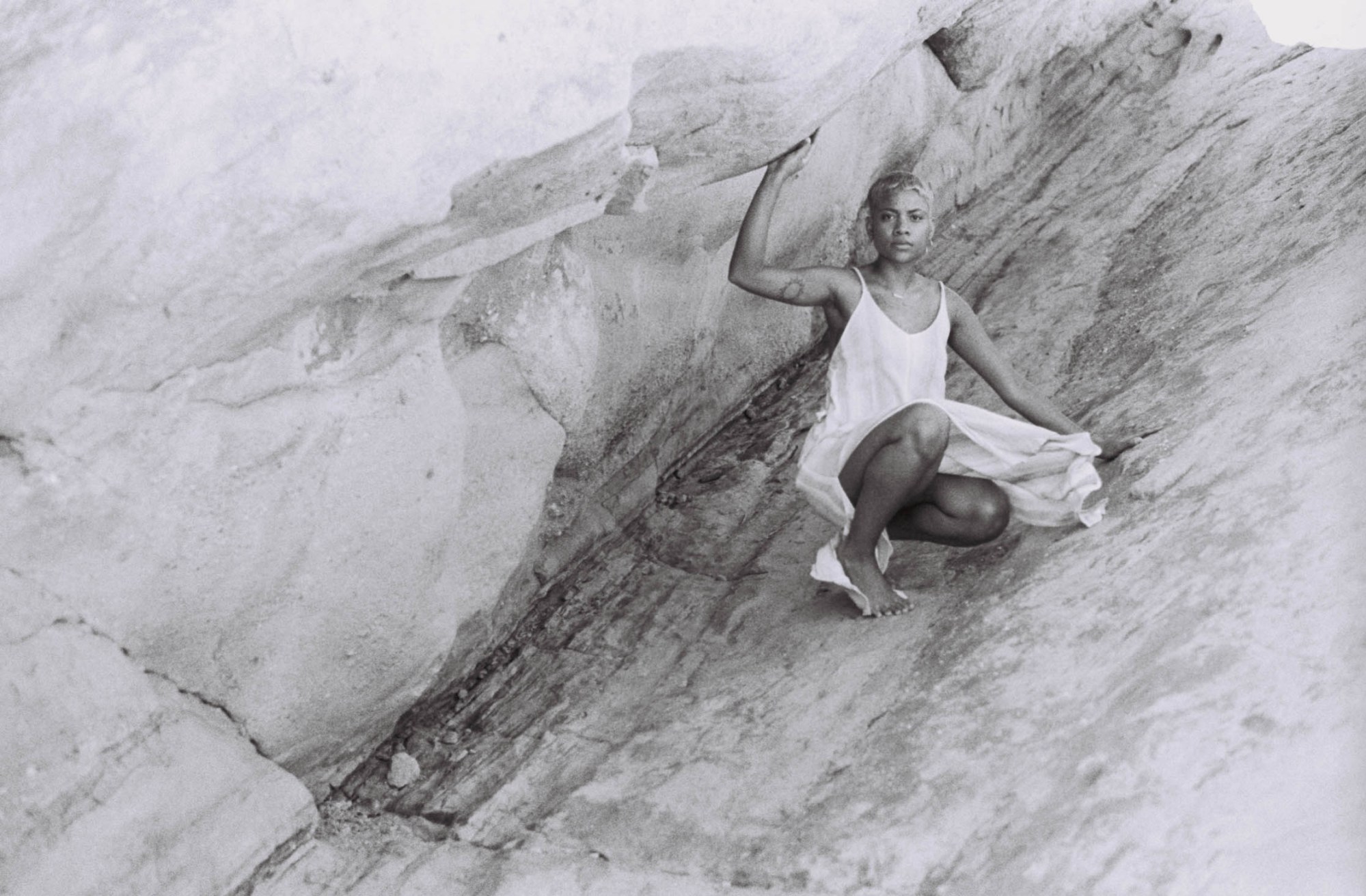

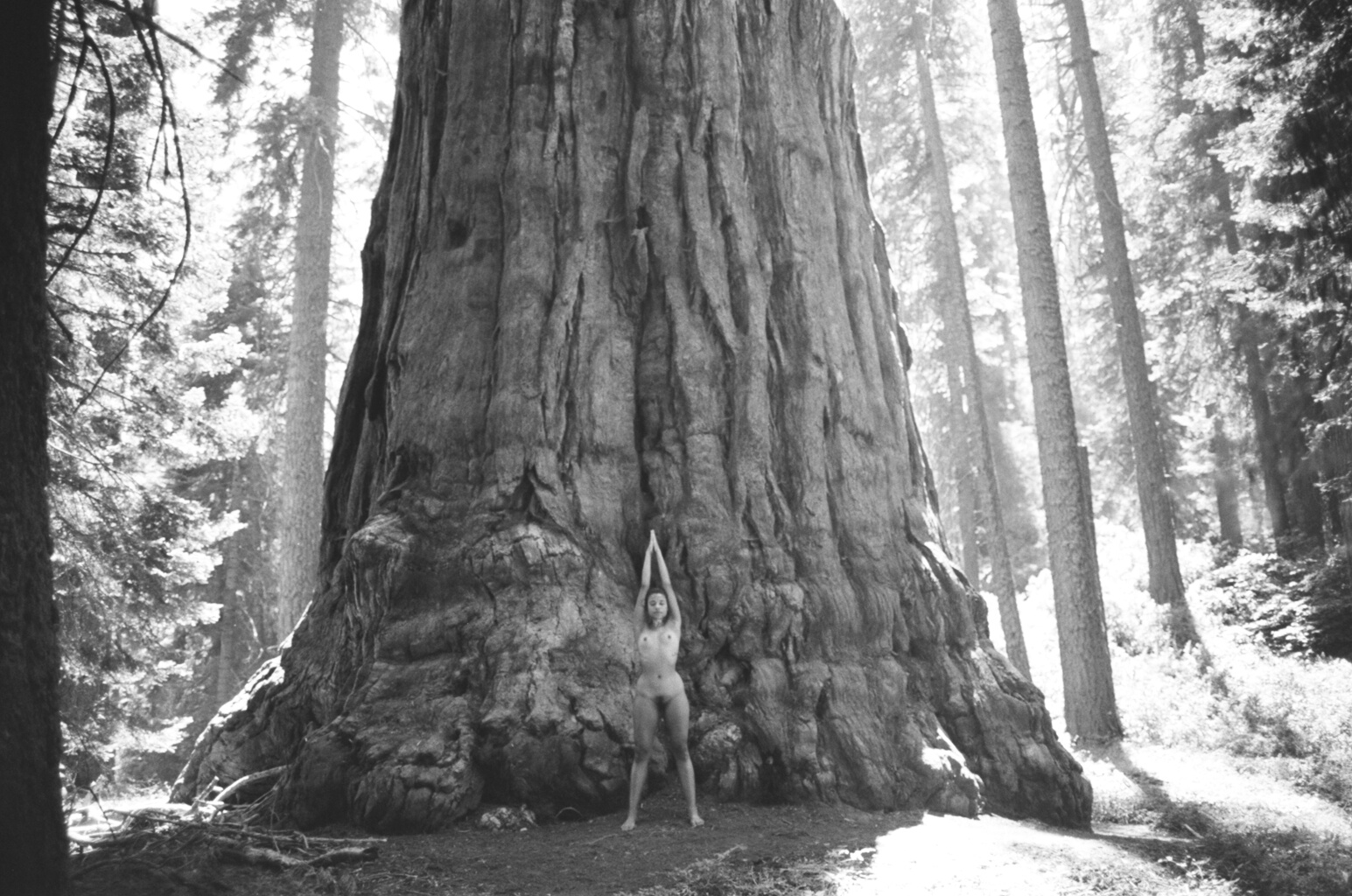

After being raped in 2013, Los Angeles-based mixed-media artist Ciarra K. Walters avoided photos, and her own reflection, for almost five years. But earlier this year, she took to the deserts and forests of Southern California, and started photographing herself in nature. “I felt like Mother Earth was calling me,” she says. “It was a space where I felt most like myself and the safest in.” In the photos from The Self-Portrait Series, as it’s now called, Walters wrestles with shame, loneliness, and reclaiming her own body in remote landscapes: In one photo, she stands in a meadow of billowing grass and gazes at her reflection in a handheld mirror; in another, she runs down an open highway in the middle of a parched desert. “This series is my way of moving forward,” Walters explains, “and finally having the courage to face who I am, and who I became, after my body was violated.” This Saturday, November 10, she and curator Andrea M. Delph will present the series at Living Room Contemporary in Brooklyn. Ahead of the exhibition, we spoke to Walters about her incredibly honest and brave work. “I have learned there is a power that comes with telling your story,” she says in the following interview. “There is a comfort in doing so too.”

