This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Superstar Issue, no. 354, Winter 2018

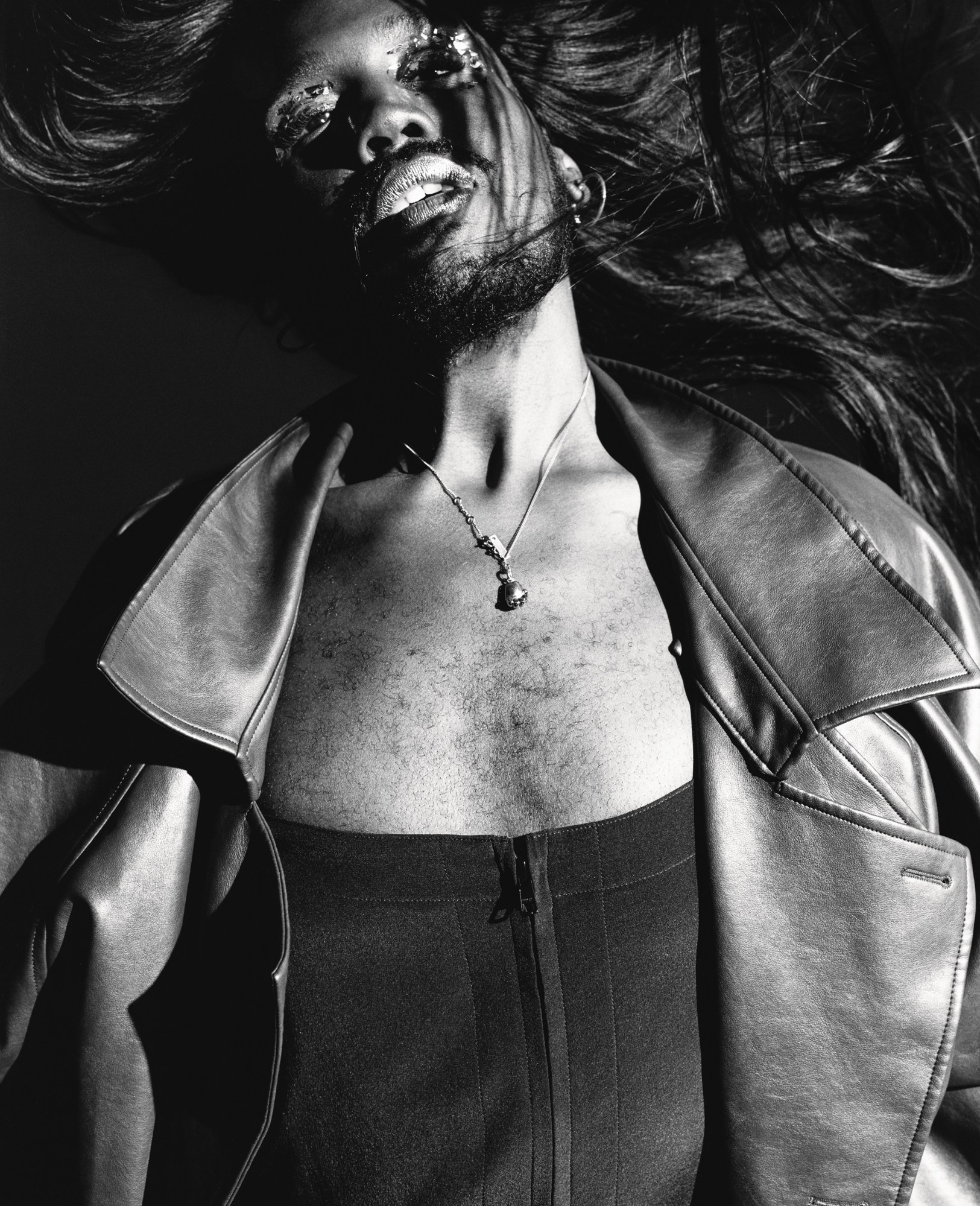

Kiddy Smile has had an insane few months. His fame came slowly, then all at once. Over many years, he tried to make it as a dancer and had some success, but after being rejected for Madonna’s tour, he realised that being big, black and queer meant the industry would never fully accept him. He turned to music and over time explored different genres before settling on house. In 2016, he dropped his video For Let a Bitch Know. In the video Kiddy and his friends from the Parisian ballroom scene vogue and burn out cars in the banlieues (“the projects”, as Kiddy calls them) where he grew up. French media began to pay attention. Kiddy appeared on Le Gros Journal and other national TV programmes.

