Writer Lizzy Goodman’s New York dream started with a cutout of the skyline on the ceiling of her childhood bedroom in New Mexico. After moving to the city in 1999, she found herself amongst friends who were also figuring out how to navigate their youth in the city and lusting after tales of old New York. They found their guide within the pages of the book Please Kill Me, which documented the mischievous pioneers of the punk scene in the 70s. “There was this sense that there was this bible, this secret text, that would tell you how to do the thing that you’ve come here to do, but that you didn’t know how to name,” Goodman says. “It’s an absolute classic. It was definitely the type of thing where you’d end up being friends with someone because they also had it.”

Goodman went on to release her own uncensored, juicy oral history Meet Me in the Bathroom in 2017. In some ways, it aims to pick up where the former left off and in many ways, it inspires the next generation of young hopefuls — musicians or otherwise — who might need to read it to remind themselves of their shared dream of New York and what brought them here in the first place. Taking its name from one of The Strokes’ songs, the oral history charts the rebirth of rock and roll in the city spanning the years 2001 to 2011. It’s colored with wild tales of “those nights that started as Tuesdays and ended up as Jim Jarmusch movies… followed by Interpol with ten other people at some dank after-hours club.” Now, an exhibit called Meet Me In The Bathroom: The Art Show, which is currently on display at The Hole gallery until September 22, uses multimedia art to expand upon the raucous spirit of the scene she documents so well within the book.

