For the past two decades, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize has celebrated artists who, in the last 12 months, have published or exhibited a visual project or body of work that offers a new way of communicating with the world. Ranging from introspective explorations of the self to vast, expansive studies on societal and environmental changes; specific projects to wide-reaching career retrospectives; although the nominees’ works often vary in scale, the thread that unites each is an exhilarating sense of new possibility within the medium.

Launched in 1996 by London’s The Photographers’ Gallery and the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation (and formerly known as the Citigroup Photography Prize before Deutsche Börse began sponsoring the prize in 2005) the list of previous recipients takes in many of our generation’s most evocative visual artists; Richard Billingham, Rineke Dijkstra, Anna Gaskell, Juergen Teller, Dana Lixenberg, Richard Mosse.

As with this year’s Turner Prize nominees, the four artists shortlisted for the 2019 award have created work that plays along the lines of artistic and esoteric inquiry. Laia Abril’s On Abortion goes deep into the complicated history of women’s reproductive rights and the plight for safe, legal abortion. Susan Meiselas’s Mediations brings together decades of work documenting conflict zones across the world. Arwed Messmer’s RAF –– No Evidence / Kein Beweis utilises old investigative imagery used as evidence against the German far-left extremist organisation, Red Army Faction, as a means of better understanding how repurposed photographs can offer a different way of engaging with history. Finally, Mark Ruwedel’s Artist and Society: Mark Ruwedel looks at the different societal and environmental factors he’s studied over his career that have created lasting impact on our geographical landscapes.

As individuals, these projects exemplify the breadth in possibility in photography. As a group, they speak to our collective, ever-heightened awareness of the human impact on the world, traversing the social, political and environmental, and asking as many questions about ourselves as the photos themselves seek to answer. In the words of Anne-Marie Beckmann, Director, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, “This year’s shortlist refers in an impressive way to the diversity of the medium of photography as an artistic form of expression as well as to its relevance in today’s world. The nominated projects include classic black-and-white photographs, archive-based positions as well as reflecting highly topical issues alongside strategies for understanding the past.”

Here, we meet the four finalists to discuss what they set out to achieve with their work.

Susan Meiselas

Mediations exemplifies the immersive approach you take to your work. Can you say a bit more about the ways that this retrospective reflects your practice as a whole?

The title Mediations technically draws from a show I did in 1982, which looked at how my photographs from Nicaragua circulated, by sharing the process in which I made selections for the book and the choices that were made for distribution in the media.

Two key ideas are embedded in the show, the relationships that evolve with my subjects and the images themselves as they are revisited. The notion of ‘mediation’ is about acknowledging the intervention, making the process more visible and raising questions about the practice of making photographs, and how those photographs relate to the people in them, over time.

The exhibition encompasses a lot of different stories. What has been the most challenging to capture?

Each room in the exhibition focused on a distinct series from four decades of work. The main challenge was to compress and thread through diverse materials to give viewers the experience of the thinking that led me to create each body of work.

Probably the most ambitious is the room on Kurdistan, which brings various stages of that project to view, from documenting the visual evidence of the Anfal campaign, to gathering historical photographs, to the ongoing collection of stories from the Kurdish community in the diaspora today.

Spanning five decades, this retrospective tracks a period of monumental change. Can you say something about how these shifts are documented in your work?

The greatest change within these decades is obviously the shift from analogue to digital photography. Digital has created a great opportunity for a lot of experimentation. We showcase still photographs –– framed or projected with sound or text; video clips alongside analogue artefacts with both contemporary and historical prints; magazine tearsheets in contrast to images shown as murals made out of mesh –– which could only have been produced in the digital age. I think throughout the show you feel the medium of photography transforming the creative potential for image makers and storytellers.

Laia Abril

Can you talk about your motivations and intentions for this project (On Abortion)?

After my five-year project about eating disorders had come to an end, I wanted to address larger, related themes such as sexuality, identity and gender. Over time it transpired that all my research and ideas were really about the different ways society had controlled and continued to control women and that I was actually putting together chapters of a history on misogyny. This historical approach helped me put into perspective the long fight for women’s rights and human rights and understand that we continue to be at risk of losing some of those rights. We all rely on government policy to defend our freedoms, at the same time it is up to us to inform ourselves and build an awareness as we can’t take anything for granted.

I didn’t plan for On Abortion to be the first chapter of the larger project [A History of Misogyny]. But I realised that my own rights could be in jeopardy when the Spanish right-wing government submitted a proposal of restricting our abortion law. At the same time, Trump’s campaign showed the rise of right-wing politics around the world, and it felt that things were just getting worse. Realising the shocking reality of the repercussions of not having free and safe abortions made this a priority and an important start to identify the origin of misogyny and why it continues to the present day.

How long have you been working on it? And how did you gather and organise the material?

