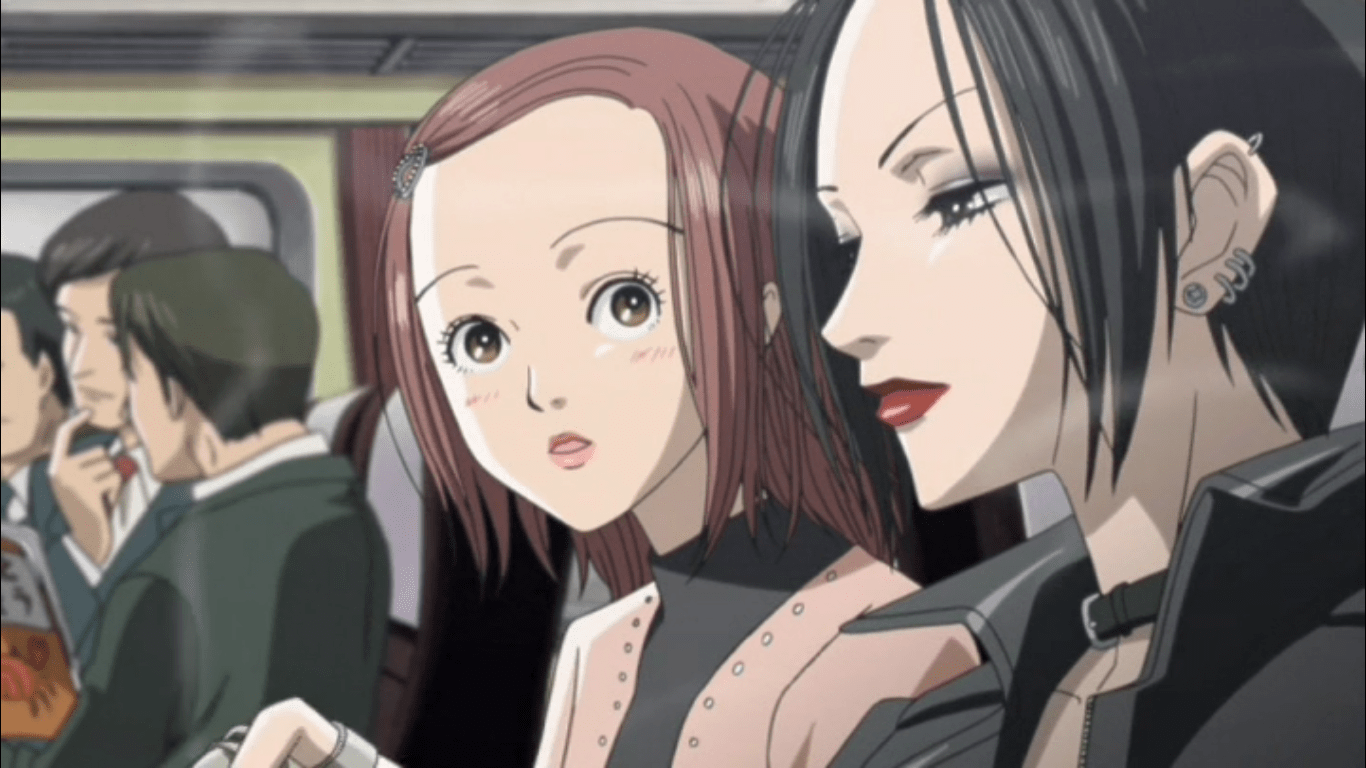

At the turn of the millennium, Japanese artist Ai Yazawa introduced the original goth girlfriend: 21-year-old punk Nana Osaki graced the pages of serialized shōjo and josei manga magazines (young female-aimed publications) as the protagonist of Nana. Each new issue following Osaki’s starry-eyed fantasy of rising to musical stardom in early-2000s Tokyo, a colorful metropolis of rejected demo CDs and bleached ganguro girls. Amongst her surroundings, Osaki was a beautiful anomaly with her unkempt black bob, smudgy eyeshadow, and wine-hued lipstick that would put Met Gala Grimes to shame, while her wardrobe epitomized stylish intrigue a la Vivienne Westwood or late-90s riot grrrl. And though her artistic dreams were seemingly too ambitious, by the end of Yazawa’s manga-turned-anime series, Osaki’s inimitable image eventually captivated all of Japan. Indeed, the small-town girl with a provocative aesthetic and too much emotional baggage rose to nationwide fame as the frontwoman of Japan’s biggest rock band.