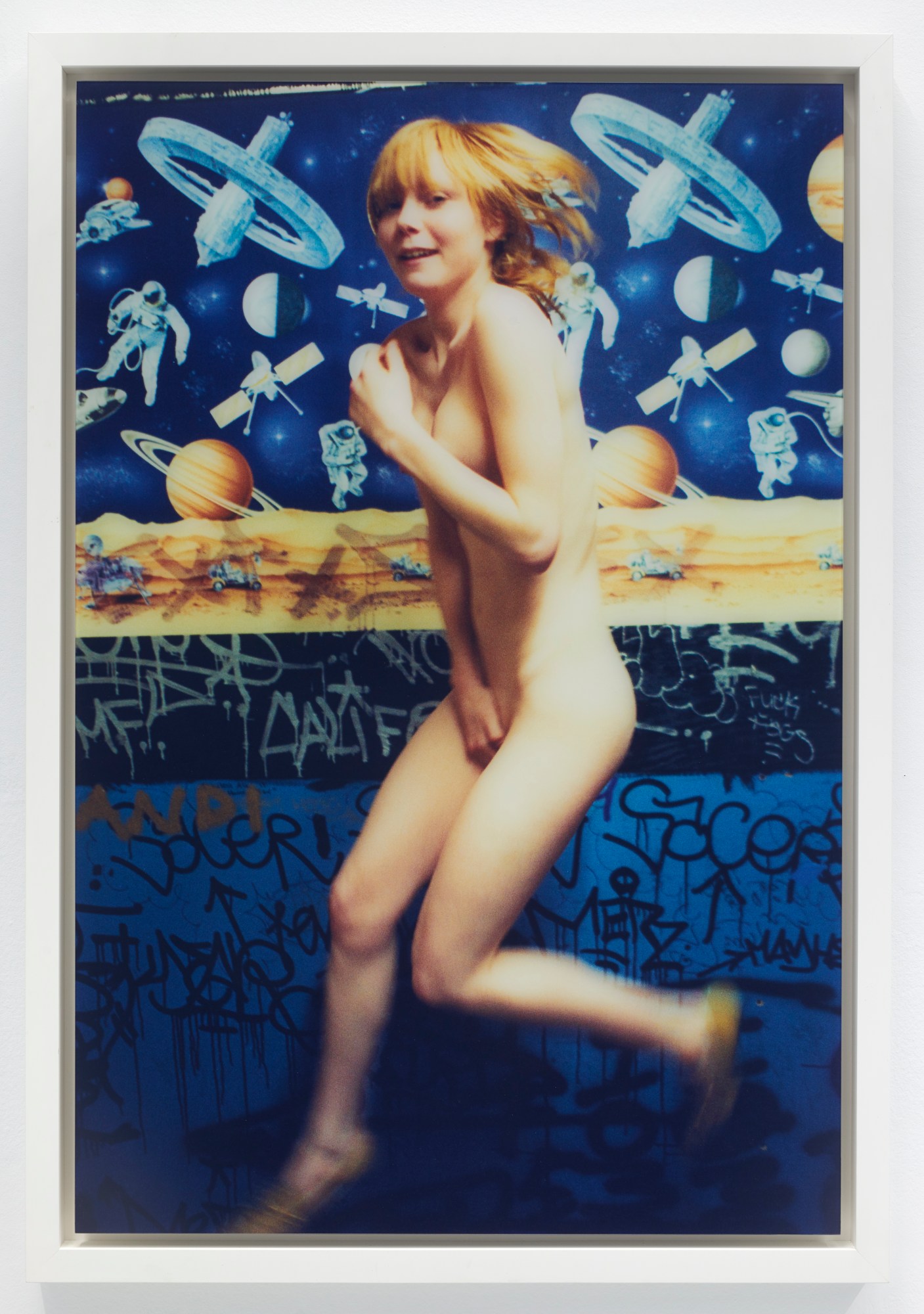

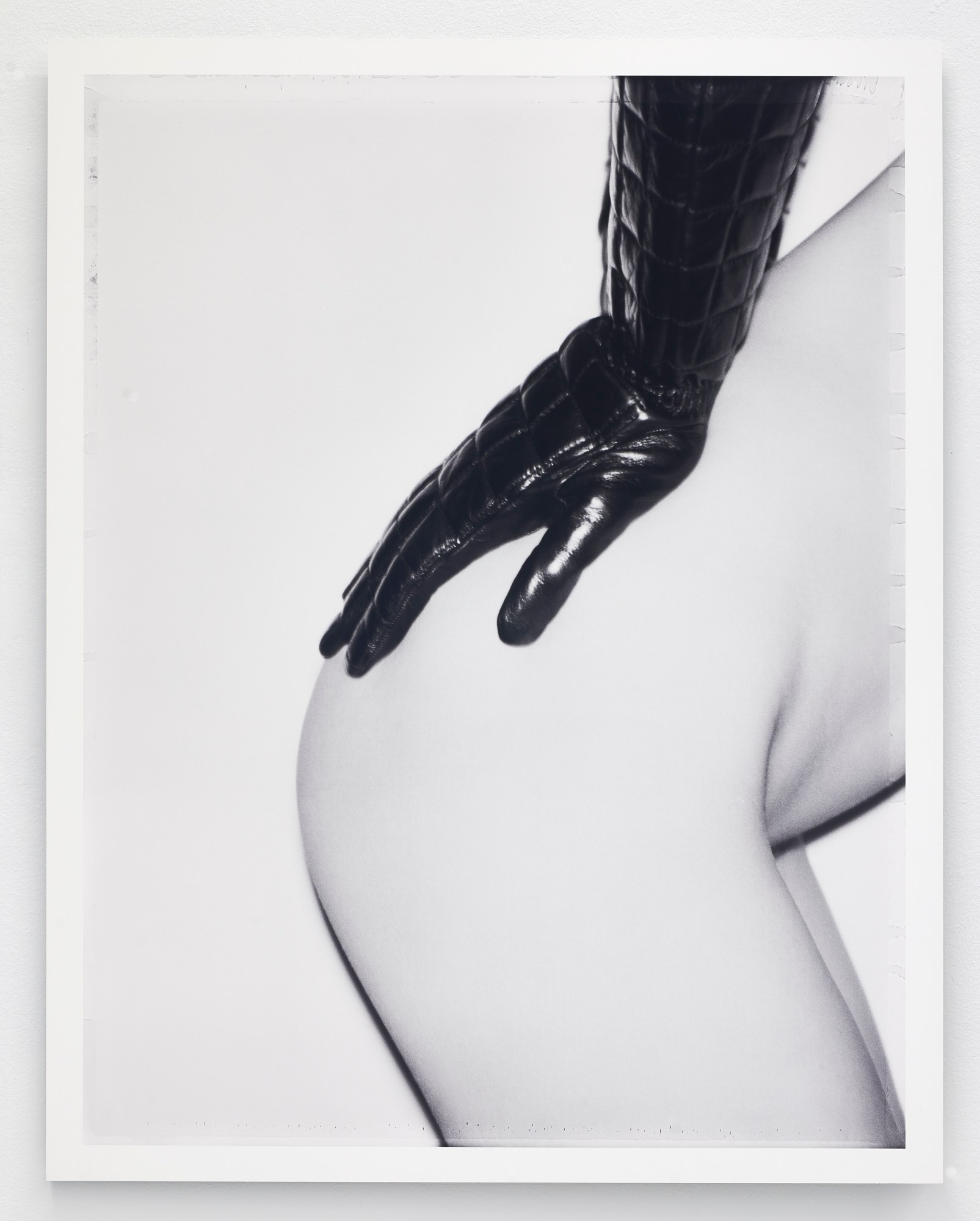

i-D met up with Goodman in the East Village to hear all about co-curating the exhibit with Hala Matar, which brings the spirit of the early aughts to life through photographs and ephemera of New York bands alongside the work of revolutionary artists of the time like Ryan McGinley and Dash Snow.

So, how did Meet Me In The Bathroom: The Art Show come to be?

I met my co-curator Hala Matar at a dinner right after the book came out. She’s a filmmaker and she knows a lot about the art world. She did an Interpol music video that I loved and she was like, ‘You should do an art show.’ And she stuck with it! That was the beginning of the idea, then it was about a year ago that we started trying to figure out if that had legs. We started putting feelers out to the artists and the response was really positive. This is a lot like how the book happened. It’s sort of this slightly hair-brained idea that usually comes a little late at night when things are loose. Not in a destructive way, but in a ‘wouldn’t it be cool if…?’ way.

