This article originally appeared on i-D US.

Daigo “Johnny” Yamashita remembers first encountering rock and roll with Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit, “Johnny B. Goode,” when he was 16 years old.

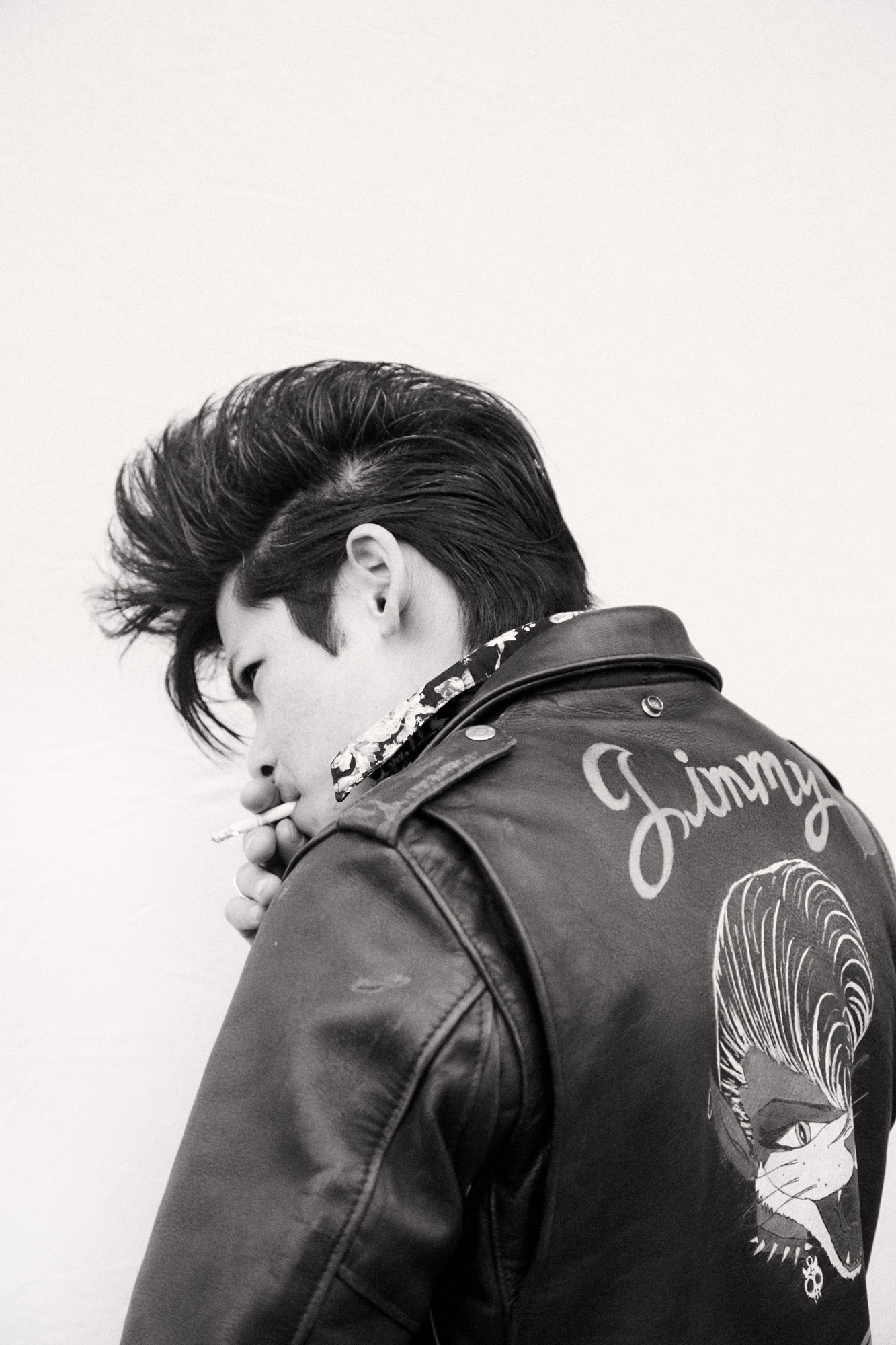

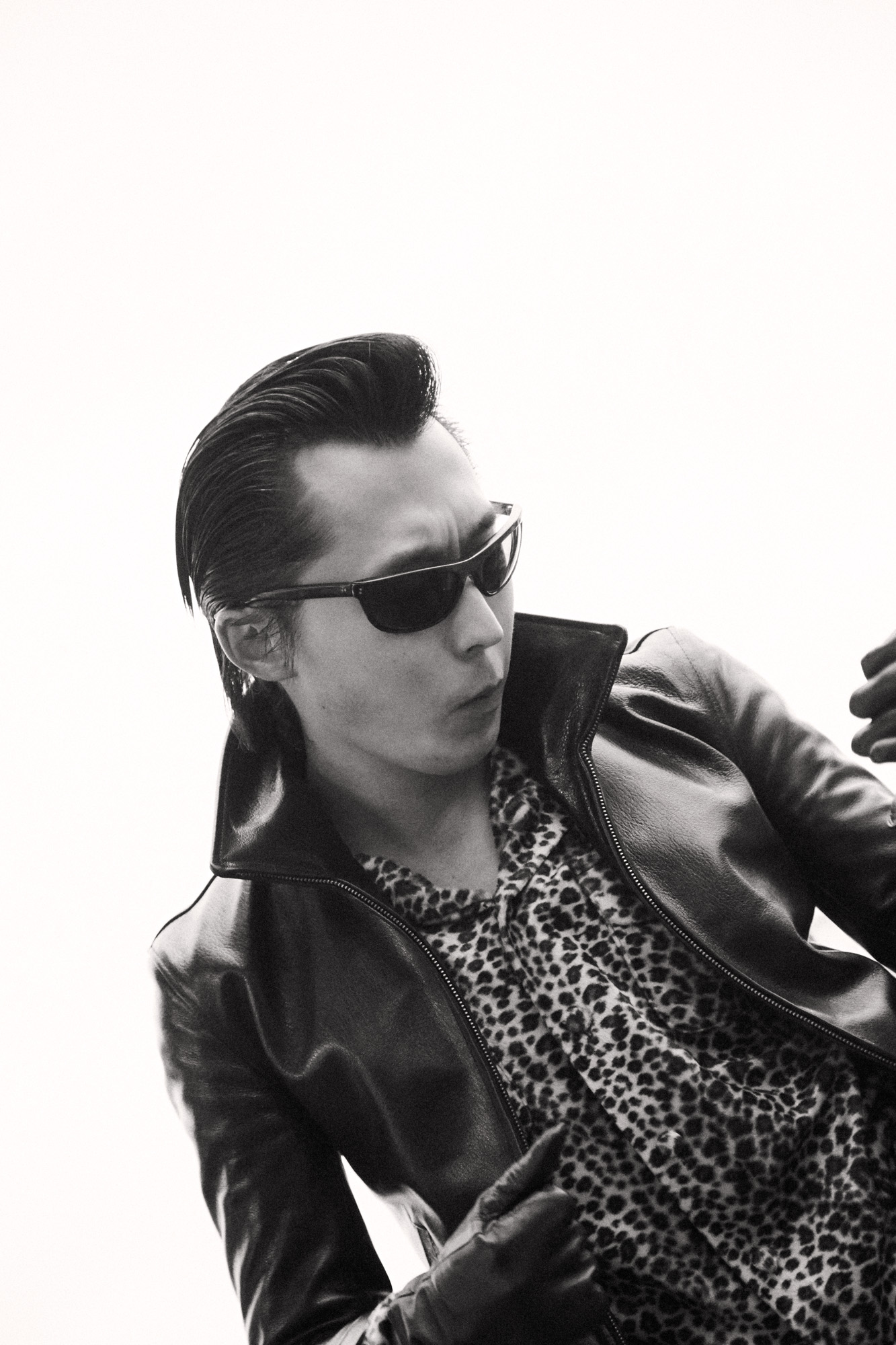

Without any friends who shared his obsession for rockabilly fashion, Yamashita began mimicking the Greaser-style ducktail hairstyle and leather-heavy outfits that he saw in old magazines and movies. His biggest inspirations were Tomayasu Hotei, the Japanese guitarist famed for his rendering of the Kill Bill theme song, the Japanese band Carol, and a dreamy Johnny Depp in Cry-Baby. A friend taught him how to dance the Twist when he was 18.

A mash-up of rock and roll and country music, rockabilly was first popularized in Japan in 1955, when a cover of Bill Haley and His Comets’s “Rock Around the Clock” by the Japanese singer Chiemi Eri topped charts in the country. The kaminari zoku, an urban motorcycle gang prominent in the 1950s made up of Japan’s proletariat, can perhaps be credited with bringing the earliest incarnations of the Greaser-style kitsch that now characterizes the subculture to the country.

The genre quickly died out in the 1960s, when postwar political crises led to renewed fears about American influence over the country, but, like in the US, Japan saw a huge Oldies revival in the 1970s and 1980s. Bands like Carol and The Cools brought leather, slicked-back hair, and motorcycles back into the Japanese vernacular. In the 1980s, The Black Cats introduced the slicked-back, ducktail hairstyle (the same one that Yamashita would learn to mimic decades later) to the country.

