On 6 May 2018, India’s supreme court voted unanimously to overturn a colonial-era law that criminalised homosexual sex. For a country of 1.3 billion, it’s an unprecedented milestone in LGBT+ equality, sparking celebration among India’s campaigners and its global allies. With this institutional change so begins a long road towards a wider cultural shift and a future far safer from persecution for the country’s LGBT+ population. Though, perhaps the metaphor of a singular road doesn’t work for a change that takes in this many unique experiences and perspectives.

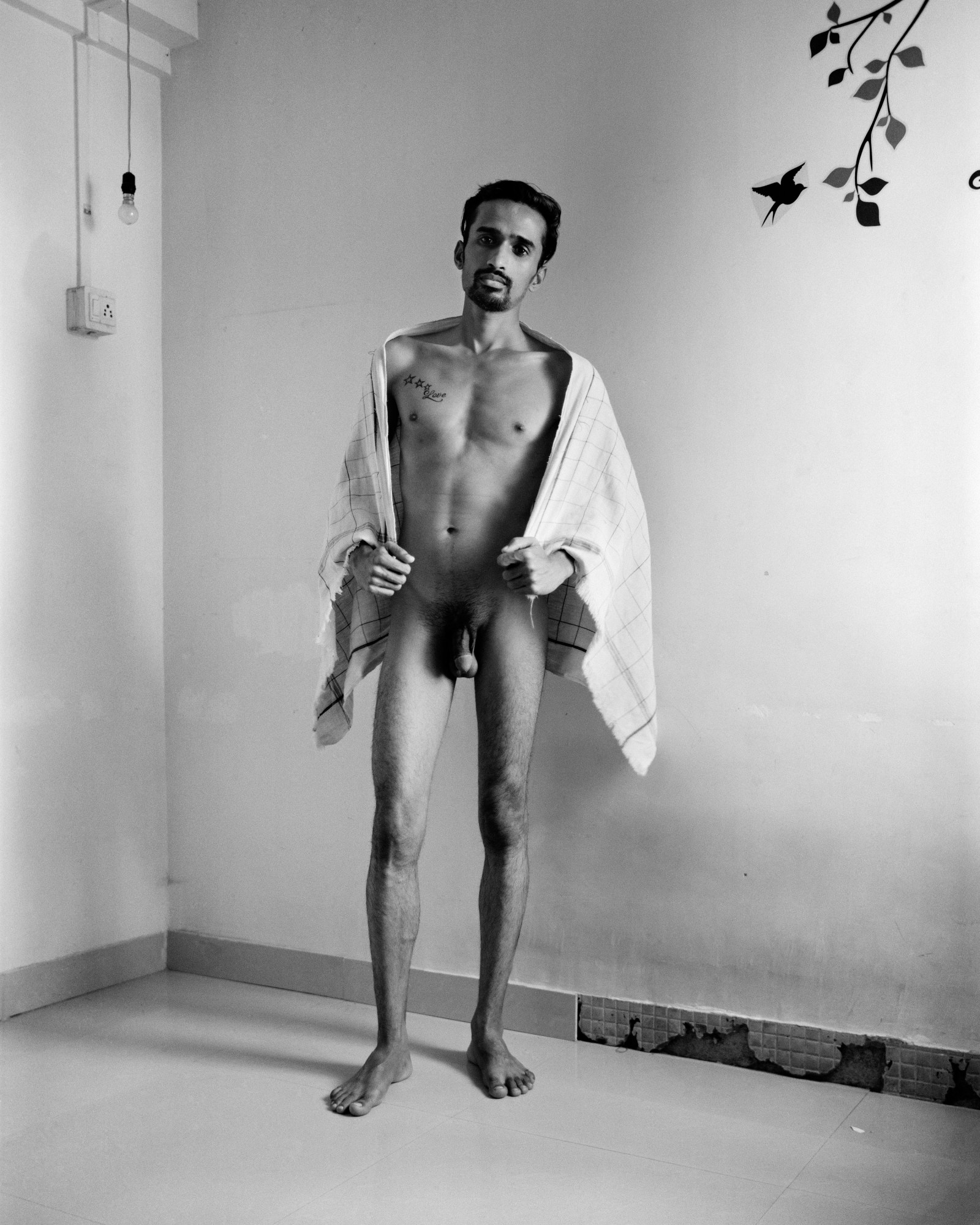

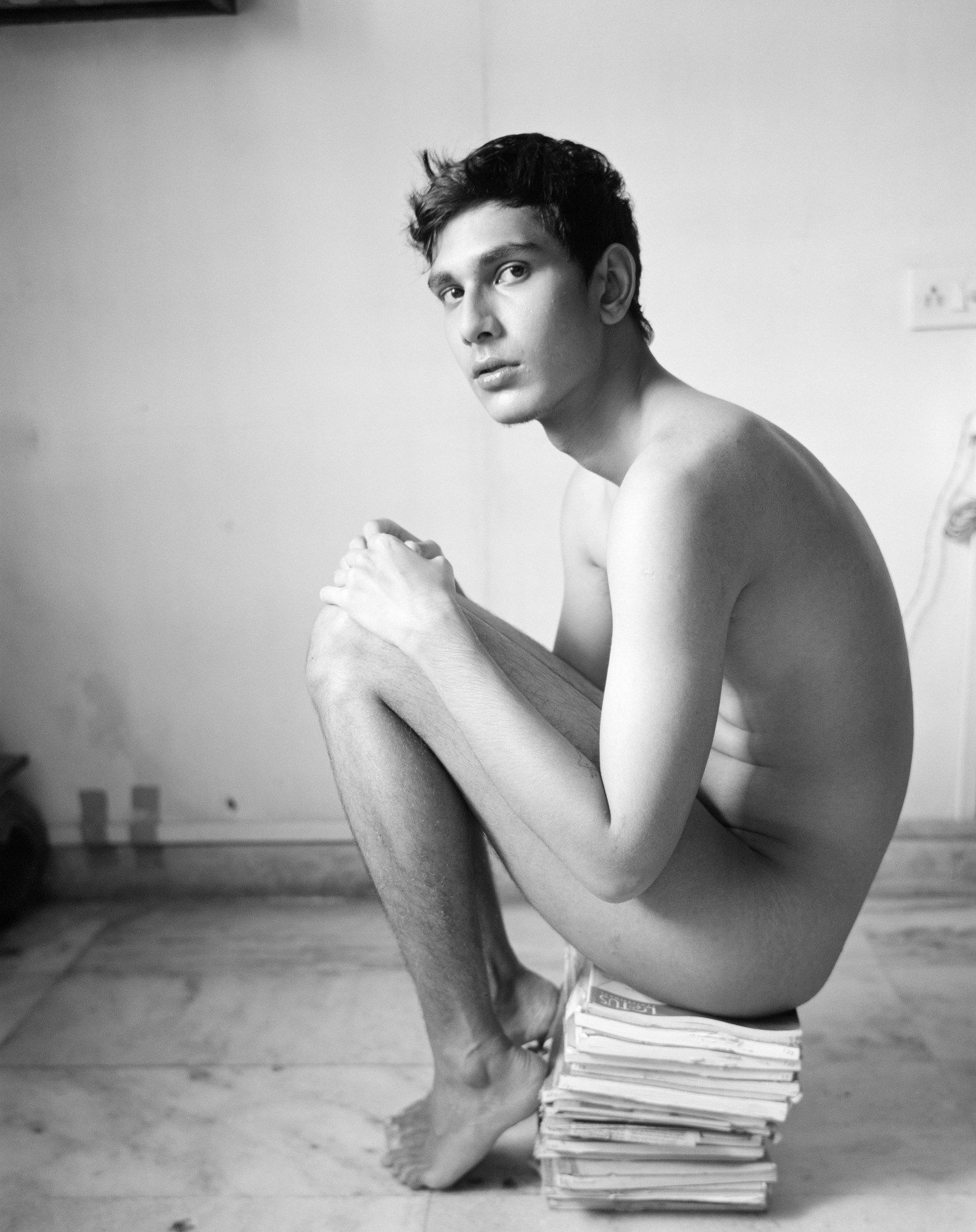

A little while before this happened, Olivia Arthur, a documentary photographer with Magnum, was commissioned to create a series of images with Indian photographer Bharat Sikka by a photography festival in Mumbai exploring LGBT+ scenes. The aim was to take a dual look at different communities in the UK and India; the final show comprising of Olivia’s work in Mumbai and Bharat’s work in Brighton. In Private/Mumbai, Olivia’s final collection of images meditates on moments of solitude in a city of over 22 million people. “I wanted to show, the boldness and strength of the people who have had to fight to be able to be open and to be comfortable in their own skin,” Olivia explains. “Some of the subjects I met relatively briefly for a more formal ‘portrait session’ and some I have developed longer relationships with, photographing them several times and continuing to see them in between. More than anything, I was in awe of the people I photographed, how comfortable they are in their own skin and the strength that they seem to have.”

