Statistics around rape and sexual assault always make for bleak reading, no more so than when it comes to rates of reporting. Research indicates that just 15% of women report their attacks to the police, while less than a third of young men prosecuted for rape are ever convicted. Even when complaints are brought to court, it’s still an uphill battle for many women. Complainants frequently face disbelieving police and an unsympathetic legal system; 75% have their sexual history brought up by the defence. It’s clear that something has to change.

But now, a new wave of apps are attempting to use technology and biometrics to make reporting assault easier, and less traumatic for victims. Spot, created by UCL neuroscientist Julia Shaw, “combines memory science and AI to tackle harassment and discrimination”. Callisto, set up in response to an epidemic of assault on campus in the US, works in a similar way. Both are intended to make disclosure easier, safer and less traumatic for victims of harassment and assault, Spot focusing on workplace harassment and organisational change, Callisto on campus assault.

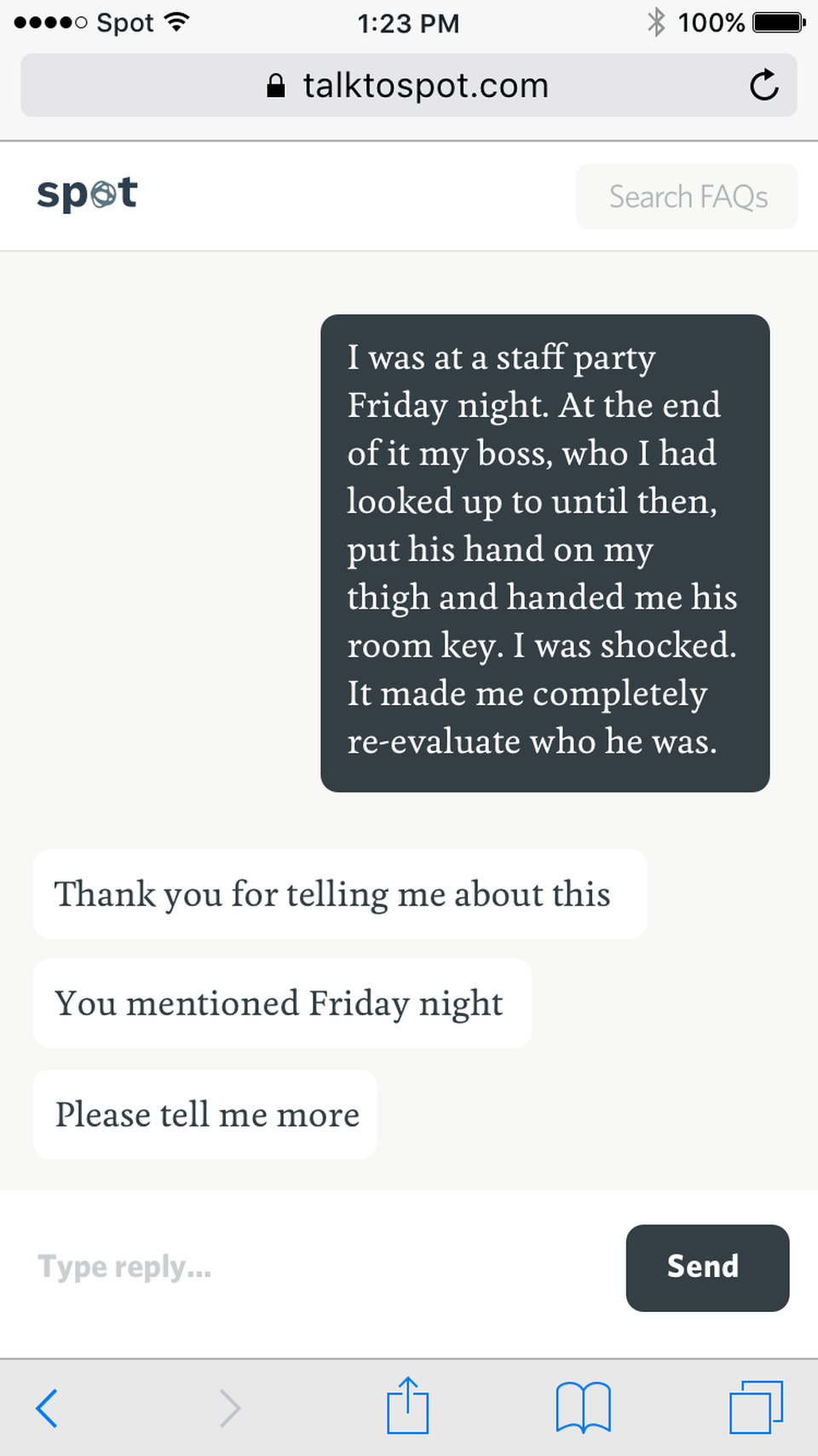

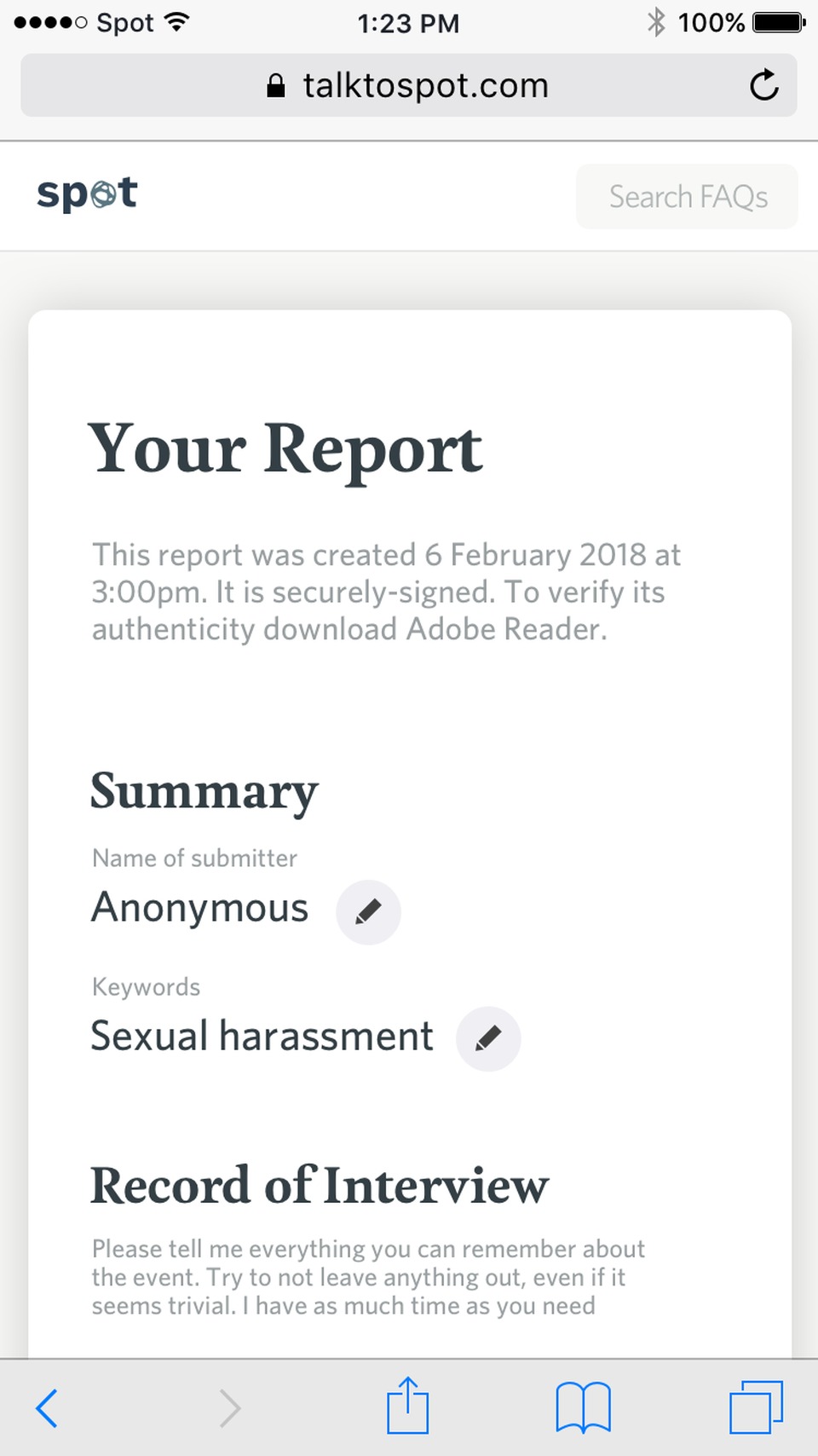

Spot uses a chatbot to talk to victims, using an interview technique called the ‘cognitive interview’ (a widely used police interviewing technique which uses memory markers to provide a complete eyewitness testimony of an event). “As part of my work, I trained police on how to properly conduct interviews around important emotional events,” Shaw says. “It lead me to realise how easy it is to not remember important details. What I thought people needed was a way to contemporaneously create a really high quality piece of evidence that they could use if they wanted to take it further and make a complaint to their organisation.”

As Shaw says, memory can be a slippery thing: there’s often a discrepancy between how people are questioned and how they actually remember things. This is particularly true in cases of assault; traumatic memories behave differently to normal memories, often encoded in “rich detail” but without temporal context. Those who experience dissociation during a sexual assault are also more likely to have fragmented memory – and with memory so important when assaults are taken to court, helping victims record their recollections as best they can could be key.