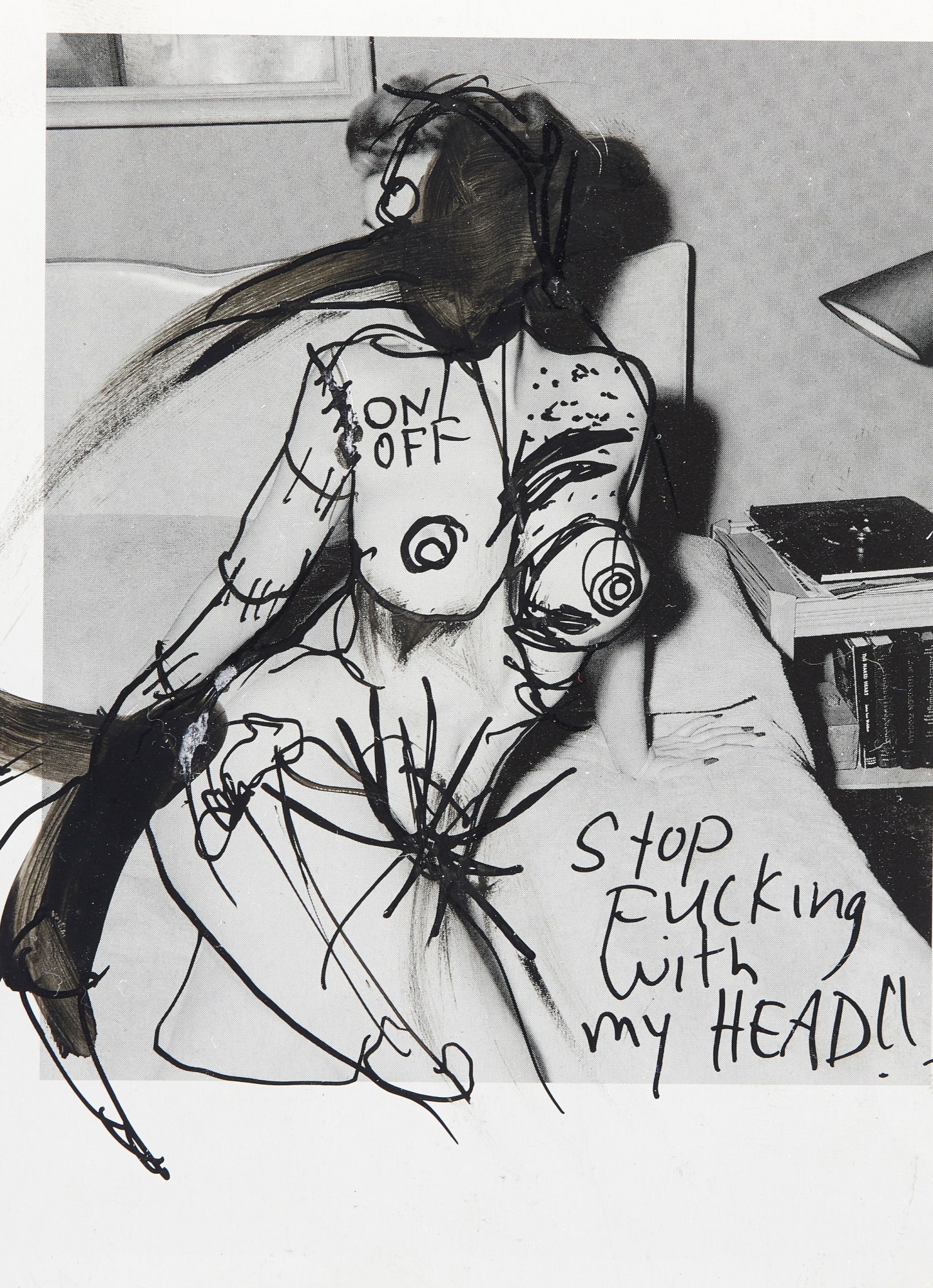

I wrote this entire book with no art direction. There are a lot of great images in the book, and a lot of the artists are also in this show like Ruvan [Wijesooriya] for LCD Soundsystem and Nick [Zinner] for the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. But that’s just the music side. The real theme of the show is a reflection of the spirit of the time in a multimedia format. And that’s not possible in the pages of a book that’s about bands. So, the excitement for me was being able to give space to all of this artwork that I knew about, but I did not have the resources to access and all of this artwork that I didn’t know about. There are these concentric circles of life in New York, where on any given night there are a thousand stories going on, whatever bar you’re in. But if you just took a snapshot of that moment and then pulled out each individual – what they did that morning, what they did that night, who they’re texting, who’s hurt them recently, who they’re lusting after, you get this web of lives that are interwoven. That’s what makes the city magical. Dash Snow, Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen… we were part of each other’s concentric circles.

Who were some of the first people that you thought to reach out to for artwork?

