This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Homegrown Issue, no. 355, Spring 2019.

“I make things and I leave defining what that is to someone else,” Virgil Abloh asserts, looking up from his iPhone in the cream-carpeted headquarters of Louis Vuitton in Paris. “There are lots of ways to describe what I do: architect, artist, graphic designer, clothing designer, creative director, art director, stylist, filmmaker, photographer, DJ… I’m not interested in focusing on one thing.”

To say that the 39-year-old is simply a fashion designer would be like calling Louis Vuitton just another luggage manufacturer. It’s bigger, more symbolic than that. Both names stand for a wider culture; a sense of community; an ideology; a lifestyle. If his debut Louis Vuitton show in June last year made anything clear, it’s that the winds of change the designer has ushered in have energised the fashion industry beyond belief.

Set in the gardens of Paris’s Palais-Royale, the 2,000 guests (600 of whom were students from fashion, art, design and architecture colleges around the world) watched as 56 models from a truly diverse range of cultures came down the 200-metre rainbow-hued catwalk. It was a bright, sunny afternoon set to live jazz from Toronto instrumental band BadBadNotGood. Many of the models were familiar faces: Playboi Carti, Blondey McCoy, Octavian, Steve Lacy, A$AP Nast, Dev Hynes and Kid Cudi. The show was titled We Are The World after Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie’s 1985 charity single in support of Ethiopian famine relief. Kanye West was there and he and Virgil shared an emotional hug after Virgil’s bow. Despite the monumental scale, it felt like an intimate family affair.

“This isn’t Kansas anymore. We are now in a new place where the world is different,” Virgil says, reflecting on the collection’s two main concepts: white light hitting a prism and refracting into the full spectrum of colour, and the 1939 camp classic The Wizard of Oz. Both are fairly literal metaphors for Virgil’s journey down the Yellow Brick Road, and the significance of his appointment as the first African American head of Louis Vuitton, only the second black Creative Director at an LVMH brand ever (British-Ghanaian designer Ozwald Boateng joined Givenchy in 2003).

“The idea of modernity speaks to my beliefs about inclusivity and being open-minded and respectful to people from all walks of life,” Virgil says. “That is at the heart of what I am pursuing in my own work. In this position, at this brand, there is a responsibility to represent what society could be.”

