As a pop star who is notoriously private, if Solange Knowles has taught us anything over the past five years it’s that music is where she’s willing to offer the world glimpses into her life.

Her last album, 2016’s A Seat at the Table, saw her lay out her pain and pride in what will probably be remembered as one of the most significant records of the early 21st Century. As she explained to i-D during her recent cover interview, the album was “a thesis, and a healing experience”, offered up to the world, specifically black women, as a balm to the weight of the world. It was a record, she has explained, where she felt like she “had so much to say”.

For her new album, however, Solange says she “had so much to feel. Words would have been reductive to what I needed to feel and express. It’s in the sonics for me”. Indeed, When I Get Home, with its loose sonic textures, whimsy and repetition, is more about the frequency and depth of each sound. Solange has said that, as the record’s producer, she would work for 18 hours on specific drum or synth sounds, while the songs were recorded in meandering 15-minute one-takes, after which she would return and edit the songs to find the best few minutes. It’s aural and artistic equivalent of constructing a world of personal and political liberation.

Houston, where she grew up, plays an important part in this world building. In fact, it’s why I’ve travelled from London, at Solange’s behest, to see the places that informed the creation of her latest album and its accompanying film of the same name; the hope being that I can understand and construct a more vibrant and fuller picture of the intention behind her work. After all, where else on the planet can an individual truly create their own universe, complete with personal history, quirks and magic except home? Yet home, in this instance, is far more than just where the heart is. It therefore makes sense that Solange would want to share her vision of Houston — a universe filtered through her mind via sonics and visuals — with others.

Of course, in 72 hours you can’t truly feel the textures and currents of a city. Cities are always mutating, pulsing and contracting with the violence of construction and the torrents of change. Initially, though, the Houston that I see doesn’t feel constructed with the precision that Solange lends to her work. Like many American cities, it’s loaded with the country’s reckless approach to portion control. In parts, like in the hyper-developed Downtown, it feels too big, highways and skyscrapers boxing you in. Others, such as the predominantly African-American Third Ward, located southeast of Downtown, or Montrose, the city’s LGBTQ area, feel in stasis, as if fractured and displaced by time. The old clashes with the new, giving each block a hanging air of melancholy, as if beloved by forgotten. There’s no cohesion, either, each building telling a unique story or perspective.

Ushered on to what can only be described as a party bus, complete with shiny coloured roof and ice bucket, the tour of Solange’s personal Houston is centred on the Third Ward. Driving through the city is eerie. The weather is uncharacteristically cold, but it still doesn’t really account for how quiet the sidewalks are. The people are invisible.

Each location we stop on the tour is significant in some way to Solange, and each one will later play host to a screening of her film. We stop at the church she attended when younger, a large red-brick building with stained-glass windows, the only black-owned bank in Texas, where Solange moved all her money 2016, the Houston Museum of African-American Culture, and the Ensemble Theatre, the oldest and largest African-American theatre in the southwest. It’s where, when she was younger, Solange starred in a production of The Wiz, a musical significant not only because it celebrated urban African-American communities but, like Solange’s world building, imagined an America exemplified by black excellence.

Most impactful, though, were the stops at the hair salon her mother, the inimitable Ms. Tina Lawson, used to own, and the Project Row Houses, where Solange told i-D that she recorded a lot of When I Get Home, a row of picturesque, white wooden “shotgun houses” that act as spaces to enrich and the engage African-American communities of Houston through art, business incubation, residential programs and education. Visiting these locations was overwhelming, because it felt like Solange was opening up the door to her world for us. The barrier between the Knowles family’s public and private life felt thinned, almost translucent. While their artistry is so often seen as bionic and flawless, they are still human beings, and being invited to these places that Solange says were integral to the construction of her identity, the places she calls home, reminded me that she and they are flesh and blood. These weren’t all transcendental places, but they act as puzzle pieces of a personal history — they’re significant because the personal is significant and that gives it gravitas.

“When I really think about it, and what I make my work for, I think about 10 years from now, 20 years from now, 50 years from now. I very rarely think about the present.”

Perhaps all this was an illusion. Or maybe, jetlagged and mildly hungover after too many margaritas, I was feeling overly emotional about being in Houston, craving a connection to a place I knew I would be leaving so soon. However, after we arrive at the SHAPE Community Center (Self-Help for African People through Education) which dates back to the Civil Rights movement, following the screening of When I Get Home, Solange begins her work on the album. It’s like her version of Houston solidified. Like Dorothy being transplanted into Oz, the fantasy becomes a reality.

Whereas A Seat at the Table had an innate urgency to it, musically and lyrically When I Get Home isn’t constructed in the same way. Rather, it’s the film where Solange’s urgency comes to the fore. The world of Houston she creates realigns black culture, black art, black movement and black history in modern America. As Craig Jenkins wrote for Vulture, the sonics of the album and the entirety of the film “is a Carrollian trip down a rabbit hole” where enforced inequality, class distinctions and Jim Crow-era restrictions never existed. “It’s a lucid dream about freedom,” he wrote.

