Nicolas Roeg is never surprised when people tell him that his most well-known films continue to influence fashion and popular culture decades after their creation. Today, we’re passing part of a lunch hour in exactly the kind of overstuffed, panelled library you’d expect an 82-year-old English eccentric to inhabit as a matter of course. The mustiest things here are well-used books and the windows look onto one of the Notting Hill streets first made famous and Bohemian in Performance, Roeg’s 1970 debut about a bunch of spivs who imprison a drug-addled rock star played by a post-Altamont Mick Jagger. It was the opening salvo in a run of films — Walkabout, Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell To Earth — that expressed the menace and style of the first half of that decade so brilliantly that they remain touchstones today.

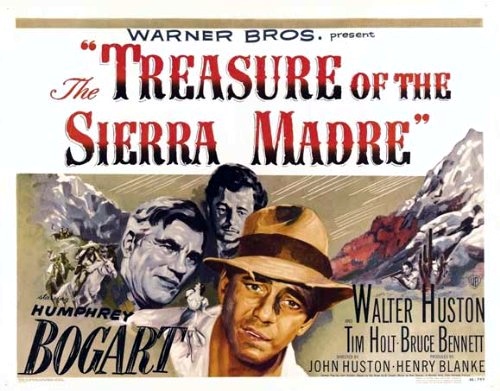

“I’ve never been able to do those talking head interviews and events because I’m the kind of person who changes my mind constantly,” confesses Roeg, who manages to be both intellectually demanding and favourite-uncle twinkly at the same time; he also understands that the world and all who sail in her are in a constant state of flux. “One moment of realisation can split up into a thousand ways of doing something. It’s like in Treasure of the Sierra Madre, where they can’t see the gold beneath their feet for ages: sometimes when you’re touching upon things that should be kept secret, like a premise in a film, it will strike subconsciously instead of taking the form of a confrontation people wouldn’t like. Later, in a more favourable environment, it will sink in and you’ll see the truth in something.”

