Lisetta Carmi worked as a photographer for eighteen years, from 1960 to 1978. She chronicled—and humanized—marginalized communities amid the late mid-20th century in her native Italy and beyond, willfully ignoring sociopolitical taboos. Her photos were incredibly prescient: today, as the cultural contemporary conversation around gender identity grows more complex, her singular series I travestiti packs an even more remarkable punch. The raw honesty of her gaze, which has been equated with the spirit of photographers like Christer Strömholm and Nan Goldin, is currently on view at Museo di Roma in Trastevere in Rome through March 2019, spanning over 150 images from her body of work, many previously unpublished.

Carmi was born in 1924 in Genoa to a cultured Jewish family; today, at the age of 94, she is still vibrant and sharp. Before her chapter as a photographer, she was a successful concert pianist and teacher; later, she became a disciple of the guru Babaji Mahavatar Himalaya, whom she met in Jaipur, and who inspired her to found an ashram in Puglia. Although her photographic output went overlooked for several decades, it has experienced a late-in-life revival: she was the subject of a 2010 film, which screened at the 67th Venice International Film Festival, “Lisette Carmi, un anima in cammino,” and her photographs have been shown in several exhibitions—including the forthcoming group show “Female identity through the images of five Italian photographers, 1965-1985” at the Centro Pecci in December.

Her archive spans a breadth of subjects, which she tackled in a ruthlessly pioneering fashion. She did a reportage on Genoa’s wharfs—which she gained access to by slyly pretending to be related to a dockworker — and highlighted the miserable exploitation of those employed at the port. The City of Genoa commissioned Carmi to document its hospitals, for which she photographed the birth of a child with thrilling, breathtaking frontality, a veritable paean to the female body. She took portraits of 20th century icons, like the poet Ezra Pound, the painter Lucio Fontana, the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, and a cast of important Italian intellectuals and creatives. She also documented her far-flung travels to Afghanistan, Ireland, Latin America, Nepal, and Israel.