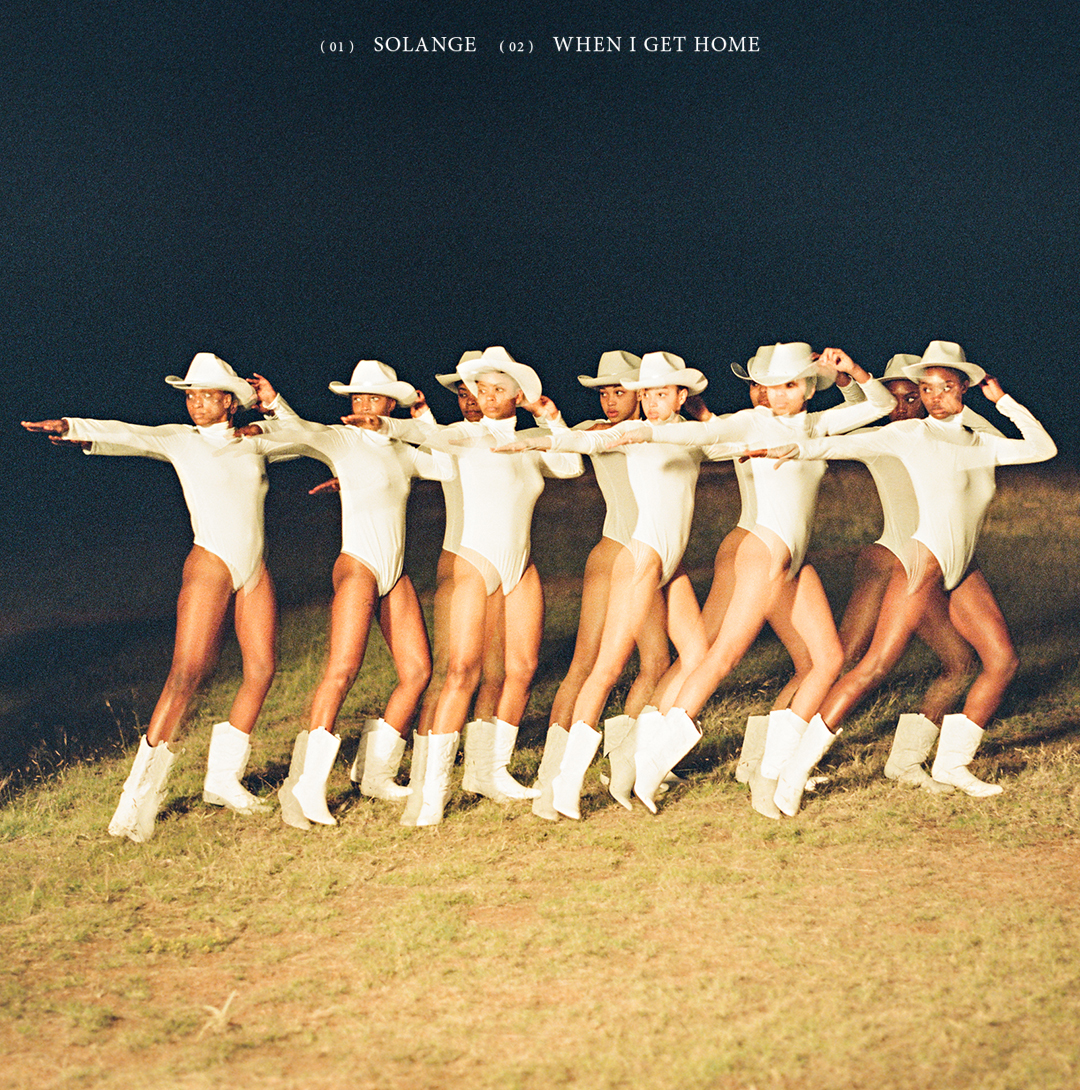

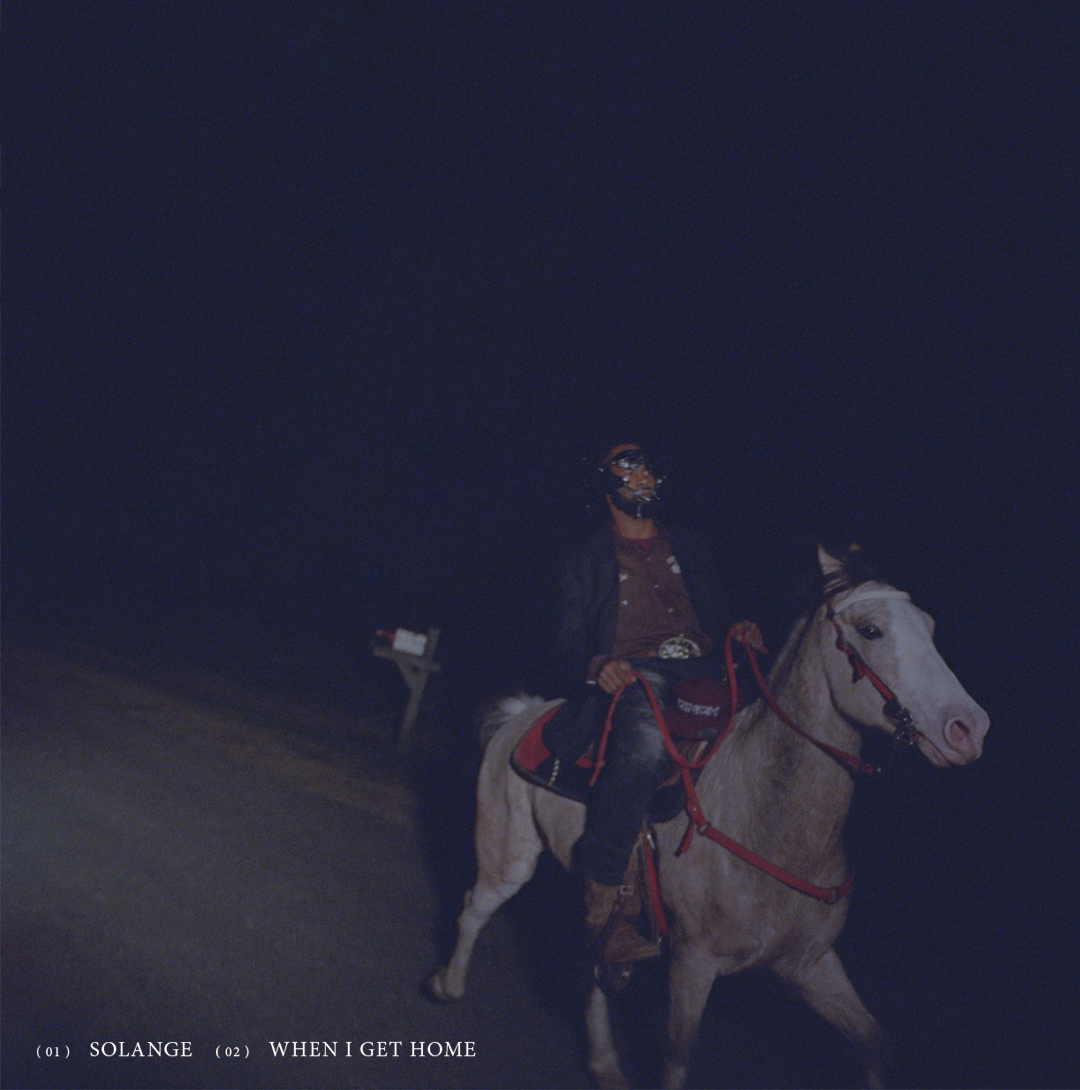

It makes sense, then, that Solange opens the album with the repeated mantra, “I saw things I imagined”. This Houston is one that she has manifested into reality. It’s one where the black cowboys she used to see roaming the street are central to the concept of Americana (they appear repeatedly throughout the film of When I Get Home and some even dropped by the screening in their hats); it’s one where black bodies can create their own worlds through invention, movement and sculpture; and it’s one that she has made mainly for herself to luxuriate in. It’s reclamation as the ultimate homemaking.

During a Q&A and bathed in green light, Solange speaks with intention and, most infectiously, with joy. She admits that she spent the last year just expressing herself, be it artistically or on her Finsta (yes, Solange has a Finsta). She talks about the jazz band she was a part of in high school and about how she revisited that improv style that became the foundation for her work. She describes herself as a “scary bitch” and jokes about not knowing who John Wayne was.

“I think I’m always caught in this place between the past and the future,” she later adds, when asked about reclaiming and centring blackness in her work. “When I really think about it, and what I make my work for, I think about 10 years from now, 20 years from now, 50 years from now. I very rarely think about the present. I think about the way that I discovered Sun-Ra 30 years after he was here and how that work helped me understand myself better. I’m thinking about how at any given time I can google a Kelis image and it can tell me