I started to shoot the series in the summer of 2015 and the first exhibition of the project was held in the summer of 2016 at Les Rencontres d’Arles. My idea was to visualise the invisible, the intangible, the stigmatised; to represent the repercussions for women of different backgrounds and across history through testimonies from all over the globe, historical documents, objects and vernacular material. I wanted to show as much diverse material as possible that would help audiences understand some of the real consequences of the lack of access to safe abortions: women dying from botched illegal procedures, women being imprisoned, doctors killed by fanatics and forced motherhood. For the book, I had to rewrite the whole project. An exhibition is a public and physical experience, a book is a private and personal experience. I wanted to include more diverse opinions while also offering a single voice that could bring these different positions and experiences together. I wanted to create a serious and committed conversation with the reader, where I could disclose the personal and terrible stories and he or she might be able to understand and relate.

How does this body of work fit into your wider [ongoing] series, A History of Misogyny?

I am currently working on the series “rape culture” and “mass hysteria”, I am still looking for answers, raising questions. I’m looking at the broken system and always trying to understand why, how…? In my practice I look at the most complex and uncomfortable aspects of our present time, trying to bring some light to the darkest shadows. I believe that through starting conversations, through empathy and compassion, we can actually impact people’s lives. I am just one piece of the puzzle, there are other photographers, other artists, journalists, writers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, activists.. We are all part of a big picture and I’m trying to contribute by producing images that might influence people’s ideas, thoughts and actions.

Mark Ruwedel

What inspired you to begin documenting the human impact on natural landscapes?

When I was quite young as an artist/photographer, I was inspired by the work of the “New Topographics” photographers, particularly Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams. Their work suggested to me that landscape could be a means of social inquiry. I was equally interested in the work and ideas of artists such as Robert Smithson. Through extensive, cross-country travel, I began to identify subjects that addressed the relationships of the social, technological and cultural with the natural world: a dialectic between the earth being both the field of human endeavour and an agent of historical change. Landscape may be seen as an archive of the results of these forces.

What role do traditional image-making techniques play in your process?

I make my work with “traditional image-making techniques” for the most part. I am in love with the darkroom and the traditional black-and-white gelatine silver print: I believe that this is the visual language best suited to my concerns. I enjoy the qualities of the hand-made print. I consider what I make to be both an image and an object and see my work as being in dialogue with various aspects of the history of the medium. (Not a Luddite, I do make digital colour prints; these are from scanned analog negatives. I do not like digital cameras).

What other forms/practices do you draw on in your work?

I find inspiration in many sources: literature, natural history, art (especially post-war American art); 19th century exploration photography and late 20th century landscape photography of North America and Europe. I have a deep interest in artists’ books and make many unique and small edition books related to the concerns of my more large-scale projects.

Arwed Messmer

What led you to focus on this particular group and period of history and how does it reflect your practice and approach?

