Reza Abdoh was one of the most radical figures in American experimental theatre, when he died of AIDS-related causes at just 32 years old. Over the course of his short-lived career, he collaged references to cable television with fairy tales, classical texts, BDSM and queer club culture to create productions that held up a mirror to the abuses of American society. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Abdoh’s maximalist productions staged throughout Los Angeles and New York boldly confronted the humanitarian crisis of the AIDS epidemic and the culture wars of the Reagan era.

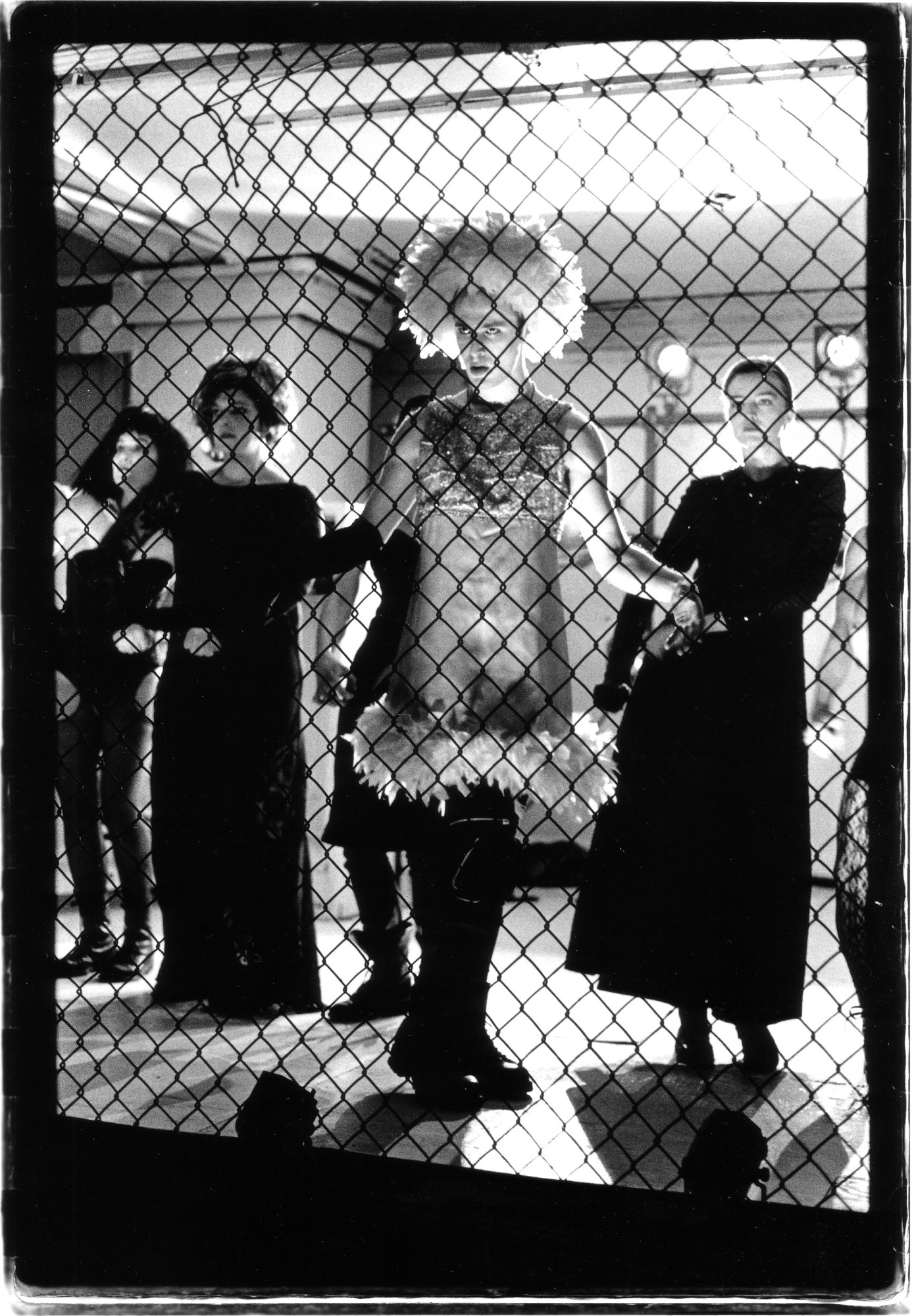

In a 1992 Theatre Review from the New York Times, Stephen Holden wrote that Abdoh’s plays seemed to want “to punish as much as to enlighten.” The playwright and director pushed both his actors and his audiences to extraordinary lengths. His plays were sometimes staged in abandoned warehouses and seedy hotel rooms; other times, on the blood-stained streets of an ungentrified Meatpacking district.

When Abdoh died, he left instructions for his work never to be performed again. Save a few videotapes of performances that circulated amongst the theatre community, his surreal productions remain largely unseen. Reza Abdoh, currently on view at MoMA PS1, is the first large-scale retrospective dedicated to the late Iranian-born artist.

The six-room exhibition begins with a timeline anchoring Abdoh’s progress from wealthy Iranian boy to cult theatrical boy wonder. Abdoh was born in Tehran during the gilded age of the Shah’s Iran. He grew up on a large estate and attended the prestigious Wellington boarding school in England, where he assisted a professor on several theatrical productions.

Following the Iranian Revolution, Abdoh’s father and three brothers were forced to look for exile in America. They settled in Los Angeles in 1979 (referred to as “Tehrangeles” for its population of Iranian exiles) and lived there illegally until Reagan’s Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) granted amnesty to immigrants in 1986. Abdoh first found out he was HIV-positive when he underwent the requisite AIDS test to apply for a green card – a fact that did much to inform his later practice.

Abdoh’s father was physically abusive and Abdoh often sought out the love and comfort of older gay men, sometimes in exchange for money. With plans to start at USC, Abdoh moved into his own place and began staging informal plays all over Los Angeles. His 1988 Peep Show guided audience members from grimy hotel room to hotel room, each containing disturbing scenarios about porn, drugs, and the Iranian Counter-revolutionaries known as the Contras. His remake of Euripides’s Medea was staged in an indoor basketball court.

