I did not expect 2018 to be the year Keira Knightley made me think of Sylvia Plath — it was, I must admit, a year of unexpected turns. Interviewed in The Guardian late last December, Knightley told an anecdote about the fact that as a child, she had believed she would grow up to be a man. “I remember everything about that feeling,” she recalled. “That girls grew into men, and that’s what I was going to be. Maybe it was that the girls were the most powerful in the playground. They were in charge and, obviously, the men were in charge outside. So clearly that’s where I was going. Only, of course it wasn’t.”

“I’ve never wanted a penis,” she added, “apart from to piss up a tree.” Page Six subsequently ran the perfect headline “Keira Knightley says having a penis would be ‘so convenient’.”

Nearly 70 years earlier, in 1950, Plath wrote more or less the same thing in her journal: “I dislike being a girl, because as such I have come to realise that I cannot be a man.” Needless to say, the parallel caught my attention — coupled with an essay written about childbirth for last year’s book Feminists Don’t Wear Pink, which opens with the three immortal and gynaecological words: “my vagina split”, I had to wonder where this freaky, feminist incarnation of Keira Knightley had been for the last two decades of her fame. As it turns out, there had been traces of her present more or less since her big “comeback” year in 2010, when she returned to film after taking a year off to recover from media-induced, paparazzi-stoked PTSD.

She was there in 2012, in Vogue, saying that she “remember[ed] doing interviews, and people would ask, as if it was a joke, ‘So you mean you are a feminist?’ As though feminism couldn’t be discussed unless we were making fun of it,” and in The Guardian in 2014 suggesting that Bend it like Beckham “managed to be amazingly optimistic without making you feel you’ve been raped by sugar.” “I think, personally, the whole way that we’re viewing women and the way that we build them up and pick them apart is really frightening,” she told Harper’s Bazaar in an interview in 2017. “Particularly now, being the mother of a girl, and you think, ‘How do you navigate that?’ And I don’t have the answer.”

Looking for an answer as to why the actress was disliked enough to have developed Goddamned PTSD from ill-treatment by the media and the general public is not so straightforward, either. Google “Keira Knightley hate”, and after first suggesting that perhaps you meant to type “Keira Knightley hat”, the engine throws up: “What is it about Keira Knightley that gets people all riled up,” “Why does Keira Knightley arouse such loathing,” and the alarmingly presumptuous “Why we hate Keira Knightley” as the first three hits. (Writing this piece, one possibly-legitimate reason occurs to me: that remembering to spell it “Keira” and not “Kiera,” in spite of the way it’s said, is practically impossible).

To say with confidence that “we” hated Keira Knightley is inaccurate, the same way it was not entirely accurate to say that “we” disliked Anne Hathaway in 2013. It makes more sense to say that both actresses, wide-mouthed, overeager and extremely beautiful in a way somehow utterly divorced from sex, triggered some mass dislike in women desperate not to be seen as too try-hard. Being earnest or enthusiastic, like being “hysterical” or “crazy”, is un-chill, a cardinal sin for women who love men, and who want to be loved by men. Internalised misogyny is, to no sane woman’s surprise, a helluva drug.

I thought, and still do think, that Knightley’s earliest performances did not bring much to the screen other than her perfect good looks. I had no idea, however, that she felt the same way: several interviews make reference to her terror that by the mid-to-late-noughties, her outsized fame had outstripped her fledgling talent, and her year off also meant time to learn to be more adroit. “I was aware that I didn’t know what I was doing, you know?” she admitted to The Hollywood Reporter last October. “I didn’t know my trade, I didn’t know my craft. I knew that there was something that worked sometimes, but I didn’t know how to capture that.”

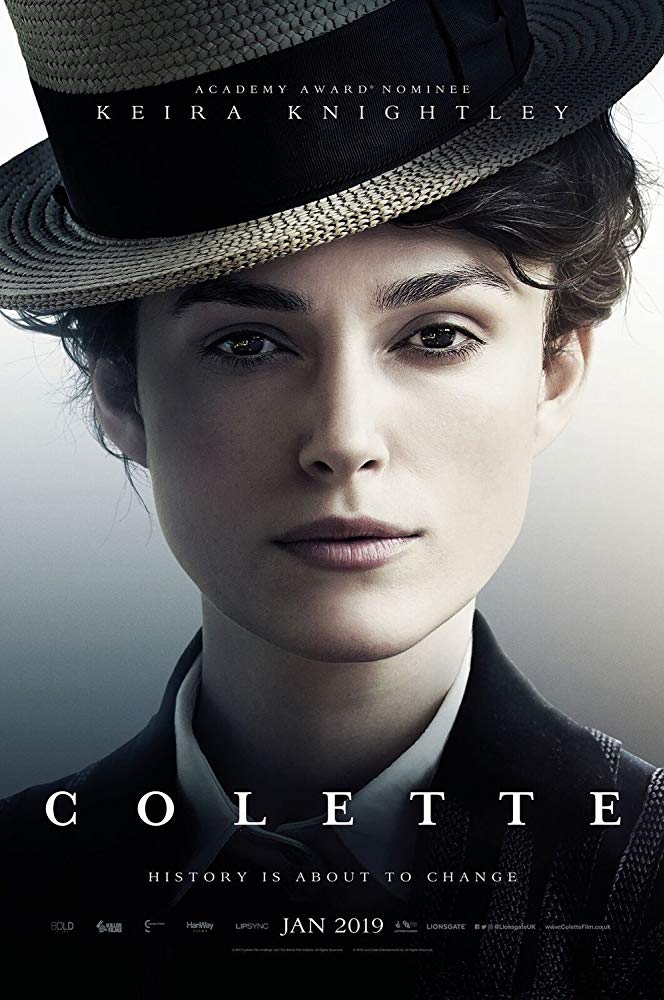

This month, Colette, a lush, queer biopic of the lush, queer French writer starring Knightley in the title role gets a UK release — playing the author like a proper, witty head girl with a naughty Sapphic streak, she is markedly more confident than in a number of her past roles. “Wash [Westmoreland, the director] was trying to get this made for 17 years,” she assured The Irish Times, “so this was in no way ‘oh there’s a female movement so let’s make a movie to capitalise on it.’ Obviously, it’s a film about a woman stepping out from the shadow of a man and finding her own voice, and her own way to live. The fact that it was made when it was and finally got financing is because feminist issues are suddenly more culturally acceptable.”

It is more culturally acceptable now, too, for actresses to talk about their politics, their split vaginas, and their personal opinions on whether it might be easier to piss as the possessor of a penis, even in big-ticket broadsheet interviews. Feminine frankness is no longer off-putting, but en vogue; this, and not movies, may still prove to be Keira Knightley’s strongest suit. “I don’t want to flirt and mother [men], flirt and mother, flirt and mother,” Knightley hisses in that childbirth essay, which is called The Weaker Sex. “I don’t want to flirt with you because I don’t want to fuck you, and I don’t want to mother you because I am not your mother.”

Reproduced in last year’s Guardian profile, this quote in particular appears — at least from Twitter — to have struck a chord. I saw a wave of women tweeting: I had no idea I loved Keira Knightley. I hope that she reads those tweets as diligently as she used to read her bad reviews. I hope she never shuts up, never feels the need to “flirt or mother” anyone again.