“Is it possible in this age of publicity for a photographer to be both famous and obscure at the same time?” New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer asked of Evelyn Hofer (1922–2009) in a 1982 exhibition review. Whatever the answer, Hilton realised something was amiss. Evelyn, who had once worked with Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar and collaborated with celebrated writers like Mary McCarthy, V. S. Pritchett, and trans pioneer Jan Morris, was still a figure on the fringe.

“Miss Hofer is regarded as one of the most illustrious of living photographers, and her work has inspired an interest that amounts to a cult,” Hilton continued. Alas, these circles do not include the museum world, where reputations in photography tend nowadays to be made. At the Museum of Modern Art, for example, not only has she never had an exhibition — she seems not even to have been heard of.”

It is only now, more than a decade after her death, that her life and legacy take centre stage in the new travelling exhibition and forthcoming book, Evelyn Hofer: Eyes on the City. Bringing together 100 vintage prints, the book showcases work from her seminal photography books, which include The Stones of Florence (1959), London Perceived (1962), New York Proclaimed (1965), The Evidence of Washington (1966), and Dublin: A Portrait (1967).

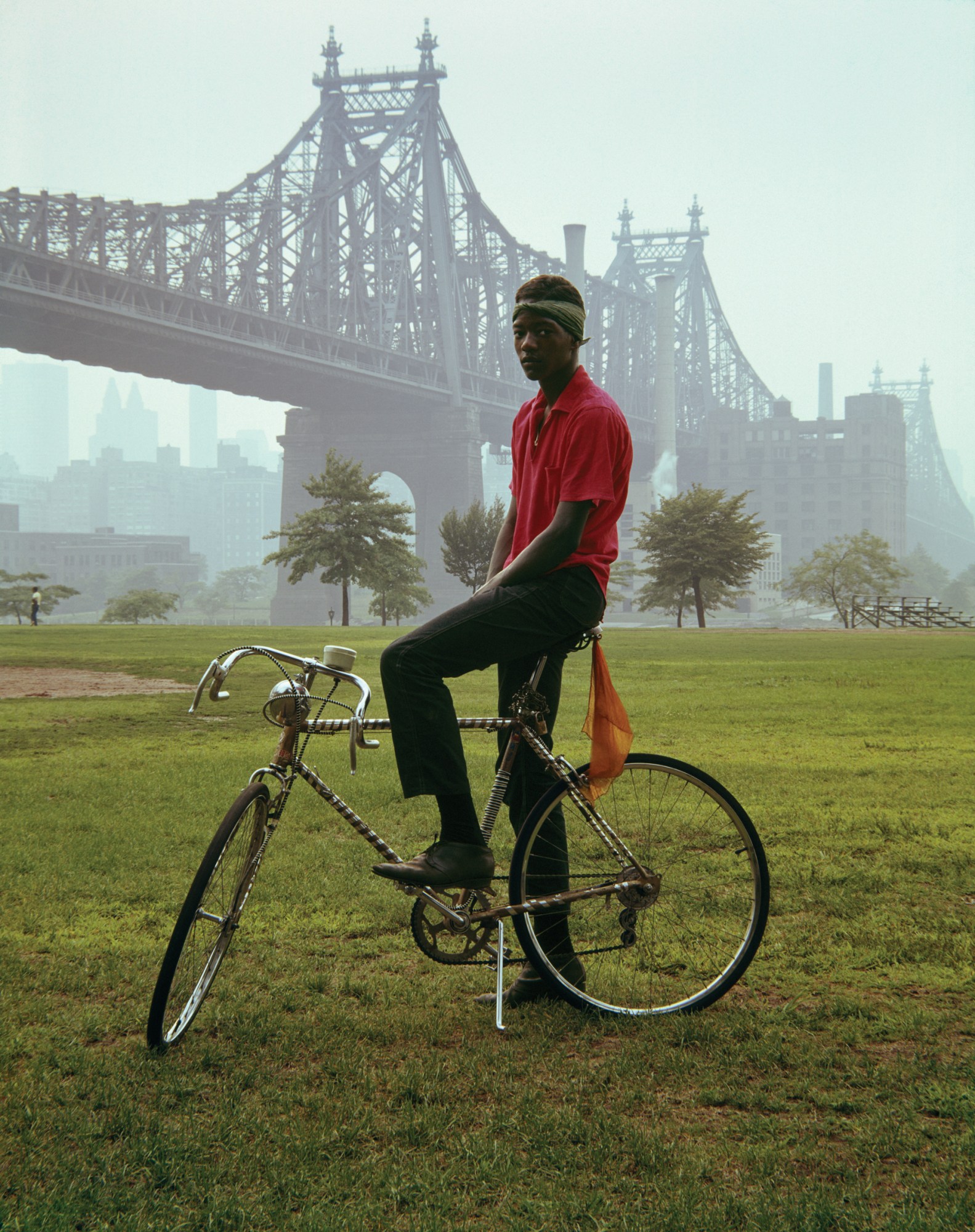

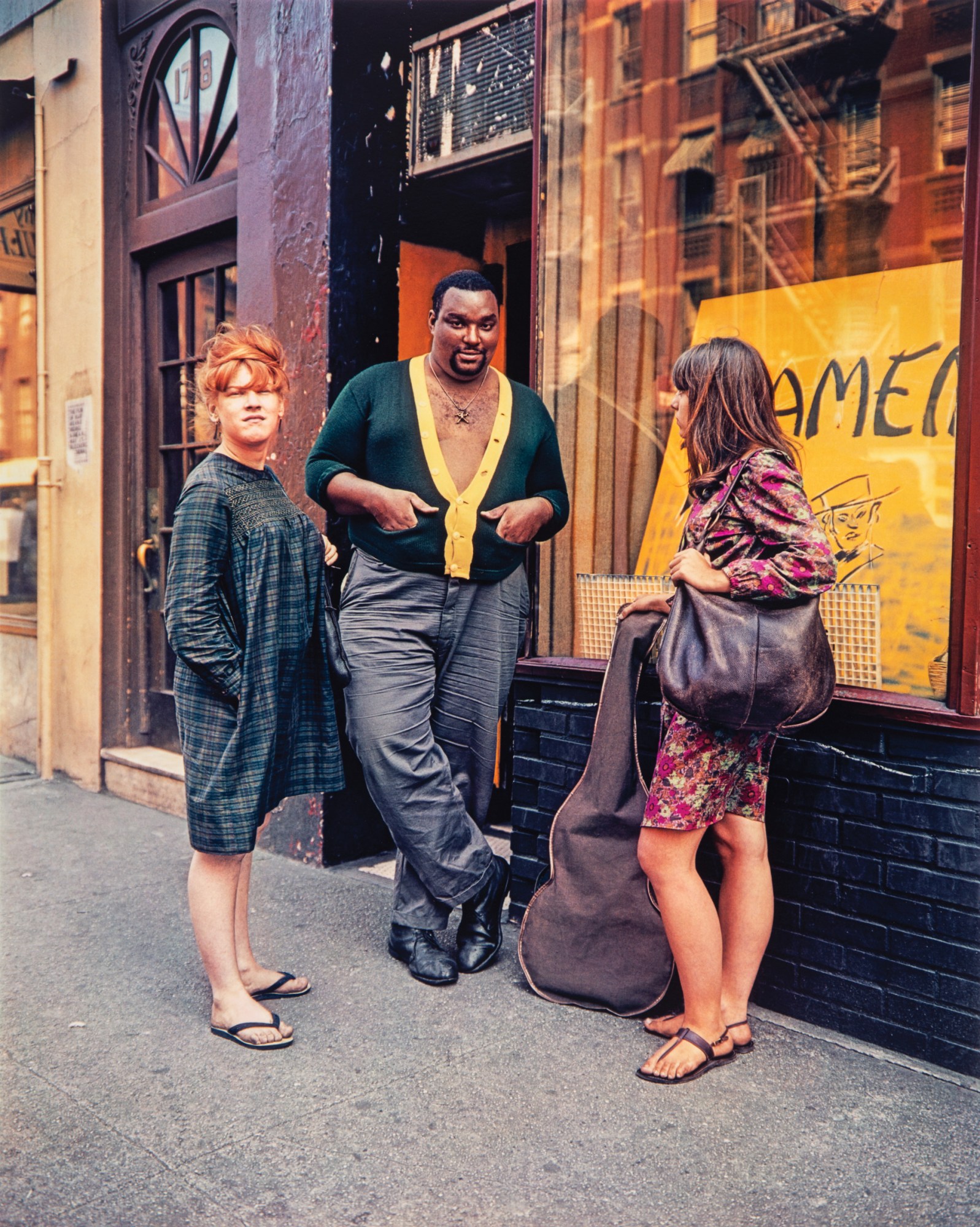

Searching for the transcendent resplendence of the mundane, the mystical truth of place that allows viewers to feel as though they are there, Evelyn elevated scenes of the everyday to the realm of fine art. Using a 4×5 view camera, she crafted majestic large format portraits as a painter would to create timeless photographs of Florence, Dublin, New York, London, Spain, and Washington, D.C.