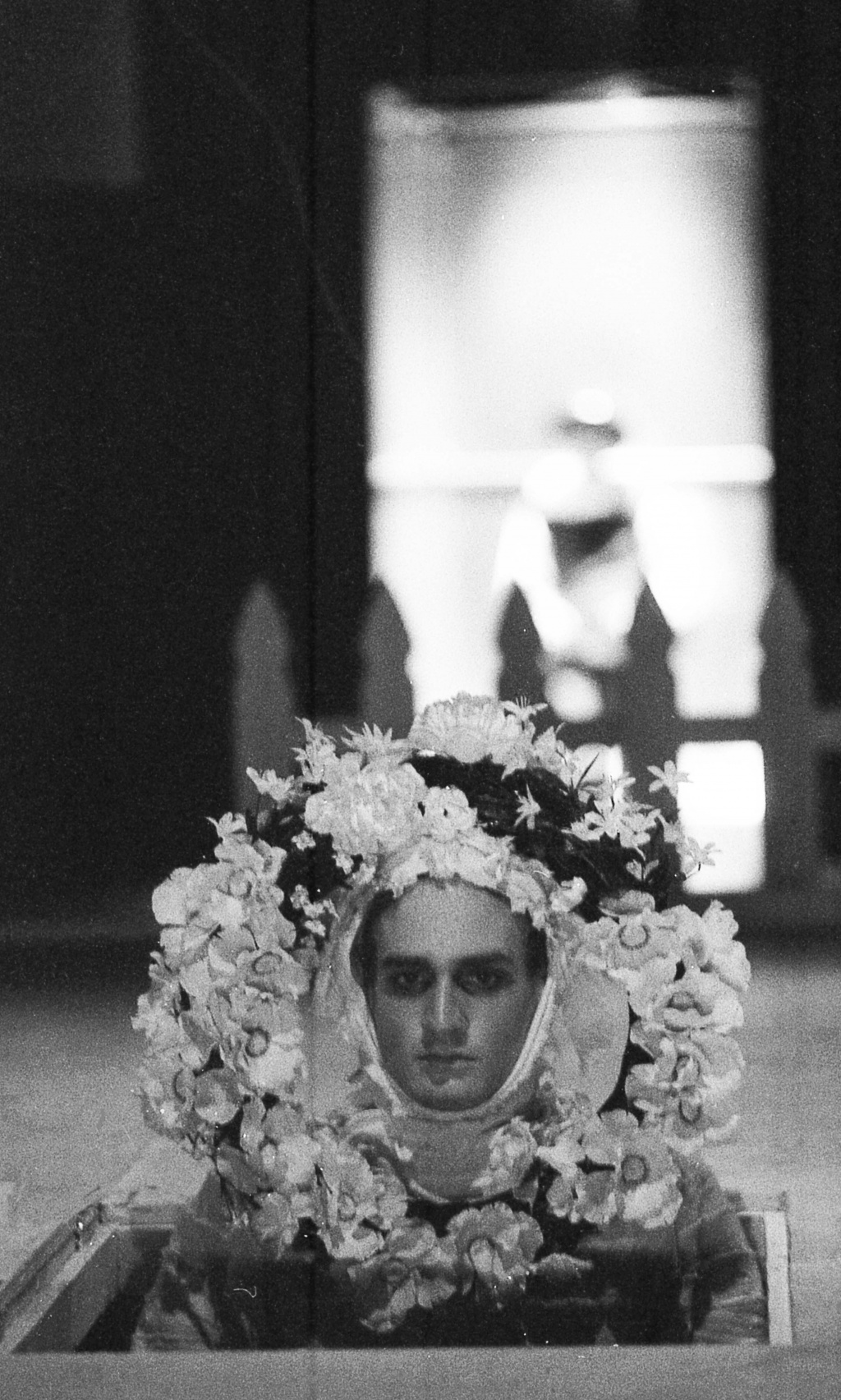

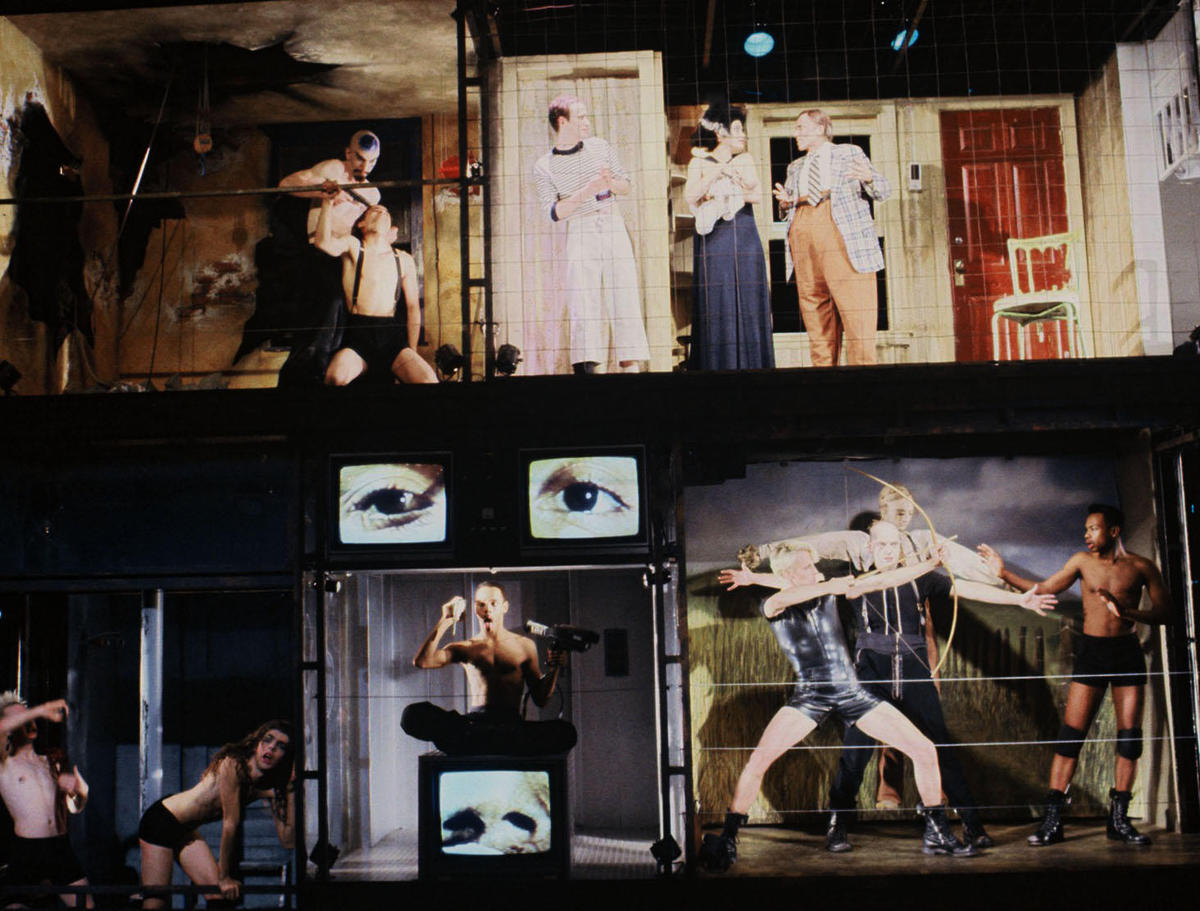

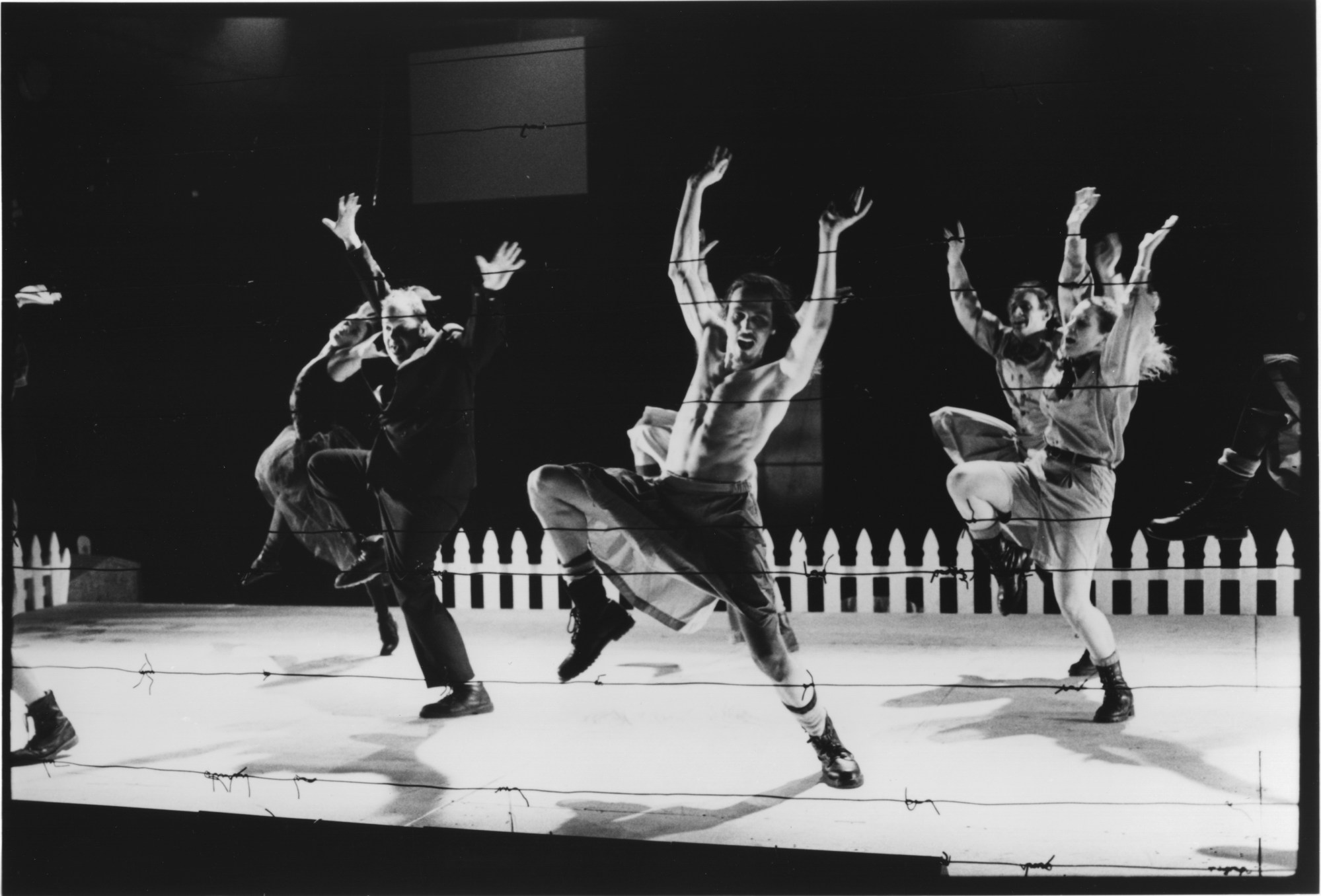

One of Abdoh’s best-known works, The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice, is projected in one of the exhibition’s three screening rooms. In the classic love tale, Orpheus tries to convince the gods of the underworld to let him bring his beautiful wife, Eurydice, back to the world of the living. Like the offshoot of a nightmare, Abdoh’s reimagining of the classic Greek myth included androgynous characters whose genders were intentionally reversed.

Abdoh was one of the first theatre artists to incorporate video in his productions. Disturbing clips of a dancing naked male body attached to the head of President Bush and an exploding Statue of Liberty formed part of the backdrop. Sylvie Drake, a theatre critic of the LA Times, warned that Hip-Hop was “not for the faint of heart.” She also described the play as “puzzling, fragmented, hard-edged and brilliant as a diamond.”