The biggest challenge she faced following weeks of shooting was not trepidation from her subjects, but instead the festival itself. “I had always been open with everyone about what I was doing and the fact that we would be having an exhibition in the city and they were proud to be part of it. Then the festival was nervous about how the local government might react to some of the images.” Now showing as part of Magnum’s The Body Observed exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, we spoke to Olivia about working on this project and what she learnt along the way.

What was the starting point for In Private/Mumbai?

This actually came out of a commission for a photography festival in Mumbai to photograph, in Mumbai and in Brighton, these communities, in collaboration with Indian photographer Bharat Sikka. I had always wanted the work to include people who identify with any sexual orientation, because I feel that being open about sexuality is a challenge for most in what is a religious and culturally conservative place. Of course, the LGBT communities have faced more discrimination that most, and have been subject to regressive colonial laws so they have had to push harder. In a way that is what I have wanted to show most here, the boldness and strength of the people who have had to fight to be able to be open and to be comfortable in their own skin.

Many of these photos were taken on the cusp of the decriminalisation of homosexuality, was there a sense of this happening among the people you photographed? Was there a noticeable air of change, or just a detachment from politics?

Many people talked about how things had become easier and more open, but they were more interested in how different communities are able to connect and meet, and the role that social media has played in that. The legal part is obviously a huge victory for this community but there are still many conservative people and it will take longer for the culture and attitudes to change too. So the issue is out of the criminal sphere and that is so fundamental and an important signal, but the day to day issues and discrimination don’t go away overnight.

You choose to centre the project around privacy, did many of your subjects live completely open lives?

