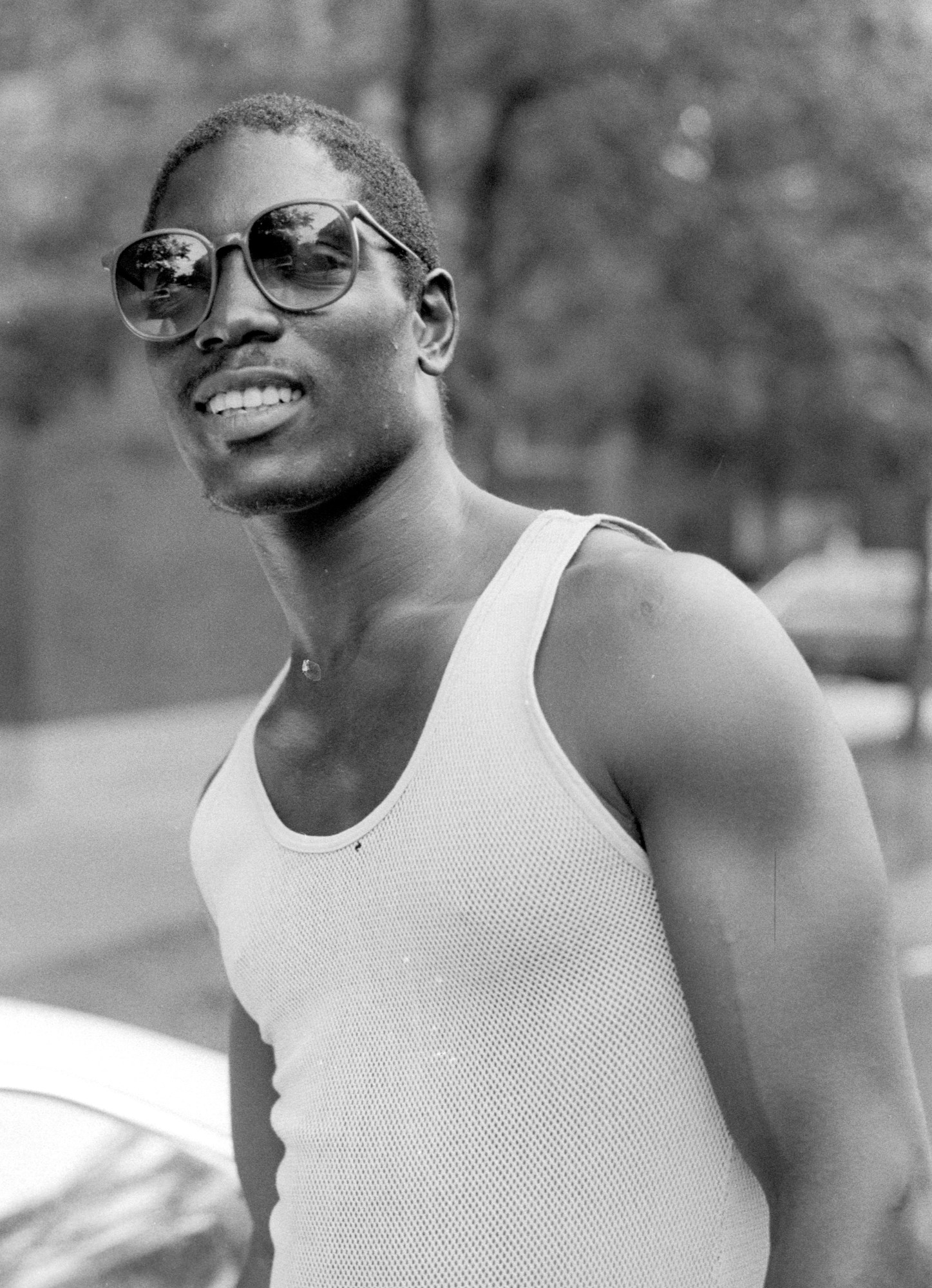

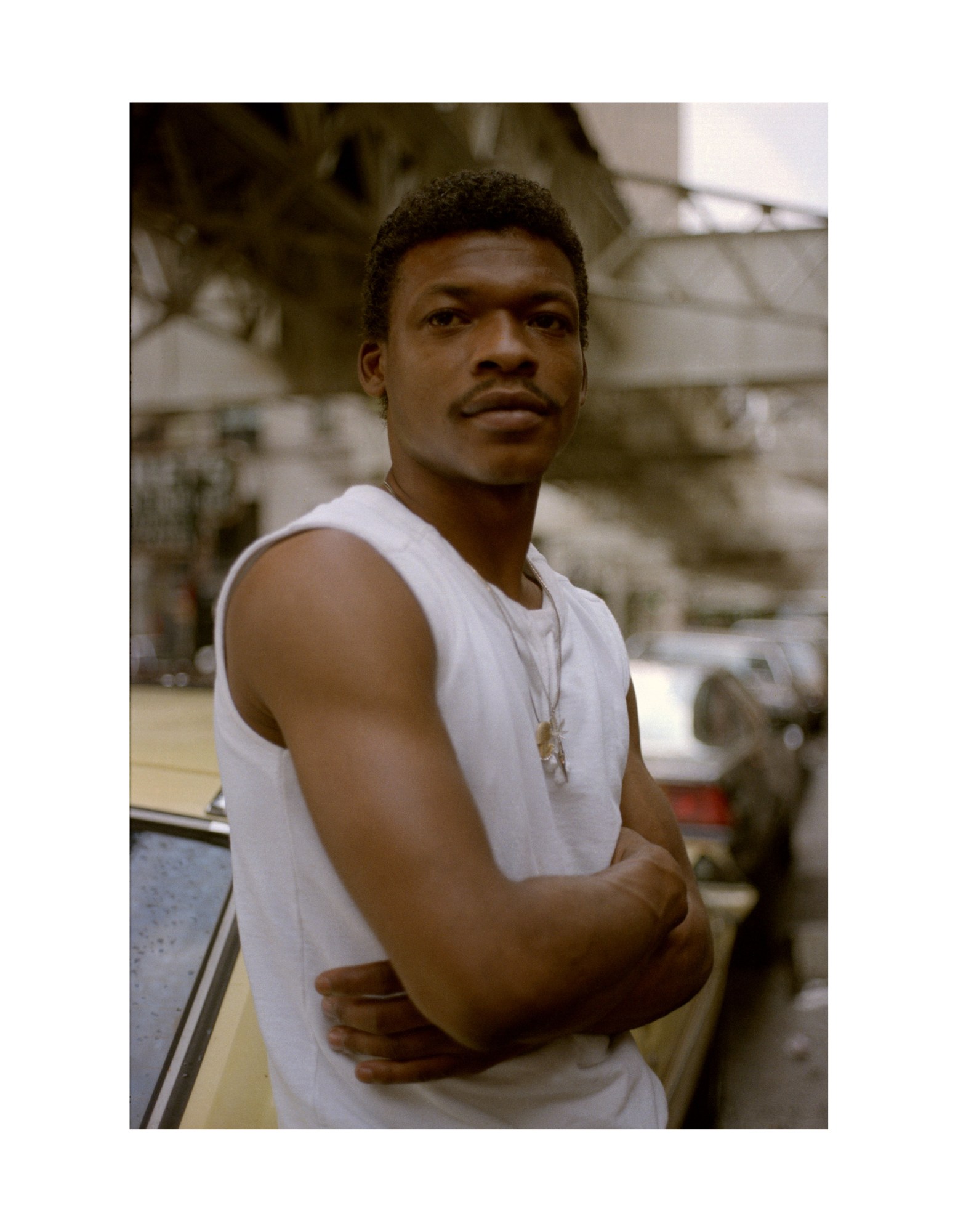

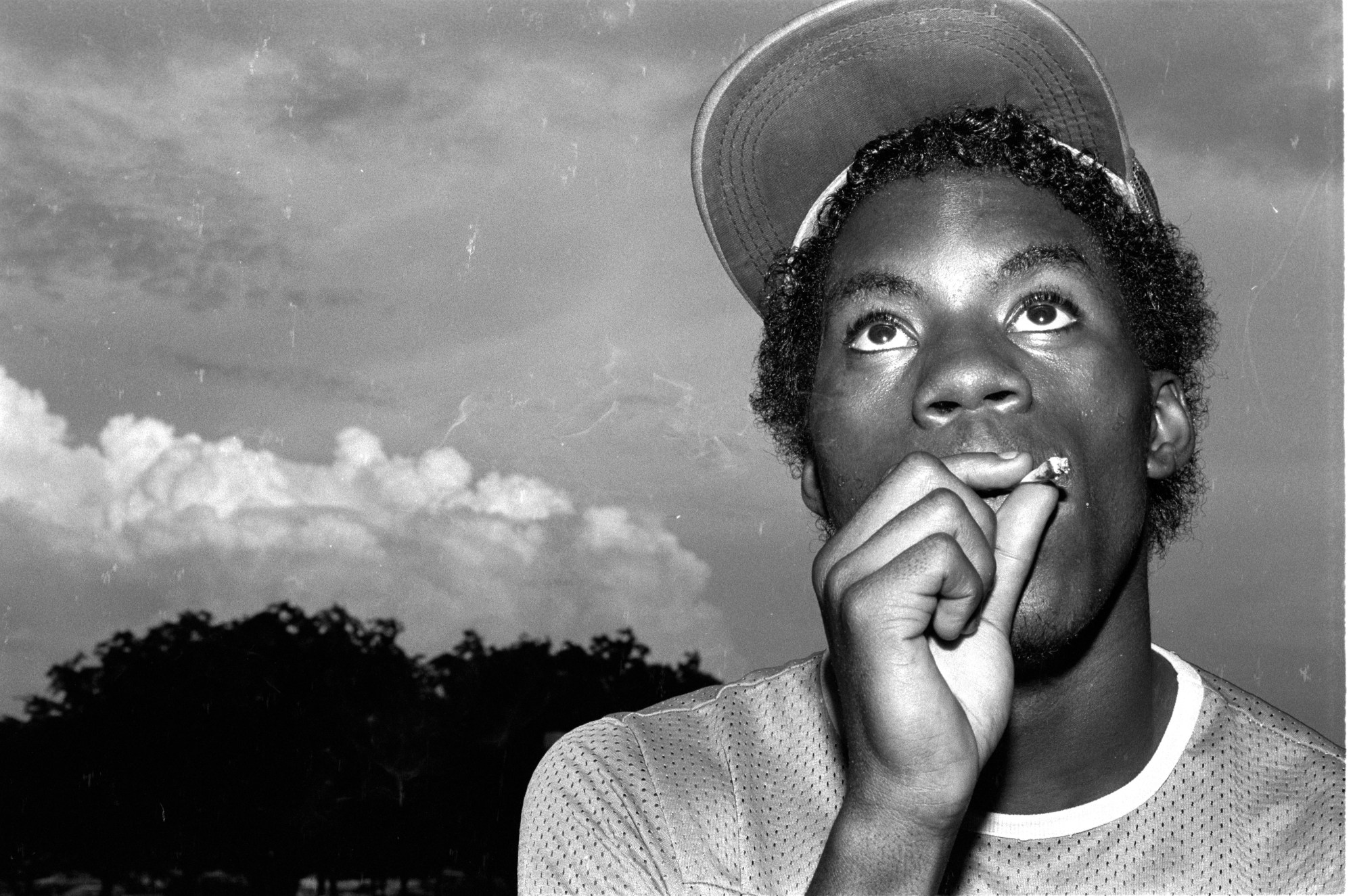

During this era, a lot of Black folks hung out in The Loop – a downtown neighborhood full of restaurants, shops, and bars – which acted as a buffer zone between the North and South Sides. After a while of passing through on his way to and from work, Patric started to take notice of the same familiar faces, including various young men who, spotting his camera, would merely yell “Hey, take my picture!” He obliged, and his hobby eventually evolved into a decade-long project chronicling one of Chicago’s most crucial periods.

