This article originally appeared on i-D FR

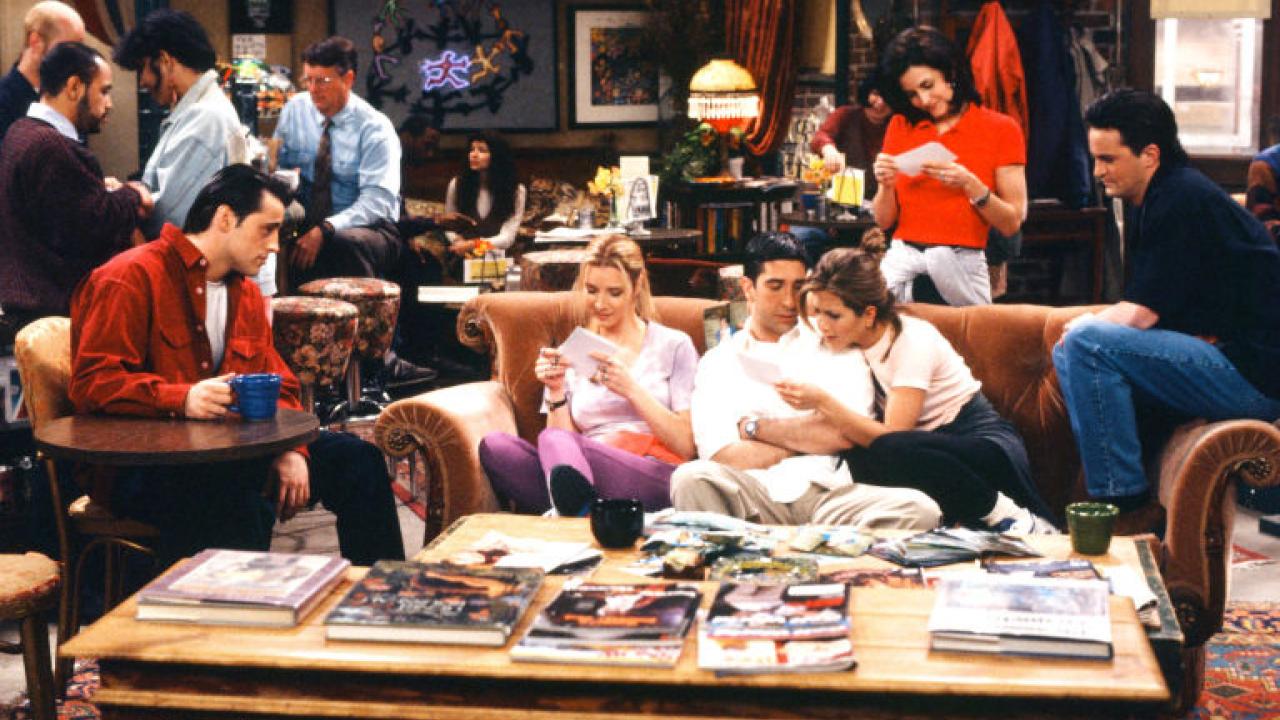

Sometimes the shows we grew up watching are safe havens: we keep coming back to them time and time again, to experience unchanged levels of comfort, as well as addiction. Friends is one of these evergreen TV shows, with characters and sets that remain familiar to the viewer even two decades past their inception. The purple walls of Monica’s apartment, Central Perk’s mugs and armchairs, or Chandler and Joey’s foosball table… each of them is now a mythical piece of scenography, all designed by a man named John Shaffner.

Besides his work on Friends, Shaffner has also served as Production Designer on shows like Two and a Half Men, The Big Bang Theory, and Roseanne. We got in touch with him for a chat.

What did you do before becoming a Production Designer?

I followed a very normal route: I studied design and stage work at the university of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After that, I worked in the theatre business in Seattle, and later in Manhattan for a few years. I was pretty lucky at this stage: I was offered a chance to work the sets for the David Copperfield shows and to hone my skills on The Golden Girls — the sofa was one of my ideas. Then I moved to Los Angeles. It was easier to find work over there. This was TV’s golden age – there were so many talk shows, award shows, and sitcoms being produced. Even if I didn’t really want to leave New York, it was clear to me deep-down that I belonged in the very heart of the industry, which is Hollywood.