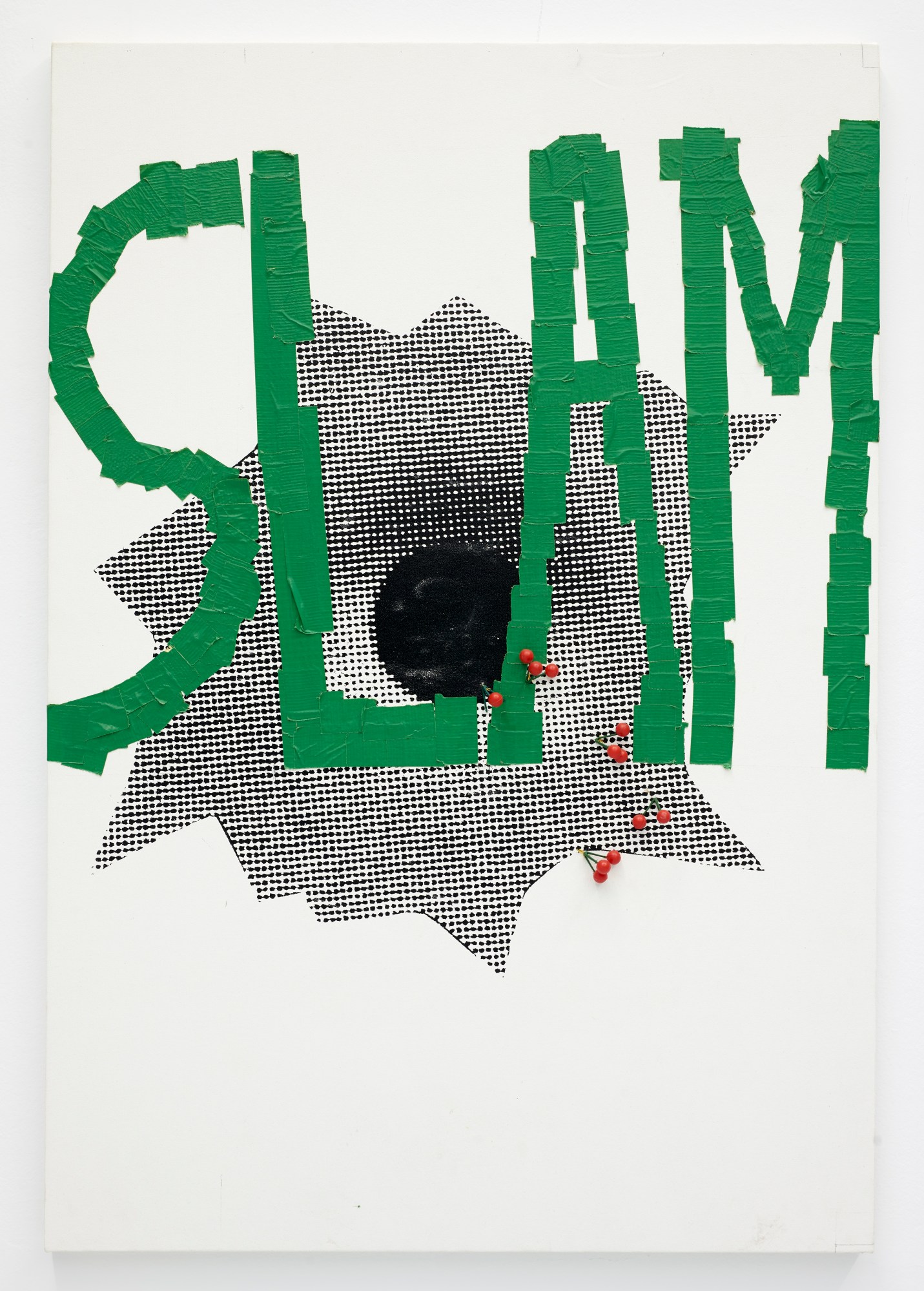

Karen O and Christian Joy. Her collaboration with Karen just feels so unique, strange, powerful, and representative of this sense of ‘youth and abandon’ I always talk about. The joy and fragility of this era that Meet Me In The Bathroom documents is specific to our particular time because of all the cultural forces that were at play. It’s a post 9/11 scene, it’s a post technological revolution moment, there’s a war going on… The coming of age story is happening in a way it always is in New York, but it’s also a new century. Yet, the Karen and Christian union is so electric and alive. They would pull each other’s pants down and come home from partying covered in bruises from wrestling with each other. Obviously with Karen’s stage persona, there is a lot of aggression there, but that blend of glee, joy, and dark femininity with violence is just amazing and really inspiring. There’s one costume in the show called the ‘What’s Eating Karen O Dress.’ When Christian first made it, [Karen] cried when she put it on because it was so ugly. But that was the point, the idea that revulsion is beautiful. In an era where everything’s so pretty and so slick, I just miss that. That’s what I wanted to capture.

