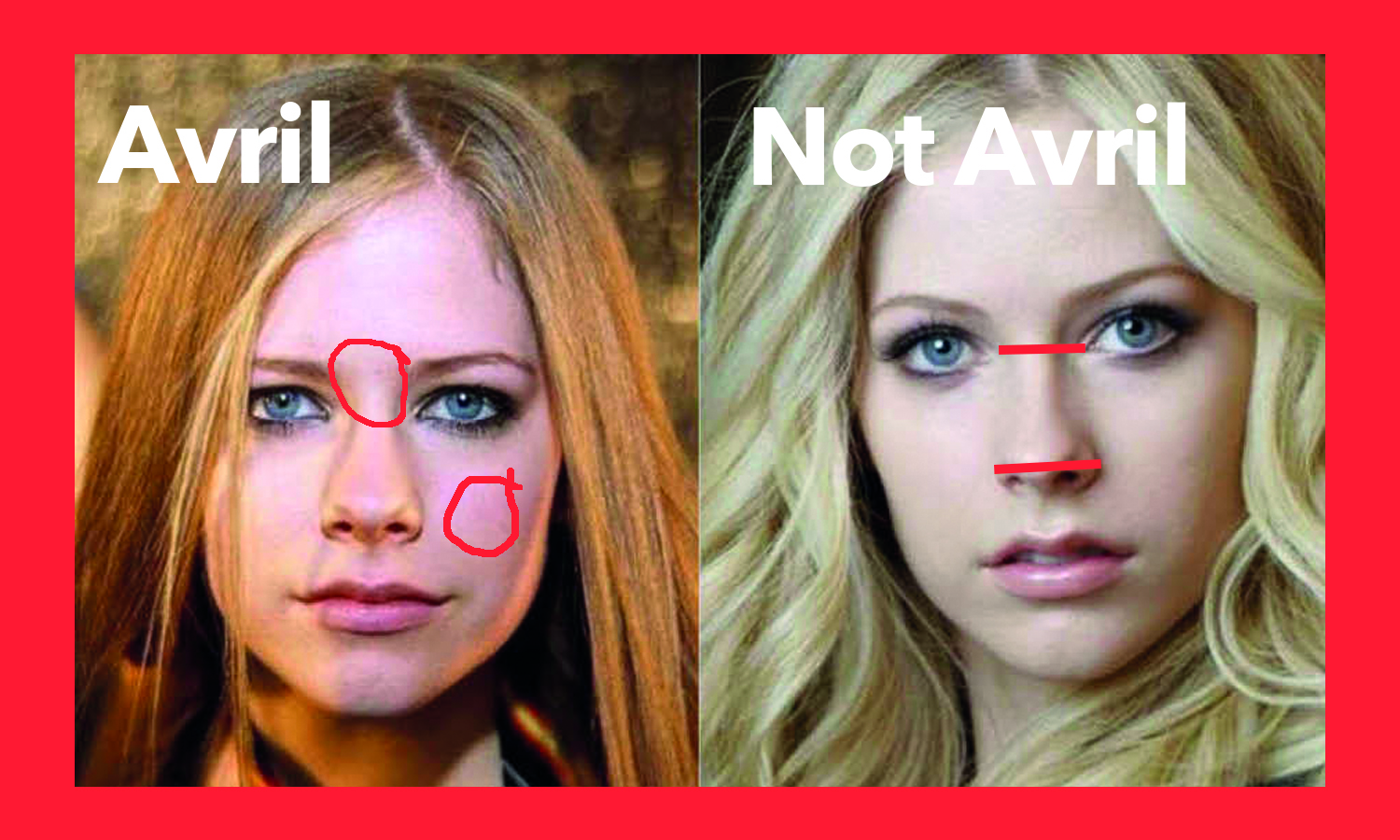

You may not buy any of the conspiracy theories out there about faked moon landings and inside plots to murder Princess Diana, but the chances are you’ve probably invested in at least one completely outlandish story about a celebrity. From the claim that Avril Lavigne died in 2003 and was replaced with a lookalike named Melissa, to the bizarre proposal that Nicolas Cage is a vampire from Victorian times, the wilder the theory, the more people subscribe to it; or at least entertain the narrative. So long as there’s a scrap of dubious evidence out there — in Avril’s case theorists spent hours circling various freckles and analysing her body language in search of tiny differences — the conspiracy is fair game.

