Every two years, the Whitney Biennial promises a wave of new artistic voices to define the pulses of contemporary American art. Now, two years into the Trump presidency and with fears and anxieties about the racism and corruption that drives the administration largely replaced by anger and resignation, the air that dominated the 2019 survey was one of inevitability.

Demographically, this year’s roster is far more balanced than it ever has been before. Of the 75 participants, half are women and more than half are people of color. Almost three quarters of the artists are under the age of 40 and only five have ever been featured in the Biennial before. The show’s two female curators, Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, are themselves 35 and 46, respectively.

“In part, this emphasis resulted from what we saw during our research across the U.S.,” Panetta said in a statement. In the year leading up to the Biennial, Panetta and Hockley traveled extensively across America, of course to Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, but also to non-coastal points in between like New Orleans, Detroit, and Puerto Rico. “We were struck by the profound difficulties of our current moment and the ways in which so many artists we encountered are struggling and facing fewer opportunities to present their work publicly,” Panetta said.

The Whitney Biennial, which promises a “frontline report on what’s happening in American art today,” for the second time in a row has been instrumental in sparking important, difficult, and uncomfortable conversations about the art world’s political mandate. The last edition of the Whitney Biennial was marked by protests prompted by the white artist Dana Schutz’s depiction of Emmet Till, a black teenage who was lynched in 1955. This year, the backdrop of the show is the ongoing controversy surrounding Whitney board trustee Warren B. Kanders, the CEO of Safariland, a company that sells tear gas that was recently used on migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border. Many have publicly called for Kanders to resign, including 95 Whitney staff members and almost 50 of the 75 participating artists. The artist Michael Rakowitz pulled his piece from the show.

Surprisingly, the only flagrant indictment of Kanders and Safariland at the Biennial is Forensic Architecture collective’s video, “Triple Chaser.” Co-directed by filmmaker Laura Poitras and narrated by musician David Byrne, the 11-minute collaborative project uses machine learning technology to track the instances in which Safariland tear gas was deployed against civilians, including the murder of 154 Palestinians in Gaza. These six months of ongoing protests questioning museums’ relationships with toxic philanthropy echo the 1969 protests by Guerilla Art Action Group demanding the Rockefeller family resign from MoMA’s Board of Trustees for its involvement in the manufacture of weapons. Fifty years later we’re nowhere closer to demanding that money be held under a microscope, but hopefully the display of pieces like this is a step toward museums not only welcoming criticism, but holding themselves to higher standards.