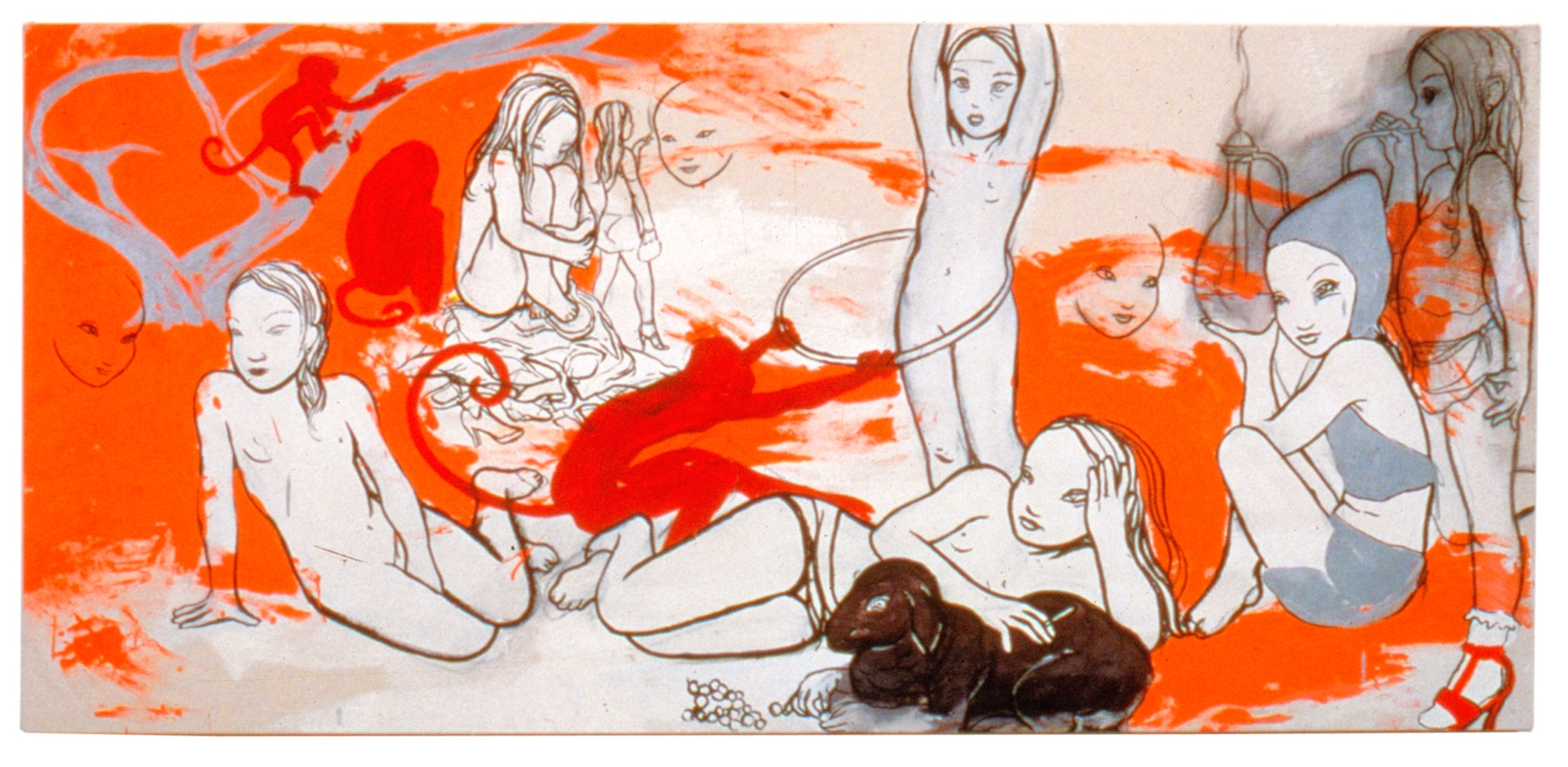

The Rita Ackermann piece reminds me of the story of New York that was slightly ahead of me that I lusted after when I moved here. The sort of languid, deconstructed youth. Like you’re just going to move here, wander around doing absolutely nothing, and just look amazing doing it. And find other people who look amazing and then sort of destroy each other, and that’s what you came here to do. There’s a weird sweetness to that in retrospect because it’s like our culture has gotten so dark that it doesn’t sustain pockets of that anymore. It’s not revolutionary to go and get destructive with your friends in a corner because in a way that doesn’t show any contrast to the world you’re growing up in. The idea of doing drugs or living a sort of counterculture life required a fairly stable culture to be escaping from.