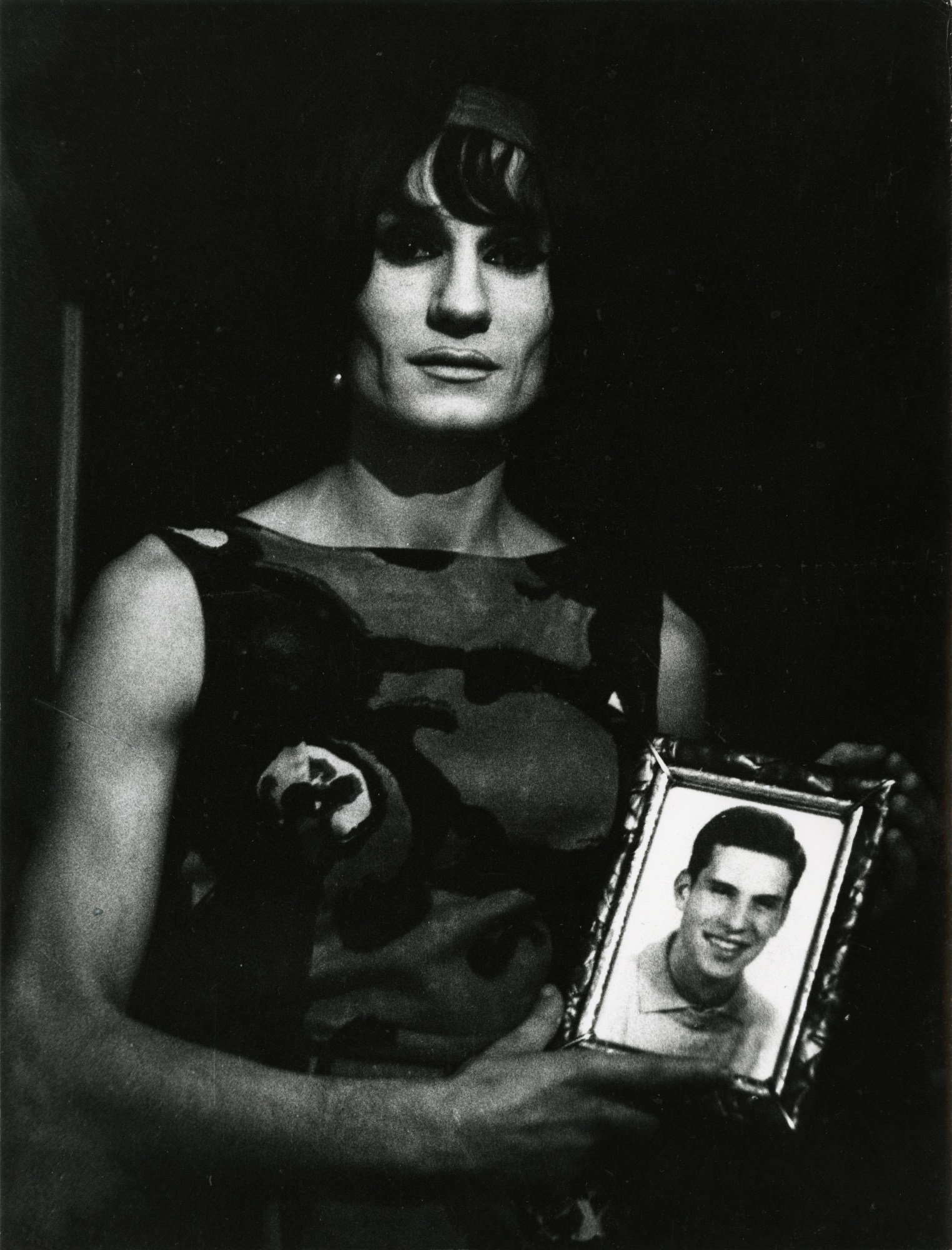

However, it is her intimate series on Genoa’s transvestites — I travestiti — that is perhaps her most trailblazing. On New Year’s Eve in 1965, she was invited to a party gathering the transvestite community together. Thereafter, she befriended the group and shared many intimate moments of their day-to-day realities. “She is the first to document the LGBTQ community in Italy,” noted Roxana Marcoci, MoMA’s senior curator of photography, in discussion with Francesco Vezzoli for an exhibition at Fondazione Prada in Milan, “TV 70,” which included Carmi’s work. Marcoci was moved by the way Carmi framed the experience, citing the photographer directly: “Thanks to [the trans community], I learned to accept myself. When I was a child I looked at my brothers, Eugenio and Marcelo, and I wanted to be a boy. I knew I didn’t want to get married, and I rejected the roles society assigned to women. The transvestites made me ponder over the right that we all have to determine our own identity.”

