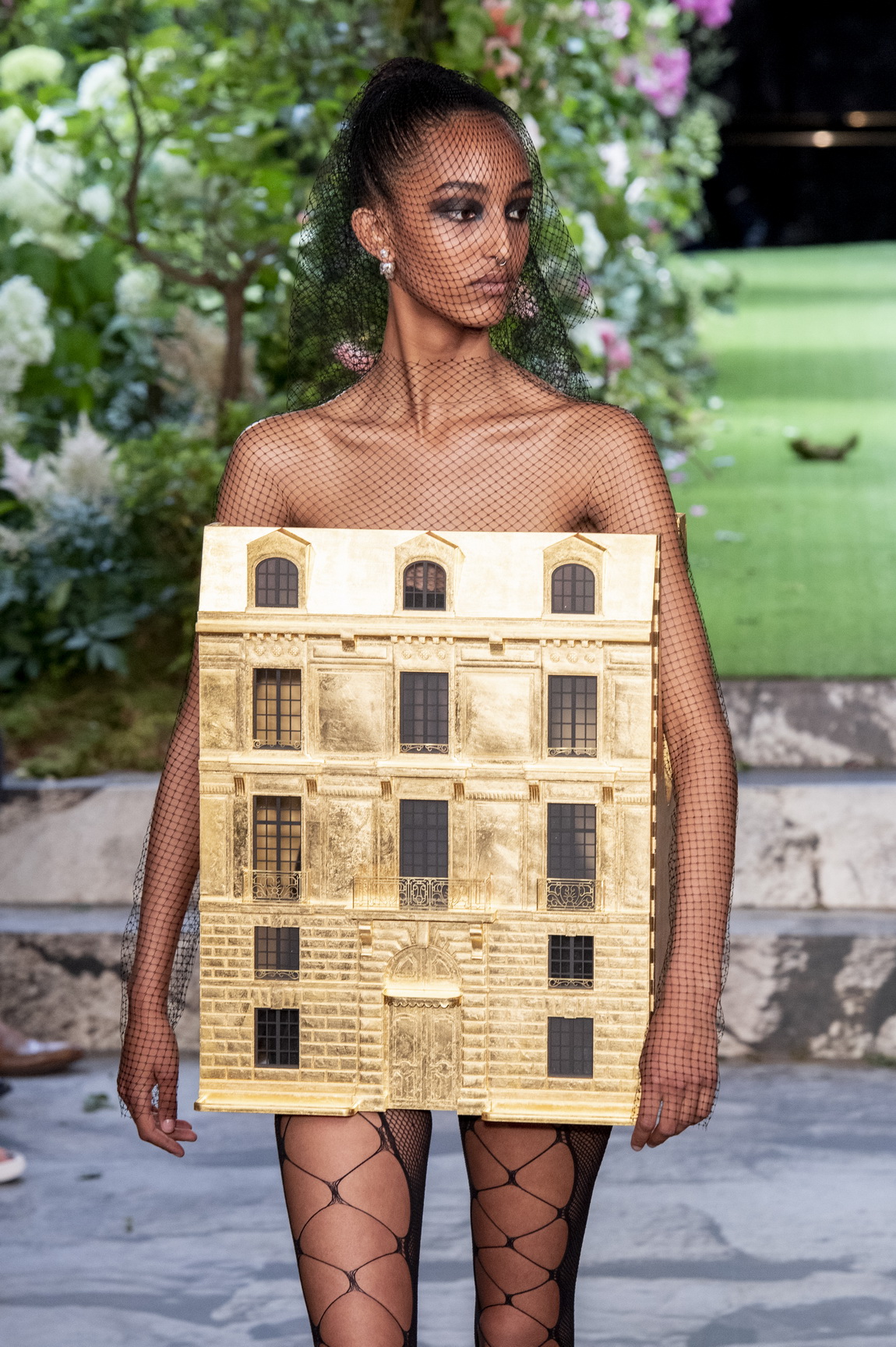

A house is a home. Though when it’s a couture house, it’s usually a household name too; a maison with heritage and history. Millions of us might carry a bit of it around with us, whether it’s a perfume, lipstick or a handbag. The very few that are lucky enough to be haute couture clients may even consider the hand-crafted garments as homes for their bodies — at least that was the thinking behind Maria Grazia Chiuri’s latest couture show for Dior, which was held at the house’s home at 30 Avenue Montaigne. “Couture is a space where you can design the house for your body the way you want — with the help of the designer, the team and the ateliers,” Maria Grazia said before the show. She also meant it quite literally. To close the show, she sent out a model wearing a golden doll’s house of Dior HQ. It ignited the internet, spurring thousands of memes, almost immediately.

This season, Chiuri was getting philosophical about the role of clothes in our lives. She stumbled across Austrian-American polymath Bernard Rudofsky’s seminal 1944 book Are Clothes Modern? A book that questioned and criticised fashion’s function and potential harm to health. He deemed corsetry, stilettos and restrictive skirts — the hallmarks of his contemporary, Christian Dior — as harmful, functionless and dangerous. Instead, he favoured the Ancient Greeks’ peplos (a draped, shapeless tunic) and comfortable sandals — if he was alive today, he’s probably be wearing T-shirts and Birkenstocks. Monsieur Dior, on the other hand, interpreted the toga in 1957 with an internal boned corset and posed drapery. Function versus form, nature versus artifice, reality versus fantasy… You get the point.

Maria Grazia set out to combine both and prove Rudofsky wrong. “I wanted to explain we can do any shape or any construction with effortlessness,” she explained. I don’t want this idea that you are nonfunctional or functional, minimal or decorated. You can find a balance in the contradictions.” Her gowns for Dior came with “comfortable corsets” — made of fabric, rather than boning — and there were plenty of grounded Grecian sandals. To reiterate the point, she sent out two versions of the peplos. One was elegantly free-flowing with a drawstring waist. The other sinuously form-fitting.

The approach resonated with Chiuri’s broader mediations on the purpose of haute couture. As she mentioned, she sees it as a second home for her clients. In her eyes, it’s all about them; couture is the ultimate individual experience. Hence why she made the collection almost entirely in black — it was designed to be a blank canvas for her clients, namely because Dior can make the dresses for them in any colour or fabric that they choose. “The customer needs to be more conscious of what they want for themselves,” she explained. “In the past, the creative director defined the house and the clients came. Now couture is an experience where the clients come to build a one-of-a-kind experience. You can decide the shape. You can decide the material.”

It’s a reflection of Chiuri’s mission as an outspoken feminist, just as it is her welcoming legendary feminist artists into the Dior fold. This time it was Penny Slinger, the British-born surrealist who is the subject of an upcoming documentary and a current exhibition in London. Penny Slinger created a fantastical set for the show, evoking nature’s transformation throughout the seasons and spiritual sculptures of female body. She also came up with the idea of that golden 30 Avenue Montaigne dress, a surreal take and witty take on the couture bride.

“Maria Grazia has this programme of working with strong women artists and collaborating and bringing that work through into fashion, so she is making the bridges between these two worlds,” the California-based artist reflected before the show. “She’s really out there on the front line, bringing it to an area that we haven’t really seen this kind of thing manifest before. This is the frontier we have to charge across.”

Interestingly, Christian Dior was criticised for arguably setting the women’s lib movement back a decade following WWII. He re-introduced corsets, longer skirt lengths and high-maintenance glamour. Feminists protested against it at the time, carrying placards emblazoned with “Burn Mr Dior”. As we see a revival of those arguably Victorian values in the age of social media — Kim Kardashian in a corset at the Met Gala, Kylie Jenner in impractically long acrylic nails, Elle Fanning fainting in a too-tight gown at Cannes — it’s an poignant moment to consider the dichotomy between modern women’s lives and fashion’s ideas about femininity.

What did Slinger, the 72-year-old feminist make of the modern corsets? “What I like is that Maria Grazia is using the aesthetic of that look and the way you can transform silhouettes, but doing in a way that is soft and free-flowing, using soft fabrics and moulding with the materials themselves rather than constricting the bodies of women,” she said. “We do want to use our bodies as art forms but we also don’t want to lose a rib or two in the process. We want beauty and style without harm.”