Right. Rebelling against a stable atmosphere, whereas now it’s entirely corroded. Ryan McGinley, Dash Snow, and that whole art scene seems equally if not more debaucherous. In what ways does their work play into the show?

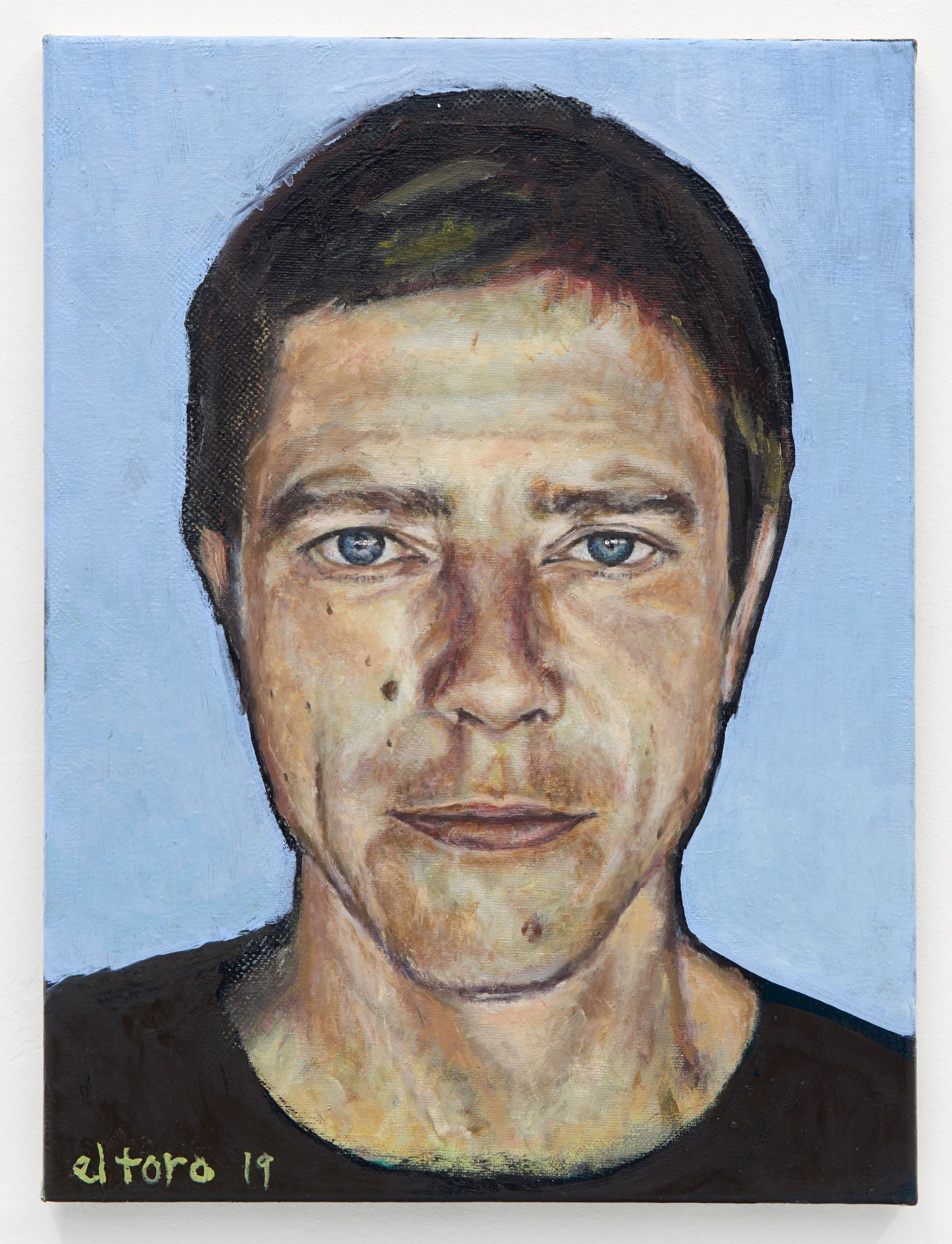

Obviously Ryan McGinley’s amazing. The Dan Colen, Nate Lowman, Dash Snow thread, seeing that come to life in all of these works that are on the walls is really cool. In retrospect, there really was something in the water here at that moment. How does a geographic place and the people that are there happen to become a thing that changes culture? What is the special sauce mix that creates that reality? And if people knew the answer to that, they’d be able to script it and they don’t. There are some ingredients that you need. You need relatively cheap rent. You need not a lot of eyes on the place seeking the thing because otherwise there’s too much pressure. New York is always a demanding place for bands, but at the time this all happened nobody thought bands were cool and it’d be the last place that you’d be looking for a rock band. That creates a sense of defiance and freedom. What I recognized in those artists is that they’re doing the same thing and it feels like they’re pulling on the same thread. The end result — a painting, a series of photographs, a sculpture — is their personal reflection and story about the same feeling that I heard coming off of Nick Valensi’s guitar in 2001.

I had this post it on my bulletin board when I was writing. My ex Marc [Spitz] told me ‘Never stray too far from the bar.’ Don’t let it get too far from kids in bars making trouble because that is the story. There are a lot of high concepts and notions like generational identity and how 9/11 affected the creative world, but you can’t go at it that way. The version of that here is that we held every artwork up against a certain similar standard. How does this piece make me feel? This is about trying to create a portal to the events during this time. It should feel a little unstable or unsafe. I want people to walk into the gallery and not be sure that they want to stay, but be compelled anyway.

The book creates this sense of nostalgia for this time you might not have experienced, but maybe you’re aware of or at least aware of the music. How does the exhibit work to imbue this sense of nostalgia?

I think it’s important that it’s not a museum show. There’s something about generating the energy of this particular time that is contemporary. We’re trying to understand ourselves now and you can understand the origin of so much of the culture we’re currently living in by understanding this particular sliver of past. Like, why are we like this now? Why are our hands holding computers all day long and why can’t we stop Instagramming about ourselves? How did we get here? When did I lose the ability to sit still for five minutes and be in my own head? Or, if you’re really young, what would that even be like? In looking at this era, and bringing the feeling of that time to visceral life it’s aimed at putting the present into new context.

