A whiff of poppers is not a typical greeting to visitors at an architecture opening. But with its plywood glory holes, dim red lights, and darkroom floor plans, the Cruising Pavilion at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale is a provocative, sexy antidote to the official programming across the lagoon. Proclaiming that “architecture is a sexual practice,” the alternative exhibit highlights the way contemporary and historic cruising practices have shaped modern cities and the queer experiences in them. Giving this taboo subject a platform at the usually stuffy biennale, the curators — Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, and Charles Teyssou — say they hope to “question the hetero-normative production of space itself.”

Just as cities are designed, built, and policed, their spatial structures are subverted and cruised. From scandal-ridden 18th century English “Molly Houses” to Jean Genet’s salacious escapades around 1930s Paris, the practice of seeking sex in public spaces is written into urban history. Public bathrooms, parking lots, and city parks have long been enlisted for the cause despite their planner’s intentions, while darkrooms and some bathhouses are designed specifically for it. While the Cruising Pavilion celebrates the architectural legacy of these spaces and the marginalized gay men who usually inhabit them, its most interesting moments contend with how those physical spaces are evolving in the age of geosocial apps like Grindr, and in response to mainstream commodification and acceptance of LGBTQ culture.

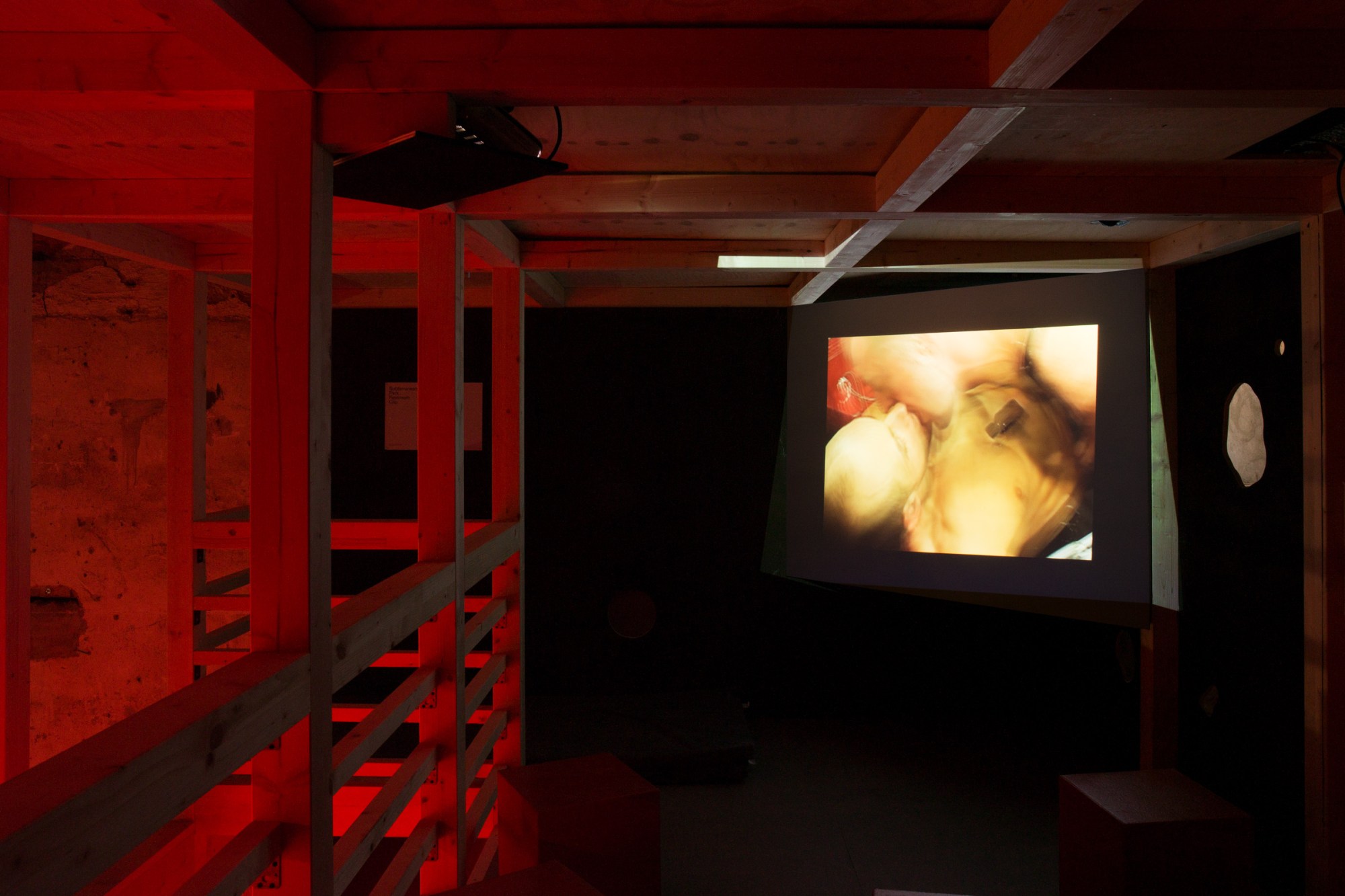

Rather than invite the mixed biennale crowd to safely consider the edgy topic of cruising on white gallery walls, the curators transformed Spazio Punch — a warehouse-like art space on Venetian Island of Giudecca — into a sort of DIY darkroom. To view the works, curious viewers must scale two dimly-lit wooden tower structures whose sharp turns and alcoves recall the labyrinthine design of contemporary darkrooms. In the cavernous industrial space between the two towers, condoms litter the concrete floor amid scarves with printed texts on “prophylaxis, sex, love, and vulnerability” from artist Lili Reynauld Dewar’s “My Contagion”. The piece “The Helping Hand” by artist Trevor Yeung spits eucalyptus oil into the air, recreating the scent gay bathhouses use in the attempt to mask smells of sex and sweat.