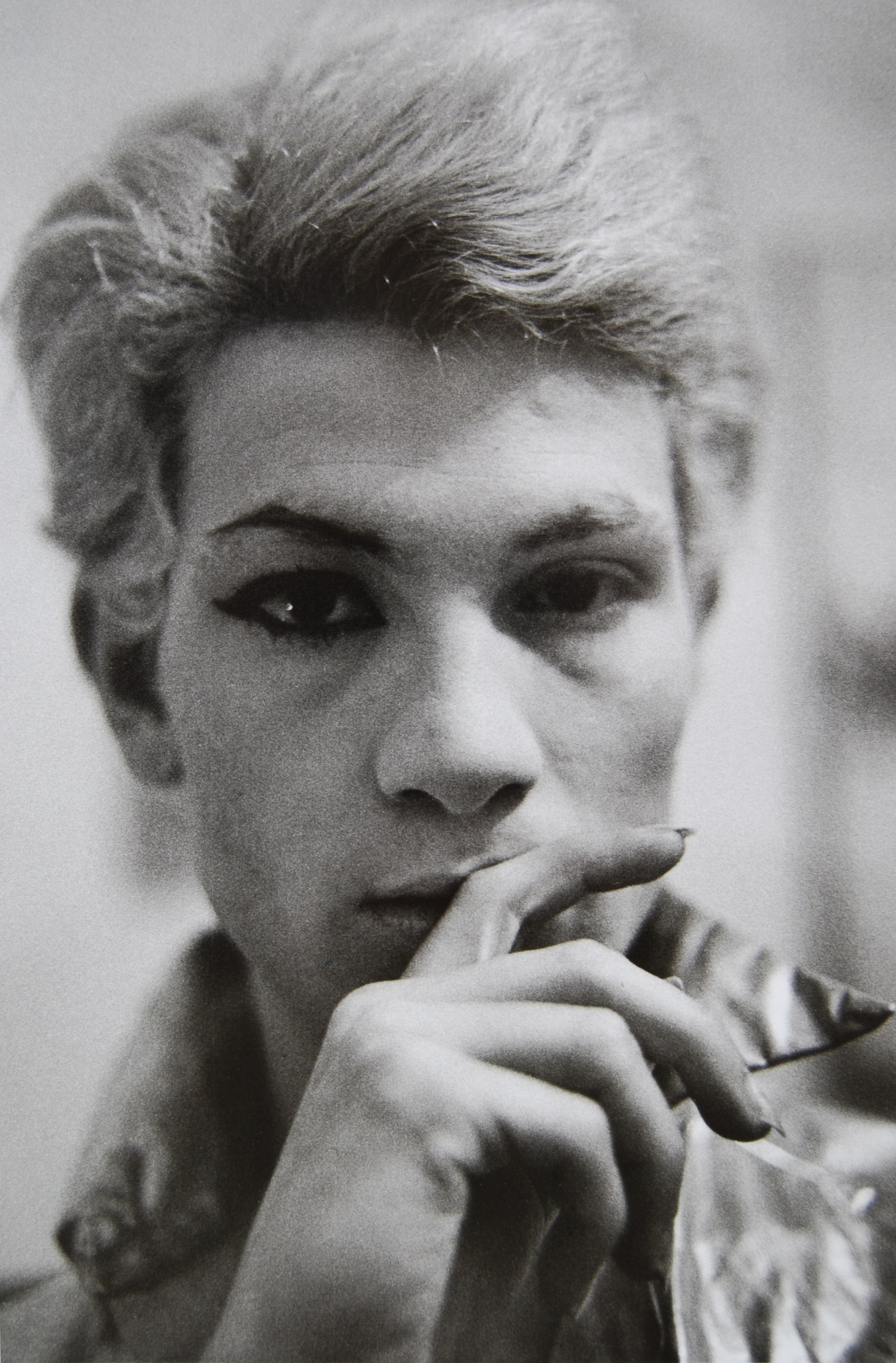

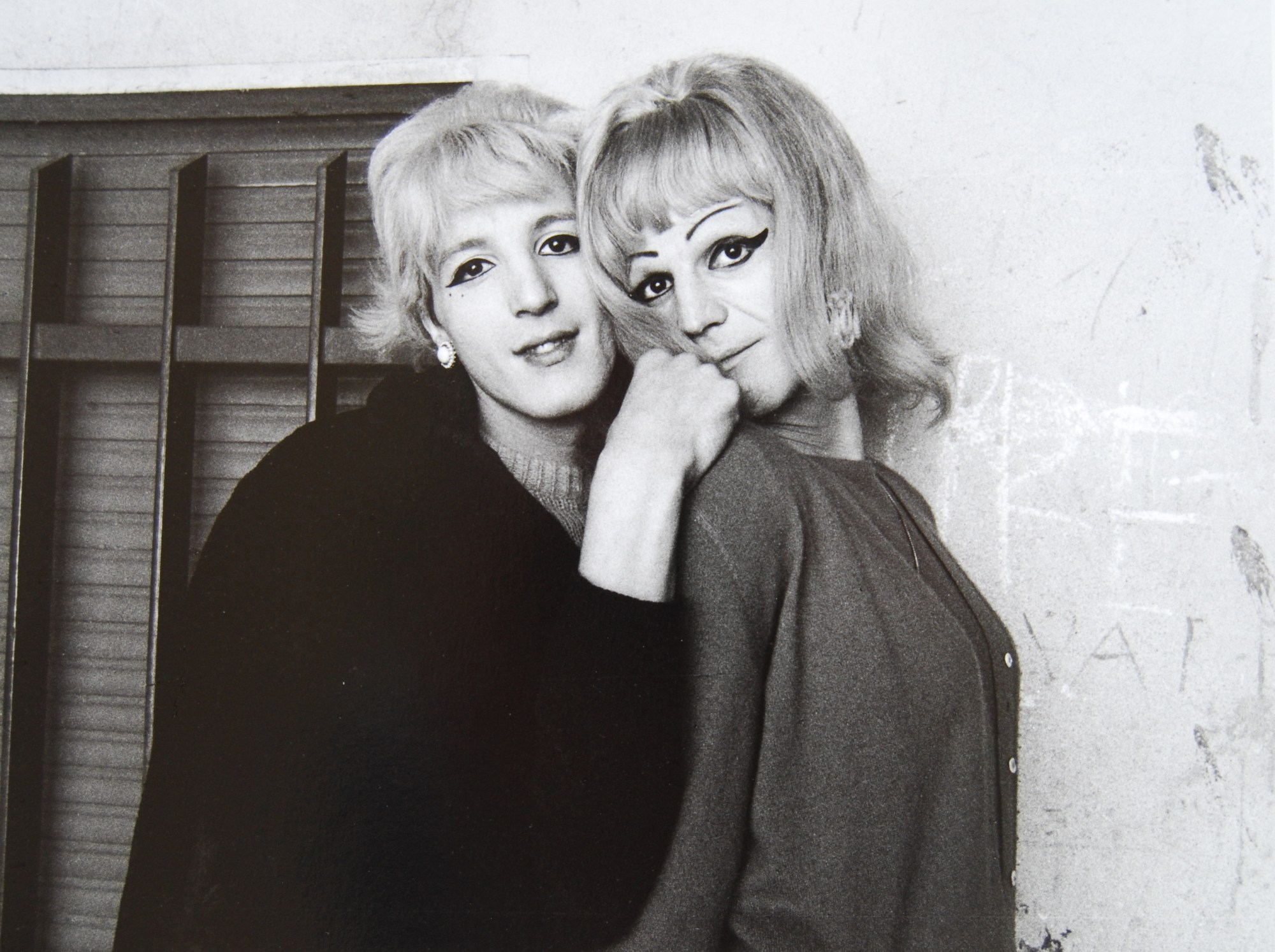

Carmi chronicled these women with a tender gaze, exempt from judgement and never veering into invasive voyeurism. Gender identity was entirely outside the vocabulary of the time: it was addressed solely in scientific studies, but Carmi was never clinical either. She lent dignity and beauty to the masked realities of sex work. She normalized the gestures of the women dressing up, applying make-up before mirrors, doting on each other in moments of lounge-y camaraderie—instinctively revealing, in these innocuous moments, the sensuality of their silhouettes. The shimmering pink lips, kohl-rimmed eyes, lace-trimmed slips, and sheer stockings have the feel of a girlish confidentiality, a grown-up sleepover party.

French art historian Bertrand Prévost wrote about the series in loftier terms, in an accompanying text for the exhibition “Below the Mantle,” which featured Carmi’s vivid color photographs at Galerie Antoine Levi in Paris this fall. Prévost noted the “pictorial approach” of her images, which he equated with “ a modern variations around ‘Venus à sa Toilette.’” The thoughtful compositions, the graceful postures, and the cinematic lighting echoed the works of canonical painters. Carmi managed to encapsulate “an unusual Caravagesque mood,” Prévost said admiringly, further name-checking iconic tableaux like Ingres’ “La Grande Odalisque” and Manet’s “Olympia.”

