Athlone, the largest town in Ireland’s predominantly rural Midlands region, was long considered strategically important due to its centrality and its sitting on Ireland’s longest river, the Shannon. Consequently, the town was besieged twice during one bloody war in the 17th century. Nowadays, in light of an increasingly diverse music scene and a more tolerant secularised Irish society, Athlone lays claim to being the tactical stronghold of Irish drill: a localised interpretation of the nihilistic rap trend originally concocted in inner city Chicago by listless teens, now being blamed for fanning London’s knife crime crisis.

At just 18, J.B2, formerly a member of pioneering Athlone crew 090, helped skyrocket Irish drill to a new million-views stratosphere last month with his collaboration with UK drill artist Russ. The modest online successes of the newly-imported scene were fomented by collective and label Dearfach, whose YouTube channel Dearfach TV was founded in 2017 but truly began making waves in early 2018, now clocking up tens of thousands of views when videos drop.

In just over a year, emboldened by the DIY inventiveness of English acts, Irish drill — courtesy of 090 and Dublin crews AV9 and D15 — has begun outpacing itself. Dearfach, which has a roster of 13 acts altogether, is now the home of Reggie and J.B2, two of the scene’s most irrepressible voices. A music video for 090’s Fix My Ring released in May is considered, amongst the scene’s organisers, to be the catalyst for the nascent scene blowing up.

Ireland’s scene is decidedly urban-centric but unlike drill’s historical roots, does not exclusively lie at the intersection of inner-city teenage ennui and impoverished (and mostly forgotten about) communities, and does not have the same moral panic and indignation swirling around it yet. Athlone rappers Jug Jug and Cubez currently make up 090 while AV9 — Chuks, Shift, Rose — and D15 — Jordy and Jay Bibi — emerged from suburbs just north of Dublin City.

The first thing you will notice about the youthful artists who navigate this scene, considering their Irishness, is their London Multicultural English accents and slang gilded with an Irish lilt. Among Irish drill’s most visible exponents, almost every artist has assimilated the same patois as their UK peers: using slang like “ten toes,” and “splash,” to conjure up an existence forever looking over your shoulder.

Sequence, an entrepreneurial and creative force in Irish drill, who manages the 090 crew, denies that this means that the movement’s co-opting of language is derivative or appropriative. Instead, he says, it’s deference to what these young, impressionable artists have grown up listening to across the pond. The lack of an Irish accent with black rappers, he hints, may involve a subtle, racial aspect as Ireland contends with the abstract, constantly in flux notion of Irishness. “Over in England, they were just lucky enough to build a style and you can see how it worked out for them,” he says. “The Irish accent is not as appealing to [audiences] as people think… I don’t think people would take a black Irish rapper rapping in an Irish accent seriously yet.”

The scene’s breakout star, J.B2 is as idiosyncratic a drill rapper as any. His playful flow, a deliriously choppy mix of Migos’ Takeoff and drill auteur Headie One, underscores a kaleidoscopic lyrical vision not limited to violence and braggadocio, which has made an impact in drill circles. “My temper steamy, you can see the condensation on his bludclart face,” he rapped in a recent video.

“Listeners rely on the London accent because they’ve adapted to the drill music they produce — that’s where I step in, listeners are trying to adapt to my lyrics and accent,” J.B2 explains, citing Irish drill’s own esotericism. Many of the artists accept that they are heavily influenced by their UK peers but resolutely refuse the idea that it is mimicry. “I think it’s different ‘cause it’s Ireland. Different scene, different ends, different beef, different history,” offers Reggie, 19.

In the UK, the scene is largely constructed around pre-existing gang rivalries. Statistically, however, Ireland has quite low levels of gang crime, even in inner cities, and is one of the safest places to live in the world. Considering drill’s violent imagery, Irish artists gravitating towards their UK peers stylistically — some of whom have been banned outright from posting videos, while others have their lyrical content monitored by the Met police — poses a question that goes deeper than binary political scapegoating. When, and who decides, what is art for art’s sake? “Some of these boys are stressed and the only way to release it is to write everything on your mind on paper. There’s no point hiding anything, even if it is anger,” says Sequence, who records Afro-bashment in the vein of J Hus.

