Many people see rave as a British phenomenon, but the 1990s also saw an explosion of free parties and electronic music in Poland. Unleashed by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the USSR, the parties also served as a space for those seeking solace in communal gatherings, unsure of how to operate in a newly privatised world.

With the fall of Communism came access to the synths and computers that had already fuelled the rise of electronic music across western Europe. This led to the emergence of techno in Poland, the musical heartbeat of its rave scene.

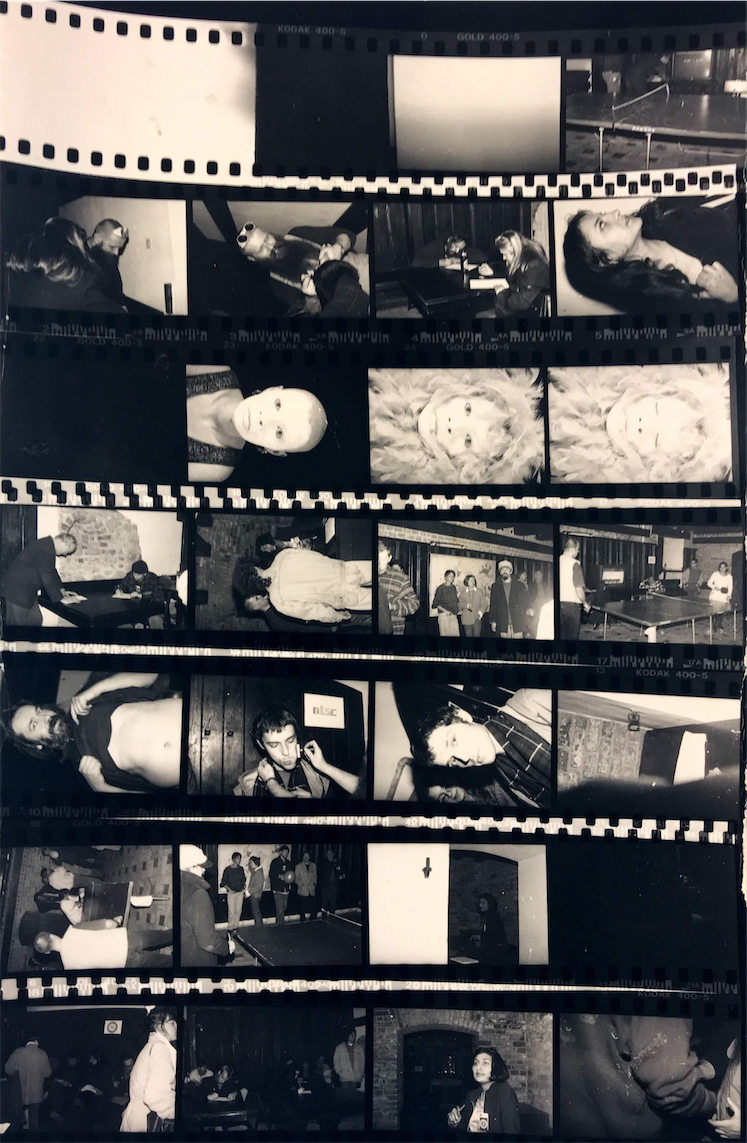

A new exhibition, 140 Beats Per Minute. Rave Culture and Art in 1990s Poland, takes place in London this week at the Tate Modern, celebrating that unique era. Using film (found footage and amateur recordings from raves, combined with old TV broadcasts abut clubbing), art and music, it documents this Polish subculture.

Among the dozen 8mm and VHS films — black and white, colour, some silent — giving life to this world, are works from experimental (often multi-disciplinary) artists like Paulus Mazur — a painter, illustrator, poet and prose writer — and prominent contemporary artist, Wilhelm Sasnal. There are also screenings of films by collective CUKT — Technical Culture Central Office — a group exploring politics, public space and the transmission of public information through billboards, posters, and the internet.

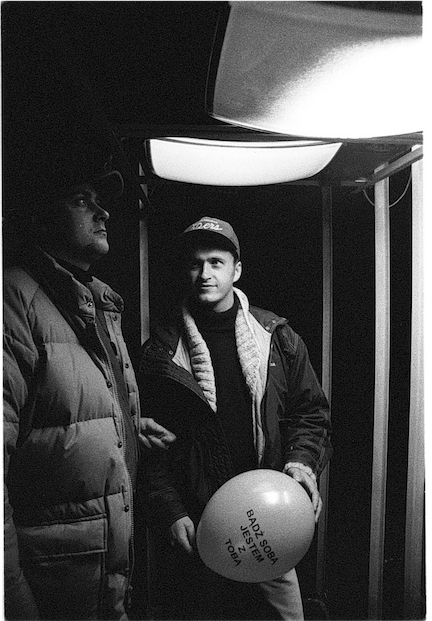

Describing the feeling of raves in 90s Gdańsk, video and performance artist Piotr Wyrzykowski says that they had “A feeling of unity. Being together in a safe environment with no physical violence. Raves at that time were a kind of hub for establishing new creative connections, coming with new ideas about how to realise them.”