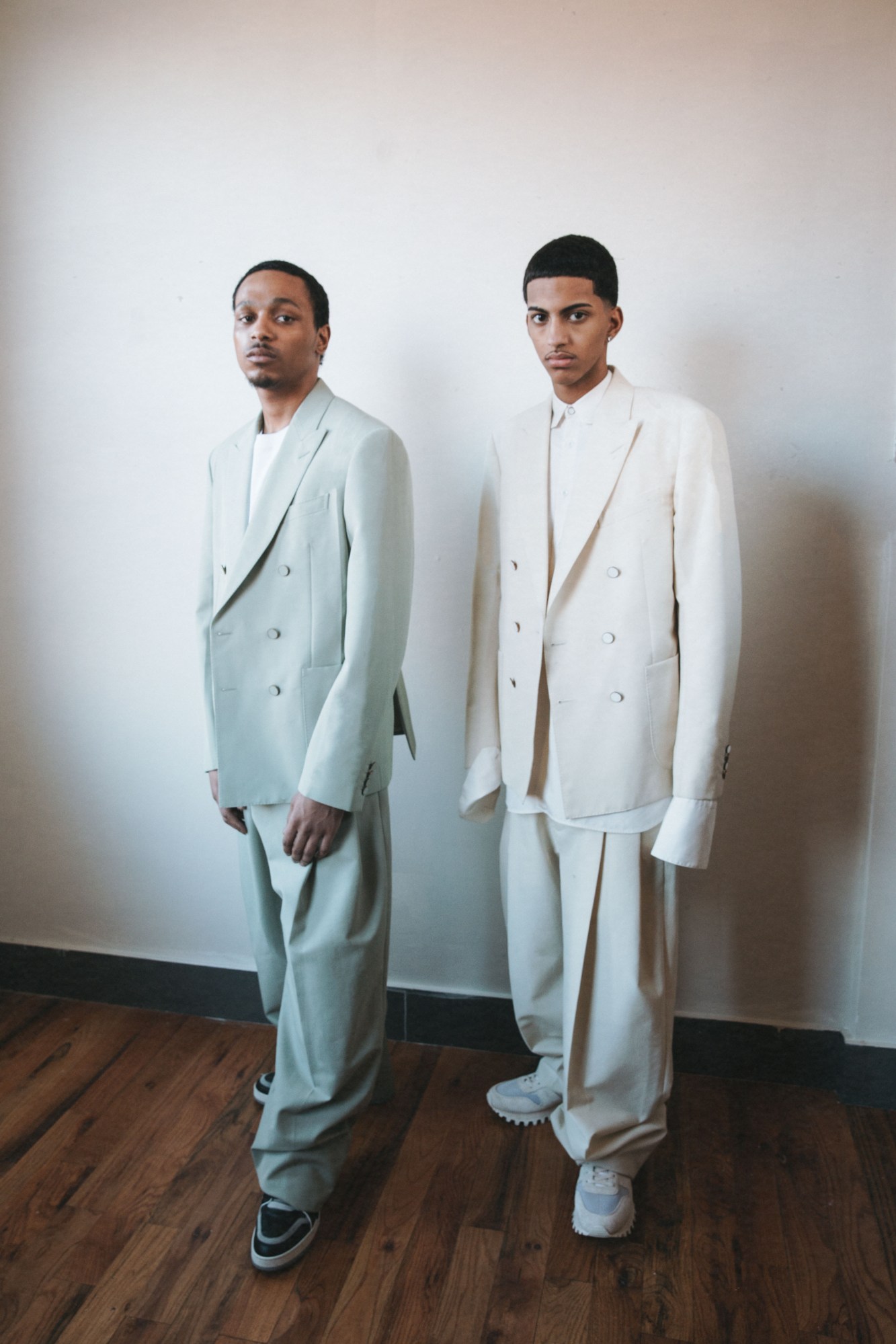

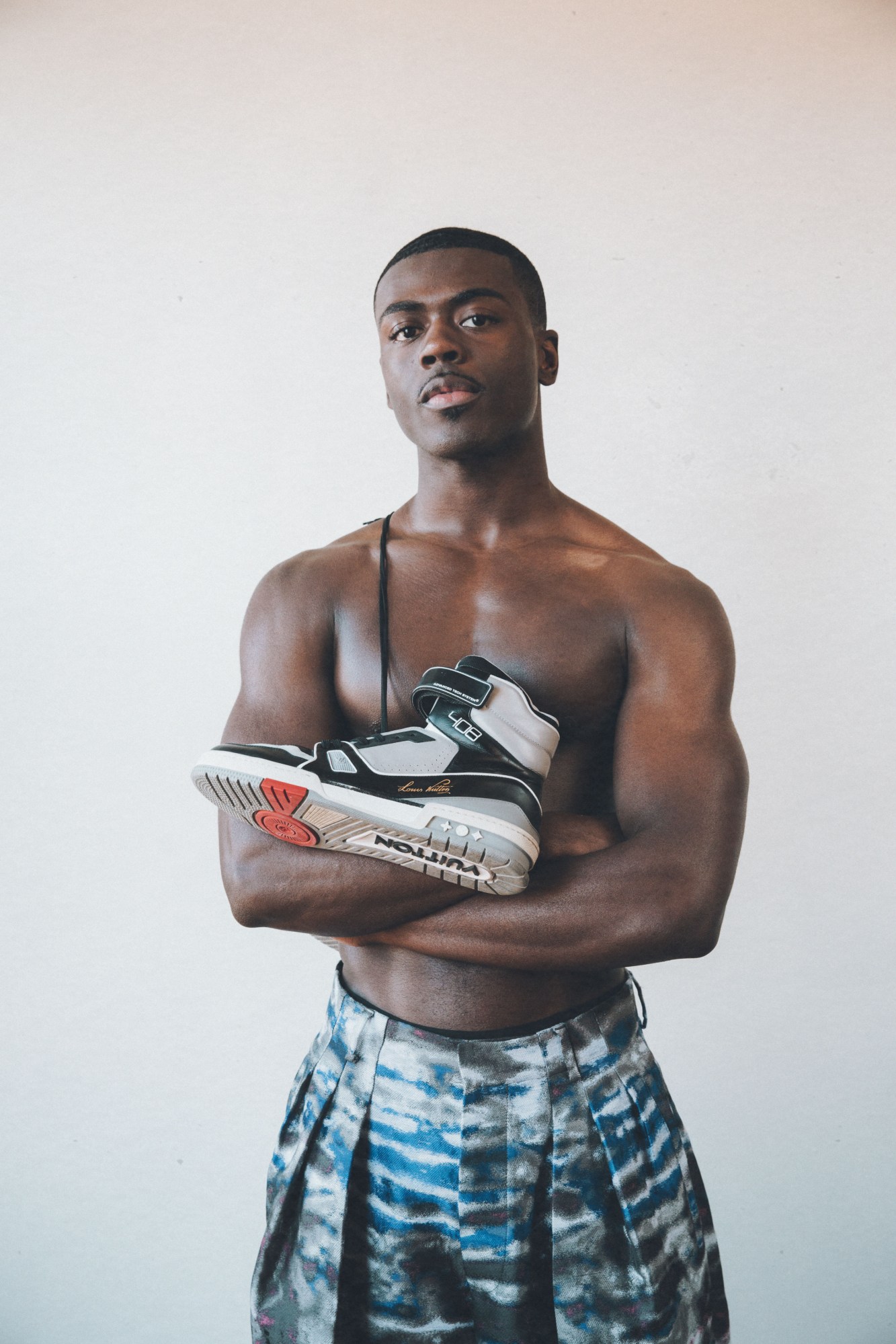

The clothes that went down the runway that day were only half of the story. The bright, hyper-saturated line-up introduced such thought-provoking sartorial concepts as the slouchy layered Zoot suits, the “accessomorphis” bag-garment-harness hybrids, the dude-ish tie-dye sweats and LV-monogrammed see-through PVC bags. But the collection was imbued with a heightened sense of euphoria because of what it meant to a generation of digitally-engaged millennials and young POC. They are now part of the fashion establishment; their culture is valid.

“It’s really about a dialogue,” Virgil explains. “I wanted that first show to be remembered as a new foundation and left as an open book.” In terms of the clothes and the gravitas of luxury associated with a brand like Louis Vuitton, it came down to doing something different, something that wasn’t expected of him. It focused heavily on tailoring and luxury “accessomorphis” harnesses, which would prove to be a winner on the red carpet. “I’m interested in adding romanticism to menswear. A feminine touch. A softer edge. Luxury can be insinuated as many things, but I’m trying to make things that people covet and desire.”

So how did Virgil Abloh make it to Emerald City? In 2002, he completed his degree in civil engineering and moved on to a degree in architecture in Illinois. Fresh out of college, he orchestrated a meeting with Kanye West’s then manager John Monopoly, who hired him on the spot. Over time, Kanye and Virgil embarked on a mission to break into the fashion industry, interning together at Fendi in 2009. The following year, West named Abloh Creative Director at Donda, his creative agency.

Virgil’s first love is music, and his experience as a DJ, which stretches back to his teenage years, is symptomatic of his approach to fashion: sampling classics and moving across genres to create something completely different to the original. “DJing is like going to the gym and doing the collections is the Olympics,” he explains. “DJing uses the same part of the brain as fashion design, you want to make a whole room of people come to the same consensus and feel enjoyment from it.”

Virgil’s career as an independent fashion designer began by launching a streetwear label called Pyrex 23 – Pyrex a reference to the glass used in crack pipes; 23, the number on Michael Jordan’s jersey, stood for basketball – which he shuttered just after a year. In 2014, he launched Off-White with the help of Marcelo Burlon of the New Guards Group, a sort of mini-conglomerate of streetwear labels such as Heron Preston and Palm Angels. His Helvetica-branded, slanted-striped designs – often with the word of the item in quotation marks – seemed to skyrocket in tandem with the rise of Instagram culture. Part of his strategy was to collaborate with as many other brands as possible, accessing their client base and bolstering brand awareness for Off-White.

