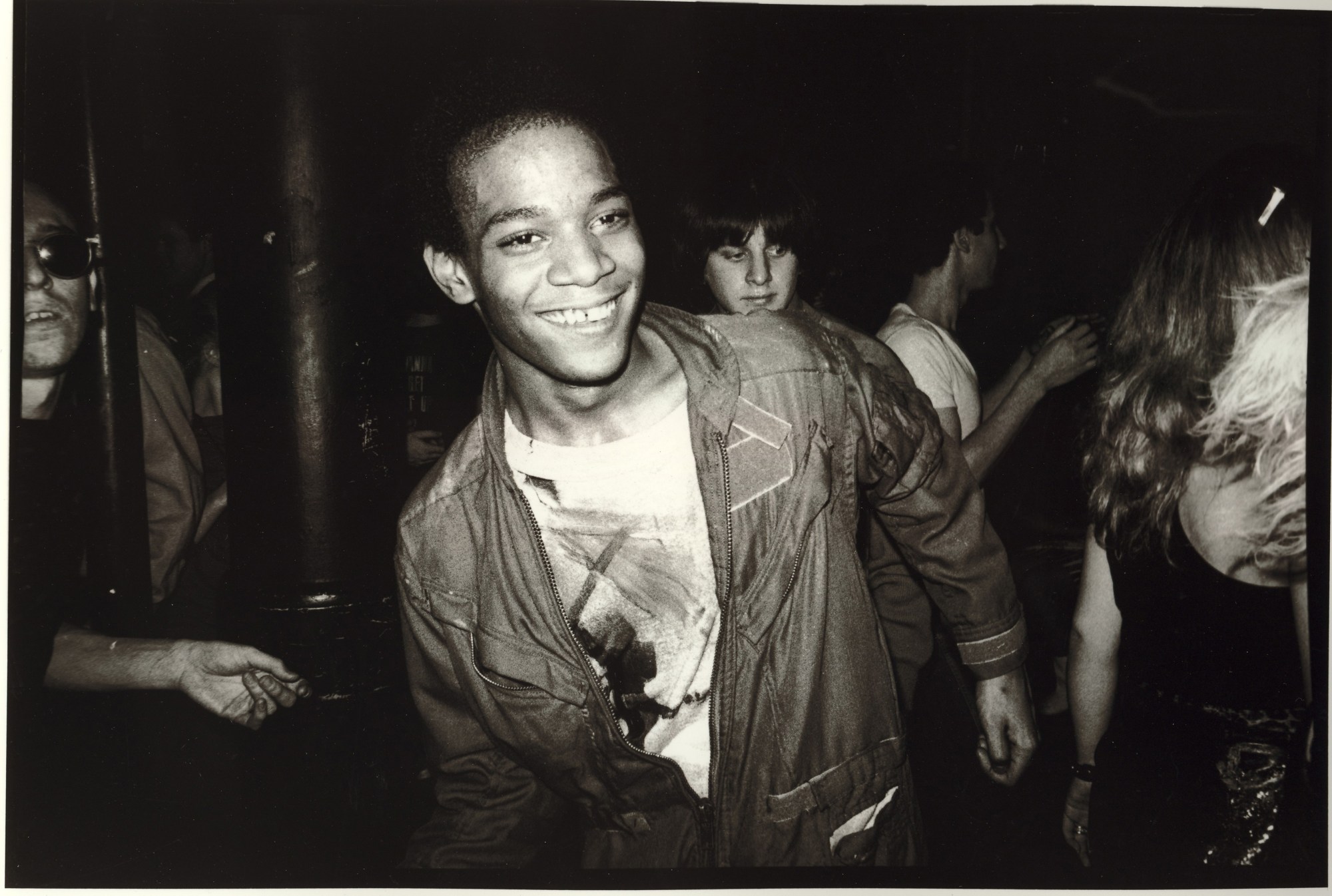

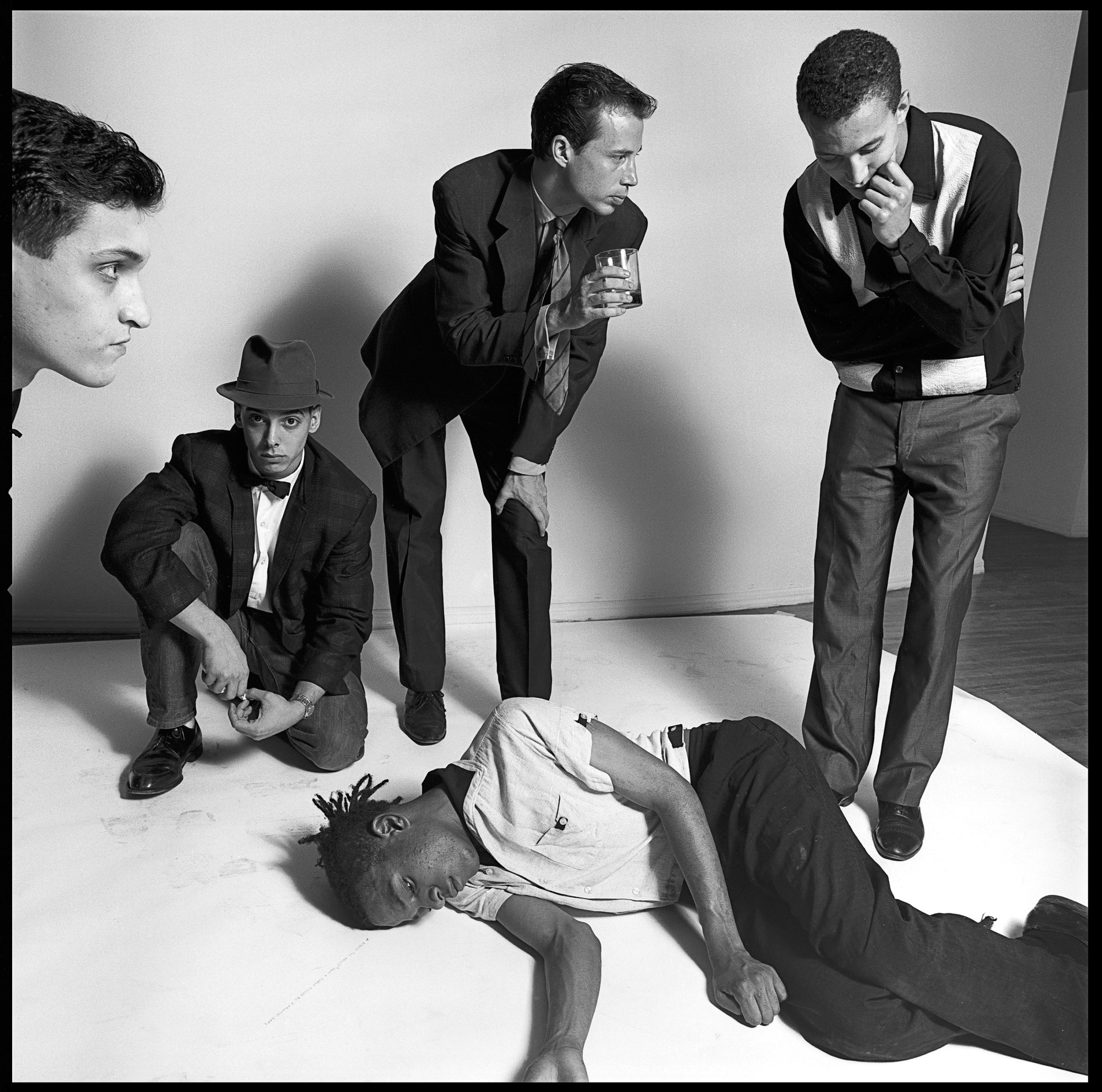

Many shows have highlighted Jean-Michel Basquiat as a major 20th-century artist, his importance vastly transcending his nine short years of exuberant output. Basquiat Soundtracks, on view through July 30th at the Cité de la Musique in Paris, stretches his legacy further. It explores the New York scene in which he was enmeshed (including the many cool weirdos who frequented the Mudd Club), while also underlining his aural aptitudes (producing and arranging Rammellzee and K-Rob’s track Beat Bop; dabbling briefly in a John Cage-inspired band, Gray). The exhibition posits that Basquiat painted musically, and that music can be a lens through which to situate him as a creative figure.