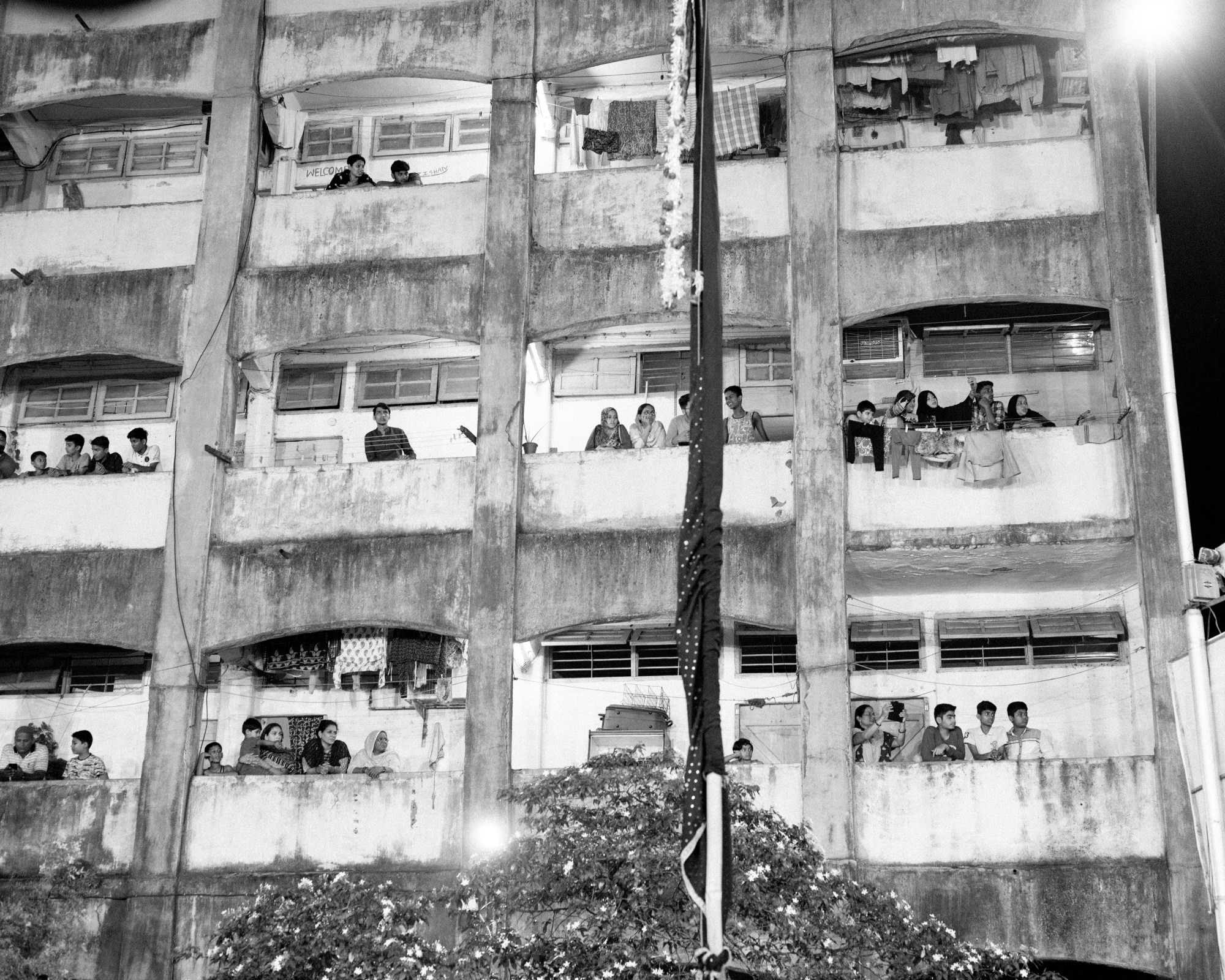

I think the issue of privacy is a very complicated one in India. Having private or personal space is not something to be taken for granted. Mumbai is an overcrowded, throbbing and physically close city. Many families live in houses that don’t have private space for everyone. In public, and particularly on public transport, people are forced to be uncomfortably close. I began by looking for people’s private space and asking if I could photograph them there, with the idea that it would be the place where they are most at ease, most able to be themselves. But I soon became aware that for many people there is no privacy at home at all. And you see all over the city that for many couples, the place that they can be most private, most free with each other, is far from home in an often very crowded place. There are spaces by the sea front, along the sides of the highway and other crowded places where young people come to find their moment of privacy. I became fascinated by this contradiction of private and public spaces.

Was there a significant difference in the lifestyles and outlooks of elder LGBT+ subjects compared to the younger ones?

One of the people I photographed was James Ferriera, a well known fashion designer and older member of the community. James has always been open about his sexuality and is very comfortable with who he is, but I imagine is more unusual in his generation. Though I think in terms of divisions, the class divide is probably more stark than the age divide. I think it has always been easier to be more open in the richer classes, and in the poorer communities it is particularly difficult to get away even if you want to.

Did the sense of community among queer people transcend cultural divisions?

