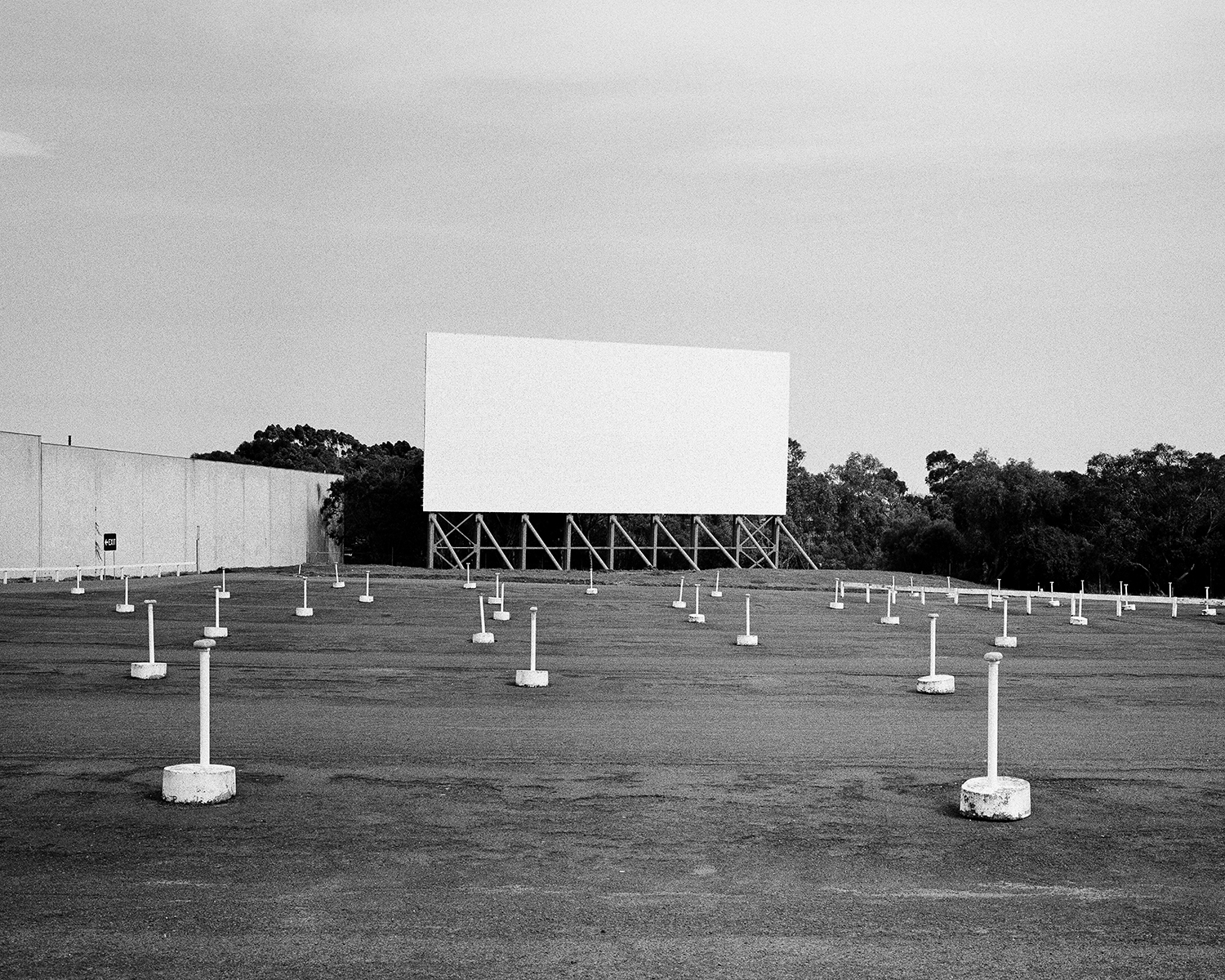

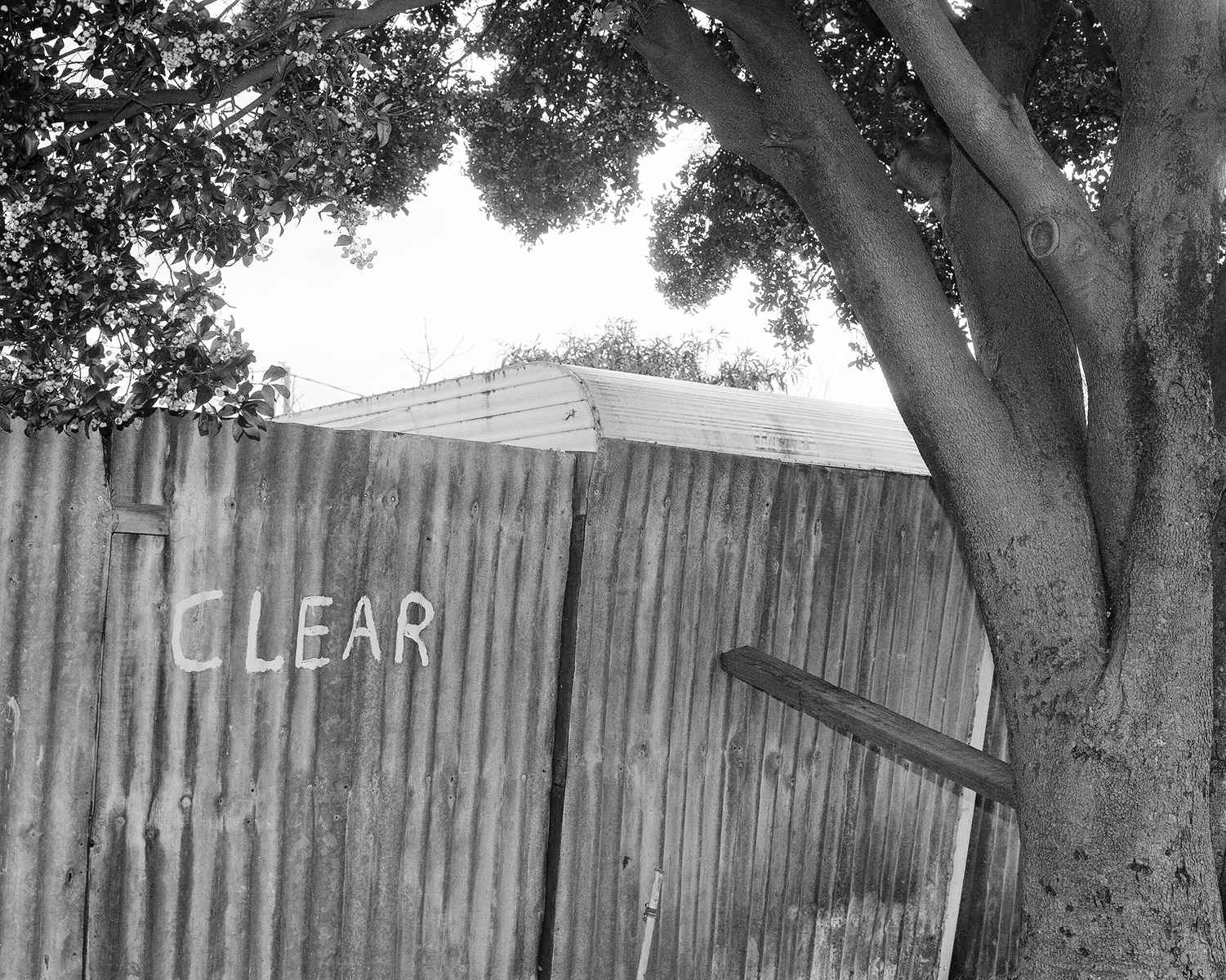

Mitch Pinney discovered photography while growing up in Byron Bay through his desire to document punk shows and his friend’s bands. In the years since Mitch developed a thoughtful yet candid style with a DIY work ethic, releasing a slew of self-published books and zines along the way. His new book It’s Just A Place To Stand features a series of black and white photographs of friends and strangers set amongst an inner-suburban backdrop. We caught up with Mitch to talk about his new work, the ambiguity of shooting in black and white, and his unforced approach to photography.