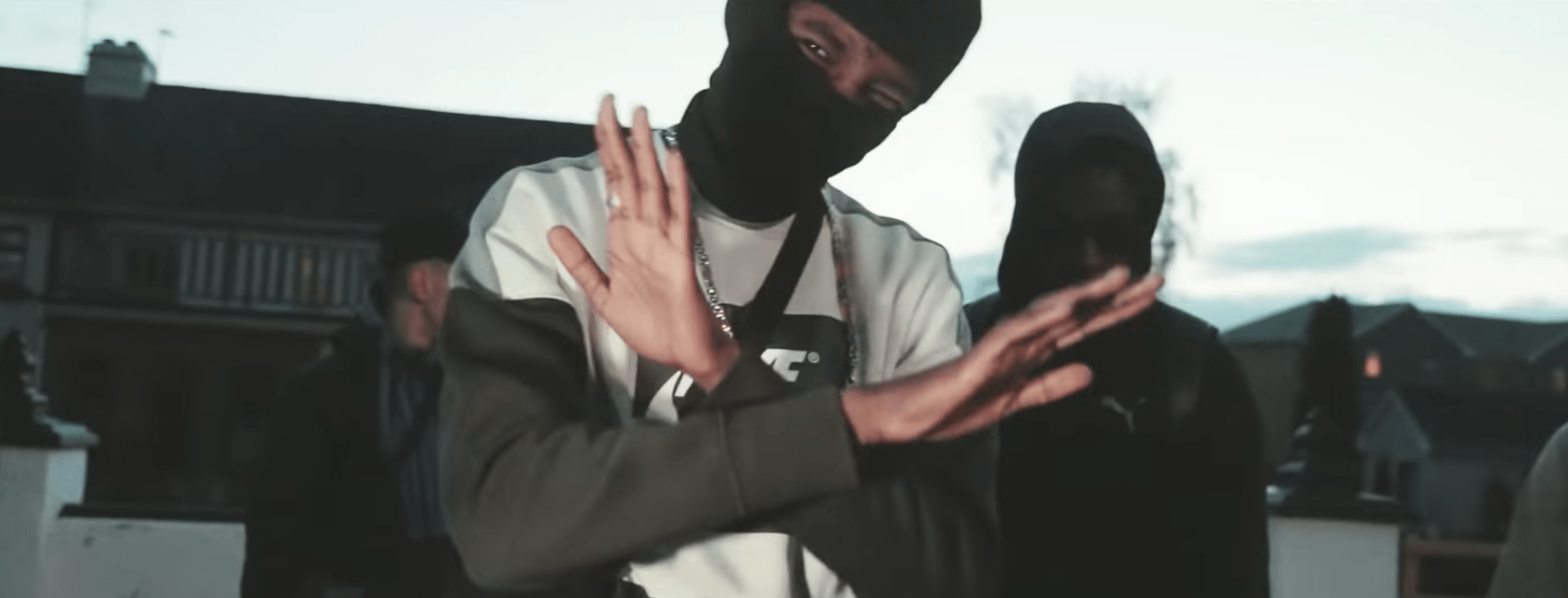

In drill’s Irish configuration, the lyrics are more often than not narrative-driven and diaristic, regardless of their authenticity. Some of the rappers are in secondary education, while others are in college. These are essentially kids who, according to J.B2, are “merging into the drill scene simply because they can relate and rap about what happens in their lives.” Perhaps the most commanding rapper emerging from this new guard is Reggie, originally from Dundalk, close to the Northern Ireland border, whose devilish, tonally-dark timbre and satin smooth flow belie his young age. “I was always very good at spitting rhymes. My guy Shinyy showed me how to write and Cubez and J.B2 got me into the studio. Never looked back since,” Reggie says. Elsewhere, on No Hook, Chuks of AV9 shines brightly in spite of his balaclava-hidden face. He peppers his legitimately charismatic verses with inventive football references which double as admonishments to his rivals.