Then suddenly, in the summer of this year, Kiddy got a call that would make him even more famous. French President Macron invited him to his official residence, the Élysée Palace, to DJ. Kiddy brought his black, queer friends to vogue on the palace steps, while he wore a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase “Fils d’immigré, noir et pédé” (Son of immigrants, black and gay). Jaws around France, and the world, dropped. Kiddy exploded. Marine Le Pen subtweeted him, he ended up in just about every French publication there is, on French television, and profiled in the Guardian and the New York Times.

Sitting today in a cafe in Paris’ 20th arrondissement, he stirs a lukewarm cappuccino. His debut album, One Trick Pony, has been released, but not that much has changed. “I’m still broke. I’m still in an apartment that’s too small for me,” he jokes. “I do get some free clothes though, I’m not gonna lie.” It’s the middle of Paris Fashion Week, and Maison Margiela have invited him to their show. “They gave me a coat to wear,” he says, “but it was too much. So I just wore a black T-shirt.”

Kiddy’s air of serene, unbothered certitude is a powerful relaxant. You feel calmed by his presence. Just as coolly as he turns down revered designers’ outfit suggestions, he unpicks the media’s treatment of him since his rise to prominence. “People were so happy to be able to portray the projects as homophobic,” he says of coverage of his Let A Bitch Know video. “I felt like people were fantasising a lot about the banlieues. There’s just as much homophobia in the church or in politics as there is in the suburbs.”

“You have to understand that, in France, homosexuality was never represented by black men on TV or in other media. I waited 18 years to meet another person that looked like me and was also openly gay. That’s why I wanted to do that video – so there is testimony to being openly gay in the projects, so young people don’t feel alone like I did.”

Representation is deeply important to Kiddy. He comes back to it again and again, relating every high-profile decision he’s made back to this one grounding principle. “When I went to the Élysée I was immediately called out because the government is still oppressing gay people. All these white people were like, ‘You shouldn’t go there, we don’t have PMA, etc.’” (PMA refers to medically assisted procreation, which is only legally available to straight couples in France).

He leans in close. “I am more concerned with people who look like me not seeing ourselves in places like that, feeling the way I felt. I want to be an example, that you can be black and gay and get an invitation to the Élysée. They said ‘You going over there is gonna be used as a PR tool, you’re gonna be pinkwashed’. I’m telling you that I need my people represented? That this is a big step for us and this is what’s more important for you?”

This is the just tip of the iceberg. The world seized upon his image as a lightning rod for conversations around representation, appropriation and reclaiming black queerness. So often though, these conversations are conducted by white people imposing their own political meanings. “It’s a very colonialist way of thinking. Everyone’s gonna project onto me, my black body.” He shakes his head.

But that’s not to say Kiddy isn’t also very concerned with issues like appropriation and reclamation. We talk about the legacy of house music, how it was created by black gay men like Frankie Knuckles in the 70s. If you Google ‘house music’ in 2018 you get David Guetta, Avicii, Swedish House Mafia. They’re all – “straight white men,” Kiddy interrupts. “It’s been stolen. Whitewashed. Completely.” He says with a hard edge to his voice. Then he softens. “What can I do? People don’t even know house is black. I didn’t even know. That’s why I started doing hip-hop, because I thought that was the legacy my people created for me. When I started digging into house, I realised French touch is inspired by Chicago house music, which is black and gay. So why was it presented to me as something white and straight? The problem is, I don’t think we can truly reclaim something until we break the system.”

Some might argue that we’re already on the way. Artists like Kiddy, and TV shows like Pose – which is about queer people of colour in the 80s ballroom scene in New York – have prompted many to celebrate what seems like whiteness’ waning stranglehold on culture, its loosening grip on black tropes like voguing that were historically stolen. Kiddy featured the voices of two ballroom icons from Pose’s first season on his album but raises an eyebrow. “But who’s on top of that? I don’t wanna say anything negative about it but it’s not completely reclaimed when it’s still Ryan Murphy, a white guy, at the top. It could have been Lee Daniels. Yet again, who’s celebrated? Who’s gonna be remembered for that show in ten years? That’s why I don’t think you can reclaim things until you break the system. People just let you have them for a moment so you shut up,” he says.