What’s the best thing about being a set designer?

I love being the first guy to read a script – sometimes even before the director. But of course, there’s much more to my job than that. Working on sets requires proper teamwork, and when it comes to TV series or films we’re in constant communication with the entire production team.

For Friends, I got to come up with everything: Monica and Rachel’s flat, the floor it’s on, the type of windows it should have, the color of the walls, etc. To be able to envision all of this, one needs to get familiar with the tone of the series, with its humor, and with the directors’ ambitions. The simple way to define my job would be to say that I breathe life into a project. I create a frame, an environment. But then of course, I’m not alone in this: Nowadays, I’m surrounded by an entire team who bring my ideas into shape.

Do you consider Friends your masterpiece?

I’m very fond of all of my projects, but Friends undoubtedly brought me the most recognition. I was involved in it since the pilot – when the show was still called Friends Like Us. I remember meeting Matt LeBlanc and thinking: “This young man doesn’t know that his life is about to change forever!” As we all know, that was a safe assumption. Personally, I have to say that my time in New York was a great inspiration. Monica’s and Rachel’s place is largely based on the one I had in Manhattan, except that my bathroom was just outside the bedroom.

Did you feel that the set should project an image of the New York of that era?

Of course! The series’ directors, David Crane and Marta Saufman, were living in New York throughout the late 1970s, and I think we all shared a rather precise vision of the way we wished to portray the city. We therefore came up with a few tricks to present an image of New York that was both cool and authentic: since we had to set the scene in a rather cheap apartment, we chose to have it on the 6th floor of a building that has no elevator. Similarly, we had to have six characters appearing in every episode, which implied that we needed a place for them to meet. That’s why Monica’s place and the Central Perk became vital in the Friends imagery.

Other spaces, such as the landing between the two apartments, also played a crucial role throughout the series.

Yes, and the building’s hallway is a good example of such a space. At first, the directors didn’t regard it as a fully-fledged acting space. I pointed out that they should seriously consider using it. That’s the beauty of my job: I need to be able to anticipate what could be useful to both directors and screenwriters.

For The Big Bang Theory, for example, they didn’t want Sheldon’s and Leonard’s building to have an elevator. The actors were supposed to reach their apartments by going up a stairway. I insisted that there should be an elevator – for the set’s ergonomics but also because it added a comical element to the situation. The fact that the elevator is out of order over the course of twelve seasons offers an extra plot line.

How long did you spend on imagining and conceiving the sets for Friends?

We were given six weeks to get everything ready and approved. On average, we’re given somewhere around two months, so for this show we had to work pretty quickly. To get it done, we used to pick up the furniture that Upper East Siders were throwing out onto the streets. We needed the set to be authentic and unique. Hence the purple walls in Monica’s flat, for instance. It’s a bold move if you think about it, but the viewer understands where they are instantly. Even today, if you turn on your TV, you’ll know straight away if you’re watching Friends.

Was your experience working on Big Bang Theory and Roseanne any different?

Every sitcom is different. The game is to conceive a realistic environment for fictional characters, a context in which they could evolve if they were real. For Two and a Half Men, for example, the idea came very quickly to have all of these lovely people living by the sea in Malibu. This enabled me to put together a peaceful fantasy, where life is sweet and where Charlie Harper’s little brother could seek refuge with his ten-year-old son.

With Roseanne, it was a whole different story. The show lasted for more than 20 years. So we had to create a set that could stick with the show’s aesthetic, while allowing it to remain in line with our times. Which is why the sofa and the wallpaper had to change.

Many of us would have loved to live in Monica’s and Rachel’s apartment…

Yes, and that’s what so beautiful about my line of work. But it should be noted that the multi camera setup did a great deal to introduce a certain proximity to the viewer – a feeling of familiarity.