so much about myself and how I see myself. When I think about sculpture and creating sculpture, I’m thinking about the possibility of some young black girl in 20 years needing to reference a black sculptor… and the blessing and privilege that I might come up on their search. So, building worlds and world-making is so much about the future for me because I know how [without] all of those people who left a blueprint for me to exist right now I wouldn’t be anything. That’s my drive.”

Upon after my first listen to When I Get Home I was left confused. The looseness of the record felt at odds with an artist whose previous record felt so direct. But that looseness is like the structural make-up of Houston itself. The album and Houston feel like pieces of a puzzle without any firm shape. Framing the spaces that informed who Solange is as an person, into the world that she has created and reclaimed with When I Get Home, felt like being transported into that world, even if just for a moment. But like she said during the Q&A, sharing that was the whole point: “Any point you truly feel seen you just feel a certain level of joy. That feels so good.”

Sure, getting to travel to Houston is amazing, and being in the same room as Ms. Tina and Solange and her collaborators is an incredible privilege. But the biggest lesson and the greatest gift seems to me that Solange is reminding us that, during a time of great upheaval and darkness, we should look inwards and construct worlds that give us joy, be it by reclaiming our narratives, restructuring our histories or by returning home. As she told i-D, “I learned you can create those spaces; you don’t need anyone else to have your moment.”