But on a more intimate and nostalgic level, Osaki portrayed the kind of misfit chick that would scare assimilating yet inspired real-life teenagers – those fanatical about balancing their outward self-expression with social acceptance – into an envious and observant silence. Born and raised in the banal suburbs, I was one of those many young, confused baby millennials stuck in a place where uniformity equated to social acceptance. Contrary to what 80s teen flicks starring Molly Ringwald illustrated, there wasn’t always an eternally present clique distinct from the normie culture that my past self or surroundings represented. And with the absence of creative-looking peers serving as firsthand fashion inspiration, many of us harboring the desire to present uniquely had to depend on artful media to fuel our own creative minds. For millennials, that content was film and television programs packaged into VHS tapes and uploaded to bootleg video websites. More specifically, it was anime like Nana that gifted an aspirational Generation Y with something stylishly inspirational whenever reality disappointed our mind and closets.

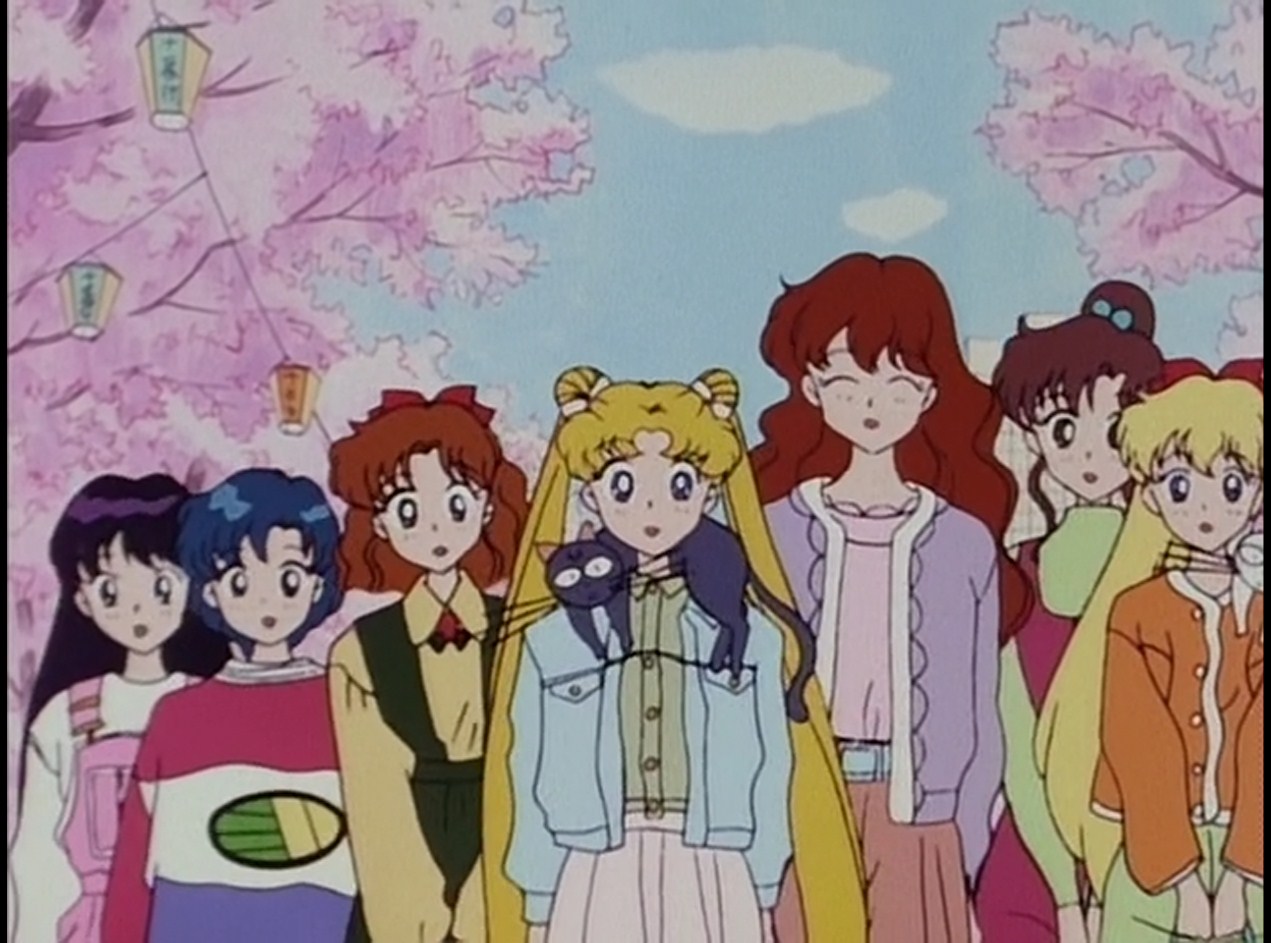

Yet, despite Nana being the most obvious instance of a fashion-centric subculture being embodied in popular anime, the most eminent works of Yazawa (like Nana and Paradise Kiss) are merely two femme-targeting instances of Japanese animation’s overt commitment to expressive personal style in its character creations. A keen eyeing of then-new anime from the heyday of millennial youth — circa the late 80s to about a half-decade ago — reveals even the most famous mainstream films and programs to be either trendsetting or trend-adopting. 30 years after its theatrical release, the dystopian classic Akira usually has a presence in conversations on cyberpunk fashion, while ruby-red leather biker ensembles are now tantamount to the disobedient, heated persona of protagonist and young biker-gang leader Shōtarō Kaneda. And perhaps most uniquely, the ever-booming Sailor Moon franchise incorporated both couture and everyday fashion in its distinct, changing designs by creator Naoko Takeuchi. Pulling directly from designers like Thierry Mugler, Chanel, and Dior, the wildly successful series — beloved by all genders — embodied high fashion, despite tween audiences likely being uninterested in the specific inspirations behind the glamorous hand-drawn looks. In contrast, the casual wardrobes of Sailor Moon characters vividly mirrored the trendy, preppy pieces that 80s and 90s teens lusted after at their local malls: colored high-rise denim paired with teeny cropped cardigans, or color-blocked varsity jackets and warm, knitted turtlenecks.

In fact, the everyday stylings of Sailor Moon are truly exemplary of the major discrepancies between Japanese animation and Western animation. The latter often reflects a bizarre fantasy world where 10-year-olds understand the complexities of left-wing social justice theories (like Huey Freeman of The Boondocks) or metal-mouthed teenage girls can intercept cell tower signals with their dental braces (like Sharon Spitz, the main character from Alicia Silverstone’s Braceface). But western series generally fail to parallel reality where it matters most for younger viewers: in the realm of wardrobes, hairstyles, or accessories that reflect self-expression. In these aspects, anime contrasts the uniformity of real-world Japan, notes LA-based writer, actress, and cosplayer Molly McIsaac, who studied abroad in the country after having been an admirer of Japanese art since childhood.