Conspiracy theories have been all over the news recently for more sinister reasons; in part thanks to a former Campbell’s Soup executive who falsely claimed that the company’s CEO, George Soros, was secretly providing aid and provisions to the refugees travelling towards the USA in the so-called “migrant caravan”. There are various other well-known conspiracies out there which don’t get much serious air time: 9/11 being an inside job, for example. Most people dismiss these hypothetical plots immediately; writing it off as pure delusion, or — in the case of the Soros conspiracy — deliberate lies spread with the intention of stirring up hate and unrest among those that are susceptible.

And yet, when it comes to secret gay relationships between singers in globally successful boy bands, cloned popstars, and murdered eighth members lingering as ghostly spectres in photos of the K-Pop group BTS, we’re hooked. I’m not above it, either — in fact I’ve spent entire mornings meticulously combing through this detailed Powerpoint presentation about how Lorde’s latest album, Melodrama, contains hundreds of highly unlikely clues about an affair with producer Jack Antonoff, behind his ex-girlfriend Lena Dunham’s back. Whether the speculation amounts to anything factual hardly matters, and frequently celebrity theories themselves are steeped in irony. Their authors likely know full well that Lorde did not directly cause Trump’s election because her affair distracted Lena Dunham from working on Hillary Clinton’s campaign, just as they’re fully aware that Taylor Swift is not really the satanist Zeena LaVey. Instead, perhaps it’s just fun to suspend our disbelief for a second, and make an entertaining comment about the strange world we live in.

“The world is a complex place,” Dr. Daniel Jolley, a senior lecturer in psychology at Staffordshire University, says. “We have many different demands, so our brain has developed cognitive shortcuts. This allows us to respond quickly — but a drawback is that this can’t always work in our favour,” he continues, explaining why the human brain is so drawn towards the concept of conspiracy in the first place. “One cognitive shortcut — or cognitive bias — is proportionality bias. This is where we believe a significantly large event must be explained by something equally as large.” He gives the example of Princess Diana. In reality the royal was killed in a random unfortunate accident; a car crash that took place in a Paris tunnel.

However, a widespread conspiracy theory also exists which posits that her death is a massive conspiracy by the UK Government. In the years following Diana’s death in 1997, the Met Police even launched an enquiry — Operation Paget – to investigate if these conspiracies had any real substance or grounding. After years of investigation, they disproved 175 different theories about the accident.

“When a big event happens, our brains are drawn to make this connection; big event equals big cause!” Dr. Jolley says. “This is just one example of a cognitive bias that we have.”

In the case of well-known public figures like celebrities, he adds, this proportionality bias especially applies. “With celebrities, they are naturally going to spark attention because they are well-known people, who people may be likely to make proportionality bias connections with,” he points out.

“Conspiracy theories are definitely appealing because they are controversial and entertaining,” Dr. Jolley says. “Feeling like you have unique knowledge that sets you apart from others can be something that is appealing for some people.”

It’s also a fact that celebrities’ lives often verge on parody anyway . Remember when we all looked on in disgust as Kim Kardashian spent $1,500 on a ‘vampire face mask’ made from blood? When Gwyneth Paltrow began preaching about the healing benefits of vagina steaming? When Barbra Streisand cloned her dead dog, Samantha, and then took the clones to visit their creator’s grave? Exactly. Perhaps that Avril clone theory isn’t so outlandish after all.

“I think this is absolutely the case,” agrees Julia, a self-confessed obsessive who believes that the ridiculousness of famous peoples’ lives only adds to the draw. ”Particularly with theories such as Britney Spears being on The White House payroll: [people claimed] she would do something crazy whenever there was a mess up [in Bush’s government] to get everyone talking about something else. Britney’s life was wild, and the whole industry is totally messed up,” Julia adds, “so if some of them were true I honestly wouldn’t be surprised.”

“The claim that Beyoncé wore a prosthetic stomach in order to fake her first pregnancy, for example, doesn’t involve any kind of sinister global plot. Instead, it says more about how we react to women’s sexuality.”

And Chloe — another enthusiast whose favourite theory is the idea that Taylor Swift is a ‘beard for hire’, paid to dispel gay rumours surrounding famous young men — reckons that the elusive nature of public figures also contributes to the appeal. “A lot of these celebs are so private and guarded about their personal lives. When you’re in this deep in their specific fandom (or just celeb obsessed in general) it’s only natural you’d want to fill in the gaps with your own imagination.”

“It also helps if the celebrity is seemingly a ‘normal’ celebrity who doesn’t have crazy stories attached to them already,” Julia tells me. “Also, lots of evidence makes me love a theory more — particularly pictorial and video, as it makes it seem so much more convincing. I love to see the hard work someone has put in to convince you.”