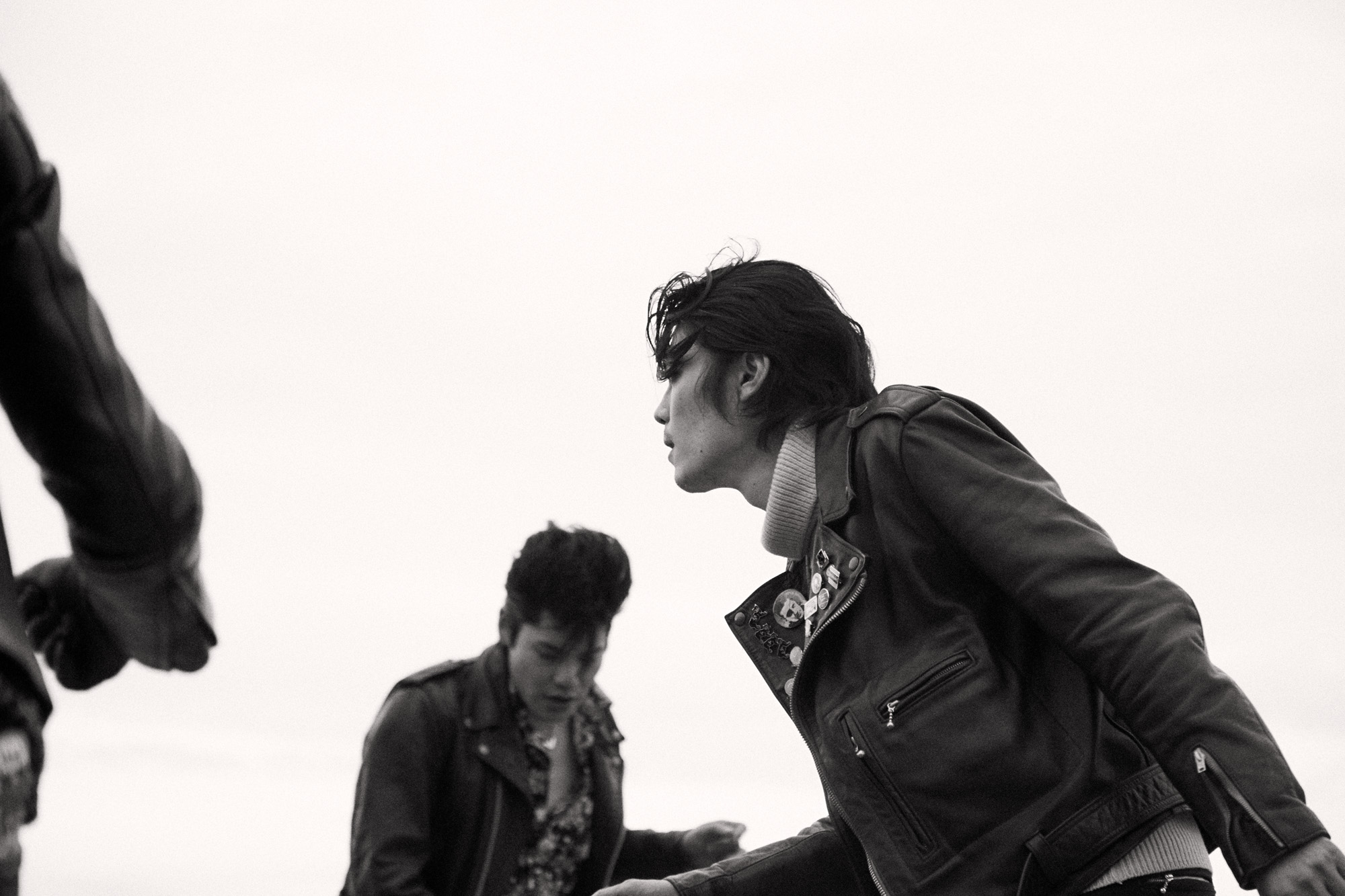

With rockabilly’s re-found popularity came the extreme reimagining of the fashion, most of which, up until a few years ago, were most commonly found on rockabilly enthusiasts dancing near the entrance of Yoyogi Park in Shibuya, Tokyo. Photographer Alvin Kean Wong was struck by rockabilly culture when he first traveled to Japan from Singapore as a teenager. “The rockabillies performing in Yoyogi Park represented a rebellion against anything conservative — something I was very attracted to as an Asian from a conservative background,” Wong said.

In late 2017, when Wong began formally doing research on rockabilly culture in Tokyo, his Japanese friends warned him about it being a dying subculture. “I began searching the Internet in a mad frenzy for anything related to rockabilly culture in Japan,” Wong said. He found Yamashita through Instagram and direct messaged him, “thinking it was a long shot.” When Yamashita replied one week later, Wong immediately booked a flight to Tokyo.