Your new series is the “second wave” in your healing process after being raped. What was the first wave? How did you first start to heal yourself?

After being confronted with past sexual trauma in late 2016, I became paranoid around men. I didn’t like being in Ubers with male drivers or passengers. I didn’t like being in public with men. I suddenly didn’t feel comfortable around my guy friends, even some of my best friends. I finally was aware how unsafe I felt around men. In 2017, I began Boys in the Front Seat, a photo series and documentary where I shot 20 Black men in the front seat of my car. It explored emotions, masculinity, and the power dynamics between women and men in relationships. Boys was the start to rebuilding trust and healthy relationships with men while better understanding them. After telling my story to my ex-boyfriend and him not believing me, I was scared to tell other men what happened to me. I didn’t want to be looked at as “damaged goods” or this woman who “came with too much.” In Boys, all the men in the series were friends of mine and offered nothing but love and support after [I told them] my story. Their vulnerability and openness with the series and myself restored my love for Black men. That series made me comfortable talking about being raped and moving forward from that.

How did you come up with the idea for The Self-Portrait Series ? Was the intention for the project to be healing or did you discover that it was healing after it began?

I started shooting The Self-Portrait Series in January 2018. I had no idea why I was shooting myself in these locations, but I knew I couldn’t stop. Shooting myself was challenging, yet felt natural for me. It was fun and therapeutic. It wasn’t until the photos were developed from the eighth location that I started to get a sense of what I was doing. There was this one particular photo I saw that I couldn’t stop looking at. It was is my silhouette in this cave filled with light and darkness. When I saw that photo I cried for hours. That was the first time I really saw myself even though I had been shooting myself for months. Everything began to make sense. After being raped in 2013, I avoided photos and my own reflection for almost five years. This series was my way of moving forward and finally having the courage to face who I am and who I became after my body was violated. Everything I had been searching for was already within me.

Why did you want to appear naked in some of the photos? Was this a way to reclaim your body and sexuality?

After I was raped, I didn’t feel like my body belonged to me. It’s been an intense healing process for me to finally begin to feel like it does [belong to me]. I have found that we constantly shame our bodies, from how they look to what has been done to them, with consent or without. I think the nakedness in these photos displays the freedom I have found within my body and the love I have developed for it through this series. I also admired how artists like Carrie Mae Weems and Ana Mendieta displayed their naked bodies in their art. I saw their level of vulnerability and confidence, and [how they] proclaimed a space that is rightfully theirs. I wanted to feel that and better understand it. One day, I caught myself running butt-ass naked in a desert. It felt natural!

The majority of rapes are never reported, but of those that are, 80 percent are reported by white women. Why do you think women of color are less likely to report being raped?

I think any woman, regardless of color, is faced with being accused as a “liar,” or “attention seeker.” Women who have been raped have to constantly explain their story in such a way that makes others believe it wasn’t their fault. We are constantly being questioned as if it is. So I completely understand why women don’t speak up about it. I think, as women, we are terrified about the aftermath of coming forward, especially [about] how you’re perceived professionally .

In particular, women of color are dealing with generations of sexual trauma and a history of patriarchy that has stood by silence instead of truth. We come from a long line of not talking about the traumatic things that have happened to our bodies, our families, and our people. I know in Black families, we aren’t brought up to talk about our feelings. There is a myth that strength comes from silence, when I have found my strength comes from using my voice and defying that belief.

Do you hope that your work will encourage other women to speak out?

I do. I am working on starting a conversation about it. I hope my art helps girls and women realize how common sexual trauma is amongst us. Too many of us have been through it, including men, and I hope we get to a place where we can talk about it and remove the shame associated with these experiences in a healthy and healing way. I have learned there is a power that comes with telling your story. There is a comfort in doing so too.

What is something that would like to share with other survivors?

Healing is an everyday process. Take your time with your process. We are unpacking centuries of trauma. I am still healing. I have great days and I have dark days, but always remember: You matter and your story matters. Speech is the most powerful gift we have been given, and through it, we all can find the freedom we’ve longed for.