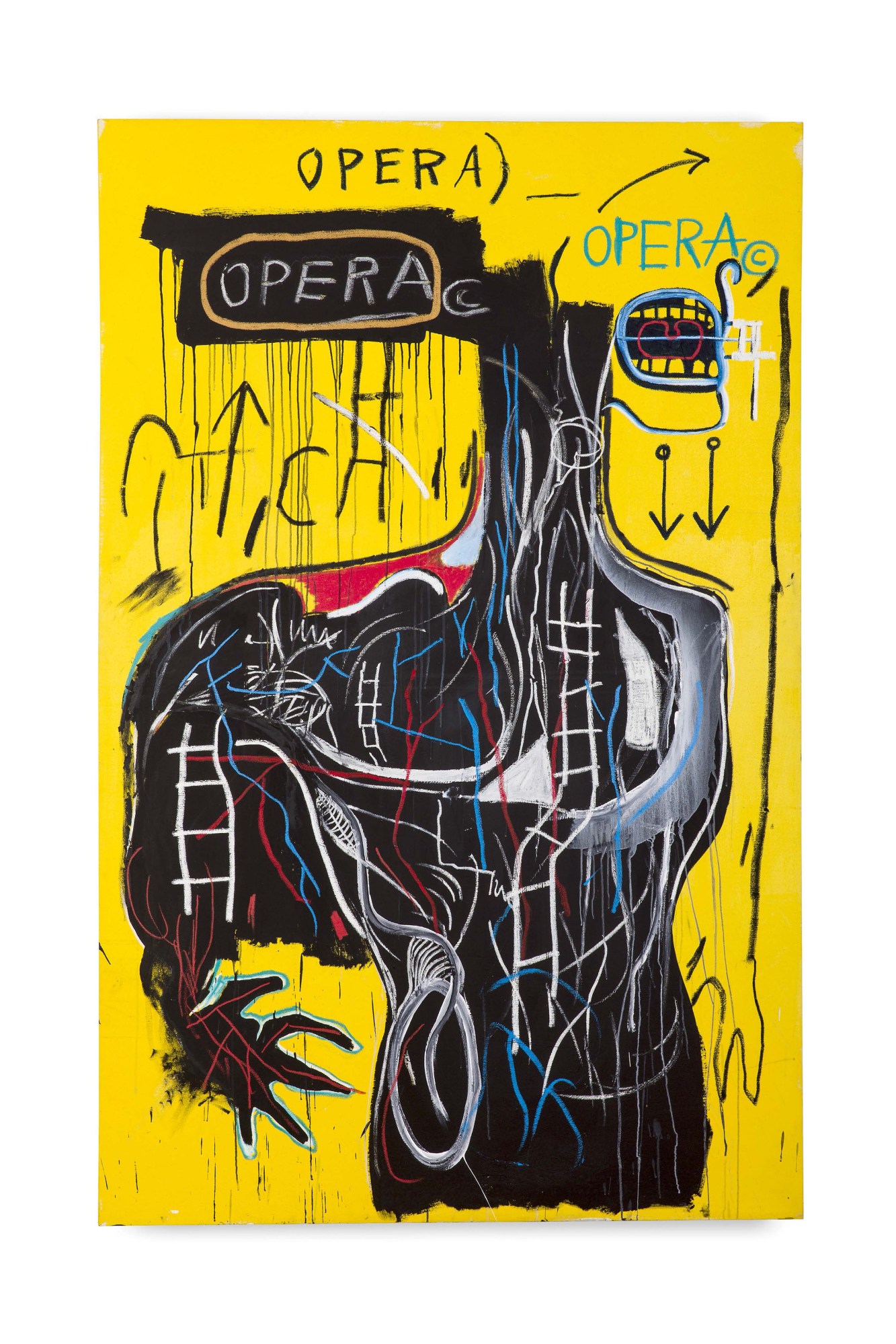

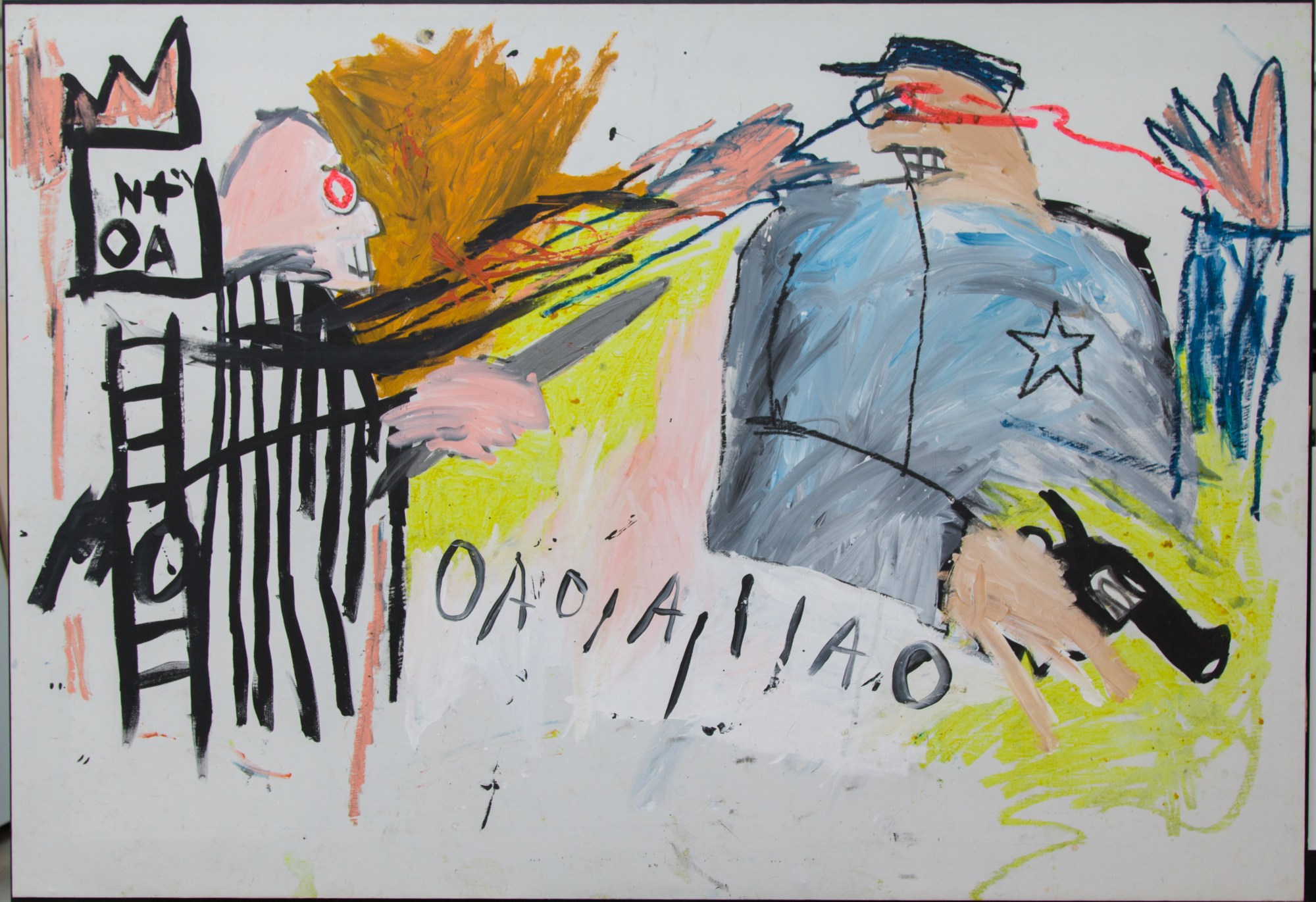

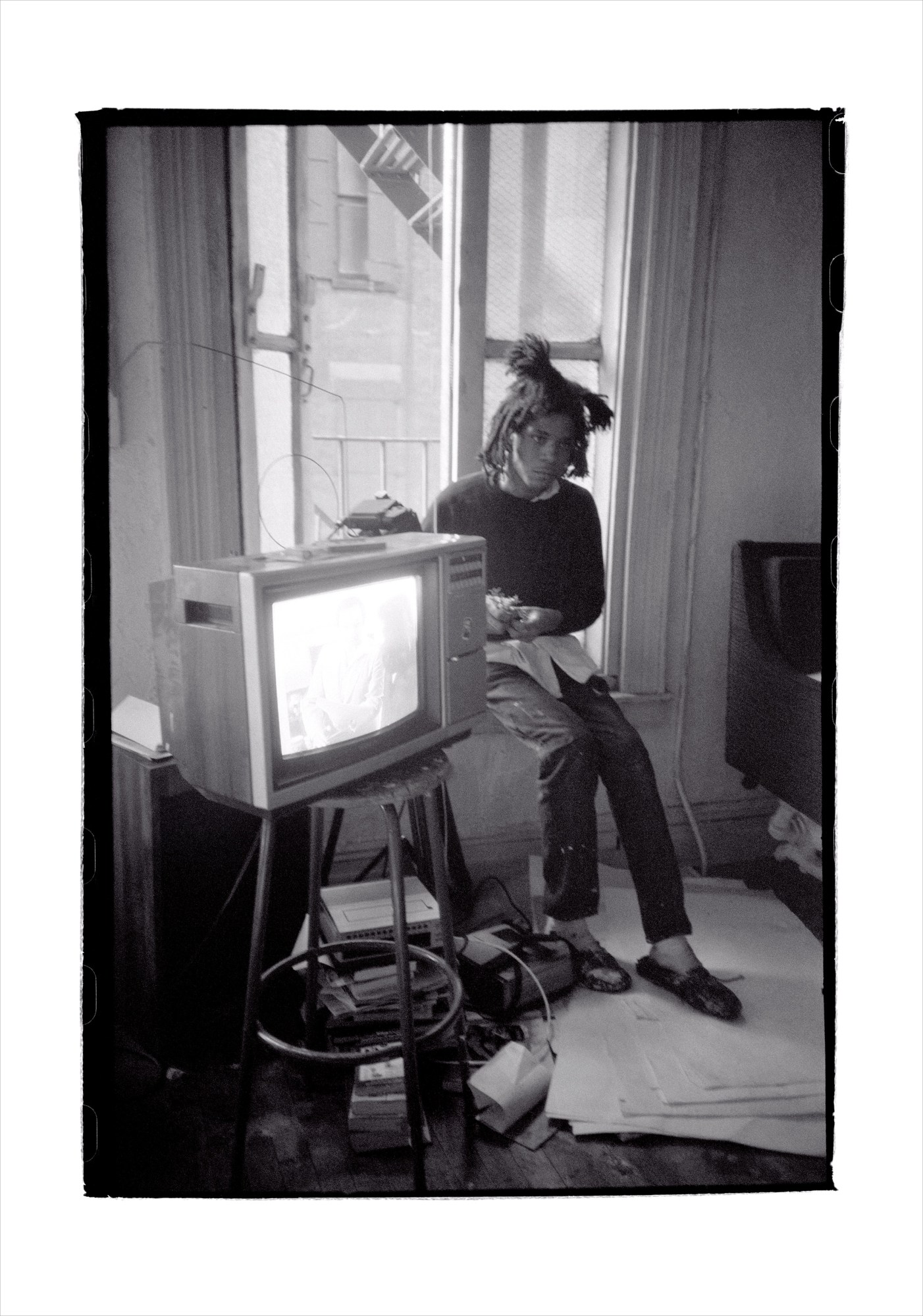

The New York that Basquiat lived in was destitute and quieted by white flight: the charged consciousness of the city seeped out through graffiti, DJing, and breakdancing. “He was seeing all those outcasts who were bringing in their own music, creating their own identities, not afraid of anybody… To him, that had appeal,” remarks Vincent Bessières, one-third of the curation team behind the exhibition. His references, musically, were not simply no wave and hip hop, but Maria Callas, Beethoven, and Ravel. In the movie Downtown 81, when Basquiat’s character leaves the hospital in the film’s opening, the only personal item he retrieves is a clarinet. Out on the streets, when a cab honks at him, he plays the clarinet back in response, as if sound — not language — is the means of communing amidst urban turmoil. Even his visual works often lean on comic book-like onomatopoeia, like figures yelling the word OPERA, or abstracted representations of Dizzy Gillespie.