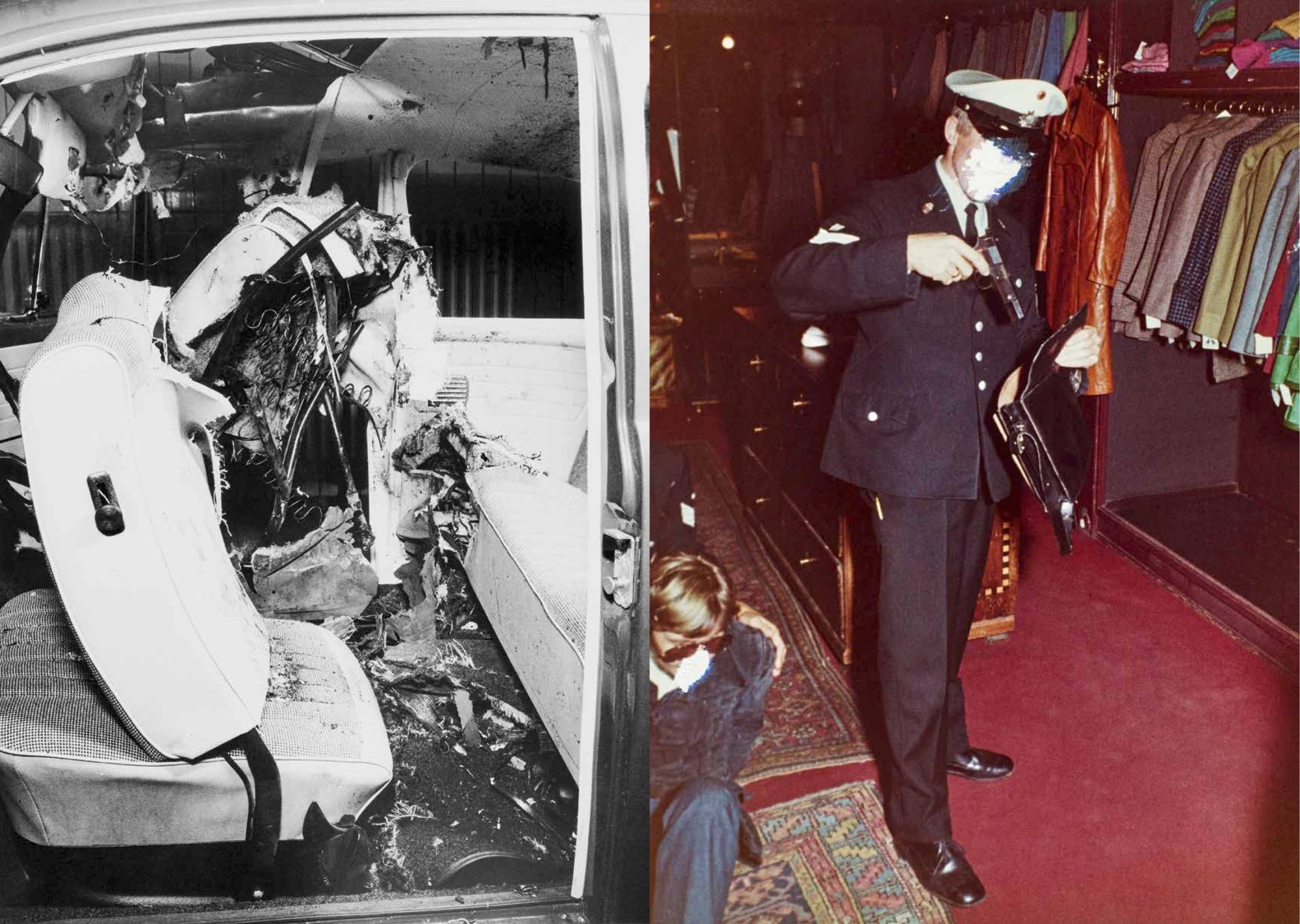

Following extensive work on the Berlin Wall archives (Taking Stock of Power, 2011 and 2016) and the visual legacy of the Stasi, the East German domestic intelligence service (Reenactment MfS, 2014), it was an obvious step for me to tackle a specifically West German theme as well. A great deal has been written and recounted –– from a journalistic, historical, literary, and filmic perspective –– about the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the German Autumn of 1977. In this respect, it is already a crowded field, an area offering many angles for research, editing and reflection. Initially, the question I asked myself was whether my technique of “taking a second look” would allow me to add anything new, relevant, or hitherto unseen to the subject. Not in terms of an investigative coup –– simply unearthing unfamiliar images –– but rather by drawing on material that has been available to us for quite some time and examining it from a perspective that diverges from the classical historical approach which has thus far determined how these archival records have been looked at.

In what ways does your treatment of these archival images seek to alter our perception of the group?

For decades West German left-wing terrorism has been visualised by the relatively small number of photographs in circulation. These images have been reproduced over and over again and define Germany’s collective visual memory in relation to this topic. To put it concisely, I was interested in the pictures produced by the state that are positioned to both the right and the left of those that have so far made it into the history books. RAF – No Evidence is not a historical project on the RAF but rather an exhibition about images outside the canon of photographs recording this conflict. My work also has an ethical dimension: What images can be shown? How can they be shown? And why should we look at them? This touches on a key point in the debate about images that not only serve as historical documents but also have their own aesthetics and can offer us a means to engage empathically with history in ways that are difficult to predict or control.

What does this project say about the role and perception of photography then and now?

All my work over the last 25 years has dealt with issues surrounding German post-war history. For around 10 years now, I have been working primarily with a body of utilitarian images produced by the state that I have researched in different archives. These photographs, which are, in principle, all freely accessible, have provided the visual basis for my projects. They might include, for example, images that had temporary relevance as documentation for building authorities or even material that was used as part of forensic investigations. My approach to these types of pictures is based on fundamentally shifting their function: for me, the photo is no longer evidence of what happened and how exactly it took place — rather, I see it more as a form of contemporary eye-witness that can now be reinterpreted from a distance.

In the words of photo historian Florian Ebner, “he [Messmer] uses the potential that photography has, which, even if it is not an impartial instrument, is still characterized by a particular form of indifference.”

In contrast to the work of a photojournalist who may have a particular political angle, the outstanding feature of police photographs, when examined retrospectively, is the specificity of the context in which they were taken and the relative lack of ambition in the photographers responsible for them when it came to framing and composing their images.

Each of the shortlisted artists’ work show at the The Photographers’ Gallery between 8 March and 2 June next year, before moving to Deutsche Börse’s headquarters in Eschborn/Frankfurt. The winner will be announced 16 May 2019 and awarded £30,000.