Complex social factors are at play in the music’s subtext; entrenched institutional racism still exists in Ireland, despite the much-reported social change. Just this month a report found that African nationals in Ireland are now the most disadvantaged group in the country’s labour market, facing discrimination at almost every turn. Second-generation African immigrants born in Ireland, like many of the young men in the drill scene whose parents arrived from Nigeria and South Africa among other places, experience discrimination, too.

These young rappers — whose ages range from 15 to 21 — have enough self-awareness to acknowledge that such issues affect their community, but are more consumed by the idea of unspooling lyrics of materialistic bombast and violence — jubilant in their abrasiveness — than they are of chronicling social ills. Performative bravado or not, they seek to transcend local-hero status.

Sequence also shoots the videos for New Eire TV — a platform he founded to showcase the scene — and he claims that the manner in which these videos are created make them stand out from what he views as a fairly one-dimensional style in the UK. Weapons are left aside; trackies are subsumed for designer clothing; shots are “creatively” predetermined; and what results sets it apart aesthetically from its forebears.

Sonically, though, all the hallmarks of drill music are there. The beats, sourced and leased from beatmakers from YouTube like in the UK, are replete with shuddering, hard-hitting, trap-adjacent drums, which serve as the backbone for eerie synths and sparse, piano-laden chimes. It’s all very pared-down and icy, much like the council estate-bound backdrops in the videos. Even so, Irish drill artists do not shy away from melody and Reggie’s most recent release is equal parts dreamy and snarling, pronouncing ‘shite’ with a typical consonant-drawling Irish cadence. His influences range from UK drill to Trippie Redd and Lil Wayne. These artists are not willing to restrict themselves to one box of austere sounds, and their relationship to a pulsating Irish hip-hop scene is inextricable.

Ireland, long known for its endless musical talents, became transfixed on the notion of purist hip-hop and, evidently, the music suffered. American accents, learned vocal tics, and increasingly stale boom bap beats were in vogue and not many could see beyond the tilted fitted cap or further than the footprint of a Timberland boot. The internet happened; the economic earthquake known colloquially as the Celtic Tiger struck; immigration brought, to the benefit of Ireland’s art scenes, the end of gimmick-heavy inertia. Artists like Kojaque, Jafaris and JyellowL are joining the already-established star Rejjie Snow as representatives of an Irish hip-hop scene bending traditions and making them their own.

In 2018 alone, Spotify curators developed a playlist dedicated to Irish hip-hop — The New Eire — and one of Ireland’s largest festivals, Longitude, to the dismay of rockists and Wonderwall caterwaulers, pivoted from indie to hip-hop and R&B. In contrast to UK drill, which clearly differentiates itself from grime and Afro-bashment, Irish drill is much less inward-facing and seeks to infiltrate the popular music in Ireland. “I think Irish drill can be as big, if not bigger, than the UK drill scene,” Sequence says confidently.

Solomon Adesiyan, who acts as the CEO of the Dearfach Group, agrees wholeheartedly, even noting that international recognition is not out-of-reach and that a new sub-genre could unfold. “I’ve been saying this for the last few weeks: The urban scene in Ireland right now is on probation — we need to prove a point to the world.”

As crews seek to become the dominant force in what is a very limited marketplace, online affrays and disagreements have already led to some minor beef, team-switching, and infighting. Undeterred, though, they go forward as one hoping to penetrate a nation’s collective consciousness. A more pluralistic society has allowed for this burgeoning drill movement, region-specific and a far cry from the anachronistic guitar bands of old and new, to develop. As the country changes, so too does its artistic output, and Ireland’s music scene is in dire need of some hyperkinetic, colourful, unfiltered, angsty, rage-fuelled rap to extend and broaden its vigour.

“I think it’s a very positive time to create music in Ireland right now. When I started out, four or five years ago, if you were making music in Ireland, people would laugh at you,” says Sequence, his voice purring with energy. “Now, the scene is growing, and it’s taking over.”