“Evelyn was doing the anti-avant garde,” says Gregory Harris, who co-curated Eyes on the City with April Watson. “She was making pictures at a time of great social change and political upheaval. I think she’s grappling with a world that’s in flux and being renegotiated in the 60s. A lot of things were up for grabs like, where do we live? Who gets to live? Where, how do we talk about identity and equity? She’s trying to work through similar things without kind of coming at those issues head on.”

From a young age, Evelyn had to grapple with the impact of tectonic shifts in her native Germany. After the Nazi Party took control 1933, Evelyn’s family moved to Geneva, and then Madrid until Franco came to power. Realising it was time to leave the continent behind, Evelyn’s fervently anti-fascist father brought the family to Mexico City, where Evelyn got her start as a professional photographer in the early 40s.

Seeking greater opportunities, Evelyn moved to New York to work in the city’s flourishing media industry. Picture magazines were in their prime, promising all the pleasure and spectacle of a Hollywood film. Evelyn began working for both Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, her work published alongside Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Lillian Bassman. But fashion photography was not the right fit. “I was terrified by those sittings, and didn’t like the restrictions. I wanted to take photographs only for myself,” Evelyn said in 1981.

Using the principles of the New Objectivity movement (a style that challenged Expressionism and favoured unsentimental reality) Evelyn embraced the magic and mystery of the unadorned world as it unfolded before her camera, like a scene from a play. Immersed in the explosive post-war New York art scene, Evelyn surrounded herself artists like Andy Warhol, Hans Namuth, Richard Lindner, and Saul Steinberg, and began applying the eye of a painter to her experiments in colour street photography and street portraiture.

In 1957, Evelyn met American novelist and critic Mary McCarthy, who was in the process of transforming her New Yorker serial on Florence, Italy, into a lavishly illustrated coffee table book. Together they set forth on a collaboration that would form the blueprint for Evelyn’s most significant contribution to the form: the timeless art of photography books.