Vincent explains how musical rhythm functions “on the level of composing the works” for Basquiat, from the canvas to city walls to paper sketches. Vincent talked to different people who spent time in Basquiat’s studio, pored over books and documentaries, and studied the paintings and drawings. From there, the team built out a compilation of songs, musicians and albums, supplemented by the sounds of New York, like a subway passing, or a police car siren wailing, or even a spray can hissing. For the exhibition, the audio data was fed into AI software. The sophisticated program, Vincent says, “is able to analyze songs and find connections in terms of BPM and tonality and texture… It’s about creating a sonic landscape, which moves and creates an atmosphere.” Celebrated sound designer Nicolas Becker — behind the film The Sound of Metal and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s current film in production — consulted on the exhibition to further elevate the quality.

The show is sectioned into two, and subdivided into immersive thematic clusters. The first half focuses on late 70s and early 80s downtown, featuring postcards Basquiat would sell on the street, band flyers he designed for friends, videos of live no wave performances and Polaroids taken by French photographer and designer Maripol. The second half of the exhibition tries to deconstruct the way Basquiat represented music visually in his paintings. Vincent says, “I didn’t want the exhibition to be a white cube with works shown one next to one another. That’s not what music is about — especially for no wave music, punk music, post-punk music or hip hop. I didn’t want it to look too regular… we made a scenography that is more like a labyrinth, with rooms that you can navigate different ways.”