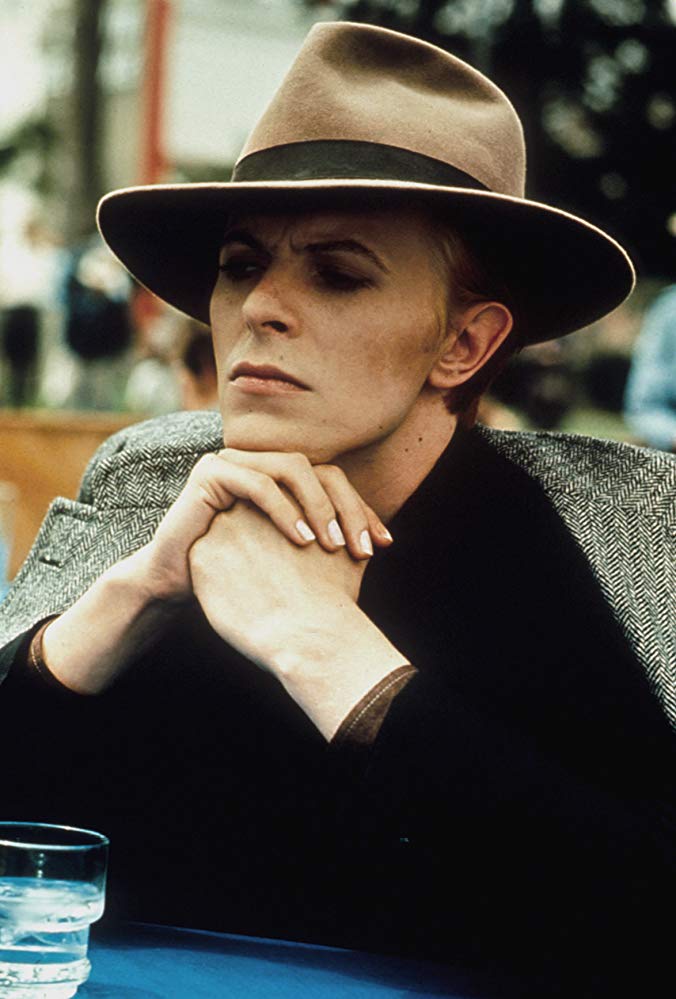

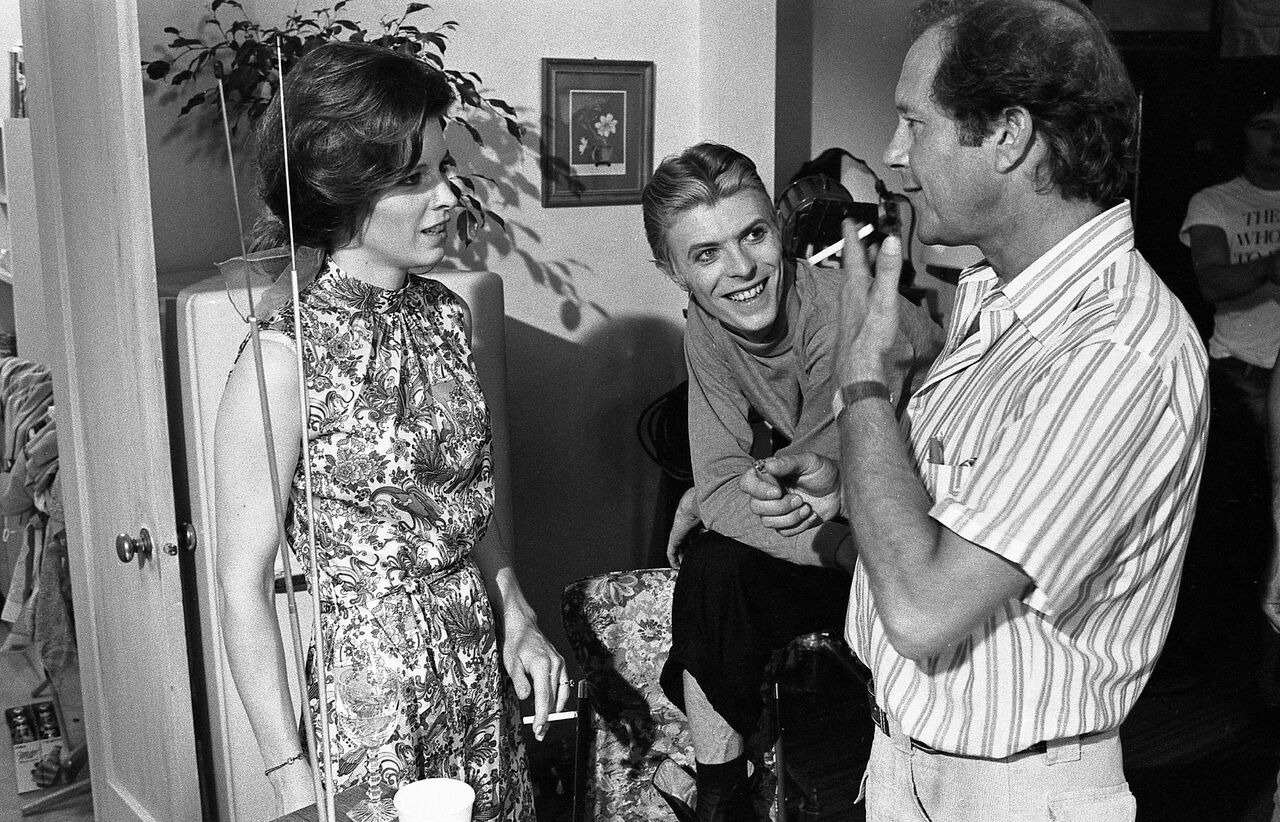

In other words: what goes around, comes around — and Roeg’s films are comets with extraordinarily long tails, especially The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) where the previously untested David Bowie played the alien Thomas Jerome Newton as another kind of Major Tom, stuck in America while his waterless home planet dies of thirst. “I’ll never forget this: we had rushes and a producer from the studio came up to me and said ‘we’re rather worried about the performance’ and asked me to have a word with David Bowie”, Roeg chuckles. “So I had to tell this man, ‘he’s an alien. Would it be better if he played it like Robert de Niro?’ What kind of performance was he supposed to give? He was wonderful, and the executive had inadvertently paid him the greatest compliment of all: if he landed, you wouldn’t believe him. The producer wasn’t wrong, but he certainly wasn’t right — he just couldn’t see the gold under his feet.” We still can: the performance that Roeg coaxed out of David Bowie informs the red-letter days on 2011’s fashion calendar, half-Ziggy, half Low, an angular totality. Although the director is amused by designers’ lasting love affair with all things Bowie, he knows an icon when he sees one. “Which version are they imitating this time?” Roeg wonders. “Are they dyeing their hair, too? Nobody but Bowie had hair like that back then. We don’t appreciate how long ago it was until we remember things like that! People dyed their hair, but not that colour. I remember the hairdresser complaining, ‘this is not at all natural…’”

