“At first glance, Guy Bourdin is not an artist with whom I have a lot in common,” confesses Giorgio Armani, who has picked 100 works from the revolutionary oeuvre of the French fashion photographer, who died in 1991, for the latest show at Milan’s Armani/Silos. “A sense of provocation is immediately evident in his work but what strikes me the most — and what I wanted to focus on — is instead his creative freedom, his narrative skill and his great love of cinema.”

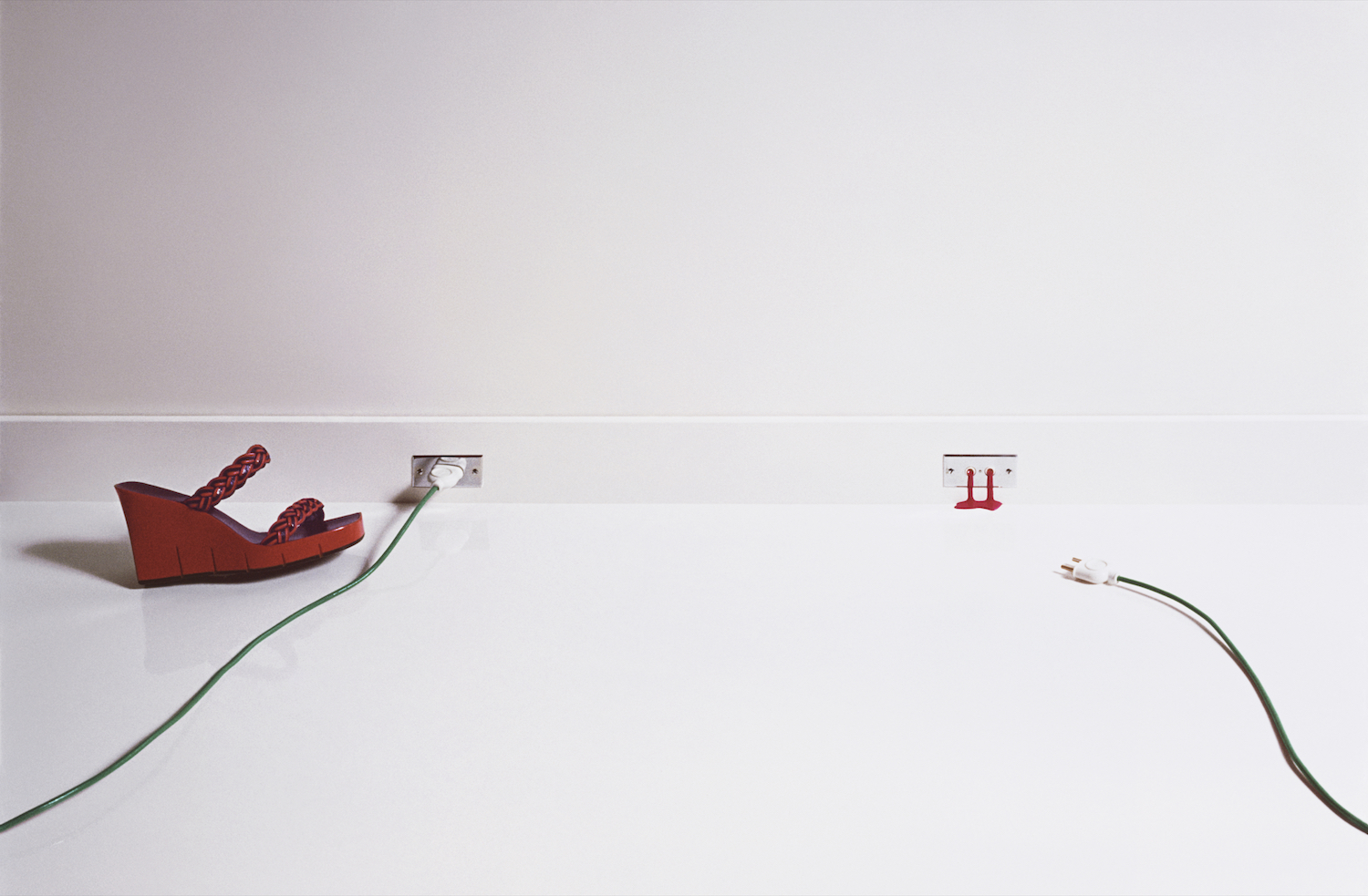

Guy told stories — delicious, disquieting ones which leave room for the imagination. “He was one of the first storytellers in the history of fashion photography,” says Shelly Verthime, the long-time curator of Guy’s work. “Half-told and full of implication, the narratives in Guy’s photographs are not easily decipherable, so you’re left wondering what has happened or what might yet happen.” Across the austere greige walls of Armani/Silos, you really see Guy’s mercurial creative spirit at work — and play. We are dealing with fictions — self-fashioned, self-dramatised stories which have a particular way of lodging themselves into your psyche. They taunt because they’re all about what’s left unsaid. Guy’s message to you was wrapped with a wink and a hint.

Here, we speak with Shelly about his jaw-dropping work.

What do we know about Guy’s childhood?

Guy was born in Paris in 1928 as an illegitimate child, abandoned by his mother and later adopted by his father. Little information about his early years exists, but what we do know is that he had a deep interest in art and turned to drawing as a source of comfort during his solitary childhood. After completing military service in 1950, where he gained his initial exposure to photography, he returned to Paris.

In the introduction to the catalogue of Guy’s first show in 1952, Man Ray wrote: “I can tell you that Guy Bourdin is trying with all his heart to be more than a good photographer.” How did they meet?