“The sooner you record something, the better it’s going to be in terms of quality,” Shaw says. “And the more weight it’s going to carry in terms of telling other people that this is what happened, and this is what you remembered at the time.” As a piece of evidence, this can be vital. Shaw’s work as a memory expert frequently brought her into courts of law, where she was tasked with judging the strength of certain memories. A record from Spot, she says, would be as “high quality as you can get, basically”.

Memory is “absolutely crucial” when it comes to witness statements, Peter Wright tells me. Wright is managing director at Digital Law, a UK firm specialising in digital issues. Wright points to the often horrific experience of being cross-examined by the opposing counsel. “It can sometimes be a rather aggressive and detailed and traumatic experience,” he said. “It’s enough to put an awful lot of complainants off coming forward, knowing they may have to go through that.”

But apps like Callisto and Spot, which provide best-practice statements, could help a victim feel more confident and comfortable, Wright says. “What I’d be interested in with regards to these apps is how they help the victim make an assessment in terms of how comfortable they are relying on the evidence they have,” he explains. “And I’d be interested to see if it prompts the victims to try to come up with other evidence, too.”

This is something that Anna*, 28, also mentioned when discussing her experience of reporting. “If I’d had something that had prompted me to gather my memories in the way that some of these apps do, then yeah, I would have felt a lot more confident reporting my assault,” she says. “As it was, I didn’t know what to do with what had happened, whether I should write it down or not, what details I needed to include – I was completely lost.”

“Maybe the most traumatic thing that can happen to you has happened. But are you believed?”

Anna was assaulted by someone she knew – so, in addition, she felt that she wouldn’t be believed. As Wright points out, questioning can be “aggressive… and traumatic” – and this is exactly what Anna expected. “Obviously testimony from an app or from wherever else wouldn’t have changed that,” she said. “No matter how confident I was, if the questioning was horrible it would have been horrible. But I do think that having it written down and clear in my head would have made that prospect a lot less frightening.”

But how would such a statement stand up in court? “The defence would be within its right to examine the algorithms that the apps are based on, and whether those algorithms are weighted in favour of a potential victim,” BLM Law’s Iskander Fernandez explains. “There’s an ongoing debate around bias in artificial intelligence across the legal profession.”

“Questions would also be posed about what the chatbot is asking, again to ascertain whether the questions are weighted in favour of the potential victim. Whilst there’s a strong argument in favour of making it easier to make an allegation where this kind of offence is underreported, the devil is in the details and in the working of the app itself.”

While technology might be able to bridge the gap between incident and police report, what technology can’t do is change the wider culture around sexual assault, activist and filmmaker Jade Jackman says. Jackman’s current project, Station, is a “Kafkaesque look at the absurd and sinister flaws in a legal system that is supposedly designed to protect us”. The film uses testimonials from survivors of assault, explaining why they haven’t reported or explored the problems they faced; Jackman describes it as a “collective voice” exposing “the horror of what many women face when they report rape”.

“To me, it appears like the end goal of these apps is still to report it, to the police or workplaces or schools,” she says. “And while it might help someone to that first step, they don’t really seem to address the fundamental issues that society has with believing survivors, or the ways that the legal system doesn’t fit the reality of reporting.”

Jackman compares such tech to the Time’s Up legal fund – well-meaning, but still fundamentally ignoring the root causes of the problem. “In my experience it seems that lots of survivors find it helpful to communicate their experience for the first time in a digital sphere, rather than having to have contact with another person, so that’s definitely a benefit,” she says. “I’m just very sceptical of anything that purports to help end sexual violence without really eliminating the root causes of low reporting rates.”

There are also, as Station explores, deep issues in the legal process. “There’s huge mistrust in the system for a myriad of reasons,” Jackman concludes. “So there are a lot of social factors that need to change if we want to improve reporting rates. There needs to be an actual social conversation to accompany all of this.”

“Maybe the most traumatic thing that can happen to you has happened,” Wright says. “But are you believed?” Anna tells me that the reason she didn’t report her assault comes down to the fact that “the legal system doesn’t care about women”. “I don’t think it believes women, I don’t think it takes women’s traumatic experiences as seriously as it should,” she says. “I’ve had friends report [all kinds of assaults] and, overwhelmingly, they’ve had horrible experiences from start to finish. Why would I put myself through that?”

This gets to the heart of the issue. Technology can be a vital tool for victims, both women and men – it can keep track of us and keep us in contact with people when we need them, and can provide a way to communicate what has just happened to us, too. But issues around reporting run deeper than this. Apps like Callisto and Spot are good ways to boost someone’s testimony, to help them remember things more clearly and in greater detail, to provide them with quantifiable and best practice ways of disclosing whatever they’ve been subjected to.

No matter how good they are at this, however, those biases within the criminal justice and legal system still exist; low conviction rates still exist. The concept of believing survivors is still alien to many people: you only have to look at social media comments around high profile cases of rape and assault to see this. To truly tackle sexual assault, it’s these areas that need to change – and, as well-meaning as they are, no app is going to do that.