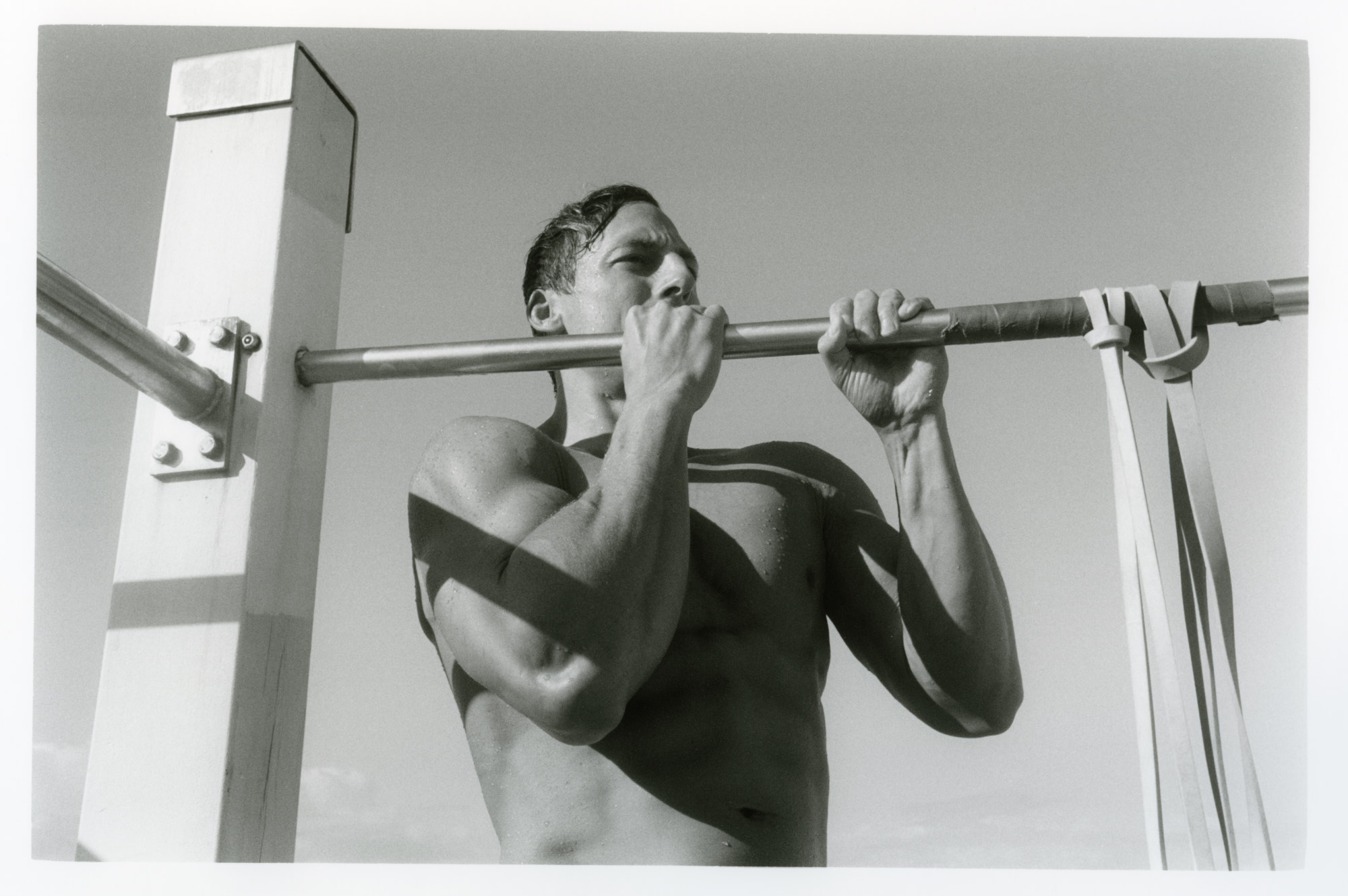

James Tolich grew up as the son of a livestock handler in the countryside on Auckland’s southern outskirts — an ocean away from Australia’s famed beaches. It was this outsider’s perspective that allowed the Kiwi photographer to capture a new side of one of Australia’s most well-known landmarks in his new series Bondi. Captured with a film-like tenderness, James’s portrayal of Bondi offers us a new perspective of the muscle-adorned macho clichés we thought we knew all too well.

Throughout the series, James digs deep to penetrate the hyper-masculine veneer of a seemingly gentle cast of characters. Following a sprawl of repeated visits, James’ tactful approach earned him the trust of locals and tourists alike, resulting in a delicate document shot with the cinematic splendour he’s become best known for. The selection of photographs below, which are set to be published as a book through Palm Studios next year, offer testament to the idea that Sydney’s star attractions leave much left to be discovered.