Take My Picture, now an exhibition on view at Wrightwood 659, provides a glimpse into this rich archive with a selection of 50 black-and-white and color images, most of which haven’t been displayed before.

“It brings me a lot of joy to look back on these photos, but also a lot of sadness, of course, because of all the people who succumbed to AIDS,” the photographer says, highlighting how the early misconception that the disease only affected white people ultimately had deadly consequences for the Black community. “I also miss the beauty of that time and the way people presented themselves without all of the anxiety and paranoia that exists today within the public domain.”

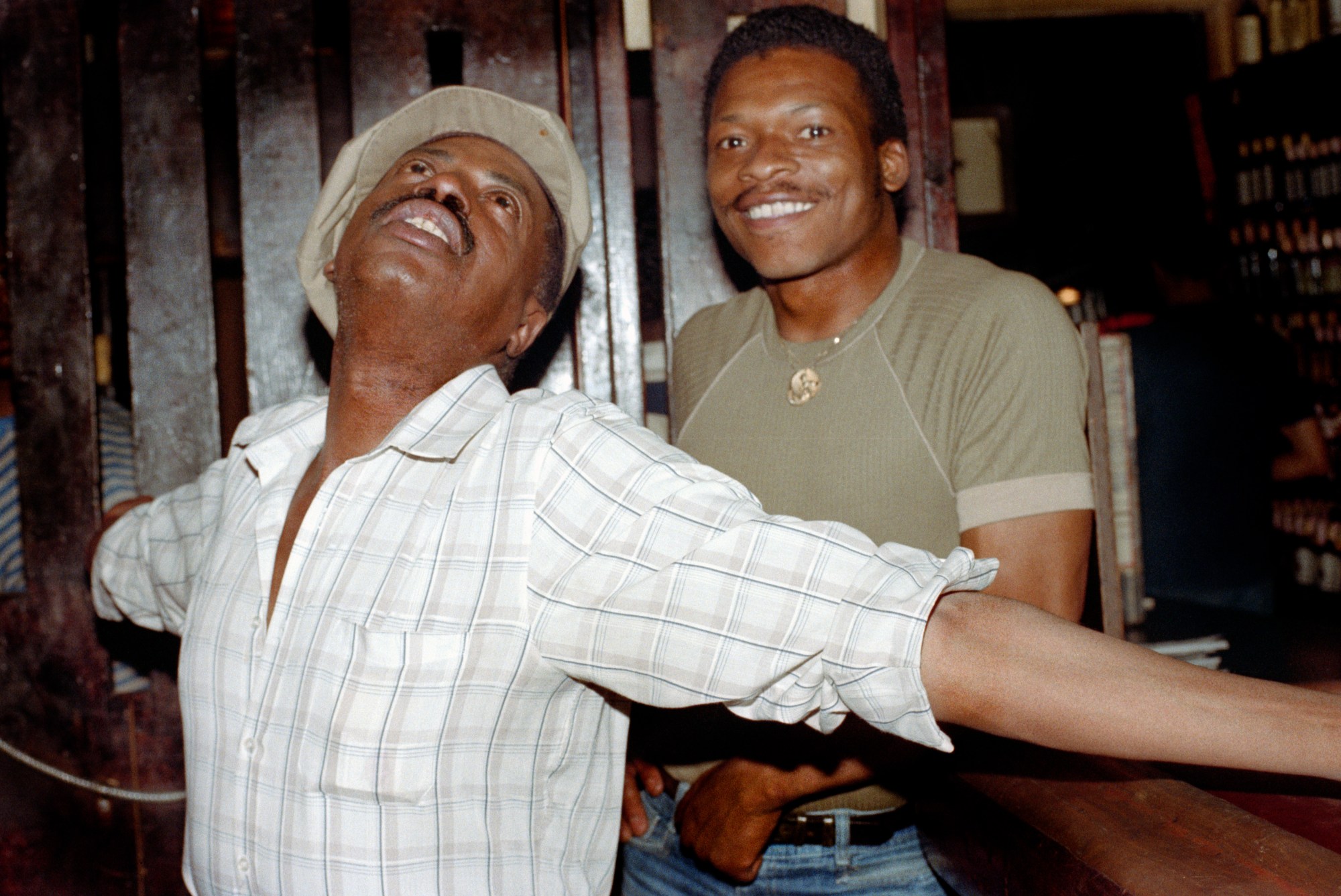

Chicago’s lakefront, city parks, and other outdoor spaces were popular pickup spots, especially in the summer, when buff cyclists donned their skimpiest shorts. Many of Patric’s subjects also frequented the Rialto Tap, a South Loop bar whose clientele consisted primarily of Black men. Though several never defined themselves as gay outright, the establishment served as a gathering place to explore their sexualities and seek out acceptance, something mainstream queer bars routinely denied them. Patric befriended a few of the regulars, and each evening, the Rialto became a backdrop for some of his most iconic photos.

When he returned the next day, carrying a fresh stack of images he developed in his father’s darkroom, everyone jumped at the opportunity to sort through them and point out who they recognized. “Most of those men didn’t expect to see the pictures again, so they loved getting a copy. Once people realized all they had to do was ask for a photograph, they started telling their friends, and it became a way of interacting and developing relationships,” Patric explains. “Every time I came into the bar with new photos, it was a whole ordeal. People would say ‘Oh this is me!’ and ‘I know this person!’ or ‘Who is that?’ and so forth.”

From the city’s unhoused population to local drag queens, the Rialto welcomed all walks of life with the promise of stiff drinks and catchy music. Patric maintained an inclusive practice over the years too, capturing thousands of tender snapshots of friends, lovers, strangers, and anyone else who longed to be seen. One of his favorite images from the exhibit, “Youngbloods”, shows patron Joseph Youngblood with his arms stretched out in celebration, standing beside a grinning bartender also nicknamed Youngblood. It’s a playful picture that perfectly encapsulates how men like Joseph presented to the public – “straight as an arrow,” in Patric’s words – versus how they behaved inside the bar, where they could finally let loose and be themselves, however flamboyant or feminine.