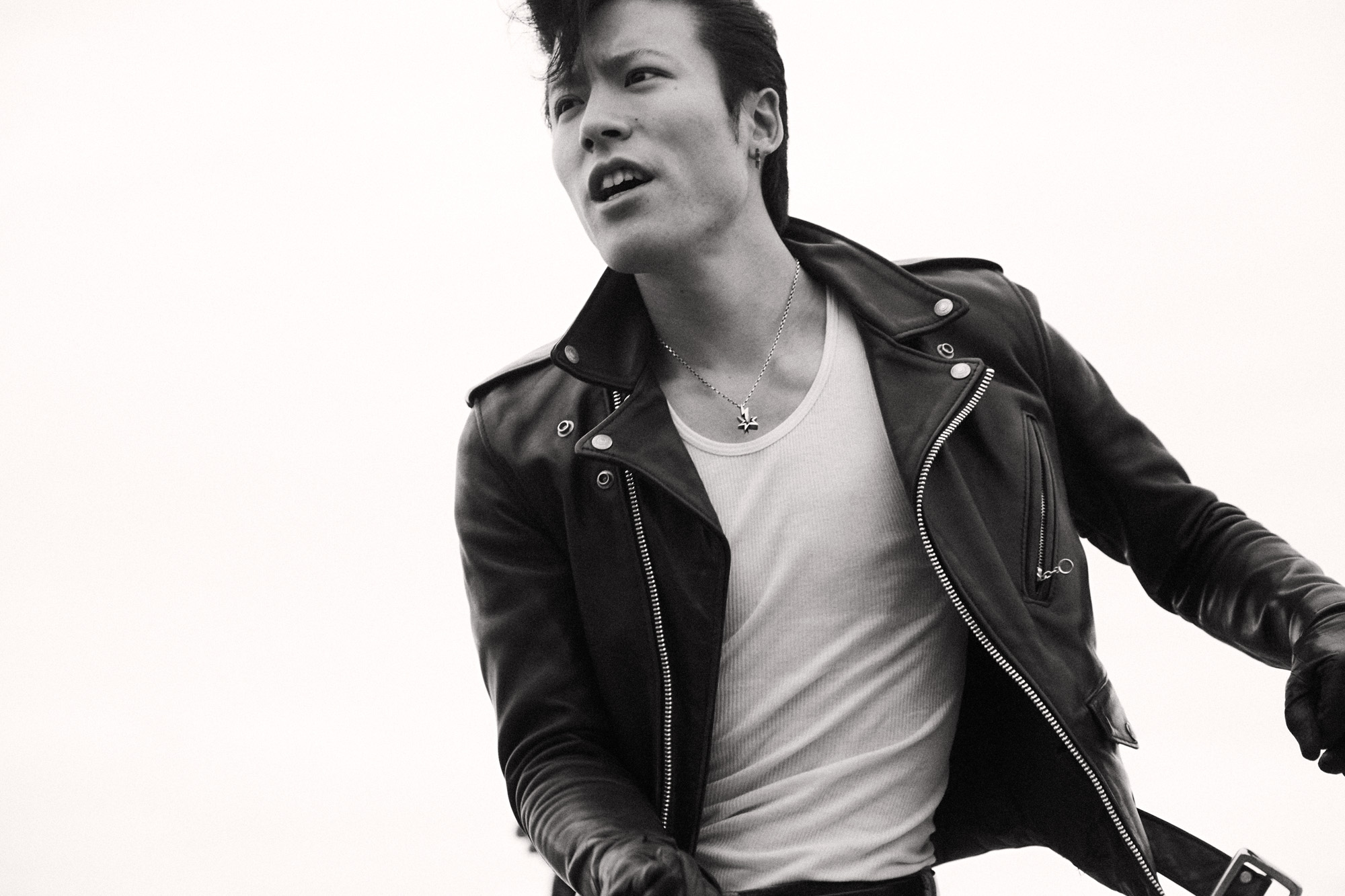

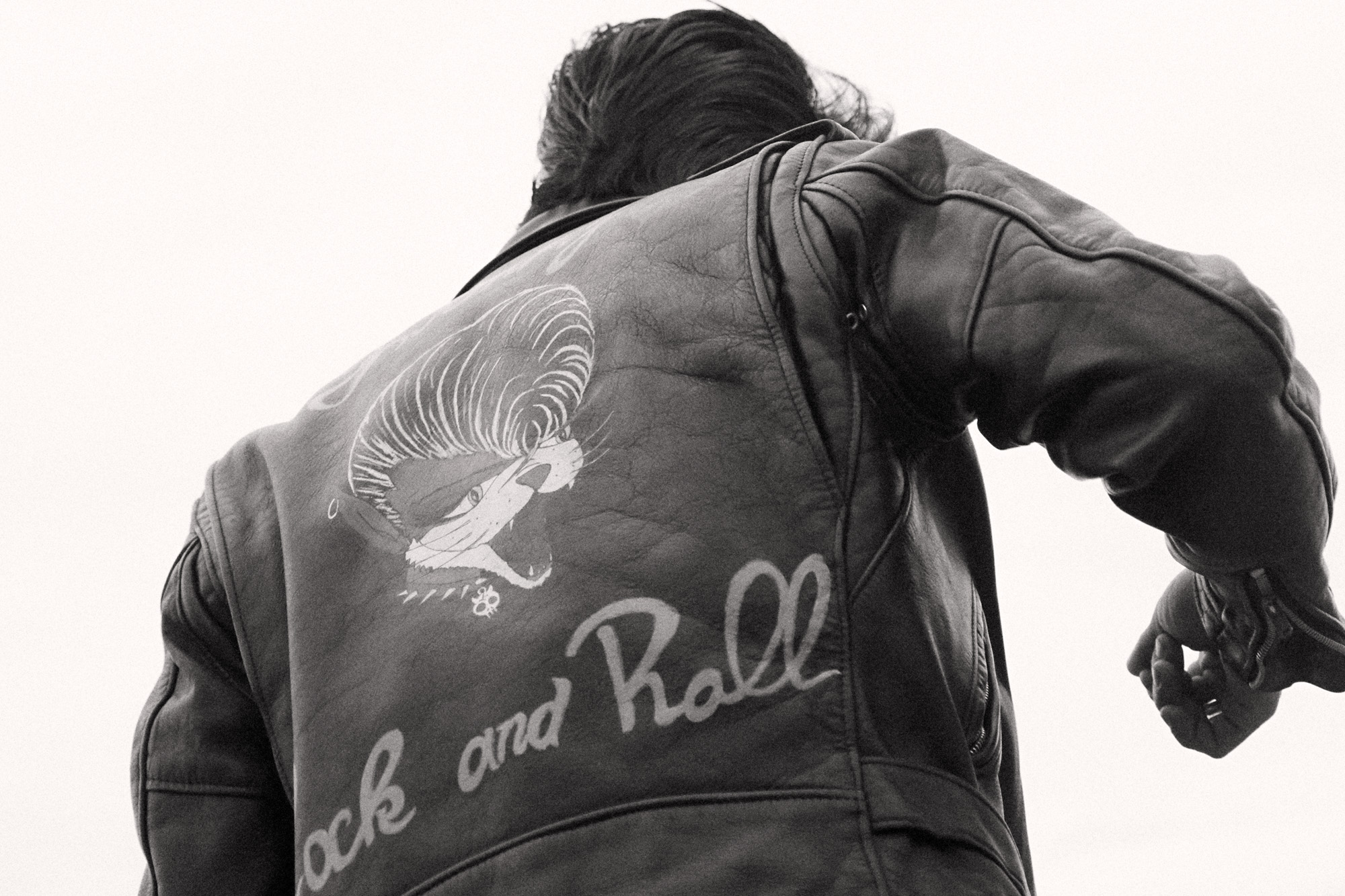

Over the years, Yamashita has become somewhat of a rockabilly icon in Japan — amassing a collection of almost 20,000 followers and 15 leather jackets. He was nicknamed Johnny, “the most famous rockabilly name” as he puts it, when he was working at a 1950s-style bar named Johnny Angel many years ago and hasn’t let go of the name since. He and his band, Johnny and The Pandora, perform every weekend at Yamashita Park in Yokohama, a city slightly south of Tokyo, and have toured in festivals around Canada, France, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore.

When I asked Yamashita what he would call his form of making a living, he said, “I’m a musician, but I’m also an actor, dancer, and model. So I wanna say my employment is just rock ‘n’ roller.”

The crew meets and performs in Yokohama as opposed to Yoyogi Park, where, Yamashita tells me, rockabilly culture remains “a symbol of ‘bad boy’ past in Japan,” rejected by older generations because of the genre’s association to the kaminari zoku, open sexuality, and drugs. “I believe we can change that,” Yamashita said.

Above all, Yamashita is committed to changing the notion that rockabilly is yet another style subculture of Harajuku, aware of the danger of being a musical culture known better for its fashion than its music.

Wong met the rock and rollers while they were dancing to the likes of Elvis, Carl Perkins, and Chuck Berry in Yamashita Park, proving that fantasies of mid-century Americana are alive and well in the Japan. “I hope that my photographs translate the vision of freedom and joy that they embody,” Wong said. “Asian rockabillies have always been heroes I could relate to.”