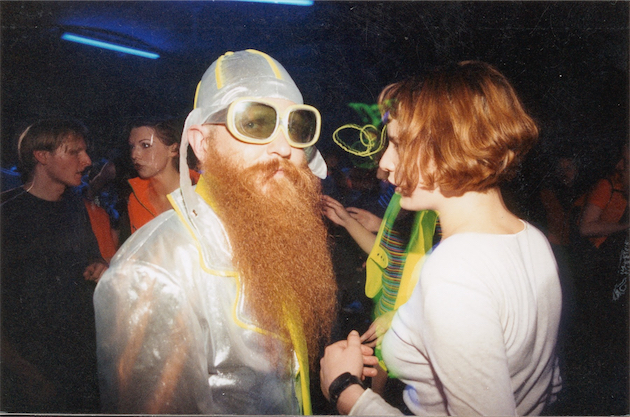

Artist and frequent collaborator of Piotr Wyrzykowski, Anna Nizio says raves were another way of exploring ideas around what Poland could be. “It was a moment when a new subculture was booming and it gave us a new way to communicate with mass audience in public space — outside of the art gallery space — with audio-visual messages,” she explains. “The bigger the party, the bigger the impact of the message. It was a time of fresh hope in Poland. From grey 80s punk we entered an era of raves full of colour. I don’t remember the music at all. Trans people, new drugs, daydreaming and more and more colourful people gathering together. Chickens painted with fluorescent paint running through the whole club under UV lights…”

It’s not surprising that Nizio remembers the experience as something more than simply music. In Gdańsk, everything was political. “It a very specific place to grow up,” explains Wyrzykowski. “A city where World War II, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the death of Communism was won on the streets. Techno for us was a tool to develop revolutionary ideas.”

This revolutionary, artistic approach to rave could be seen all over the country, in major cities but also — like the UK free parties that traced their way along the M25, turning the countryside into a party paradise — cropping up in smaller towns, not just major cities. Nizio and Wyrzykowski recall a 10-day rave installation in 1994 in Konin, a town in central Poland, called 120 hours of Mega Techno Presents Art Is A Cult Space Or There Is No Art At All, which was a kind of social experiment in the basement of a former Communist shopping mall.

That same year they worked on a party dedicated to freeing a DJ imprisoned for marijuana possession. It was held in Krzysztofory Gallery in the middle of the old town of Krakow, with works of iconic Polish artist Kantor on the brick, arched walls alongside political projections. Wyrzykowski remembers: “We Invited local DJs to play and I did a live video mix with two VHS players, a projector covering up all gothic arches and free acid being given out.”

Of course music was a central part of Polish 90s rave too — not just art and revolutionary ideas — as Wyrzykowski says: “Techno was a medium and the message. By organising different conceptual based raves we were transferring our information to the mass public.”

The end of Soviet control in the country meant fewer restrictions in terms of where you could go at night (and what you could play or dance to while you were there), what records you could listen to, what equipment you could buy and what other countries you could travel to. “It was all basic setup. The easiest way to create electronic music was to experiment on computers on so-called ‘trackers’,” remembers Jacek Sienkiewicz, a DJ who started playing at raves in 1993.

He says the changes in the country made making music, and experimenting with sound, easier. “It all changed when I bought my first sampler in the mid 90s. I think samplers made production more accessible and quick. That was a milestone, it became my main instrument for next couple of years.”

Thanks to the new freedom to import music, DJs could now buy records abroad, which meant they were exposed to new genres like trance, hip-hop, jungle and breakbeat. “It was more like a mix of all new trends in music instead of just techno or rave,” Sienkiewicz says. “I remember my first parties in Warsaw — we had all kinds of ‘new’ music: industrial, breakbeat, trance, hardcore. That was the beginning of all underground subcultures.”

Like artists Nizio and Wyrzykowski, his abiding memories of the parties were a sense of liberated euphoria. “It was total freedom and fun,” the DJ reminisces. “Ultraviolet and strobe lights… we never had any problems with the police and we were young and stupid. A good old acid time.” Sienkiewicz now makes electronic, ambient, experimental records on his Warsaw-based label, Recognition. But—– as can be heard on new Aphex-esque record IMOW — the early discoveries he made in 90s Poland still figure in his work.

For Łukasz Ronduda — one of 140 Beats Per Minute’s curators — the early 90s was important because of the meeting of music and art via rave culture. “The intersection of the rave scene and visual art… these two spheres were very friendly to each other,” he explains. “There were strong ties between the music scene and visual arts and dance… there was a lot of experimentation going on at this intersection.

“Artists saw the rave scene as a breeding ground for a new kind of community, as opposed to the communist community that was fading away. It caused anxiety but it also inspired awe and fascination. They were questioning the futuristic cybernetic dimension of rave.”

What made 90s rave in Poland so unique though, so very different to its UK counterpart, was a joy in claiming national identity. UK party-goers were rebelling against the Thatcher-led powers-that-be, while in Poland they rejoiced in new freedoms and at the idea of shaping a new country.

“We were lucky enough to create a feeling in Gdansk of living in the centre of the present time,” Piotr Wyrzykowski says. “Not thinking about emigration to Berlin. A sense of ‘If you are here, you know what you are here for’. This was a time when the Western borders opened for Poles and leaving was one of the options available to us. But we decided to stay. ‘We are at home or we are not here at all.’”

Find out more about the 140 BEATS PER MINUTE – RAVE CULTURE AND ART IN 1990s POLAND exhibition, which took place as part of KINOTEKA Polish Film Festival here .