To put it into perspective just how quickly it all blew up for Virgil: in 2015, he was shortlisted for the LVMH Prize for Young Designers. Less than three years later, he was given the top job at a luxury group’s titular flagship.

Today, Virgil is frequently described by his collaborators as the busiest man they know, more so now that he is at the helm of two brands, as well as undertaking countless collaborations and working on a career-spanning retrospective entitled “Figures of Speech” opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago later this year. How does he compartmentalise it all? “Off-White is having a dialogue with my 17-year-old self and Vuitton is having a dialogue with a brand from 1854 – there’s a history and a reverence to it,” he explains. “Thinking of an idea, making a pair of pants, and designing a runway show are all different because they all sit on different foundations.”

For every superfan hanging off his every sentence, Virgil also has his fair share of critics too, something he takes in his stride. “I’m focused on articulating my ideas and then stacking those up against the ones I’ve had since I was 15, when my career and creativity began,” he says. “Dwelling on those things equate to nothing in terms of my practice. My practice is tied to a dialogue with itself. That’s where it all lands.”

He’s not picky when it comes to who he wants his designs to speak to; he’s aiming to convince everyone. “I like to make things that are relevant to the kids browsing in stores and to the purists who don’t like anything — I don’t want them to just sit on a shelf per se.”

Virgil has previously attributed one of the central tenets of his approach as the “readymade”, a term coined by artist Marcel Duchamp in 1915. Duchamp would take found objects, such as a porcelain urinal or a bicycle wheel and recontextualise them as artworks simply by placing them in art galleries. The effect is to create something familiar yet unexpected. Virgil uses his DJ’s instinct to splice sartorial genres. “Skateboarding and hip-hop dictated what I thought was cool when I was growing up,” he explains. “Now everything is more spread out. Hip-hop has influenced preppy styles of dress; rock ‘n’ roll has mixed into hip-hop. We’ve got a melting pot of different styles and cultures.”

It is a philosophy that resonates with a generation who grew up on MTV, juxtaposing sportswear with luxury logomania. “Nothing upsets people more than when they don’t understand it,” says Benji B, the Radio 1 DJ who has worked with Virgil for almost 15 years and is now scoring Louis Vuitton’s menswear shows as the brand’s official Music Director. Previously, he worked with Phoebe Philo at Céline. “It’s not something that immediately fits the model of the self-fulfilling structure. You could apply that to major record labels, too. There are buildings of people working out how to keep these models together, but today artists are more in touch with the consumer.”

“Besides being great at what he does, Virgil’s success opens up the minds of so many people that it is possible; it can happen to you if you work hard, have determination, focus, and you are driven,” Naomi Campbell, the most prominent black supermodel of the last three decades, told i-D last summer. “It gives hope, a lot of hope.” Benji B agrees. “Momentum is an art form and it’s something that Virgil’s mastered. He’s a beacon of positivity with everything he does. Those two things are irresistible in terms of attracting like-minded people.”

“I am an optimist at heart,” Virgil agrees. “I want to represent as much as what I can and put on the stage what other people can see in the work.” Any heated conversations surrounding his ascent are background noise to him. It helps that his arrival has been good for business: a pop-up in Tokyo that opened earlier this year raked in 30 per cent more in the first 48 hours than Louis Vuitton’s collaboration with Supreme last year, the company’s Chief Executive Officer Michael Burke told WWD.

“In fashion, there’s a tremendous amount of quest for what’s happening next,” he says, pausing to reflect. “But it’s not too mysterious. It’s what’s happening outside the world of fashion. Sometime fashion ignores that and places itself on a pedestal. But times are changing and the future is not that far removed if you look in the right place.”

Credits

Photography Justin French

Styling Carlos Nazario

Hair Mustafa Yanaz at Art + Commerce

Make-up Brittany Whitfield using Glossier

Photography assistance Chad Hilliard

Styling assistance Raymond Gee and Ore Zaccheus

Hair assistance Nastya Miliaeva

Casting Midland Agency

Models Jeffrey, Mayowa, Ahmad Kanu, Jaden Rodriguez and Juantrice Hartfield

All Models wear all clothing Louis Vuitton