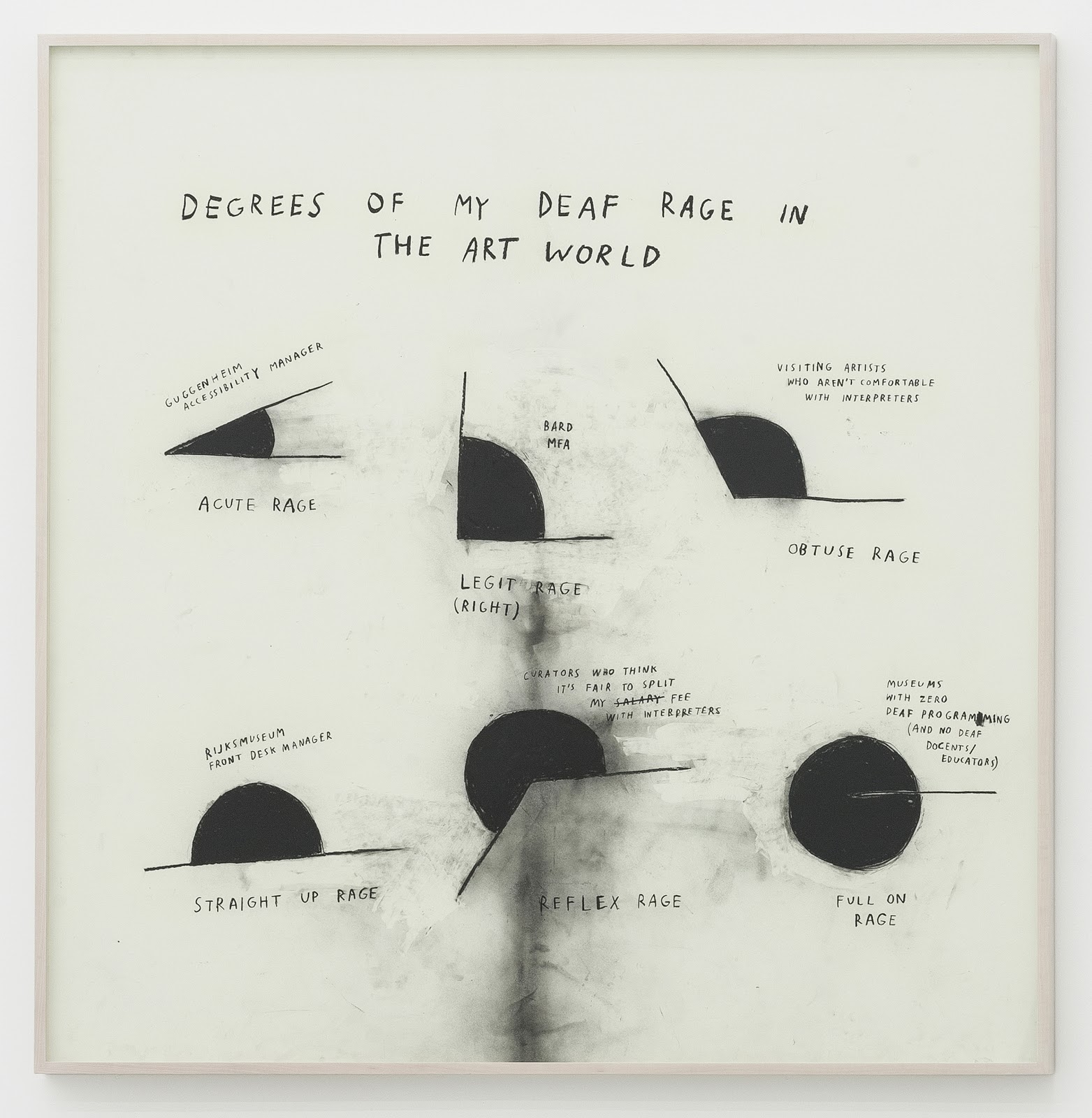

Another kind of indictment comes in the form of Christine Sun Kim’s heartbreaking “Degrees of My Deaf Rage in The Art World.” In six little graphs, the artist manages to record the degrees of her fury at the art world’s largely overlooked failure to accommodate people with disabilities, from “obtuse rage” at visiting artists who aren’t comfortable with interpreters to “full on rage” at museums with zero deaf programming, including a lack of deaf docents and educators.

The rest of the works quietly and with some tired resignation address the fact that this is the first Whitney Biennial assembled entirely while Trump has been in office. Somewhat apathetically, artists consider how racism, nationalism, and privilege have gone into feeding both ends of the spectrum of our current system of wealth accumulation, from Eddie Arroyo’s small paintings of a shop in the Little Haiti neighborhood of Miami being erased by gentrification, to “The Maid,” a silent film by Carissa Rodríguez showing the homes of ultra-rich collectors who own editions of the Sherrie Levine copies of Constantin Brancusi’s “Newborn” sculpture. Ilana Harris-Babou’s three-part video, “Human Design,” probes the insidious hidden connections between forced migration and material culture through a humorous riff on the objects for sale at the high-end design store, Restoration Hardware and the Native American artist Nicholas Galanin’s beautiful depiction of a static-filled TV screen in “White Noise, American Prayer Rug” powerfully asserts that “whiteness as a construct has been used historically throughout the world to obliterate the voices and rights of generations of people and cultures regardless of complexion.”

Galanin’s piece blends especially well with the curators’ overall aim for the show to function as a rejection of the digital and “the slick, packaged presentation of the self.” Indeed, the body of idiosyncratic works at this year’s Biennial resist a tendency towards grand narratives, and maybe that’s what best reflects the fragmented visions of America we are all grappling with. The piece that best sums this up is Nicole Eisenman’s huge outdoor sculpture, “Procession.” A troupe of ten misfits made from materials like sweatpants, raw wool, and butcher’s wax occupy the Whitney’s sixth floor terrace, one has a severed head, another one appears to be farting. They have nothing in common except that they are all moving forward—maybe towards the end of the American Empire in all that it has come to mean and towards a future where museum heads can no longer be apathetic towards their political responsibilities. They are slow and downtrodden, but, hey, they are headed somewhere.

The Whitney Biennial continues through September 22 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.