Why did you name your book It’s Just A Place To Stand ?

It’s Just a Place to Stand is talking about how photography works — like you’re standing in one place and you’re experiencing this thing in front of you. And then, that’s kind of all it is. That’s how I like to shoot. I think that’s why I struggled at university, because I only really liked to take photos of circumstances that I found myself in. I find it really hard to come up with good concepts prior to taking the photos.

I read that Lee Friedlander was once talking about how students don’t take photographs to take photographs anymore. They all have to have a concept they’re working on, or a problem that they’re dealing with in society. In an interview he was saying he has a photo series all about monuments — and didn’t know he was making that series until he’d taken all of these photos. He would shoot haphazardly, then he would look through all the things that peaked his interest and just be like, ‘Oh, I like this thing’ or ‘I am interested in this thing’. And it’s like a way of pulling yourself apart I suppose. That’s sort of the way I like to do it.

The book is entirely black and white, do you generally shoot that way?

I feel like I made a decision that I was just going to shoot black and white for a little while, and I haven’t been able to shake it off yet. I mean it is cheaper, and you can develop it yourself which is a bonus. But other than that it makes it a little bit more floaty, in the sense that there is no indication of when the photos were taken. The timelessness of it, as if it could’ve been shot in the 70s, 80s, 90s, or right now or twenty years from now. I think I really like that.

Your book got picked up by Perimeter, how did they get involved?

I printed it all myself, Perimeter just took them on consignment because it was all self-published and self-released. I guess they liked it. I’ve been going to their store for a few years now, I’ve gotten to know Dan a little bit, and we always have a nice little chat. He’ll always ask me what I’m up to and what I’m working on. They’re great, also very good for the photo community I think, because they’re accessible, or, for me I guess anyway. I feel like I could just send them an email and just be like ‘hey’, you know? I think they push the broader community to be better as a whole, I’d say.

Who are the major influences of your work?

One of the first photographers I got into was Glenny Friedman. He was a skate photographer and punk photographer who has a book titled Fuck You Heroes. I got really into him first, probably when I was sixteen and I just thought it was amazing. It’s always been a pretty deep part of my identity I think. I’ve always been going to punk shows, and taking photos of what I saw there. I mean it was the reason I even got a camera to start with, because I wanted to take photos at shows and document my friends bands and stuff.

How did growing up in Byron Bay inform your work as a photographer?

Growing up in Byron there weren’t that many people who were into photography. I remember having to go on forums to find my first camera, I got a 5D Mark II for my 18th birthday and that was a pretty big thing for me. But then I was just using that and I couldn’t figure it out. Like “how did they get the photos to look this certain way?” I spent months trying to figure out what filters they were putting over their photos and then one day I figured out it was medium format film. I didn’t think film could be good because the only photos I knew of as film were the photos you saw in your family photo albums, or the disposable point and shoot cameras. I didn’t realise you could have these beautiful, super high definition large format photographs.

Where do you think your current headspace will take you next?

I’d like to slowly build something again. I must admit, I’m not in a huge rush. I like being in my bedroom and having the feeling of making something — it’s the nicest part. I haven’t had a solo photo exhibition before, because the idea of it is… I don’t really get the concept of an exhibition, it’s kind of weird to me [laughs]. It’s like, you have to spend way more money, you have to hire the gallery space, get your work printed, get the frames made, all of the promotional material, all of that bullshit, and then you take it down a week later.

Also, another reason I don’t like exhibitions — how much does a picture like one of mine go for? How many people can actually afford that versus my book, which I sold for thirty dollars.

Mitch Pinney’s ‘It’s Just a Place to Stand’ is available from Perimeter.