The advent of social media plays a part in the popularity of theories that would’ve previously remained consigned to niche forums. For one, bizarre alternative narratives about celebrities circulate more quickly than ever, in the form of detailed Twitter threads, YouTube videos, and in depth evidence files like this Harry Louis Treatise on Tumblr. Thanks to the internet, it’s now completely possible to comb hundreds of photographs of Avril Lavigne online, circling individual freckles in the hope of proving that she’s actually being played by a look-alike, just as it’s now easy to scour through a famous person’s recent ‘likes’ and comments on Instagram in search of clues. No matter how outlandish a theory is, there’s a decent chance that there’s at least some potential supporting evidence available in a few clicks.

“A lot of the time you do think ‘that can’t possibly be true’,” Julia agrees. “The entertainment of the Twitter thread that followed [the Avril Lavigne theory] was spectacular and thoroughly enjoyable to read through. I don’t think there’s any real harm in it — unless it’s really gross and disturbing and could potentially affect their life.”

While conspiracy theories have traditionally been associated with huge world events, many of the stories spun around celebrities are relatively minor. The claim that Beyoncé wore a prosthetic stomach in order to fake her first pregnancy, for example, doesn’t involve any kind of sinister global plot. Instead, it says more about how we react to women’s sexuality. Maybe, for some people, it’s easier to accept a conspiracy than the idea that a perfect, flawless pop star had sex, and then carried a baby. Let’s face it, few people can easily picture a heavily pregnant Beyoncé yelling at Jay-Z because she’s craving Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, anyway. Perhaps fake pregnancy theories are common for this very reason — a real pregnancy would shatter the illusion.

Think of harmful conspiracy with visible real-world effects — the concept of ‘fake news’, or the especially disturbing theory that Emma Gonzalez, the Florida student who spoke out following the Parkland school shootings, is a hired ‘crisis actor’ — and they all share one thing in common. They serve the purpose of bending thinking towards a specific political leaning or ideology; if theorists can spin a narrative in order to reinforce a belief they hold about the world, it validates these beliefs. Where people don’t see their beliefs represented in the mainstream, they craft their own outlets instead, and accuse the mainstream of having a corrupt agenda.

Though casual speculation about Taylor Swift’s supposed long-term relationship with Karlie Kloss, for instance, is a theory that’s unlikely to cause tangible damage, it also comes from a similar place. By conducting a narrative in which one of the world’s biggest stars might be LGBTQ, queer representation appears where there was very little. And while most rational people realise that the ‘fake news’ movement sweeping the world is a dangerous threat, or that bizarre speculation around 9/11 is deeply concerning, imagined scandals involving our favourite celebs are considered fully up for grabs.

While it is true that most celebrity conspiracy theories are relatively harmless — Justin Bieber, for instance, probably isn’t worried by the idea that some people think he’s a shape-shifting reptile — there is clearly a line. The conspiracy that JonBenét Ramsey (a child beauty queen who was brutally murdered in 1996) was never killed and in fact grew up to become Katy Perry is one theory in poor taste. And in the case of ‘Larry shippers’ — who believe that One Direction members Louis Tomlinson and Harry Styles are in a gay relationship — their constant search for evidence did have real-world repercussions. “When [the conspiracy] first came around I was with [girlfriend] Eleanor, [Calder] and it actually felt a little bit disrespectful,” Louis told The Sun. “I’m so protective over things like that, about the people I love. So it created this atmosphere between the two of us where everyone was looking into everything we did,” he said of his friendship with Styles.

According to Dr. Daniel Jolley, who researches into the significant and detrimental consequences that conspiracy theories can have across political systems, it’s important not to get too caught up. “In isolation, subscribing to a celebrity conspiracy theory — e.g. that Beyoncé is a robot – is unlikely to have a big impact on the individual or wider society,” he says. “However, conspiracy theories can actually increase mistrust, uncertainty and powerlessness — if people have conspired about this event, could they have conspired about other events? This may start a circle of questioning around another aspect of life, such as whether climate change is a hoax and if vaccines are safe. We know from research that — for example — being exposed to the idea that climate change is a hoax can reduce people’s likelihood of reducing their carbon footprint,” Dr. Jolley says. “This can not only impact the individual, but wider society. Conspiracy theories can impact people in significant ways.”

In other words, it’s relatively harmless to concoct ridiculous narratives about celebrities. Just ensure that they stay consigned to the realm of fiction.