Walking the streets of Florence getting to know the local landscape, Evelyn discovered what she had been searching for: a slow, immersive approach to environmental portraiture that allowed her to distill the timeless spirit of a people and place. “I wanted to try to capture the quintessence of the city —that something which has nothing to do with our times, the present, or the future,” she told US Camera in 1961.

In every city travelled, Evelyn saw the beauty and nobility of the people she encountered on the streets perfectly aligned with the great treasures of art history. This is particularly evident in her photographs in New York and D.C., where Evelyn devoted extensive time to chronicling Black life during a time of radical change.

“Evelyn was making these pictures at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, so there were a lot of images of Black Americans in the media, but for the most part they tended to either fetishise poverty and disenfranchisement or they were very violent images of protests, civil disobedience, and resistance,” Gregory says. “There wasn’t a lot of middle ground so I think she was she was purposefully trying to tell a more nuanced story. She didn’t write or speak too much about this but it comes through in the work.”

Throughout her career, Evelyn remained uncompromising in her vision, never forsaking her principles for the sake of status, wealth, or fame. Instead, she remained true to her path — one few walked then, or now.

‘Evelyn Hofer: Eyes on the City’ is on view through 16 August 2023 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The exhibition will then move to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City (16 September 2023 – 11 February 2024). The catalogue will be published on 4 July 2023, by Demonico/High Museum of Art/Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Credits

All images © Estate of Evelyn Hofer