While the dim lights and DIY curation were admittedly disorientating, the contrast between the exhibit’s unconventional design and what I saw at the mainstream pavilions in Venice is a powerful physical manifestation of one of the curators’ central claims: cruising should be understood as a “crucial act of dissidence.” Expanding on this idea, Charles stressed how “cruising counteracts the classical agenda of clarity, order, and regulation linked to the city as it was conceptualized by the 19th century by urbanists such as Haussman or Cerdà.” While typical modern design privilege openness, mobility, and “normal” bodies/sexualities, darkrooms — and this exhibit — seek to create exactly the opposite, designing spaces that feel illicit and claustrophobic: an anti-architecture.

The curators make sure to point out to me, however, that many of the aesthetic tropes at play in the Cruising Pavilion have a specific, and recent history. Hanging in one of the wooden alcoves is an industrial light fixture from the infamous Berghain/Panorama Bar/Lab.oratory club in Berlin, in lieu of the club floorplans the curators had hoped to show. When they first got in touch with architecture firm Studio Karhard about including their designs, “they declined because there is a strict no image policy inside the club that extends to architecture plans….to ‘keep it mystic,’ as they said”. In the eyes of the curators, this made complete sense. “Their secrecy is very architectural in fact. A lot of cruising places rely on secrecy to even exist…. there is a fine line between celebrating cruising by showing it and disabling it by revealing too much of it.” In Studio Karhard’s club designs for Berghain or the Berlin gay sauna Boiler Room (whose plans are, in fact, on display), many contemporary industrial design tropes are featured — exposed concrete, pipes, factory lights or brushed metal. Interestingly, the curators see these elements as a “designed elaboration of the vernacular of gay cruising of the 70s and 80s: abandoned, neglected, industrial spaces [that] fed an aesthetic of cruising now influencing the architecture and style of gay bars, saunas and clubs”. Fittingly, the dress code poster of famed New York City BDSM club Mineshaft hangs in the entranceway to the pavilion in a clear homage to this aesthetic legacy.

While the exhibit space itself echoes the design of dedicated cruising locales, many of the works on display call attention to just how ephemeral cruising spaces can be.

The tongue-in-cheek sculpture “Cruising Labyrinth” by artist Andreas Angelidakis invites viewers to build their own “IKEA-style” darkroom maze with a piece of black-painted plywood and a glory-hole cut out. On a more serious note, Prem Sahib and Mark Blower’s photo series of the London gay bathhouse Chariots — since shuttered and replaced by luxury hotel skyscraper in toney Shoreditch — calls attention to the well-documented way gentrification eliminates many treasured queer spaces that once served as refuges for marginalized communities.

For the vast majority of people today — of all sexualities and genders — “cruising” happens over the Internet. Whether through a direct-to-sex Grindr encounter or more circuitous Tinder date, geo-social apps are radically altering the relationship between casual sex and the city. Yet, the curators are quick to observe that non-physical cruising is far from a smartphone-era invention, placing an 80s-era French Minitel machine (an early competitor to the American-developed Internet) near the entrance — a lonely reminder to cruising communication of generations past. For me, a major strength of the pavillion is exactly the way its diverse contents recall and celebrate gay men’s impressive perseverance across history co-opting both technologies and the urban environment for cruising. While nestled against strangers on an inflatable bed for Andréas Jaque’s documentary Intimate Strangers, I watched a Syrian refugee explain how Grindr had helped him connect with fellow queer refugees in his long, dangerous journey from Turkey to the Netherlands. Yet, just as police of yesteryear raided physical cruising spaces, contemporary governments block geo-social cruising networks, or worse, use these digital spaces to lure and incriminate gay men. Persistent as always, new platforms appear. Personal example: in Russia last year I was added to early-2000s-style open chat rooms in the encrypted app Telegram—a back-to-the-future cruising space in response to government repression.

While “Grindr Urbanism” can bring people together, it can also push them apart.

Asking them what they see as the pitfalls of the evolution of cruising from physical to digital realms, the curators are quick to call out how “hookup apps tend to accentuate profiling in sexual encounters by categorizing and filtering cultures, bodies, and behaviors”. Outdoor cruising spaces of the past “enjoyed a reputation of being a classless and raceless space in which social segregation had little grip,” they argue. Gay men of today can chose their “tribe,” excluding all who don’t fit their preconceived sexual and social inclinations.

So, should we mourn or celebrate “Grindr urbanism” in lieu of risky, and sexy, old-school practices? Charles deflects that choice, responding that “contemporary forms of cruising can go hand in hand with older versions.” Anyone who’s seen that unmistakable orange glow from the iPhone of the guy you just chatted up at a bar will know that truth very well.

“The Cruising Pavilion” is on view through July 1 at Spazio Punch in Venice, Italy.