So, first I wanted to ask you… I always thought you were Australian but you’re not, are you?

That’s alright. I think I am too, because this is where I want to live. I grew up south of Auckland. We lived on the fringes of the countryside, because my dad was a livestock buyer. Despite having never lived on a farm, we were always around the countryside. In many ways it was quite amazing, because as a kid in New Zealand, you have a lot of space to explore. A relatively simple life I guess, which as I grew older, began to feel quite insular.

How old were you when you left New Zealand?

The first time I came to Sydney was when I was 18 — maybe a little older. At the time, I was working in a studio for a few months while I had a break at uni, and that was my introduction to the photography industry. It was different back then, the industry was more exciting — there was still a lot going on, there seemed to be more industry, if that makes sense. I learnt a lot working in that studio.

Did you always want to be a photographer?

I actually studied graphic design at uni and after I came back from working at the studio in Sydney I was more interested in photography, but not as inspired by my teachers and the environment as I might have hoped. My teacher was really nice — he would give you good grades no matter what you did, and he was super supportive, but it never left me feeling, “Wow! Photography!” It wasn’t until I went to a design conference where Derek Henderson was speaking and showing his work, which I was already vaguely familiar with. It got me thinking, “Oh wow, this guy’s got a pretty sweet job.” Also the thought of finishing graphic design and becoming a computer operator, or working in an agency, just didn’t feel like what I wanted to do. I guess it never really was my passion — I always did a lot of painting and wanted to do something more creative. So, I guess I kind of discovered photography through that.

What was it about documentary photography that intrigued you?

When I was at uni I borrowed a Hasselblad, and I was given a quick tutorial on it, and then I just set off around New Zealand taking portraits of strangers that I found interesting. A lot of the work I found inspiring at the time was documentary, portrait, landscape photography, and stuff like that — so I did that. The thing I loved most, was the idea of being able to approach these strangers, and use the camera as a vehicle for documenting people that I found interesting. As a kid, I was really quiet and quite shy, so I really had to tease that out of myself — I always found that aspect of the work really exciting. But I still wouldn’t call this series, or much of my current work “documentary”, because the aesthetics and my approach are given more consideration than what’s merely available. More goes into it.

Fast forwarding to now — why Bondi as a setting?

I’ve just always done things that made sense, and to me, it made sense to photograph these interesting characters on Bondi Beach in way that you might not be used to seeing them. Taking photographs has always helped me make sense of things; of people and places. I actually photographed one guy down there, before I left for Paris a year or two ago, and I initially thought that it would just be the one picture. But then coming back, it quickly became one of my favourite pictures so I thought that it could easily become a series. From that realisation, I decided to keep going down there, maybe twice a week, just to document it.

Can you tell me about the characters?

The guy who’s pictured facing away, with the really sculpted back looking out to sea, was their ringleader of sorts. I had asked someone else if I could take their photo, and he responded saying, “Hey mate, come on over! Take some pictures.” He was really excited to show me around and have his photo taken. After I photographed him, I showed him the image and he really liked it, which was really nice. After that, he sort of let us in, allowing us to photograph a few of his friends.

It’s been amazing, now we have complete access to these guys. There’s this big group of people down there, and they’re very open, extremely diverse, and it’s just something that, fifty years from now, would be nice to look back to. It’s just worth documenting.

You have a very distinct approach to colour and tone; can you tell me more about it?

For me, it’s always a big decision. If I’m shooting in black and white; I’m thinking in black and white. If I’m shooting in colour; I’m thinking in colour. In this instance, I just felt that I didn’t need colour to tell these people’s stories. I found the images to be more direct in black and white, and I find that there are just less distractions. It’s not like I’m doing them in black and white for them to be more elegant or artful — I just saw it more in black and white because you’re seeing these graphic bodies with the skyline, and it just feels more direct.

Was it your plan to subvert stereotypes with the series?

I always try to cut through the facade. For me, that’s the foundation of every photograph I take. But initially — I just knew that I didn’t want to glorify typical ideas of what you’d usually see down there. I didn’t want to glorify beautiful sculpted bodies, or genders, the bravado, or anything. I saw through all of that, and saw the sensitivity, and I think that came through in the photographs. There were some amazing characters that you might not have expected to be down there, that I really just thought needed to be documented.

Do you have plans to publish the series as a book and expand on it further?

Yes, definitely. At the moment, I’m working with a team on shooting a short-film of the characters down at Bondi Beach, but it’s still in its early stages. I’m also working with Palm Studios on turning it into a book. It would just be so nice to show everyone I’ve photographed, a physical document of everything that’s been happening down here. I expect that to happen next year