Still, Carmi saw herself less as an artist and more of an anthropologist: creating important documents of communities who deserved to be represented. “Her images evoke certain paintings,” agreed Giovanni Battista Martini, who curated the Carmi show in Rome. “But if you ask her, she absolutely denies it,” he chuckled. “She never asked anyone to pose. She always wanted to be direct. She said: ‘I wanted to photograph a moment of truth.’” The intention behind her photographs was to create heightened awareness: “She wanted to give problems public visibility,” Martini noted. “A book was the easiest way to shine a light on a reality that was otherwise hidden.” Carmi struggled to find a publisher—the provocative nature of the images in ultraconservative Italy was hardly a comfortable match—and yet, still did manage to publish the work in 1972. Booksellers did not want to promote it, deeming its theme shameful and scandalous (Even today, the shift hasn’t been as progressive as one would hope. In Italy, no anti-discrimination laws regarding sexual orientation or gender identity have been enacted at the national level).

The documentary nature of Carmi’s work doesn’t diminish the aesthetic impact of the images. In fact, one could argue that highlighting the beauty of a marginalized identity honors it even more meaningfully. “They were not depicted as a ‘phenomenon,’ but as people,” Martini said of Carmi’s spotlight on the trans community. “She was successful in showing them the way they wanted to be seen.”

“Lisetta Carmi. La bellezza della verità” — “The beauty of the truth” — is on display at the Museo di Roma in Trastevere (on view until March 3 .