Guy knocked on Man Ray’s door several times only to be shooed away. Finally, he was allowed into the studio, where he was exposed to Man Ray’s fantasy of “high art”. Man Ray represented, for Guy, a Surrealist who was experimenting with the relationship between storytelling and the emotional psyche in a way that suited his unorthodox interests. Even in his early 20s, Guy was adamant that he needed total creative freedom. With the few words he penned in that catalogue, Man Ray envisioned the future of the young and passionate Guy Bourdin.

Mr Armani’s selection focuses on “storytelling”. Guy was fascinated by cinema, right?

Yes, particularly psychological thrillers. Towards the end of the 60s, he began using his images as voyeuristic canvases, echoing B-movie intrigue and suspense. Guy was as much a master of light and shadow as he was of colour. Yet, as Nick Knight has said, his work isn’t just visually stunning but thought-provoking too. Take, for instance, his iconic umbrella scene, which leaves us with an incomplete but fascinating narrative. Is the woman running away? Who is chasing her? It was originally published as a makeup ad, but Guy religiously prized the photograph over the product. In the pre-digital era, one can only imagine the countless hours it took to compose this shot, with its 40 shades of black.

What was Guy’s working method like?

Guy was first and foremost an artist. Throughout his life, he drew and painted, developing a practice that extended into the studio. There, as his assistants recalled, he sketched out his ideas in his famous Rhodia notepads. He was a relentless perfectionist, involved in every aspect of his photoshoots, from crafting the sets to supervising hair and makeup in the “Bourdinesque” style. He insisted on complete artistic control and was known for submitting a sole photograph to the picture desk, cropped only by him.

Guy’s 1955 debut in French Vogue pictured a model sporting the creations of milliner Claude Saint Cyr beneath three tongue-sucking cow heads. From there, how did he make the medium of magazines his own?

That editorial was far from standard Vogue fare, yet it inaugurated a three-decade-long relationship with Condé Nast. Guy was the only photographer who dared to stage such intriguing scenarios for the fashion world — and whose clients and editors allowed him the liberty to do so. Francine Crescent, French Vogue’s long-time Editor-in-Chief, never refused a photograph.

In the 60s and 70s, fashion magazines underwent a dynamic transformation, and French Vogue was leading the line. Guy’s editorials towards the end of the 70s were truly exceptional, with some spreads spanning up to 20 pages. One of his most ground breaking innovations was his use of the double spread and the centrefold, through which he incorporated the mirror motif so beloved by the Surrealists. This unique visual identity really set him apart from his contemporaries.

In what ways did Guy embody the bold, boundary-breaking spirit of the 70s?

This was an era marked by youth revolutions, political upheaval and shifts in social values. Fashion, in turn, drew on a diverse range of visual iconography, including Pop Art, Hollywood glamour and space-age chic. Guy’s work was reflective of this creative melting pot. It exuded a strong, ultra-femininity and confident, urban sophistication. His edgy glamour, dark humour and rich sensuality unsettled even the most privileged of audiences. Yet it should also be remembered that, although Guy embodied the social change occurring at the time, he always remained true to his personal vision — ever witty and sharp.

You were involved in the curation of the first-ever institutional Guy Bourdin exhibition at the V&A, 20 years ago. What was that like?

At that time, fashion photography was rarely exhibited in art museums. The emphasis was obviously on the fashion work, but we also showcased Guy’s vintage prints, films, Polaroids and sketches. The exhibition became a mecca for designers and students, the young generation and the old guard alike. Guy was considered a cult photographer when I started my research over 20 years ago. Only over time, as I began unveiling most of his personal photography, was I able to connect the dots and present everything as a coherent body of work.

Guy’s biography has been riddled with rumours, leading many critics to dissect him in a Freudian manner. Why do you think this is?

Although Guy reached the highest pedestal in fashion photography, he remains, until today, an enigma. One of his long-time collaborators at Vogue said that he wanted to remove every trace of his life. The transient magazine page perfectly reflected the public persona Guy projected. He shied away from the limelight, never accepted interviews, nor consented to having his portrait in Vogue’s celebrity spreads. When I reached a stage in my research where I thought it would be a good idea to interview some of Guy’s collaborators, it was his late son, Samuel, who wisely imparted: “Look at the images. Everything is there.” And that is what I did.

How did this journey begin?

After two years of chasing Samuel, I finally met him in Paris in the home of Alber Elbaz, with whom I was working for years. Samuel was heading off to Milan to print the first Guy Bourdin book, Exhibit A, and arrived crushed after a long flight from Brazil. I couldn’t see his eyes through his sunglasses, but I sensed what his first question would be. His father was very much into astrology and would ask every model what their star sign was…

“Scorpio,” I replied. “Hmmm… My daughter, Leah, is a Scorpio as well… What date?” asked Samuel. “17 November,” I replied. “The same as Leah,” said Samuel. In the corner of my eye, I saw Alber “sinking” into his chair. For Samuel and I, it marked our first bonding. Not long after, he showed me his mother’s wedding ring, inscribed with the same date. Coincidences…

What role did Samuel play in his father’s legacy?

Samuel was 24 when Guy passed away. With all the grief of loss and being totally alone, it took him nearly a decade to officially inherit the estate and begin archiving the material. Throughout his life, until his unfortunate death last year, Samuel carried the legacy of his father with incredible integrity and compassion. He chose to live a simple life, dedicating himself to the guarding of the Estate.

So, when does fashion photography become art?

Today, the lines between art, fashion and photography are constantly evolving. However, if fashion photography is to be considered a true art form, it should be evaluated on its influence and its ability to capture the spirit of an era. In this regard, I believe Guy Bourdin deserves recognition as an artist more than most.

‘Guy Bourdin: Storyteller’ runs at Armani/Silos, Milan until 31 August 2023.

Credits

All images © The Guy Bourdin Estate 2023. Courtesy of Louise Alexander Gallery