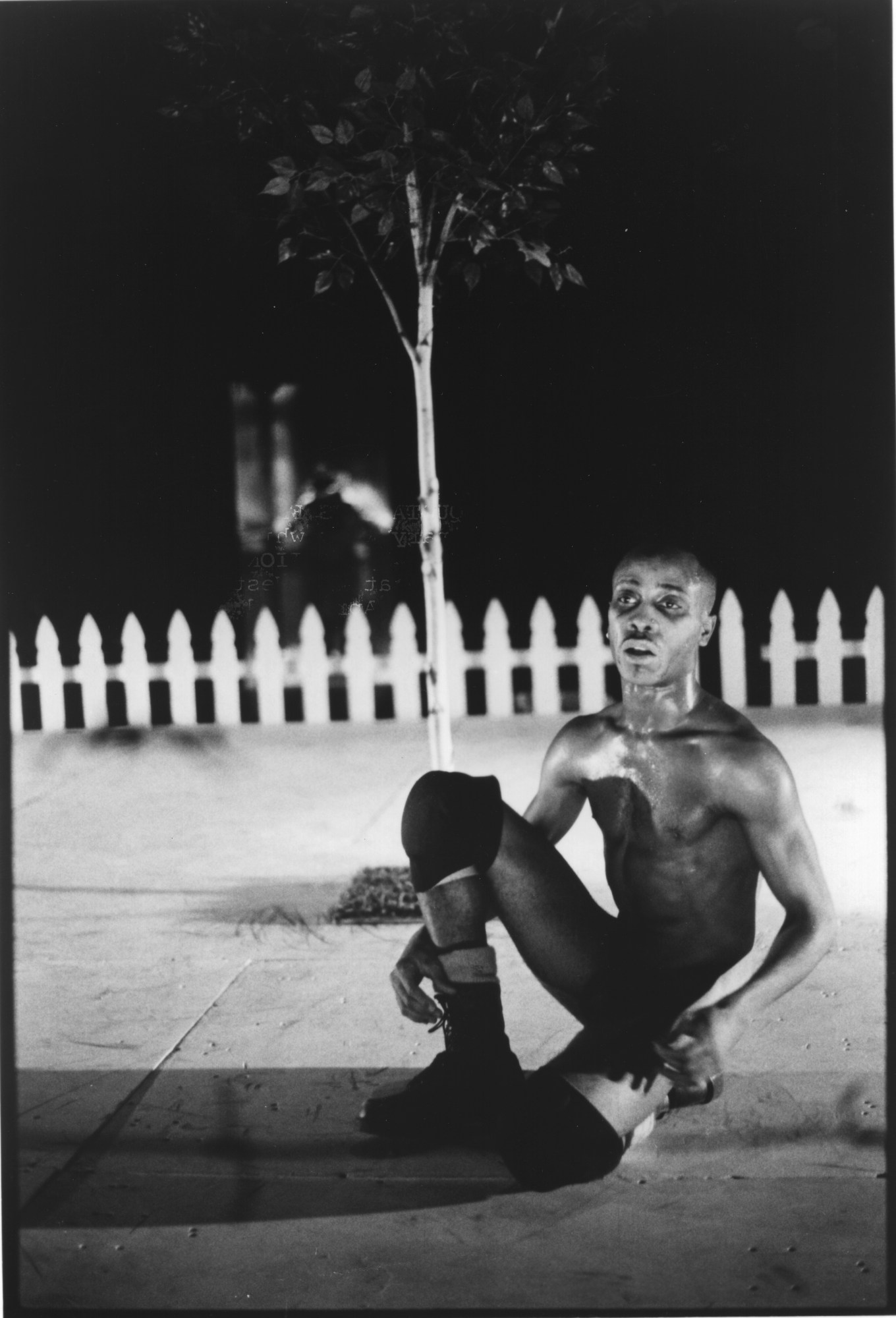

With his production company, dar a luz (purposefully lower-case), Abdoh produced seminal works like The Law of Remains, a surreal remaking of the Jeffrey Dahmer story by Andy Warhol, and Tight Right White, an unfettered meditation on urban decay and racism in America complete with Neo-Nazi and KKK imagery. Juliana Francis, who acted in six of Abdoh’s productions, says to have found working with him “tremendously liberating, though painful at times.” In Abdoh’s plays, the stage was a sacred space free from social constraints where nothing – not mass murder, sexual mutilation, necrophilia, or cannibalism – was off-limits.

Once, when asked by a reporter if he thought of his work as avant-garde, Abdoh replied: “No, what is radical is what is in the streets, what is radical is the war in Iraq.”

As his condition got worse, AIDS and the policing of queer bodies become more than just a metaphor in his work. Abdoh’s last production, Quotations From a Ruined City, held a mirror up to the destruction and social decay caused by capitalism in modern societies. Though AIDS is never explicitly named in the play, a man wearing an oxygen mask desperately grasping for breath is a recurring motif.

Abdoh died in his New York City apartment in 1995, ironically while working on a play with his brother about a terminally ill character. Until the very end of his life, theatre seemed to act as a lifeline for the artist. It couldn’t save him, but it seems to have given him a way of coping with a loss of faith in people, in the state, and, ultimately, in his own body. Even if we never again experience the collective sensory assault of watching one of Abdoh’s plays live, his retrospective still leaves viewers with the disturbing kind of peace that all good art should.

“Reza Abdoh” is on view at MoMA PS1 through September 3.