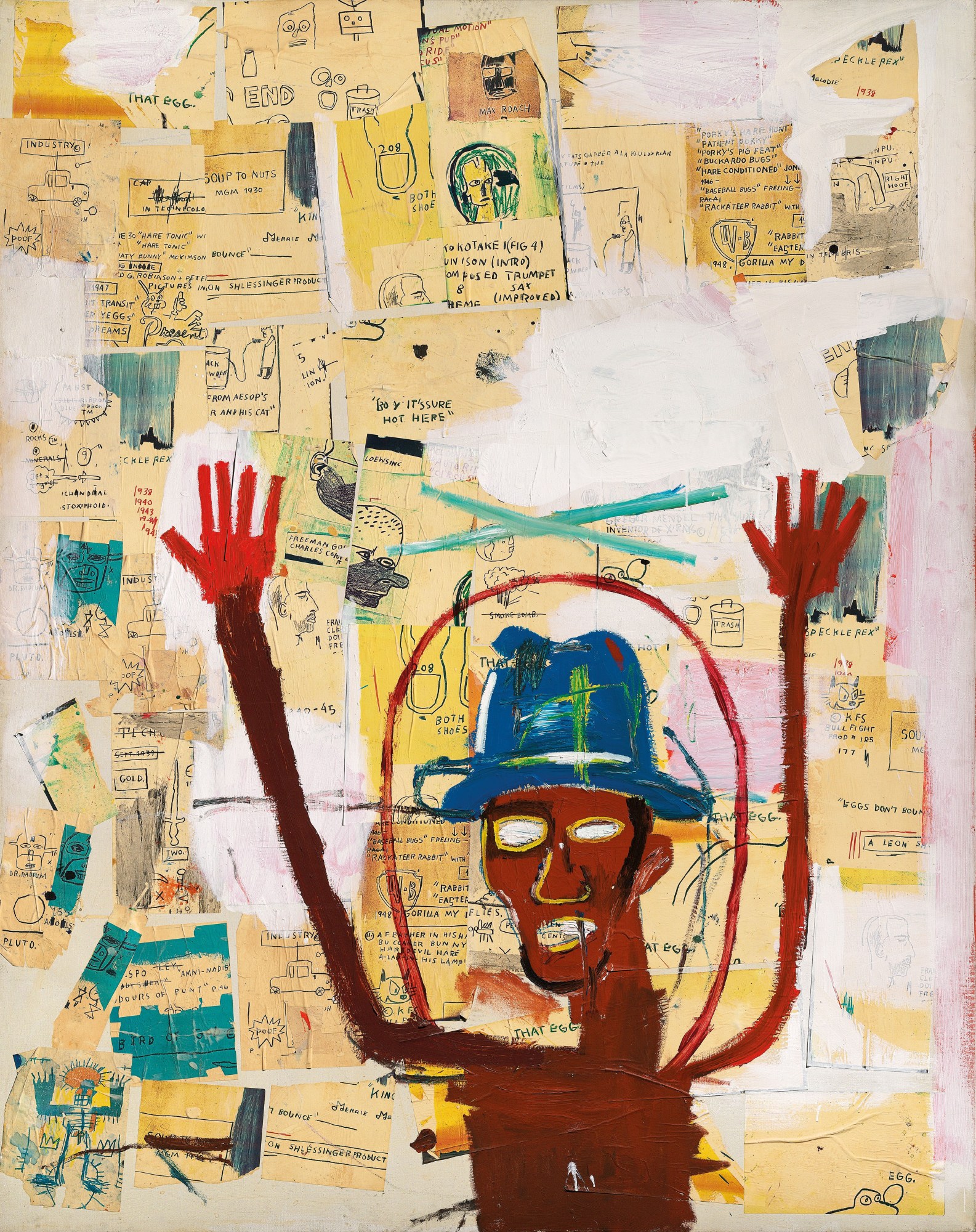

From 1982, Basquiat started using Xerox to replicate his own drawings and collages, sprinkling them in his larger works. “It’s kind of like he’s sampling himself, like a hip hop producer would,” Vincent notes. The print of a men’s shoe (worn by Erica Bell, an African-American dancer who collaborated with Madonna at the early stage of her career) is used in one work, while a dozen Xeroxes are glued to look like toe-tapping or dancing in another. “You can think about it as someone who has a melody in mind,” Vincent points out. “Like: How do I use that melody and what can I do with the same series of chords?”

A different musically-inflected component of Basquiat’s work is connected to Black history and diaspora. These themes not only shaped his identity (he was half-Haitian, half-Puerto Rican), but “some of his work is really trying to materialize visually a history that couldn’t be written, because people were cut out of their languages and cut out of their religions… It’s a history that will forever be incomplete,” Vincent says. Basquiat was fascinated by Louisiana and Zydeco: a hybrid music resulting from people of African descent bumping up against French-speaking Canadians deported by the British, ultimately mixing French songs and African rhythms played on the accordion in a swamp bayou vibe.

The Flash of the Spirit, written in 1983 by prominent art historian and professor Robert Farris Thompson, was a very influential work to Basquiat. Thompson’s book is about the connections in art that thread through territories of West Africa, Central Africa, Brazil, the Caribbean, and Harlem that survived diaspora through continuities and shared heritage. Basquiat read this book and asked the scholar to write a foreword for one of his exhibitions. He also gave him a painting, which was sold recently, themed around Zydeco.

Basquiat has been somewhat of a victim of his own success, and the art market narrative has stripped him from the club culture and underground milieux he was an integral part of. He would surely honk his clarinet in refutation at anything that minimized the spontaneity and grit of the scenes that shaped him. Basquiat prized street art over galleries, urgency over contemplation, scrappy experimentation over the polish of the establishment.

Basquiat Soundtracks is on view at Philharmonie de Paris through July 30th.

Credits

Images courtesy of Philharmonie de Paris.