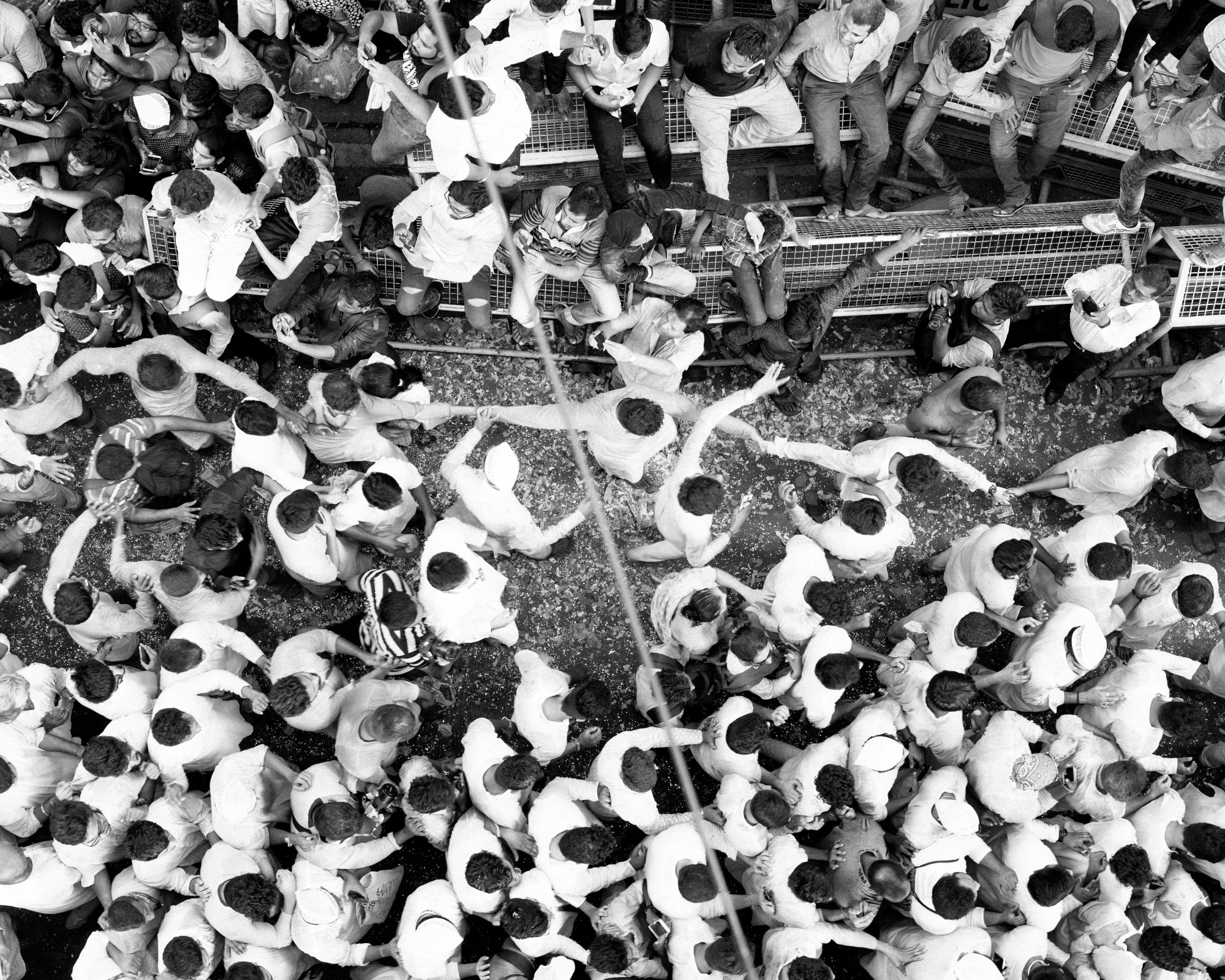

I photographed many different people for this series and they came from many different backgrounds, not one community at all. At Queer Azaadi (Mumbai’s gay pride) I did see a lot of the people that I knew from many different places, but there were also plenty of people who are not part of that and that I had met and photographed outside of any community.

What camera did you use? India is a country known for bright, vivacious colours and classically in photography this is exaggerated. Why did you shoot the series in black and white?

This is all shot on large format, both a Linhof (for the portraits) and a Graflex with a flash (for the handheld shots). I shot on black and white film and processed most of the film myself at the place I was staying. I love the slowness of this very classic approach and I have always felt that photographing like this is more honest because the process of putting the portrait together takes time, there are no surprises, you’re not catching a moment of grabbing a shot.

Can you explain the story behind this image above?

I photographed this couple at their apartment one morning and they agreed to do a nude picture together. In this kind of situation the kind of picture I make completely depends on how relaxed they are with my presence and with each other. In this case they were very comfortable and there was a great tenderness between them, which I have tried to capture here. If it looks like something more sexualised, then that is a mistake on my part and not the intention of the picture.

Arundhati Roy’s recent novel has brought more attention to Hijra communities (India’s “third gender”). With Mumbai did you get a sense of how much existing awareness there was towards LGBT communities among local residents?

The Hijra communities are an ancient part of the culture in India and well known there, so Roy’s novel has probably brought the awareness outside the country more than within. Everybody knows these communities and, of course, have many different attitudes towards them and everything that goes with them, but it is important to stress that there are also many transgender people who are not part of them and don’t want to be. Hijras leave the communities that they are born into and become part of this other ‘family’ but there is also the need for the option to be transgender and stay in ones own family. I photographed a dancer, Shivali, who is transgender and continues to live with her mother.

Is there a photo that has a particular significance to you in the series?

It’s more the series that is important to me than the individual images, the combination of the feel of the city juxtaposed with the calm strength of the individuals.

What makes a powerful image?

Something that lingers in your mind long after you’ve finished looking at, or that you want to keep coming back to.

‘The Body Observed: Magnum Photos’ runs 23 March – 30 June 2019 at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts

Credits

Photography © Olivia Arthur | Magnum Photos