What are some of the other events that bookend this era and this scene, allowing it to exist in the way that it does?

It’s not easy doing interviews for an oral history because it’s not as linear. There wasn’t a lot of stuff that I asked everybody but one thing was, what was your myth of New York? What did New York mean to you before you got here? Then I asked everybody what was the first album or song they downloaded and where they were for 9/11. The second two were these huge tectonic shifts during this era that shape the entire culture. Meet Me In The Bathroom provides a window into why you’re hearing what you’re hearing on the radio, or why downloading culture has shifted the story of music, and the sense of young people’s relationship with their own notions of rebellion, rock stardom, and youth, in comparison to what we used to recognize as the standard paradigm of how you get to be young in America. That changed overnight. And this is the last time it happened that way, ever.

Stewart Lupton, who was the singer of Jonathan Fire*Eater, calls it “nostalgia for an hour ago.” That’s how it felt. You felt nostalgic for the thing that you’re doing and the moment, which I think is a fairly obvious forecasting of how we all live now with Instagram stories and the fact that we’re constantly documenting ourselves. This idea of war or violence and it being in your backyard is really unnerving and it changes your emotional DNA. It also inspires you because you’re like, ‘I’m going to die. I should make everything that I’ve ever dreamed of making and I shouldn’t be afraid of whether it’s going to look stupid or sound bad, whether the guy you have a crush on is not going to think it’s cool.’ All of that is there and it’s all about to change. The idea of New York and what it means to people is eternal. It’s a place you go to become bigger than wherever you were from. It’s a permission slip to the kind of life that you want to have. That piece tells the story of this book and it tells the story of this show. It’s an idea that’s evergreen and incapable of dying, being lived out at a moment of unprecedented technological and political and social change. But basically, it’s about drinking.

Drinking and being afraid of dying.

Kind of, yeah. And trying to get laid. (laughs).

The exhibition is curated by Lizzy Goodman and Hala Matar, organized by The Hole and UTA Artist Space, and presented by Vans. Signed, limited edition prints are available here via Absolut Art.