Based on an obscure piece of pulp fiction by Walter Tevis — whose only other title of note became the Paul Newman vehicle, The Hustler — The Man Who Fell To Earth was a departure for director and audience alike, but only superficially: Roeg’s films use the enormity of environment and landscapes to demonstrate human insignificance in the face of nature. “That’s a good observation,” Roeg allows. “I am also drawn to foreign locations because I don’t think we see what is influencing us in our own cities — you never notice random things the way you do when you’re not at home. I’ll have visitors to stay here in London and when I take them out, they’ll ask me ‘what’s that building over there?’ I always make something up about it, like a bad tour guide. Who notices the Admiralty in their own city? In foreign cities you do, because you’re a stranger in a strange land and people behave in a curiously different way outside their own world. That’s what draws me; also I like the idea of the total stranger — and you can’t get any stranger than being from another planet.” “In life, we don’t see what’s happening half the time; we only know the past and the moment, because we are in the moment all of the time. That was an enticing thought to make a film and construct a plot around,” explains Roeg, who says that Bowie’s own outsider-dom anchored, complemented and mirrored the alien he portrayed, in that he could hide in plain sight with his weird English accent and odd clothes, hiding the outer-space foreignness required by the character of Newton with another form of oddity, slightly more familiar but no less bizarre in the eyes of the Americans encountered in the film. “When Newton goes to the pawn shop and meets the little old lady, he gets his linguistic emphasis slightly wonky. Oddly enough, I think in many ways his performance was closer to the possibility of coming from another planet than something like a three-eyed alien from a space opera, but still within our experience. It’s just like when the Spanish first landed in South America with horses, a messenger went back to the other natives having seen something extraordinary and equally alien to them.”

The films lend themselves well to the magpie needs of fashion; they are lateral, non-linear depictions, influenced by Roeg’s start as a cinematographer and unit director, with a dash of William Burroughs’ cut-up technique employed as a creative strategy by many in the 1970s including Bowie himself. Roeg has his own theories as to how the films stay relevant to this day. “I’ve tried to reflect and hide something in the films that I believe in — that change is happening the whole time. My God, we’re living in a time where huge changes are rolling through society and it fascinates me. It’s extraordinary — for example, I was in Egypt 18 months ago and didn’t see or feel any strain or upset in the people, so seeing them now is startling — it was the unhappiness of a people kept down and kept secret outside until it was no longer possible to suppress it.”

At the same time, like all of us, the character needs an intimacy he can never achieve; he may not be normal but Newton’s feelings are just as real. “I feel that we are still asking ourselves, ‘what is normal?’ when ‘normal’ is not a word I really use,” Roeg argues. “It’s a very difficult thing: we still have to lie about our hidden thoughts. Some lies aren’t bad — you lie to someone who might be near dying to protect them, for example — but I like the idea that we secretly connect with people on the basis of things that are hidden, because on one level, they’re not.” The fishes-out-of-water amongst us — fellow travellers are legion in fashion and pop culture — are drawn to the film to this day for reasons of identification which are anything but shallow. “The paranormal sci-fi character is waiting to be discovered and the truth of the film, the premise coming through, was that we all have our secret lives. And you mustn’t divulge those secrets because it will never be interpreted in the way you’d like,” Roeg cautions. “In the movie, Newton imagines he has an intimacy with Candy Clark’s character and decides to show his real face after a row. Then he comes back from the bathroom with his alien eyes and she’s like, ‘shiiiiiiiiiit!’ She doesn’t love him that much!” When all is said and done, the lingering vision from the film will always be the cracked and tortured soul who can’t return home. Roeg is more than satisfied with that, because within the greatness of his films he has defined an icon for all time; David Bowie, he feels, is beyond the baggage people hang on him. “It might sound lopsided and wrong, but he has an originality that is always changing,” he attempts to explain. “He stayed as ‘the man who fell to Earth’ for a couple of years, into Low. I went to a concert at Wembley about nine months after we’d finished filming but the movie hadn’t yet come out, and all the young kids arrived ‘as’ David Bowie, but like he’d been before — and then out he comes as this completely new person and it was fantastic! The line in the movie, ‘the world is ever-changing, Mr Farnsworth, like the Universe…’ comes to mind. He’s ever-changing and he’s extraordinary. What would you label him: a pop singer, an artist? He’s David Bowie, and he is a most individual person.”

This article first appeared in i-D’s Exhibitionist Issue No. 312, in the spring of 2011.