“The entire country’s approach towards fashion is different than Western culture,” McIsaac says. “They expect everyone to be uniform, like little worker bees for the greater good of the country, so people who feel ‘other’ express themselves 110 percent with fashion. This definitely bleeds into anime because it used to be considered an outlier art form, and I think the people who started creating it early paved the way for incredible fashion creativity in current anime and fashion movements.”

And though the intricacies of anime are indebted to both manga — animation’s inked, black and white precursor of an equally spectacular caliber — and Japan’s considerably duller reality, its history doesn’t negate the way anime has overshadowed western animation in the art of teaching young, creative minds how to combat homogeneity through personal style.

It’s unsurprising that today, millennials from around the globe are using social media as a platform to exchange their real-life interpretations of childhood memories. For instance, while McIsaac previously recreated her own favorite anime ensembles on now-deceased (but very missed) Polyvore, 20-year-old Eliza Elento, a student and Tumblr user from the Philippines, began re-visiting episodes of Sailor Moon when she was 18, realizing that the ensembles from the shojo series were simply animated interpretations of legitimate vintage fashions. “I originally was inspired by a blog that was called ‘Sailor Civilian,’ and I thought I could pull off those looks,” Elento explains, further noting her interest in the way her own ‘closet cosplay’ allows her to take risks and appreciate her individuality. “Anime taught me that being different is worth the risk – you get to separate yourself from the masses,” she says.

And as facets of anime have so evidently influenced millennials wardrobes, it’s not so difficult to fathom the idea that anime’s played a sizable role in various contemporary fashion landscapes; indeed, anime not only serves to inspire the way today’s youth culture looks, but is now poised as the subject itself. Evidencing luxury fashion’s infatuation with anime aesthetics was Louis Vuitton’s spring/summer 16 ready-to-wear show, which featured visuals inspired by Neon Genesis Evangelion, Ghost in the Shell and Sailor Moon. Streetwear, on the other hand — an eternally growing culture dominated by male millennials — has collectively expressed its affinity for Japanese animation via numerous collaborations with the creators of pioneering anime like Akira and Dragon Ball Z. In these instances, film stills and title card designs are slapped onto closet essentials like A Bathing Ape hoodies and Supreme tees, surely to be worn by kids who weren’t even alive when these works came to fruition. With these styles, millennial designers are, perhaps inadvertently, introducing the next generation of youth to the beautiful, nostalgic art that 80s and 90s kids were raised on and motivated by. Thus, as the charm of yesteryear’s anime made millennials fashionable, we made that anime fashion.