“In the end, it’s still progress,” Kiddy continues, more brightly, and starts to talk about his appearance on another French TV show the previous week when the presenter said to him: “I like your record but the media are only being nice to you because you’re black and gay. I don’t understand why you keep bragging about it – nowadays it’s easier to be the son of an immigrant, black and gay, than it is to be a white straight man.” Things like this are exhausting for Kiddy. “A lot of people were annoyed that I was in the New York Times, they don’t think I deserve it. So they’re looking for explanations for why I was there,” he says. But he doesn’t let these things kill his spirit. Kiddy’s aware of how important what he’s doing is. “You have to be there. In order to get your point across, you have to sit at the table and let your voice be heard. If you’re not there, you can’t.”

“I’m lucky. Not everybody gets to do this,” he says gazing out the window at the couples chatting and smoking outside. “But if the man of my dreams arrived and asked me to drop everything, buy a house and have kids, I think I would. I’m doing all the things that I’ve dreamed of, and it’s cool that I get to share it with my friends, but” – he exhales with a big grin – “I need someone to rub my feet.”

Credits

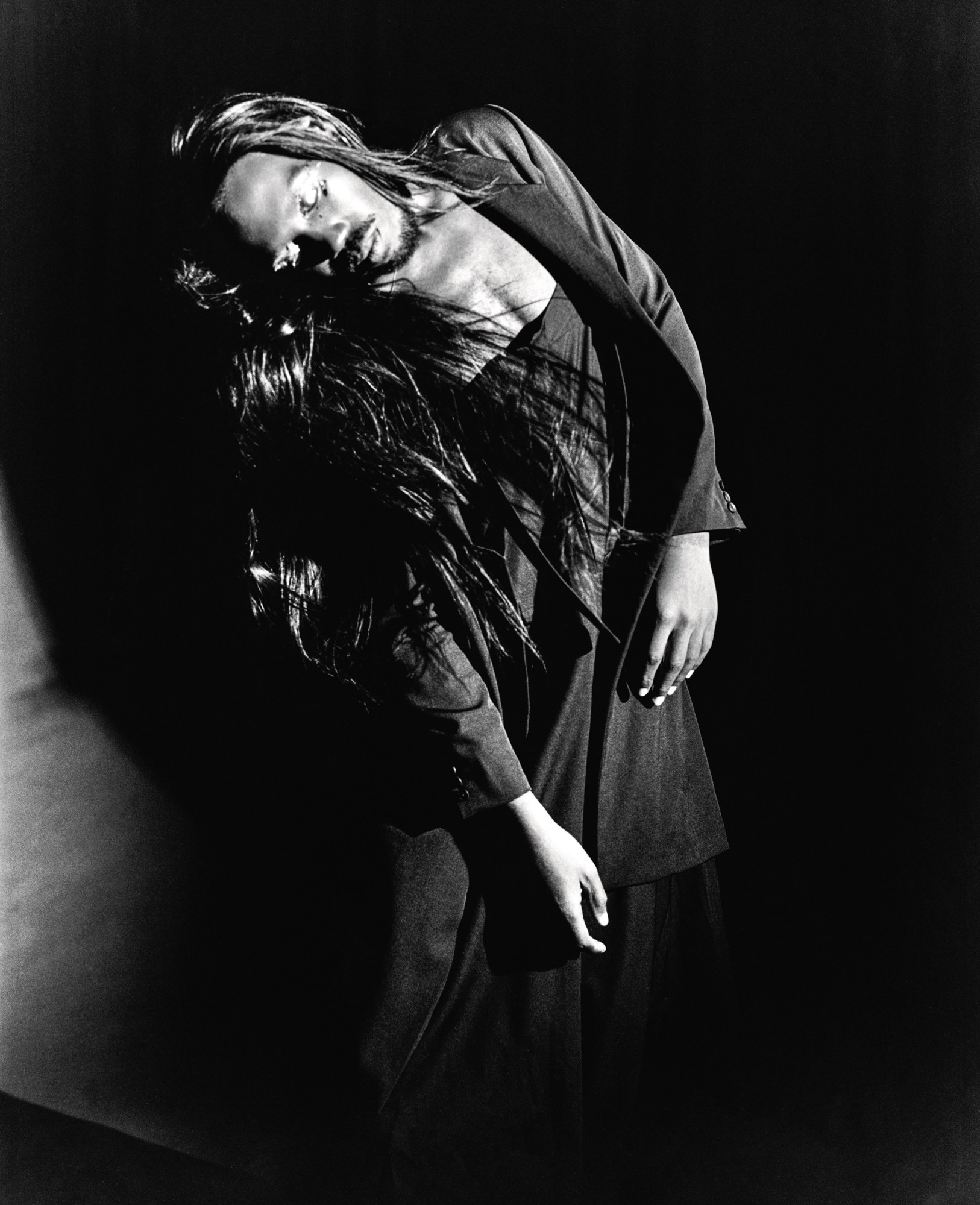

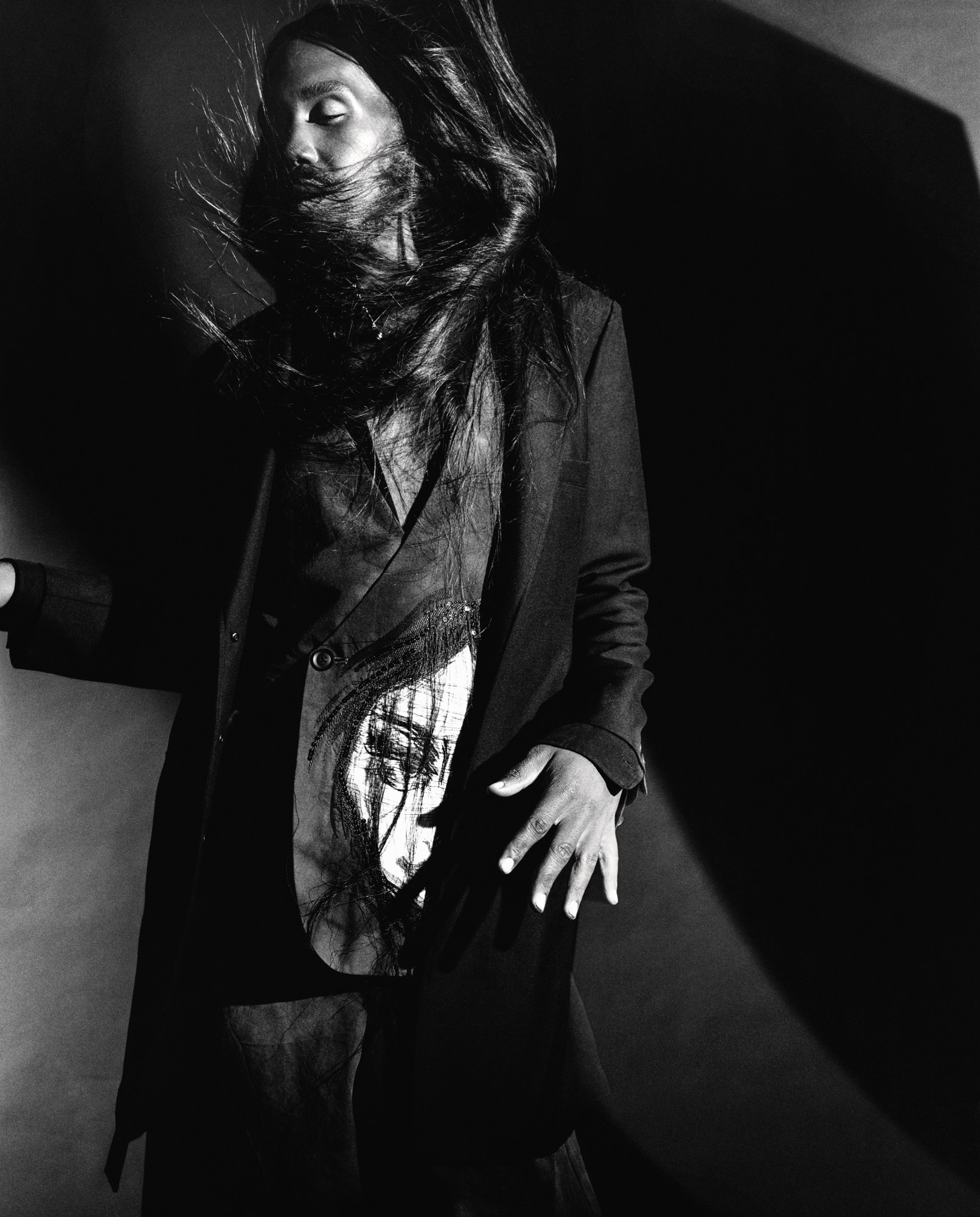

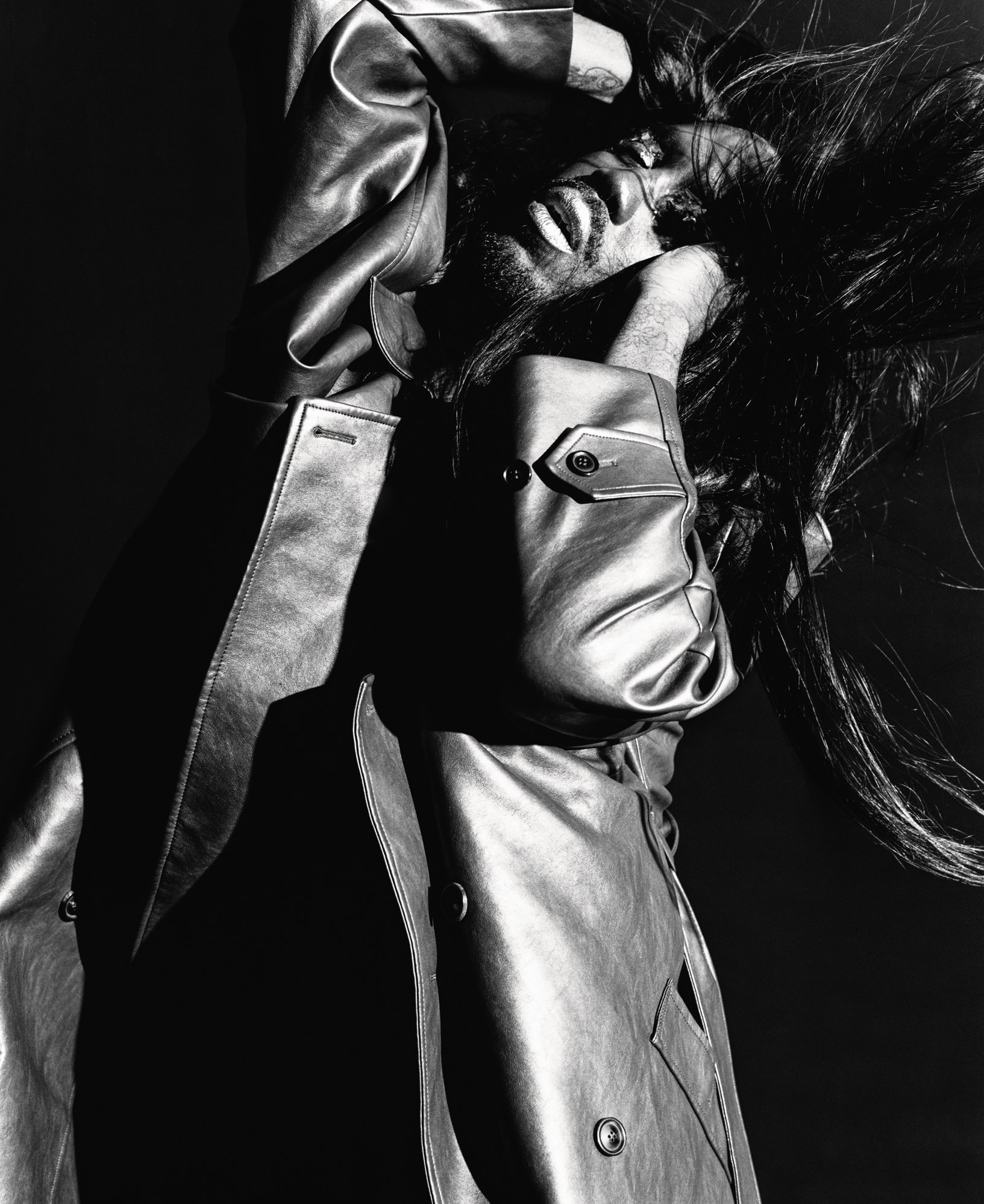

Photography Oliver Hadlee Pearch

Styling Carlos Nazario

Hair Cyndia Harvey at Streeters. Make-up Susie Sobol at Julian Watson Agency. Photography assistance Mitchell Stafford and Adrien Thibauld. Styling assistance Alain Luca. Make-up assistance Shannon Rodriguez. Production Vera at Kitten. Special thanks to Ibrahim Tarouhit.