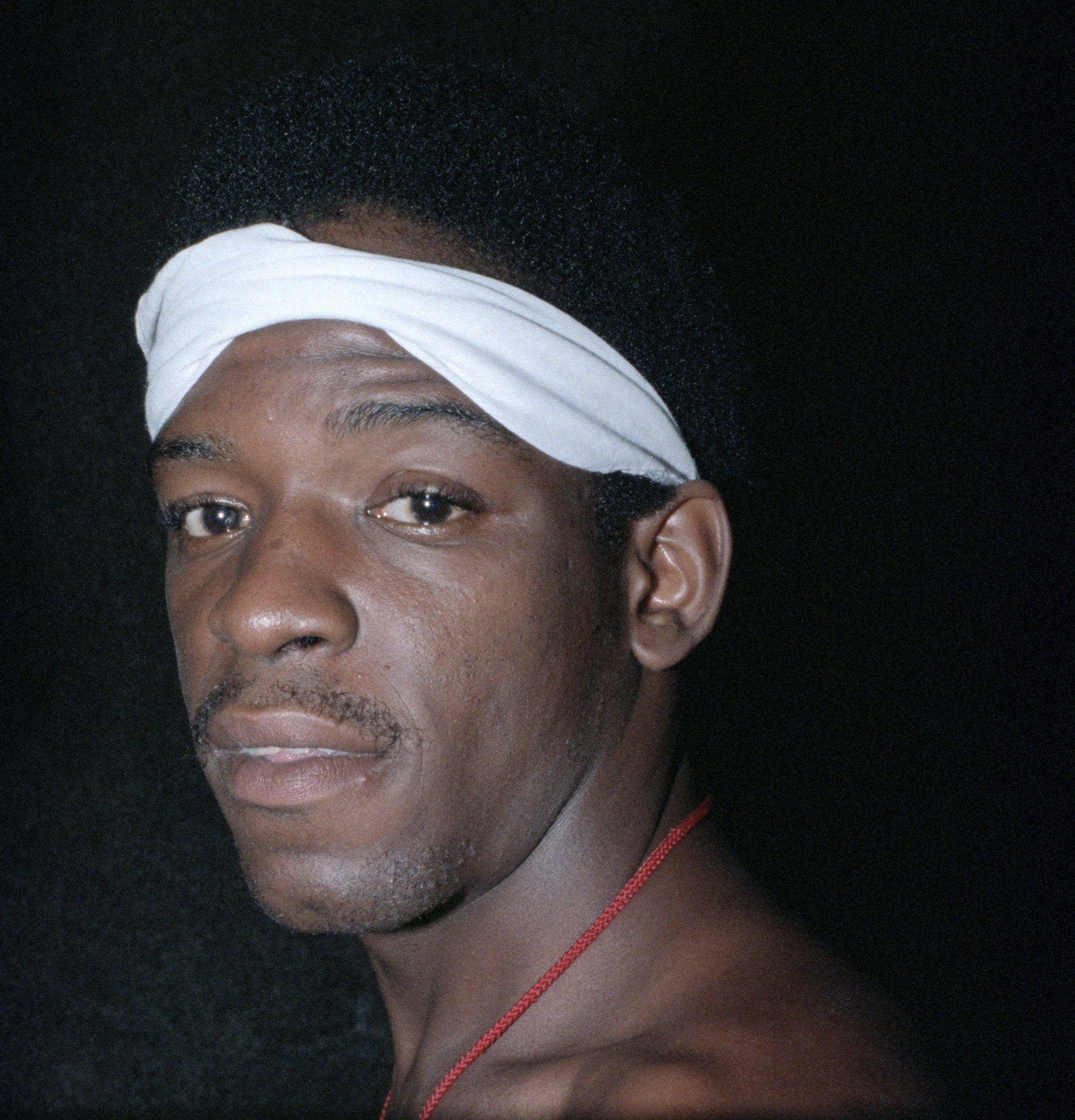

“A lot of people say the subjects in my photos possess a certain look – a ‘come hither’ look of evident desire, yes, but also the look of not being turned into an object,” Patric says. “You almost feel as if you’re being looked at through the pictures. I think that comes from them asking me to take the photographs, rather than me asking them.”

This same sultry stare appears across countless images, conveying what couldn’t be articulated with words. In some cases, the sleepy-eyed gaze was simply a come-on, while other times it seemed to communicate a special chemistry between photographer and subject, neither afraid to perceive one another, and by association, the viewer. Alongside Take My Picture, Patric is also in the process of compiling a new photo book, 38 Special, which will expand on the exhibition and function as a tribute — to the Chicago of his youth, the now-shuttered Rialto, and all the men he met who later disappeared or didn’t make it altogether.

“At first, I felt very brave putting these photos out there, but it doesn’t phase me as much anymore,” Patric says. “I’m lucky that I’ve lived long enough to realize the significance of what I was doing, even if it was after the fact. Now, I truly see the importance of it and understand it was something very impactful – recording these people, their lives, and aspects of what’s referred to today as ‘gay culture.’ I felt totally oblivious to that then. I was only taking pictures and having fun.”

Take My Picture is on view at Wrightwood 659 until July 15th, 2023.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist.