“Every answer to every question I have starts with a photograph,” Liz Johnson Artur begins, speaking over the phone from her home in south London. “For me a photograph is a way to tell a story.”

It’s a few days before the opening of her new exhibition, If you know the beginning the end is no trouble, at the South London Gallery. The exhibition is big — more than 100 photographs easily — but compiles just a segment of the work the photographer has created since she moved to the UK in 1991. What it does is provide an incredibly moving, hopeful, and poignant overview of the photographer’s work. It is a document of the people, spaces, communities of the black diaspora across the world.

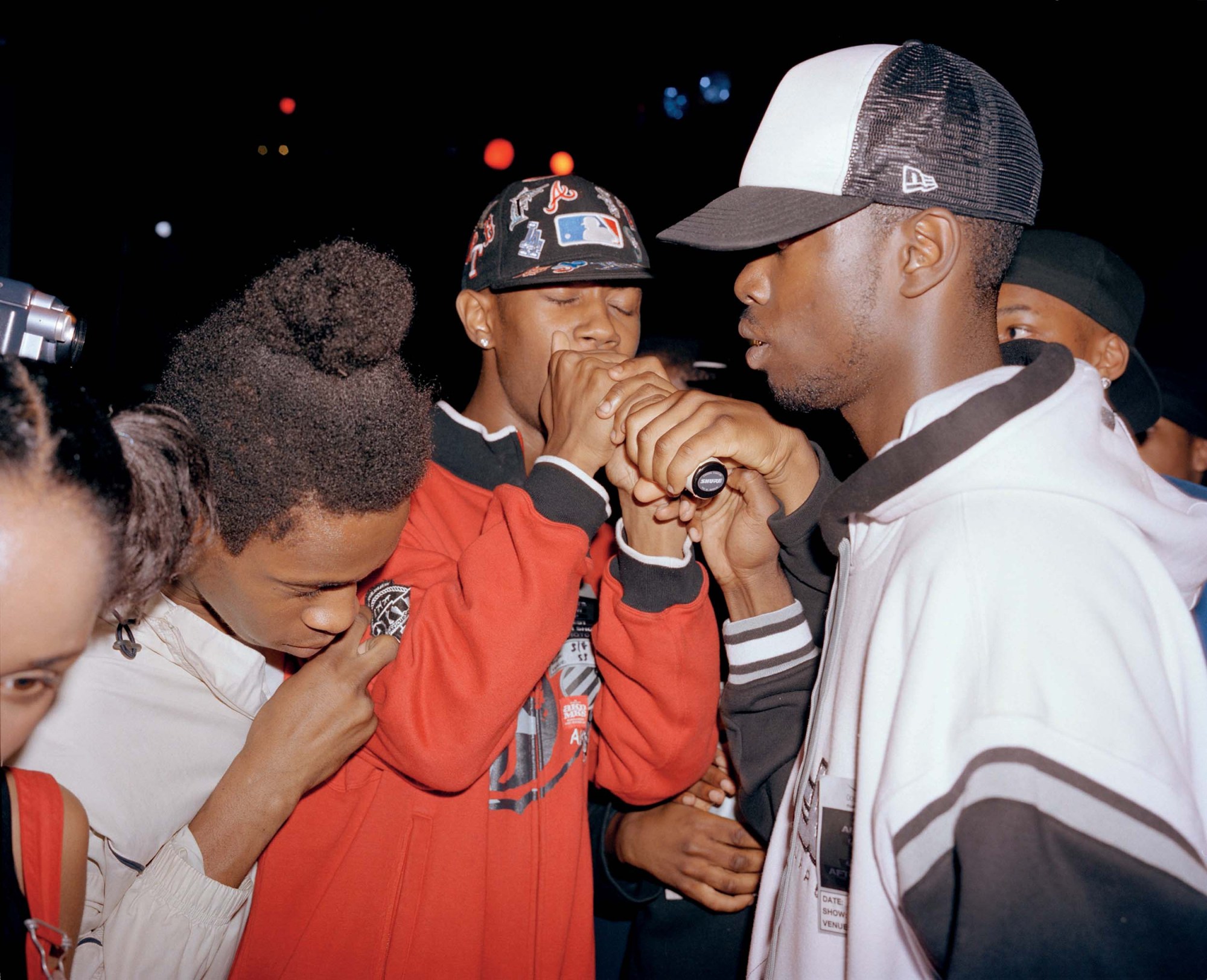

Born in Bulgaria to a Ghanian father and a Russian mother, Liz had an uprooted, international childhood, moving first to Germany, then spending some time in New York, before settling in London where she picked up a camera and started to shoot the world around her. This photography developed into what she calls The Black Balloon Archive, an ever-expanding collection of images full of noise and joy and energy, quiet beauty and community. She captures grime raves, church goers, community gatherings, police searching a young man in park. It features ordinary people, ordinary scenes, ordinary events. A day in the life of London.

The images are arranged thematically, hung across bamboo structures Liz has installed in the gallery. The structures will, over the life of the exhibition, form a backdrop for a series of talks, events, gigs and gatherings. Liz is opening up her show to the community, selflessly giving over space to everyone from experimental musician Nkisi to internet fashion star Miss Jason and PDA’s Ms Carrie Stacks.

In fact one section of the exhibition, the most recently created work, is devoted to iconic clubnight PDA, features glammed up and stripped back images of the club night’s cast of creatives and characters. It’s the last bit of the exhibition you get to as you navigate the space, in the furthest corner, but seen within Liz’s wider archive, this body of work seems to link together all the various stories that her images tell. It looks into the present and towards the future, seems to suggest a continuum of black experience and creativity that can’t be stopped, won’t be put down. There’s a thread that connects all of her photographs together. The exhibition is not simply an archival study looking back, but a constantly updating feed that seems to take in everything.

It’s really exciting to see you with this exhibition at the South London Gallery. It’s a kind of homecoming, showing in the place you’ve lived and worked in for most of your life.

I’ve been based here since pretty much the beginning of my career, so in a symbolic way it feels really important. It’s influenced the vibe of the pictures I’m showing and it’s made me think about the people I’ve photographed. Perhaps people that know them will come and see the work. The way I shoot… well a lot of people I’ve photographed never see the pictures.

I love the title of exhibition — If you know the beginning the end is no trouble — it kind of sums up your work really well. The sense of narrative to it, this suspended feeling.

As a photographer, what I do is quite traditional. The interesting stuff happens after the photograph is taken. The narrative really comes out when I show the images. With the exhibition I’m trying to replicate how I display the photographs in my studio.

Are you talking about these bamboo screens you’re making?

Yeah. I wanted the exhibition to be more than just pictures on the wall. This show gives me a great chance to give space to artists I’ve met over the years and that I think deserve to be in the same space. So the exhibition is like a set — a place to invite others into, give them space to do their thing. It’s an opportunity to give my work some function, rather than simply being something to look at. I wanted to create something in London that felt very London, being on home turf and all that.

I love those new images you shot at PDA. It really places that club night in a lineage within this larger body of your work. It felt really exciting to see.

I think we could sum up what I do as creating a space for a community and I’m trying to use the tools I have to represent this community. There’s no real definition to this community; it’s the people I photograph, the people I meet. The moment happens and I try to catch it. That’s what happened with PDA, I met them about a year ago. I found them so refreshing, it’s a generational thing, a London thing, but they have this energy. I’ve been in London since 1991 and the generation PDA are part of have it much harder than I did when I came here.

The spaces where places like PDA can exist in this city are shrinking.

Not just shrinking but disappearing. It’s really difficult to do anything. One of the things that made photography possible for me was my studio. I got it in 1994 and it was a possibility then for people with no money to get a space. It’s so vital. I couldn’t have done what I’ve done without that. It’s so hard for the younger generation to get space. But youth can’t be stopped. Creativity can’t be stopped.

There’s something hopeful there too.

I’ve always seen my work as positive. I’m not pointing fingers. I’m not trying to teach people. I want to show people what’s there. If you care to look, you will see so much.

Do you think of what you do as political? You document spaces and communities that aren’t given the respect and attention and cultural importance they deserve.

In the 90s I worked as a freelance photographer, mainly for i-D and The Face, those magazines were the only places I could get my work published. The galleries weren’t interested. Forget it! But times are changing. And whether its political? Well it’s a question not worth answering. Tell me something that isn’t political?

Was having the Brooklyn Museum show and this show at the same time a coincidence? Or somehow related?

It was very much a coincidence! Both shows came towards me. I never considered either.

Did you approach both in the same way?

Well it all starts in the archive.

With such a big archive though… How do you even start?

Well that’s a question, that’s a question… I don’t even know how to answer! I shoot on film, I’ve always tried to keep an eye on my negatives, but it is not necessarily a very organisational eye. I can find my things, but I’m still trying to find some kind of order. I’ve been doing this for myself and by myself, and there’s a personal order there. It’s part of how I work. I like to spend time just going through boxes of what I have, pulling out things I’ve not seen for years. That process becomes incorporated into how I show things.

Is there a lot in there you’d forgotten shooting?

I had my studio in Peckham for 25 years and then after Grenfell we had to move out of the tower block because it was unsafe. We unpacked so many boxes, boxes I hadn’t seen in fifteen years. You discover things, but I see an image and I know where and when it was shot. I can remember it all. I like putting things away, though. I go out, take some pictures and put them away for ten years. That’s how I work. It’s luxurious to have that freedom, no pressure.

You had to move out of Peckham though?

They’re going to renovate all these blocks. But of course they’ll do something, get a different demographic in. It is a process most Londoners experience one way or another, especially if you don’t own your house.

Do you still get excited by opening a new exhibition? Or nervous? Or do you still care about the public’s reaction to the work?

I’ve been a photographer for a long time but the process of showing the work is actually quite new. I’ve had these two shows this year, but it’s a new period of my career and actually showing work means letting go of something that has been private for so long. For me, that process has been very interesting artistically, solving that problem of how to let go. The process of doing this exhibition, it’s like getting something out of my system.

Does the same thing still inspire you to create an image today as it did when you started?

I love people and I love to take pictures, and the whole process is something I’m dedicated to. I explore the things I want to explore by taking a picture. I’m a creature of habit; I’ve spent my career trying to become a good photographer because that’s the only way to make what I want to do worthwhile. And I’ve been doing it for so long now that I feel like I know what I’m doing as a photographer. It’s about instinct: the moments are so short and I’ve trained myself to take the pictures that I need. You learn to sense what a moment can give and what a moment can be. It’s about feeling and instinct. I’m not someone who plans, I like to find things.

Liz Johnson Artur’s exhibition ‘If you know the beginning, the end is no trouble’, is open at South London Gallery until 1 September.